Saturday, January 6, 2024

Mapping Aotearoa New Zealand’s seafloor for safer navigation

Friday, January 5, 2024

Tech standard to reshape shipping one brick at a time

The S-100 framework has been given teeth to drive maritime digitalisation

When electronic chart display and information systems, or ECDIS, became mandatory on all ships, it not only opened a technology door for the industry but paved the way for a set of standards that created fresh opportunities for businesses, including shipowners.

These standards include product specifications and extend much further than how an ECDIS will be used.

Experts believe it will bring about huge developments in maritime as data becomes machine-readable rather than focused on how it is displayed on a digital chart.

In 2022, a framework standard for these technological and communication building blocks became mandatory.

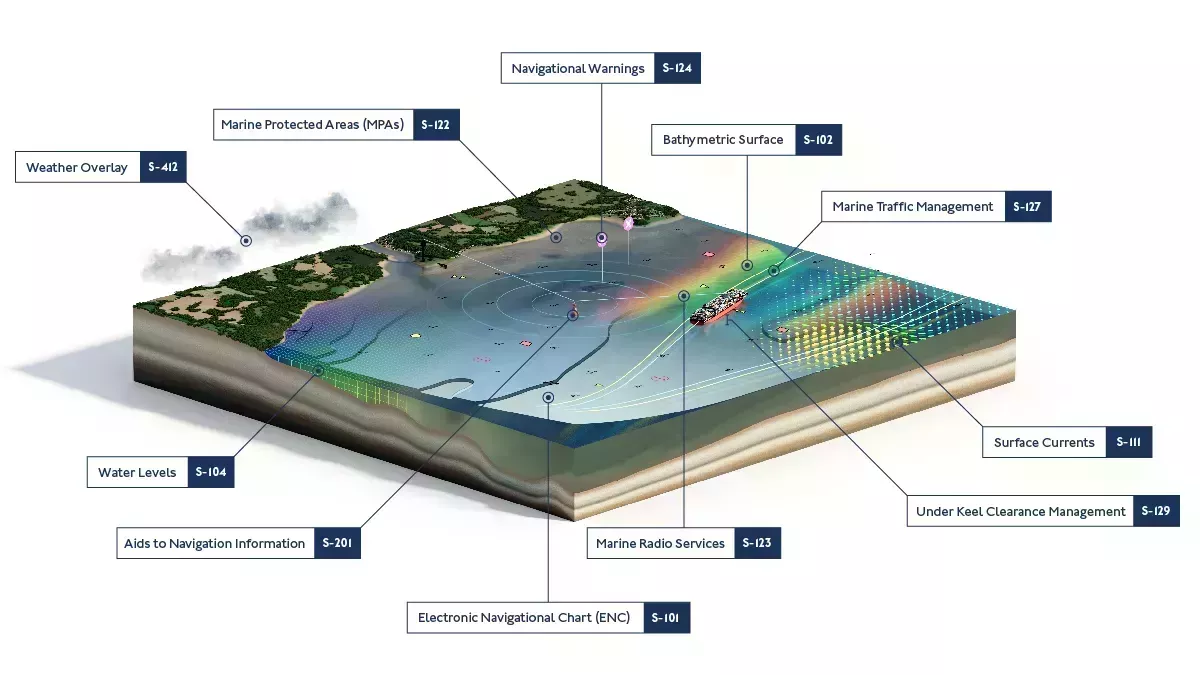

The standard S-100 was developed by the International Hydrographic Organization and includes a whole series of product specifications such as weather and route reporting, and tidal and bathymetric information.

From 1 January 2029, all new ECDIS must be built with S-100 capabilities, and manufacturers can do so voluntarily from January 2026.

S-100 is not new.

But now it is being given teeth.

Magnus Wallhagen, Sweden’s National Hydrographer and chair of the IHO Hydrographic Services and Standards Committee, likened the S-100 to a popular children’s toy.

Nick Chubb, founder and strategy director at maritime technology research consultants Thetius, said S-100 has implications across the maritime domain awareness space, and in navigational safety and voyage optimisation.

But he added that the biggest change will be in the development of autonomous systems.

A recently published report from Thetius points to a 42% year-on-year investment in digital hydrographic solutions since the S-10

S-100 comes with a range of product specifications that will become operational in the coming years, covering surface currents, tides, under keel clearance, real tide heights, aids to navigation such as lights and fairways, and route plan sharing or exchange.

The latter has now been provisionally agreed at the IMO.

The standard’s proponents say it will allow vessel traffic operators working ashore and bridge teams on ships to gain the benefits of sharing the data, and give shipping companies a common approach to do so with ports, charterers and others.

Fredrik Karlsson of the Swedish Maritime Authority, who is leading its work on route reporting, said the specifications will be a significant step in facilitating autonomous navigation as it allows machine-to-machine information exchange.

The standards will allow for route amendments to be updated automatically, and for times of arrival at specific waypoints and the end of passage to be monitored.

While ECDIS will eventually be built incorporating the S-100 framework standard, around which its functionality will be based, there will be no requirement for route exchange to be used.

Rather, the government agency in Sweden and others want to see it being so beneficial to shipowners, ports and vessel traffic service operators that its use becomes a de facto standard.

— Magnus Wallhagen

Wallhagen added that a common format for sharing routing data will help with the push for just-in-time arrival so vessels do not consume more fuel than needed.

Karlsson has worked for many years as a seafarer, in search and rescue, and in Sweden’s Vessel Traffic Services for the maritime authority.

“Navigation officers need to plan a route before the vessel leaves the quay, that’s already mandatory, even if it does not need to be shared,” he noted.

He added that if ship operators and ports begin sharing information on various timings such as arrivals at waypoints and fairways and see these benefits, they can then start sharing the routes, thus understanding the business benefits and the added security and safety.

The move towards just-in-time arrival, or smart sailing, where ports and vessels share arrival and berth availability data automatically has been a discussion topic with the industry for many years, not just because it saves fuel by allowing vessels to sail at more optimal efficient speeds, but it allows vessels to time their arrival for berth availability.

This of course reduces anchoring time and demurrage costs.

The specifications will also benefit how shipping companies can access standard weather routing and voyage optimisation information, a change that could have an impact on the optimisation market where many companies remain focused on manually compiled noon reports.

The development and mandatory rollout of S-100 into equipment may not seem an immediate benefit to shipowners other than those relating to navigation safety in an ECDIS.

Still, Chubb said the opportunities in the coming decade can be significant.

He cites the potential of the S-100 framework standard alongside the development of a newer extension of the AIS that is under development.

This is the VHF Data Exchange System (VDES).

The International Association of Lighthouse Authorities defines VDES as “a radio communication system that operates between ships, shore stations and satellites on AIS, Application Specific Messages and VHF Data Exchange frequencies in the Marine Mobile VHF band”.

Chubb said it is the tool by which S-100-compliant vessel route information can be shared, and importantly, will enable the development of autonomous systems away from ECDIS, which is a human interface tool.

Karlsson also points to another recently approved tool, an application programming interface known as SECOM, the International Electrotechnical Commission’s Secure Communication between Ship and Shore, which has been designed for S-100 information.

All of these digital standards and specifications are key enablers of the evolution of autonomous solutions in maritime, and, as Chubb also noted, a link between shipping and other marine sectors that are also able to use the same tools.

- Cruise&Ferry : Staying safe with the next generation of navigation solutions

- GeoGarage blog : s-100 / A new generation of data standards / UKHO: The next generation of navigation technology will transform shipping / New trial data sets for S-104 (Water Levels for Surface ... / After 20 years of service, AIS is about to get a big upgrade / First global VDES satellite network to launch in 2022

Thursday, January 4, 2024

Millions of Chinese are venturing to the beach for the first time

image: billy h.c.kwok

image: billy h.c.kwokFrom The Economist

Millions of Chinese are venturing to the beach for the first time

China’s beach culture is a microcosm of society

A man with a giant tattoo of a carp jumping over a dragon is making a video of himself standing in the water, a green inflatable ring around his waist.

As he films, waves move up the shore and catch the black flip-flops he has left on the sand.

He grabs at one, but the water pulls the other out of reach.

It is 7am and the competition is on, selfie versus shoe.

The sandal floats out into the South China Sea.

On the shoreline nearby, several of the man’s high-school classmates are smoking.

Two of them sport matching flowery swimming trunks that they have just bought for 45 yuan ($6).

Last week the 18-year-olds drove six hours south to Shenzhen in southern China, a stone’s throw from Hong Kong.

Fortune-hunters from all over the country have tracked a similar path since 1978, when this rural backwater led the way in powering China’s growth.

Today, however, the streets of China’s most prosperous city are no longer paved with gold.

The economy is struggling.

But the tattooed man and his blossom-shorted friends are a different kind of pioneer.

Like millions of Chinese, they are making their first trip to the edge of their country—to sample the pleasures of the beach.

Mention of China’s coast is more likely to conjure visions of warships in the South China Sea or Taiwan Strait than sandcastles.

But the population’s growing enthusiasm for being beside the seaside also points to the changing relationship between state and society in China over the past 70 years.

Tiny pockets of the country’s 18,000km shoreline were first domesticated some 150 years ago, mostly by foreign colonialists, just as European beaches were becoming destinations for pleasure rather than simply medicinal sea-bathing or “taking the air”.

In the 1950s Mao Zedong rejected traditional imperial retreats for a summer getaway with top Communist officials at Beidaihe, near Beijing, once frequented by the British.

It was from there that the Great Leap Forward was launched in 1958.

Few Chinese had jobs as portable as party bosses, however.

In the West the dawn of mass travel saw holidaymakers jetting off to sunny shores at a time when most Chinese were tied to the land or factory.

Leaving the city became a punishment for intellectuals in the 1960s, not a sightseeing experience.

Even after restrictions on movement eased in the 1980s, urbanites typically used their one annual holiday to return home.

Since then domestic tourism has taken off, boosted by speedy transport links and rising disposable incomes.

China’s beach culture was turbocharged by the pandemic, when socialising outdoors became desirable and those accustomed to overseas travel were forced to pursue their foreign-holiday practices at home.

Even the party seemed to approve.

When “Born to Fly”, China’s answer to “Top Gun”, was released in April 2023, it portrayed the fighter-pilot hero as a steely daredevil.

The evidence? His love of surfing.

The little white look

Yi Wangxia—her name means sunset—came to the beach to feel the “force of nature”.

The landscape is beautiful at Dameisha, “big plum sand”, says the 26-year-old, then leaps back as the water looms at her crisp white dress.

She recently passed a basic swimming test for her maritime-management course but is afraid to go in the ocean.

Nor will communing with nature involve eating seafood.

Chinese officials have stoked fears about contaminated fish since August, when Japan began releasing treated wastewater from the nuclear plant destroyed by a tsunami 12 years ago.

Those who do brave the water face little danger.

Mao swam the Yangzi river in 1966 to demonstrate his physical and political prowess as he launched the Cultural Revolution.

Decades on, however, the Chinese remain largely a nation of non-swimmers.

Apart from a dedicated troupe of dawn swimmers, most who venture into the sea at Dameisha wear inflatable rings—even the adults—and stay in the shallows.

A lifeguard smokes or shouts into a megaphone, less to save lives than to enforce the boundaries of a narrow rectangle of the water given over to swimming.

Even more glaring is the absence of figure-hugging swimming costumes ubiquitous in the West.

Some women wear suits with sleeves and skirts or long shorts.

Others sport swimming dresses with reinforced bodices and knee-length skirts.

A few enter the water fully clothed.

In four days, only one Chinese woman was observed in a regular swimsuit—bright pink with frills—which she had bought for her first beach holiday in 2021.

Wives of Communist leaders at Beidaihe sometimes wore Western-style swimsuits.

(Mao and Deng Xiaoping, his successor, were both photographed in trunks but Xi Jinping, China’s leader, eschews bare-chested beach shots.)

Why, then, the lack of swimsuits or bikinis today?

“Being dark makes you look ugly and old,” says a 57-year-old Beijinger who wears her cap low and an spf face-covering across her cheeks.

To many people pale skin is also a proxy for class, distinguishing toiling farmers from city-types who think their office work and service jobs make them refined.

(Europeans held a similar view until the 1920s when a tan became a sign of having leisure time.) Beachside shops cater to such fears, selling cotton sheaths to pull over bare arms, umbrellas for shade, covid masks repurposed as face protectors, and “facekinis”—swimming masks that reveal only the eyes, nose and mouth.

No swimming and no sunbathing.

Few picnics; despite an outbreak of “picnic fever” during the pandemic, most mealtime food in China is hot.

Little booze and even less canoodling.

Sure, some children dig holes and paddle.

But at Dameisha a beach-volleyball net and giant swing are largely unused.

So why does anyone bother to visit the seaside at all?

Self-portrait of beachgoer as a young man

Self-portrait of beachgoer as a young manMs Li’s antics provide a clue.

She and her boyfriend of two years are not at Dameisha to swim (they cannot) or eat oysters (radiation).

They wanted to go to the sea because their native Lanzhou in western China is so dry.

But mainly because the beach is the perfect spot for photographs.

In a cream mesh dress and floaty veil Ms Li looks as though she is posing for her wedding photos.

In fact, she and many others are dressed for the beach: the shoreline is one long photo shoot.

Four women have set up a tripod to snap selfies, two in flowing red dresses, two in qifu, a form of Chinese dress, with right arms raised to look as if they are holding up the sea.

A woman in her 20s had travelled several hours that morning wearing a purple wig and purple mouse ears to take photos holding an illuminated star with fairy lights draped around her short purple dungarees.

In the 1990s, when few Chinese had their own cameras, photographers with instant cameras would snap visitors at tourist sites.

People wanted images not merely of an attraction or landscape, but of themselves in front of the setting.

Those rare, precious Polaroids were the forerunners to the smartphone selfies posted online today; both are proof of an individual’s experience.

And a new destination must be celebrated with a special outfit.

One woman (dressed in ordinary clothes) has brought her cat, Luna, trussed up in a peaked cap with holes for her ears and a lilac bodysuit.

For centuries China’s imperial rulers viewed the country’s shorelines as a buffer against a barbarian world.

At times they forbade people from living within 15-25km of it.

Today the sands at Dameisha are dominated by giant winged sculptures, commissioned by the city government.

Impressive facilities serve the day-tripper—large toilet blocks (which even boast soap, rare in Chinese bathrooms) and showers; the metro will soon connect the seaside to urban Shenzhen.

Look closer, however, and the party’s presence is more insidious.

Day-trippers are not the only ones taking photos.

Entry gates capture an image of everyone who enters the beach; no state has more sophisticated face-recognition software than China.

Tall towers stand every 120m up the beach with surveillance cameras pointing in all directions.

Rather than encourage citizens to trust one another, a sign by a giant shoe rack reminds visitors that the cameras are watching.

images: billy h.c. kwok

images: billy h.c. kwokIn many ways this surveilled sandy fringe embodies the social contract that the Communist Party made with the Chinese people after the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989: political loyalty in return for greater personal freedom and affluence.

Anyone is free to come to the Chinese seaside, from the spotty 16-year-olds who dropped out of vocational college to the son of a tech worker who dashes in and out of the water, a giant grin revealing a gap where his front tooth came out at lunchtime while eating a spicy snack.

(Or almost anyone—next to the free public beach is a private one, plus yacht club: “Shenzhen has many bosses,” says a staff member.)

The beach party

Even under the party’s watchful gaze, there are signs that the social contract is beginning to fray.

Political loyalty is no longer guaranteed.

Few people mention Mr Xi’s name at the seaside but his policies are ripe for discussion.

A construction worker came for a dip because he can no longer find work now the property sector is floundering.

A 20-something is feeling the pain of urban youth unemployment: he sells fingers of bright pink, processed sausage for three yuan apiece, cooked on a hotplate mounted on his three-wheeled bicycle.

Often he makes just 100 yuan a day.

A beach cleaner abandoned life as a subsistence farmer four years ago and now works seven days a week, living in a dorm for 300 yuan a month, aged 50.

“It’s tough, but what can you do?”Not everyone is getting richer or thinks that life is getting better

Not everyone is getting richer or thinks that life is getting better.

People still bemoan the long lockdowns in the late days of the government’s “zero-covid” policy.

A woman whose tutoring firm had to shut when the government banned extra-curricular classes in 2021 is now applying for postgraduate degrees in Hong Kong—she wants a “better education” for her five-year-old.

(Her husband, also a tutor, is trying his luck as an influencer-come-English teacher on Douyin, China’s TikTok.) A government worker from Inner Mongolia had to hand in her passport during the pandemic, as did most state employees, and must now apply to the authorities if she wants to go abroad.

As the light dims after 5pm, the state comes to the rescue again: bright floodlights flash on, extending the day’s joy.

Even when it is wholly dark, children build castles and race toy diggers.

A couple walks in the water, shin deep.

A family unfolds a table and chairs to eat a kfc dinner.

The social contract is safe—for now.

And more brave folk step out into the South China Sea.

Wednesday, January 3, 2024

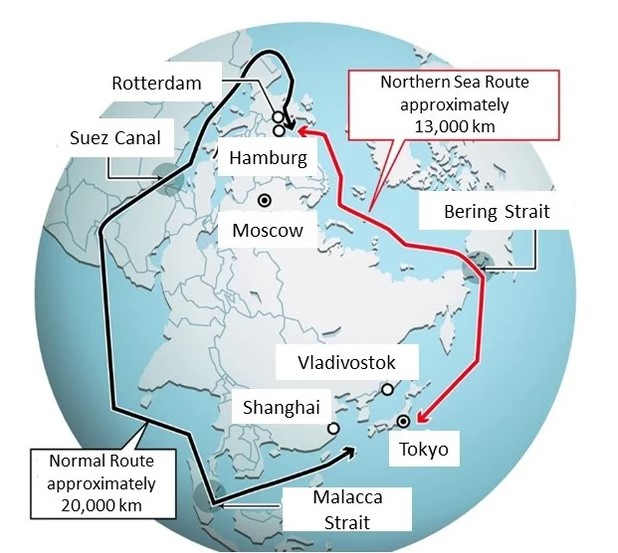

Northern Sea Route saw seven containership voyages in 2023, including controversial trip by Chinese container ship

From HighNorthNews by Malte Humpert

Northern Sea Route shipping activity during the summer of 2023 included the first regular container service between Asia and Europe.

After years of announcing grand, but hitherto unfulfilled plans by Russian officials for routine container traffic on the Northern Sea Route (NSR), the Arctic seaway saw the first significant regular liner service this summer.

China’s NewNew Shipping Line dispatched four container ships along the route between July and November, completing a total of seven voyages.

NewNew Shipping Line provided service between ports in East Asia and St Petersburg, with some vessels making intermediate stops in Arkhangelsk and ports in the Baltic Sea.

All four container ships, NewNew Polar Bear, Xin Xin Hai 1, Xin Xin Tian 1, and Xin Xin Shan, feature light to medium ice protection between class Ice 1 and Arc 5 and are able to carry between 1,200 and 2,800 standard containers.

In comparison, the world’s largest container vessels transport in excess of 20,000.

NewNew Polar Bear managed to complete three full transits of the NSR, a unique feat for a containership on the route.

It completed another late-season eastbound voyage, with a stop in Arkhangelsk, arriving in China in early December.

Additional voyages were conducted by Xin Xin Hai 1, which completed a three month trip between Busan and St Petersburg and returned to the Russian port of Vanino.

Both vessels returned to Asia via the Suez Canal.

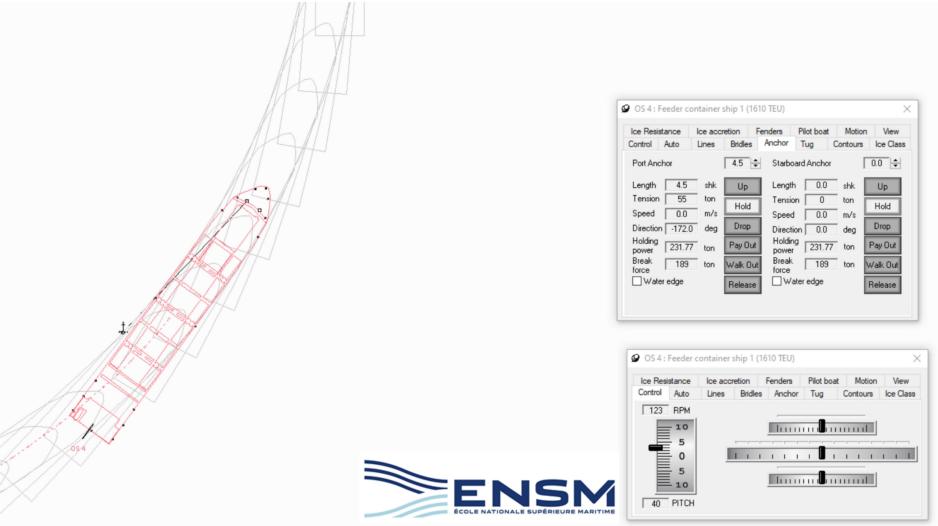

Incident remains unresolved

Apart from the novelty of Arctic container operations, the company’s NewNew Polar Bear garnered international attention when the vessel appears to have damaged subsea infrastructure in the Gulf of Finland.

According to Finnish officials, the ship dragged and subsequently lost its anchor along the seafloor for 180 km damaging the Balticconnector natural gas pipeline.

Shipping experts, who ran simulations about the loads involved when dragging an anchor and the likely course divergences, question the accident theory.

“The hypothesis that it lost its anchor and dragged it on the bottom for a very long distance does not seem very credible,” explains Hervé Baudu, Chief Professor of Maritime Education at the French Maritime Academy (ENSM).

“The accidental theory of an anchor line dragging for several miles without the ship realizing it is unlikely,” continues Baudu.

NewNew Polar Bear also conducted a two-day stop in a remote fjord in Russia’s Kamchatka, which raised eyebrows among shipping experts.

“Also strange are the two anchorages that the ship made at the end of the return transit on the NSR, one on the Kamchatka peninsula and the other to the south of Sakhalin Island. Could it then have picked up a new anchor?” questions Baudu.

Much speculation continues to surround the incident and officials, including from the Finnish National Bureau of Investigation, requested the vessel’s inspection upon its return to China.

“It is easy to check, because the anchor line and the anchor have a nomenclature number to track the condition of the equipment. So, was there any intention to rupture the pipeline or was it pure coincidence? Only a thorough inspection by the Chinese authorities will quickly clear up any doubts,” concludes Baudu.

- HighNorthNews : China Pushes Northern Sea Route Transit Cargo to New Record / Gazprom Sends First-Ever Shipment of Baltic LNG to China via the Arctic / Northern Sea Route Sees Lots of Russian Traffic, But No International Transits in 2022

- The Diplomat : Arctic Ambitions: China’s Engagement With the Northern Sea Route

- The Maritime Executive : Russia Claims New Record for Cargo on the Northern Sea Route

- The Moscow Times : Russia Ramps Up Arctic Route Ambitions

- Splash : Milestones reached along the increasingly busy Northern Sea Route

- Bloomberg : Russia’s Arctic Shipping Route Gets Busy With Oil Traffic to China

- GeoGarage blog : A pipeline mystery has a $53 Million solution

Tuesday, January 2, 2024

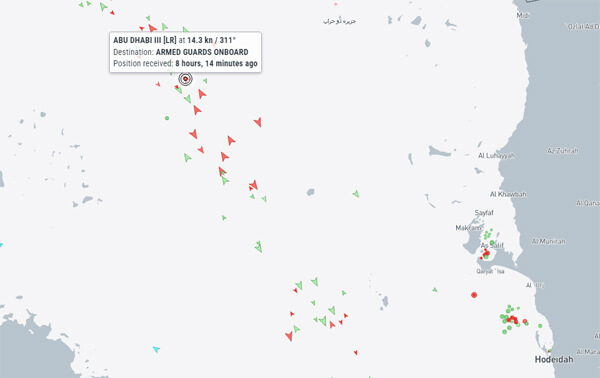

Iran-Houthis tap AIS tracking tech for high sea attacks

Ships transiting the Red Sea are sending out messages to ward off attacks

Ships transiting the Red Sea are sending out messages to ward off attacksMany ships have chosen to reroute away from the danger while it also appears some are trying to use a novel means of communication to speak indirectly to the Houthis to ward off potential attacks. Since launching the attacks, the Houthi rebels in Yemen have vowed to target any ships owned by Israeli interests or trading with Israel.

The Houthis appear to be

using the Internet and searching databases to identify at least some of

their targets.

Initially after the seizure of the car carrier Galaxy Leader,

and with reports of small boats attempting to hail or board ships, the

owner/operators responded by increasing onboard security.

There were

several reports of armed guards firing warning shots at small boats when

they came too close.

Normally the vessel’s Automatic Identification System is used to post

information about the ship’s destination, direction, and speed.

Occasionally it is used to warn of dangers.

It is common to see a ship

listed as “not under command,” when it is experiencing a mechanical

problem to warn ships not to approach.

A vessel between contracts often

posts a message “awaiting orders” to say it is anchored or drifting

aimlessly.

Now, however, ships have started using their AIS to communicate indirectly with the rebels.

When the primary fear was boardings, ships began displaying messages saying “armed guard onboard.” Several tankers transiting the Red Sea today are showing that message as their destination. TankerTrackers.com highlights in its posting on X (formerly Twitter) that it identified a new message attempting to say we are not involved in your fight.

The tracking and analytics company detected several vessels using a new tactic, posting a message they called “interesting.”

In hopes of not being targeted by Houthi militants, a Greek-owned tanker that departed Russia is currently broadcasting over AIS that it has nothing to do with Israel. pic.twitter.com/iY4ixCuMgW— TankerTrackers.com, Inc. (@TankerTrackers) December 28, 2023

PS: Two other vessels, container ships at that; are stating the same thing as well. Both began their voyages in Russia, too. Interesting. pic.twitter.com/Y7rQi9h9aG— TankerTrackers.com, Inc. (@TankerTrackers) December 28, 2023

TankerTrackers.com posted an image to X showing the tanker displaying the message “VSL No Cntact Israel.”

The 46,350 dwt/3429 TEU containership owned and managed out of China is also outbound from Novorossiysk, Russia, but a decade ago appears to have operated under charter to the Israeli shipping company Zim.

TankerTrackers.com reports it also spotted a third vessel displaying the same message earlier today. It is not clear if the message is reaching the intended target and if this is a coincidence or a planned effort to try and ward off attacks.

Earlier this week, the destroyer USS Laboon took down 12 one-way attack drones, three anti-ship ballistic missiles, and two land attack cruise missiles in 10 hours, all fired by the Houthis in the Southern Red Sea.

On Thursday, USS Mason shot down one drone and one ballistic missile, according to U.S. Central Command.

Monday, January 1, 2024

Obibini

For most of their history, Ghanaian beaches were reserved solely for working men due to a prevailing fear of drowning in the village.

In 2017, a man named Justice Kwofie spearheaded a transformative movement along with his six brothers with the establishment of the Obibini Surf Club.

Justice's visionary stance ushered in a wave of change along Ghanaian beaches, liberating women from historical limitations and sparking enthusiasm for the sport.

Sunday, December 31, 2023

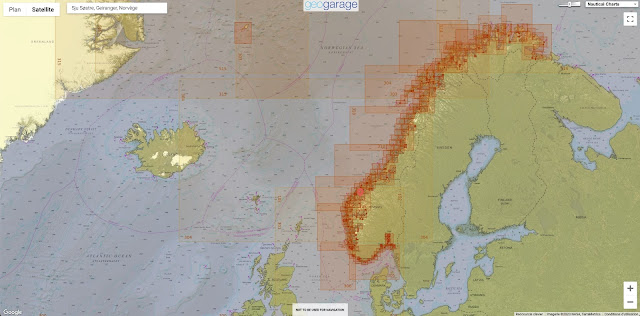

Norway (NHS) layer update in the GeoGarage platform

We went to the biggest iceberg in the world on RRS Sir David Attenborough | British Antarctic Survey

View of A23a from the deck of RRS Sir David Attenborough (Rich Turner)

View of A23a from the deck of RRS Sir David Attenborough (Rich Turner) Orca in from of A23a (Liam O’Brien)

Orca in from of A23a (Liam O’Brien) Edge of A23a, 1 December 2023 (Theresa Gossman, Matthew Gascoyne, Christopher Grey)

Edge of A23a, 1 December 2023 (Theresa Gossman, Matthew Gascoyne, Christopher Grey)“Calving of icebergs from Antarctica’s ice shelves is part of the natural life cycle of glaciers. Polar ecosystems play a crucial role in regulating the balance of carbon and nutrients in the world’s oceans and are impacted by melting icebergs in numerous ways. The data being collected will improve our understanding of these processes and their sensitivity to climate change.”

- GeoGarage blog : A23a: World's biggest iceberg on the move after 30 years

-940-420-p-L-100.jpg)