Saturday, January 18, 2025

Friday, January 17, 2025

The South China Sea comes to a boil

Chinese Coast Guard ships fire water cannons at Unaizah May 4, a Philippine Navy chartered vessel, conducting a routine resupply mission to troops stationed at Second Thomas Shoal, on March 5, 2024, in the South China Sea.

Chinese Coast Guard ships fire water cannons at Unaizah May 4, a Philippine Navy chartered vessel, conducting a routine resupply mission to troops stationed at Second Thomas Shoal, on March 5, 2024, in the South China Sea.(Photo by Ezra Acayan/Getty Images)

From The Dispatch By Raymond Powell

Why now, what are America’s interests, and what are Trump’s options?

Over the past two years, an increasingly confident and belligerent China has thrust its South China Sea aggression into overdrive, fixating on the Philippines as its primary target.

Manila now faces what amounts to a large-scale maritime occupation of its internationally recognized exclusive economic zone by a hostile imperial power.

China has repeatedly swarmed, blocked, and rammed Philippine ships while also deploying nonlethal but dangerous weapons such as lasers, water cannons, and long-range acoustic devices in a brazen attempt to stamp out Manila’s spirited resistance.

While China has become more obviously belligerent over the past two years, the roots of its ambition date back more than a century.

China has repeatedly swarmed, blocked, and rammed Philippine ships while also deploying nonlethal but dangerous weapons such as lasers, water cannons, and long-range acoustic devices in a brazen attempt to stamp out Manila’s spirited resistance.

While China has become more obviously belligerent over the past two years, the roots of its ambition date back more than a century.

- click on the image to magnify -

Chinese maritime capabilities have improved to the point that pushing the U.S. out of the strategically important “first island chain”—the strategic line of islands stretching from the Japanese archipelago through Taiwan, the Philippines, and Borneo, serving as a natural barrier between the East Asian mainland and the Pacific Ocean—is no longer just the fever dream of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) blowhards, but an ominously plausible outcome.

Why is this coming to a head now and what can an incoming Trump administration do about it?

Why is this coming to a head now and what can an incoming Trump administration do about it?

“Manila now faces what amounts to a large-scale maritime occupation of its internationally recognized exclusive economic zone by a hostile imperial power [China].”

Obscure maps and excessive claims.

Beijing’s claim to nearly all of the South China Sea extends back to the 1930s, when its official cartographers drew ambitious maps purporting to represent the Middle Kingdom’s broad conception of its “territory.”

Because China had few seagoing vessels at the time, these maps relied on old British nautical charts and a national mythology that postulated a once-great maritime superpower.

Its incredible claim—which would evolve into what became the infamous nine-dash line encompassing nearly the entire South China Sea—was so factually specious that its southernmost point was drawn around the completely submerged James Shoal, which at 22 meters below the surface would earn no territorial rights whatsoever under the 1983 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) treaty.

Even so, these audacious maps went largely unnoticed outside of China, as the country possessed no capability to project maritime power beyond its borders.

Its incredible claim—which would evolve into what became the infamous nine-dash line encompassing nearly the entire South China Sea—was so factually specious that its southernmost point was drawn around the completely submerged James Shoal, which at 22 meters below the surface would earn no territorial rights whatsoever under the 1983 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) treaty.

Even so, these audacious maps went largely unnoticed outside of China, as the country possessed no capability to project maritime power beyond its borders.

For the few who paid attention, the claim was treated as bizarre and almost laughable.

Nobody’s laughing now.

Nobody’s laughing now.

The reef-grab years.

The first real indication that China was preparing to lean harder into its claims came in 1974 when it staged a brief and opportunistic naval battle to evict South Vietnam from the Paracel Island group. China was still a weak naval power, but South Vietnam’s collapsing regime was an easy mark. -America, eager to extract itself from an unpopular war while courting Beijing’s realignment against the Soviet Union, had no appetite for this fight.

The Paracels fell with barely a whimper.

As suggestions of oil and gas deposits beneath the seabed began to proliferate, China turned its attention even further south, joining its neighbors in a chaotic reef-grab across the larger Spratly Island group that would extend through the end of the next decade.

As suggestions of oil and gas deposits beneath the seabed began to proliferate, China turned its attention even further south, joining its neighbors in a chaotic reef-grab across the larger Spratly Island group that would extend through the end of the next decade.

With six different countries claiming some part of the archipelago, the potential for conflict escalated until a 1988 dispute over Johnson South Reef ended in the massacre of 64 Vietnamese soldiers in a short and lopsided battle with the PLA Navy.

After this, the contest over South China Sea “features”—the various islands, reefs, and shoals of uneven legal status—subsided for a time, as all parties seemed content to assert their claims in less bloody fashion.

While China gradually expanded its naval capabilities, however, it found innovative ways to press its expansionist agenda by exploiting the “gray zone”—that murky space short of war where an aggressor seizes the advantage over its adversaries while avoiding the costs of its aggression.

Opacity and deniability are the coin of the gray-zone realm, as they paralyze the adherents to the U.S.-championed “international rules-based order” by sowing uncertainty and discord among its risk-averse, consensus-seeking rules followers.

Such was the case for China’s next big move—its 1994 placement of “fishing shelters” upon Mischief Reef, which went unnoticed for months.

After this, the contest over South China Sea “features”—the various islands, reefs, and shoals of uneven legal status—subsided for a time, as all parties seemed content to assert their claims in less bloody fashion.

While China gradually expanded its naval capabilities, however, it found innovative ways to press its expansionist agenda by exploiting the “gray zone”—that murky space short of war where an aggressor seizes the advantage over its adversaries while avoiding the costs of its aggression.

Opacity and deniability are the coin of the gray-zone realm, as they paralyze the adherents to the U.S.-championed “international rules-based order” by sowing uncertainty and discord among its risk-averse, consensus-seeking rules followers.

Such was the case for China’s next big move—its 1994 placement of “fishing shelters” upon Mischief Reef, which went unnoticed for months.

The UNCLOS treaty defines a country’s exclusive economic zone as extending 200 nautical miles from its shores, and Mischief Reef is a little more than 150 nautical miles from the Philippines. It was the first time a claimant country had put structures in another’s exclusive economic zone.

Caught off guard, the Philippines’ only available counter was to run a U.S.-donated World War II-era Navy ship, the BRP Sierra Madre, aground at nearby Second Thomas Shoal in 1999.

Caught off guard, the Philippines’ only available counter was to run a U.S.-donated World War II-era Navy ship, the BRP Sierra Madre, aground at nearby Second Thomas Shoal in 1999.

As we will see below, this makeshift military outpost would become a key flashpoint in the years to come.

Having recently abandoned its huge Philippine military bases following years of contentious negotiations with its former colony, the U.S. did little in response.

Having recently abandoned its huge Philippine military bases following years of contentious negotiations with its former colony, the U.S. did little in response.

A few fishing shelters on lonely reefs hardly seemed worth the price of aggravating an emerging economic partner with a billion potential consumers on the verge of World Trade Organization integration.

The only remaining check on China’s aggression remained its self-perception that it was not yet ready to directly challenge U.S. primacy.

The only remaining check on China’s aggression remained its self-perception that it was not yet ready to directly challenge U.S. primacy.

This reticence found voice in Deng Xiaoping’s “24-character strategy,” which cautioned: “Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.”

The end of ‘hide and bide.’

This restrained approach largely prevailed until early last decade, with the rise of Xi Jinping. That was also when a dispute over fishing rights set off a flurry of events that would reset the South China Sea board in Beijing’s favor.

China’s 2012 seizure of Scarborough Shoal, which lies just 150 miles from Manila, was unexpected, highly consequential—and a loss the Philippines could not ignore.

The end of ‘hide and bide.’

This restrained approach largely prevailed until early last decade, with the rise of Xi Jinping. That was also when a dispute over fishing rights set off a flurry of events that would reset the South China Sea board in Beijing’s favor.

China’s 2012 seizure of Scarborough Shoal, which lies just 150 miles from Manila, was unexpected, highly consequential—and a loss the Philippines could not ignore.

A fascinating 1980 infographic Petroleum News map of the South China Sea, Southeast Asia, and the East Indies, illustrating the region's rich oil and gas deposits - currently an international flashpoint between China and other regional powers, including the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei.

A Closer Look Centered on the South China Sea, coverage embraces Southeast Asia and the East Indies, extending from the Andaman Islands to the Philippines and from Hainan to Timor.

- click on the image to magnify -

The shoal is vital to the economic livelihood of its northern fishing communities.

When the U.S. attempted to negotiate a fair settlement only to get played by Beijing, an aggrieved and embittered Philippine government turned to the UNCLOS treaty and international law for a solution. President Benigno Aquino’s administration filed the meticulously researched Philippines v. China case at the Hague in 2013, taking aim not only at Scarborough Shoal but at Beijing’s entire South China Sea claim.

Having neither the facts nor the law on its side, China elected to reject the proceedings as “null and void.”

When the U.S. attempted to negotiate a fair settlement only to get played by Beijing, an aggrieved and embittered Philippine government turned to the UNCLOS treaty and international law for a solution. President Benigno Aquino’s administration filed the meticulously researched Philippines v. China case at the Hague in 2013, taking aim not only at Scarborough Shoal but at Beijing’s entire South China Sea claim.

Having neither the facts nor the law on its side, China elected to reject the proceedings as “null and void.”

Instead, it reasserted its position that “historic rights” give it “indisputable sovereignty” over all its South China Sea claims, and are thus beyond the reach of UNCLOS and its tribunals.

While Manila was busy with lawfare, Beijing decided to change the facts on the ground.

While Manila was busy with lawfare, Beijing decided to change the facts on the ground.

It deployed scores of dredgers and engineers into the Spratlys to pile 4,600 acres of sand, coral, and rock atop of its occupied coral reefs, completely transforming its small outposts into large artificial islands hosting military strongholds.

By 2016, even as Manila celebrated a sweeping legal victory in Philippines v. China (though in muted fashion due to the pro-China President Rodrigo Duterte’s untimely ascent to power), Beijing had already tipped the hard-power balance.

By 2016, even as Manila celebrated a sweeping legal victory in Philippines v. China (though in muted fashion due to the pro-China President Rodrigo Duterte’s untimely ascent to power), Beijing had already tipped the hard-power balance.

Its three new naval and air bases at Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, and (adding injury to Philippine insult) Mischief Reef underscored the new reality.

While some U.S. military planners initially dismissed these bases as easy targets in any hot war, they are highly effective as power-projection platforms for China’s gray-zone operations.

While some U.S. military planners initially dismissed these bases as easy targets in any hot war, they are highly effective as power-projection platforms for China’s gray-zone operations.

This campaign has included developing a huge paramilitary force—centered around a huge, purpose-built coast guard and shadowy maritime militia.

It now forward-stages these forces at these bases to overwhelm smaller adversaries, occupy ever-larger spans of ocean and control access to key features, all while taking advantage of their gray-zone, non-military veneer as “law enforcement” or “fishing” vessels, respectively.

While Duterte intentionally downplayed the West Philippine Sea security dilemma in exchange for promises of economic inducements, Beijing took full advantage and consolidated its position.

While Duterte intentionally downplayed the West Philippine Sea security dilemma in exchange for promises of economic inducements, Beijing took full advantage and consolidated its position.

By the time he was succeeded by Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos in 2022, Manila’s practical options were far more limited.

Maritime occupation.

Marcos proved willing to push back, however, and this renewed Philippine feistiness has brought us to the most recent cycle of escalation.

Maritime occupation.

Marcos proved willing to push back, however, and this renewed Philippine feistiness has brought us to the most recent cycle of escalation.

Beginning in early 2023 Manila adopted a novel new strategy—the first significant counter gray-zone innovation since its arbitration case.

This remarkable tactic of assertive transparency, led by the small but plucky Philippine Coast Guard and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, adopted a seek-and-photograph approach that broadcast Beijing’s mendacity in vivid color for all to see.

This remarkable tactic of assertive transparency, led by the small but plucky Philippine Coast Guard and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, adopted a seek-and-photograph approach that broadcast Beijing’s mendacity in vivid color for all to see.

The Philippine media, kept in the dark for six years under Duterte’s policy, leapt at the chance to come along and embed on their patrols.

Initially staggered by this new approach, China reacted by dispersing its forces to make them harder to catch on camera, while trying to coax and coerce Marcos back on side.

Initially staggered by this new approach, China reacted by dispersing its forces to make them harder to catch on camera, while trying to coax and coerce Marcos back on side.

By summer 2023, however, Beijing changed tack. It pushed even more ships down to Mischief Reef and dug in for the Battle of the West Philippine Sea, Gray-Zone Edition.

Made-for-TV blockade running.

That brings us back to the beleaguered BRP Sierra Madre.

In the quarter-century since its grounding, little had been done to shore up the ship, to the extent that many wondered whether the next large storm might simply send its rusting hulk sliding into the deep. This was certainly China’s hope, as any direct assault against the still-commissioned (but utterly unseaworthy) naval vessel would necessitate U.S. involvement under its 1951 mutual defense treaty with the Philippines.

Therefore, Beijing adopted a modified blockade strategy, allowing only small, wooden resupply vessels to approach the grounded ship so that the Philippines could not bring out “construction materials” to improve the outpost—or worse, ground a second ship.

By mid-2023, the Philippines—armed with small coast guard cutters and lots of cameras—was ready to push the envelope to challenge China’s blockade.

This led to a year of increasingly alarming dramatics around Second Thomas Shoal, with growing numbers of Chinese ships intercepting every Philippine resupply mission on the high seas.

Made-for-TV blockade running.

That brings us back to the beleaguered BRP Sierra Madre.

In the quarter-century since its grounding, little had been done to shore up the ship, to the extent that many wondered whether the next large storm might simply send its rusting hulk sliding into the deep. This was certainly China’s hope, as any direct assault against the still-commissioned (but utterly unseaworthy) naval vessel would necessitate U.S. involvement under its 1951 mutual defense treaty with the Philippines.

Therefore, Beijing adopted a modified blockade strategy, allowing only small, wooden resupply vessels to approach the grounded ship so that the Philippines could not bring out “construction materials” to improve the outpost—or worse, ground a second ship.

By mid-2023, the Philippines—armed with small coast guard cutters and lots of cameras—was ready to push the envelope to challenge China’s blockade.

This led to a year of increasingly alarming dramatics around Second Thomas Shoal, with growing numbers of Chinese ships intercepting every Philippine resupply mission on the high seas.

Water cannons and rammings became standard fare, until a dramatic hand-to-hand confrontation took place on June 17, 2024, in which the Chinese coast guard brandished bladed weapons and a Philippine sailor lost a thumb.

The following month a rickety truce was reached between the two exhausted parties, the terms of which have never been made fully public but seem to be holding up (for now).

This truce did not, however, extend to the rest of the West Philippine Sea, where clashes elsewhere began to take center stage.

This truce did not, however, extend to the rest of the West Philippine Sea, where clashes elsewhere began to take center stage.

Repeatedly blaming U.S. instigation and Philippine provocation as pretext to escalate, China has since tightened its grip on Scarborough Shoal, clamped down for the first time on Sabina Shoal, and begun harassing fishermen around Iroquois Reef.

The strength imperative.

The incoming Trump administration will need to recognize that the perception of weakness is catnip to an expansionist power, and China has proved itself no exception to this rule.

The strength imperative.

The incoming Trump administration will need to recognize that the perception of weakness is catnip to an expansionist power, and China has proved itself no exception to this rule.

The president-elect will need to decide how to support America’s treaty ally against what has become a full-scale maritime occupation by a hostile imperial power.

Here are a few practical moves the new administration should consider to regain the long-lost initiative:

First, the new administration should announce early its intent to partner with the Philippines to jointly explore Reed Bank, where 55 trillion cubic feet of natural gas are believed to lie but which Beijing’s threats have dissuaded Manila from exploiting.

Here are a few practical moves the new administration should consider to regain the long-lost initiative:

First, the new administration should announce early its intent to partner with the Philippines to jointly explore Reed Bank, where 55 trillion cubic feet of natural gas are believed to lie but which Beijing’s threats have dissuaded Manila from exploiting.

The Duterte administration’s joint development project with China failed when it became clear that Beijing’s price was the weakening of Manila’s legal rights to its own resources.

The U.S. has no such designs, and can make that position explicit from the beginning.

The U.S. should also make it clear that it rejects any assertion by Beijing that American movements through international waters in the South China Sea are subject to China’s veto, and that this right extends beyond its established freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) program to include U.S. Navy and Coast Guard visits to Philippine-held outposts.

The U.S. should also make it clear that it rejects any assertion by Beijing that American movements through international waters in the South China Sea are subject to China’s veto, and that this right extends beyond its established freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) program to include U.S. Navy and Coast Guard visits to Philippine-held outposts.

Where else on the planet do we let another country tell us we can’t go visit our friends?

Specifically, the Philippines maintains a small civilian population at Thitu Island, whose beleaguered residents wake up regularly to harassing swarms of coast guard, militia, and fishing ships asserting China’s sovereignty over the island.

Specifically, the Philippines maintains a small civilian population at Thitu Island, whose beleaguered residents wake up regularly to harassing swarms of coast guard, militia, and fishing ships asserting China’s sovereignty over the island.

The Trump administration can send an early signal of its support and resolve by deploying a joint U.S.-Philippine military and civic-action missionto aid Thitu’s citizens and upgrade the island’s infrastructure.

Beijing can then twist itself into knots explaining how a planeload of doctors and civil engineers somehow represents a threat to peace and stability, while America makes it clear that it’s serious about protecting its investment in its treaty ally.

The U.S. should also explore adding one or two West Philippine Sea outposts to the list of nine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Activitysites we are already now jointly building out with Manila, making it clear that our mutual defense treaty extends to wherever we see a need and our ally requires our aid.

These recommendations will doubtless cause distress in Beijing as well as many regional capitals, both because they fear escalation and because some have their own competing claims.

The U.S. should also explore adding one or two West Philippine Sea outposts to the list of nine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Activitysites we are already now jointly building out with Manila, making it clear that our mutual defense treaty extends to wherever we see a need and our ally requires our aid.

These recommendations will doubtless cause distress in Beijing as well as many regional capitals, both because they fear escalation and because some have their own competing claims.

These are not risk-free moves for the U.S., but caution in the South China Sea has thus far yielded nothing but a gradual slouch toward defeat.

The U.S. has consistently arrived late to brushups in a gray-zone conflict that has been underway for decades. We have for too long clung to a paradigm that our role is merely to voice our opposition to changing the status quo and peacefully resolve disputes.

The U.S. has consistently arrived late to brushups in a gray-zone conflict that has been underway for decades. We have for too long clung to a paradigm that our role is merely to voice our opposition to changing the status quo and peacefully resolve disputes.

Beijing has stolen several marches on us by employing a gray zone strategy for which we have had no response.

When in 2020 President Trump announced he would move America’s embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, he knew there would be hand-wringing and pearl-clutching from all the familiar places.

When in 2020 President Trump announced he would move America’s embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, he knew there would be hand-wringing and pearl-clutching from all the familiar places.

That’s what made it a bold move, and ultimately a successful one.

The South China Sea demands no less resolve and decisiveness, before China completes its campaign of maritime occupation and area denial, and the window of opportunity for new approaches to slams shut.

The South China Sea demands no less resolve and decisiveness, before China completes its campaign of maritime occupation and area denial, and the window of opportunity for new approaches to slams shut.

Links :

Thursday, January 16, 2025

A gigantic wave in the Pacific Ocean was the most extreme 'Rogue Wave' on record

Rogue waves can reach heights of over 100 feet 😳pic.twitter.com/l1JDvyfnt7

— UberFacts (@UberFacts) March 24, 2023

Rogue waves can reach heights of over 100 feet

From Science Alert by Carly Cassella

In November of 2020, a freak wave came out of the blue, lifting a lonesome buoy off the coast of British Columbia 17.6 meters high (58 feet).

The four-story wall of water was finally confirmed in February 2022 as the most extreme rogue wave ever recorded at the time.

Such an exceptional event is thought to occur only once every 1,300 years.

And unless the buoy had been taken for a ride, we might never have known it even happened.

11. The size of these waves are incredible! It takes some balls to do these jobs! Massive respect ✊pic.twitter.com/qIEoecr3L8

— Vertigo_Warrior (@VertigoWarrior) January 15, 2025

For centuries, rogue waves were considered nothing but nautical folklore.

It wasn't until 1995 that myth became fact.

On the first day of the new year, a nearly 26-meter-high wave (85 feet) suddenly struck an oil-drilling platform roughly 160 kilometers (100 miles) off the coast of Norway.

Large wave in Nazaré, Portugal, where the record was set for the biggest wave ever surfed in 2017. (Alexander Ehlers/Getty Images Plus)

Large wave in Nazaré, Portugal, where the record was set for the biggest wave ever surfed in 2017. (Alexander Ehlers/Getty Images Plus)At the time, the so-called Draupner wave defied all previous models scientists had put together.

Since then, dozens more rogue waves have been recorded (some even in lakes), and while the one that surfaced near Ucluelet, Vancouver Island was not the tallest, its relative size compared to the waves around it was unprecedented.

Video reconstruction of the »New Years Wave«, from BBC documentary.

The »New Years Wave« or »Draupner Wave« was a Monster wave in the North Sea 1995.

The Oil Rig is the Draupner Oil Rig, run by Strato.

This one is appr. 30m high.

Scientists define a rogue wave as any wave more than twice the height of the waves surrounding it.

The Draupner wave, for instance, was 25.6 meters tall, while its neighbors were only 12 meters tall.

In comparison, the Ucluelet wave was nearly three times the size of its peers.

"Proportionally, the Ucluelet wave is likely the most extreme rogue wave ever recorded," explained physicist Johannes Gemmrich from the University of Victoria in 2022.

"Only a few rogue waves in high sea states have been observed directly, and nothing of this magnitude."

Today, researchers are still trying to figure out how rogue waves are formed so we can better predict when they will arise.

In comparison, the Ucluelet wave was nearly three times the size of its peers.

"Proportionally, the Ucluelet wave is likely the most extreme rogue wave ever recorded," explained physicist Johannes Gemmrich from the University of Victoria in 2022.

"Only a few rogue waves in high sea states have been observed directly, and nothing of this magnitude."

Today, researchers are still trying to figure out how rogue waves are formed so we can better predict when they will arise.

This includes measuring rogue waves in real time and also running models on the way they get whipped

up by the wind.

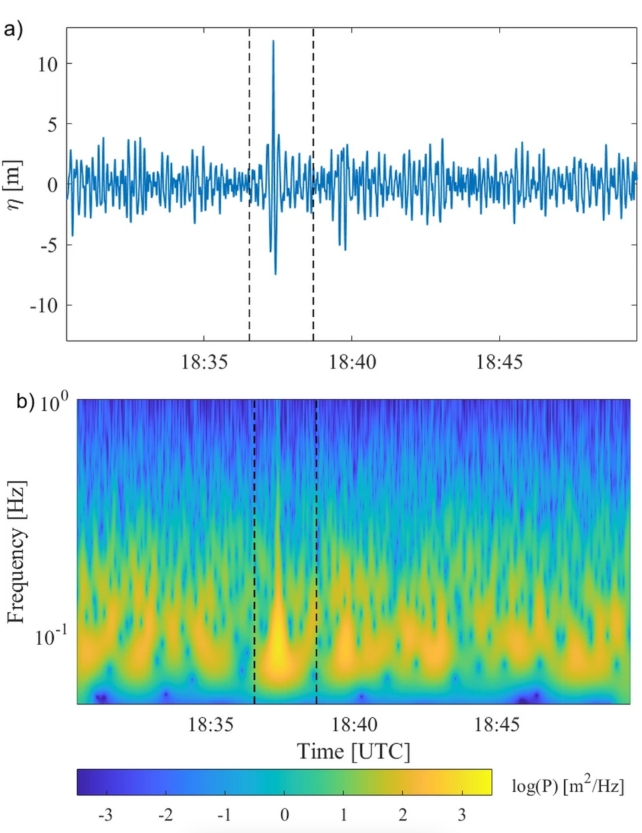

Rogue wave recorded on Nov 17, 2020. Vertical dashed lines indicate the wave group containing the rogue wave.

(a) Surface elevation.

(b) Spectrogram of surface elevation using the Morlet wavelet.

(Gemmrich & Cicon, Scientific Reports, 2022)

The buoy that picked up the Ucluelet wave was placed offshore along with dozens of others by a research institute called MarineLabs in an attempt to learn more about hazards out in the deep.

10. Offshore oil rig in the middle of a sea stormpic.twitter.com/Jke8BnrNQa

— Vertigo_Warrior (@VertigoWarrior) January 15, 2025

Even when freak waves occur far offshore, they can still destroy marine operations, wind farms, or oil rigs.

If they are big enough, they can even put the lives of beachgoers at risk.

Luckily, neither Ucluelet nor Draupner caused any severe damage or took any lives, but other rogue waves have.

Luckily, neither Ucluelet nor Draupner caused any severe damage or took any lives, but other rogue waves have.

A team of researchers at the Universities of Oxford and Edinburgh have worked out how freak waves can happen.

The research was led by Dr Mark McAllister and Prof Ton van den Bremer at the University of Oxford, in collaboration with Dr Sam Draycott at the University of Edinburgh.

This project builds upon work previously carried out at the University of Oxford by Professors Thomas Adcock and Paul Taylor.

The experiments were carried out in the FloWave Ocean Energy Research facility at the University Of Edinburgh.

The leftover floating wreckage looks like the work of an immense white cap.

Unfortunately, a 2020 study predicted wave heights in the North Pacific are going to increase with climate change, which suggests the Ucluelet wave may not hold its record for as long as our current predictions suggest.

Unfortunately, a 2020 study predicted wave heights in the North Pacific are going to increase with climate change, which suggests the Ucluelet wave may not hold its record for as long as our current predictions suggest.

A simulation of the MarineLabs buoy riding a rogue wave off the coast of Ucluelet, Vancouver Island

in November, 2020

in November, 2020

Experimental research published last year suggests these monstrous waves can be up to four times higher than previously thought possible.

"We are aiming to improve safety and decision-making for marine operations and coastal communities through widespread measurement of the world's coastlines," said MarineLabs CEO Scott Beatty.

"Capturing this once-in-a-millennium wave, right in our backyard, is a thrilling indicator of the power of coastal intelligence to transform marine safety."

"We are aiming to improve safety and decision-making for marine operations and coastal communities through widespread measurement of the world's coastlines," said MarineLabs CEO Scott Beatty.

"Capturing this once-in-a-millennium wave, right in our backyard, is a thrilling indicator of the power of coastal intelligence to transform marine safety."

Links :

- The study was published in Scientific Reports

- Newswire : Record-Breaking Rogue Wave Recorded off the Coast of Vancouver Island

- Earth : Most extreme "rogue wave" ever recorded in the Pacific Ocean detailed in new study

- ResearchGate : The physics of anomalous ('rogue') ocean waves

- Tudelft : Unusual waves grow way beyond known limits

- QuantaMag : What Causes Giant Rogue Waves?

- The Conversation : How scientists recreated a monster wave that looks like Hokusai’s famous image

- GeoGarage blog : Rogue waves in the ocean are much more common than ... / Enormous 'rogue waves' can appear out of nowhere. Math ... / Terrifying 20m-tall 'rogue waves' are actually real / Study finds massive rogue waves aren't as rare ... / Oxford scientists successfully recreated a famous rogue ... / How rogue waves are created in the ocean / Theories of giant waves that suddenly appear and vanish / Four-story high rogue wave breaks records off the coast of ... / How dangerous can ocean waves get? Wave comparison / Rogue wave theory to save ships / Rogue waves captured / The Bermuda Triangle: A breeding ground for rogue waves ... / 19-meter wave sets new record - highest significant ... / The Power of the SEA: tsunamis, storm surges, rogue ... / NZ tech could reveal planet's largest waves / Rough seas for tough mariners

Wednesday, January 15, 2025

Understanding 'Notices to Mariners': their role & importance in maritime navigation

From VirtueMarine

Navigating the vast and unpredictable oceans requires more than just a sturdy vessel and a skilled crew; it demands up-to-date information to ensure safe passage.

This is where Notices to Mariners come into play.

These essential updates provide mariners with critical information about changes in navigational aids, hazards, and other important maritime details.

By staying informed through these notices, mariners can avoid potential dangers and ensure the safety of their voyage.

In this article, we'll explore the significance of Notices to Mariners and how they play a pivotal role in maritime navigation.

The timely distribution and incorporation of NtM into nautical charts and publications are legally required for coastal states.

This is mandated by international maritime conventions.

The commitment to providing accurate and current navigational information is fundamental to maintaining safety at sea.

Mariners depend on these notices to make informed decisions, avoid potential dangers, and adhere to the latest maritime regulations and best practices.

The significance of Notices to Mariners cannot be overstated.

They act as a lifeline for mariners, offering the most current navigational warnings, coastal updates, and changes to aids to navigation.

Without these notices, vessels would face uncharted hazards, leading to potential accidents, environmental disasters, and loss of life.

By utilizing NtM, mariners can navigate with confidence, knowing they have access to the latest critical information for a safe voyage.

Key Takeaways

- Notices to Mariners are essential for sharing critical maritime safety information

- Coastal states are obligated to provide accurate and timely NtM

- NtM are vital for updating nautical charts and publications

- Mariners rely on NtM to navigate safely and avoid potential hazards

- Staying informed through NtM is crucial for maintaining safety at sea

Notices to Mariners (NtM) are critical publications that offer maritime safety updates and essential information for safe navigation at sea.

These notices include corrections to nautical charts, navigational warnings, and changes to aids to navigation.

They are issued regularly by various countries to ensure mariners have the most current and accurate data for safe navigation.

Definition and Purpose of NtM

NtMs are official publications that alert mariners to important changes affecting nautical charts and navigational safety.

Their primary purpose is to provide timely information about hydrography changes, newly discovered hazards, and updates to navigational aids.

By keeping their nautical products current with the latest NtMs, mariners can maintain situational awareness and navigate safely.

Obligation of Coastal States to Provide NtM

International maritime law mandates that every coastal state chart its coastal waters and share this information through NtMs.

This ensures that all vessels navigating in these waters have access to accurate and up-to-date navigational data.

Over 60 countries produce NtMs, with varying frequencies of publication:

- One-third of NtMs are issued weekly

- Another third are published bi-monthly or monthly

- The remaining NtMs are issued irregularly, as needed

The U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office has been issuing weekly NtMs since 1886.

In the United States, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Ocean Service (NOS), and U.S. Coast Guard collaborate to publish the weekly Notice to Mariners.

The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) releases its Notice to Mariners publication monthly.

By staying informed about the latest marine navigation alerts and promptly updating their nautical charts and publications, mariners can significantly enhance maritime navigation safety and comply with international regulations.

Types of Notices to Mariners

Notices to Mariners (NtM) encompass diverse forms, each with a distinct purpose in sharing essential marine safety information and navigational charts corrections.

These notices are crucial for maintaining the maritime sector's awareness of the latest nautical charts updates and other pertinent news.

Local Notice to Mariners (LNM)

Local Notice to Mariners (LNM) are shared by each Coast Guard district, offering information specific to their jurisdiction.

These notices address a broad spectrum of topics, including alterations to aids to navigation, temporary and permanent modifications to waterways, and critical safety advisories.

Local Notice to Mariners (LNM) are shared by each Coast Guard district, offering information specific to their jurisdiction.

These notices address a broad spectrum of topics, including alterations to aids to navigation, temporary and permanent modifications to waterways, and critical safety advisories.

Broadcast Notice to Mariners (BNM)

Broadcast Notice to Mariners (BNM) serve as urgent safety advisories broadcast by the Coast Guard via radio stations.

They deliver immediate alerts regarding hazards to navigation, such as drifting debris, malfunctioning aids to navigation, or other urgent matters necessitating prompt action from mariners.

They deliver immediate alerts regarding hazards to navigation, such as drifting debris, malfunctioning aids to navigation, or other urgent matters necessitating prompt action from mariners.

Special Notice to Mariners (SNM)

Special Notice to Mariners (SNM) encapsulate critical annual information for mariners operating within a particular region.

These notices detail seasonal buoy modifications, special events influencing navigation, or other enduring alterations to the maritime environment.

Updates on sailing directions and miscellaneous nautical publications

By remaining abreast of the various Notices to Mariners and consistently updating their charts and publications, mariners can guarantee safe and efficient navigation.

This adherence to international regulations enhances the overall safety of the maritime industry.

Content of Notices to Mariners

Notices to Mariners (NtM) are vital for sharing critical marine navigation notices.

They ensure the safety and efficiency of maritime operations.

These notices cover a wide range of topics, from corrections to nautical charts and publications to navigational warnings and hazards.

One of the primary functions of NtM is to provide updates and corrections to nautical charts and publications.

These documents are essential for safe navigation.

It is crucial that they are kept up-to-date with the latest information.

NtM inform mariners about changes in depths, obstructions, and other critical details that may affect their voyage planning and execution.

Navigational Warnings and Hazards

NtM also serve as a platform for issuing navigational warnings and alerts about potential hazards.

These may include reports of floating debris, ice formations, or other obstacles that could pose a risk to vessels.

By promptly sharing this information, NtM help mariners make informed decisions and take appropriate precautions to ensure their safety and that of their crew and cargo.

Special Notice to Mariners (SNM) encapsulate critical annual information for mariners operating within a particular region.

These notices detail seasonal buoy modifications, special events influencing navigation, or other enduring alterations to the maritime environment.

Updates on sailing directions and miscellaneous nautical publications

By remaining abreast of the various Notices to Mariners and consistently updating their charts and publications, mariners can guarantee safe and efficient navigation.

This adherence to international regulations enhances the overall safety of the maritime industry.

Content of Notices to Mariners

Notices to Mariners (NtM) are vital for sharing critical marine navigation notices.

They ensure the safety and efficiency of maritime operations.

These notices cover a wide range of topics, from corrections to nautical charts and publications to navigational warnings and hazards.

One of the primary functions of NtM is to provide updates and corrections to nautical charts and publications.

These documents are essential for safe navigation.

It is crucial that they are kept up-to-date with the latest information.

NtM inform mariners about changes in depths, obstructions, and other critical details that may affect their voyage planning and execution.

Navigational Warnings and Hazards

NtM also serve as a platform for issuing navigational warnings and alerts about potential hazards.

These may include reports of floating debris, ice formations, or other obstacles that could pose a risk to vessels.

By promptly sharing this information, NtM help mariners make informed decisions and take appropriate precautions to ensure their safety and that of their crew and cargo.

Changes to Aids to Navigation

Another critical aspect covered by NtM is changes to aids to navigation, such as lighthouses, buoys, and beacons.

These aids play a vital role in guiding vessels safely through waterways.

Any alterations or malfunctions must be promptly communicated to mariners.

NtM provide details on the location, characteristics, and status of these aids, enabling mariners to navigate with confidence and precision.

Other Important Marine Information

In addition to the above, NtM also include a wealth of other important marine information.

This may encompass details on naval operations, regattas, and other events that may affect vessel traffic in specific areas.

NtM provide valuable insights into hydrographic surveys and channel depths.

This empowers mariners to plan their routes effectively and avoid potential groundings or collisions.

By providing this comprehensive range of navigational safety updates and marine navigation safety tips, Notices to Mariners serve as an indispensable resource for the maritime community.

They ensure that mariners have access to the most current and accurate information.

This enables them to navigate the world's waterways safely and efficiently.

Accessing and Staying Up-to-Date with NtM

Ensuring safe navigation on the seas necessitates the most current and precise marine navigation data.

Notices to Mariners (NtM) deliver vital maritime navigation safety advisories and updates, imperative for all mariners.

It is crucial to remain current with NtM to safeguard vessels, crew, and cargo.

In addition to the above, NtM also include a wealth of other important marine information.

This may encompass details on naval operations, regattas, and other events that may affect vessel traffic in specific areas.

NtM provide valuable insights into hydrographic surveys and channel depths.

This empowers mariners to plan their routes effectively and avoid potential groundings or collisions.

By providing this comprehensive range of navigational safety updates and marine navigation safety tips, Notices to Mariners serve as an indispensable resource for the maritime community.

They ensure that mariners have access to the most current and accurate information.

This enables them to navigate the world's waterways safely and efficiently.

Accessing and Staying Up-to-Date with NtM

Ensuring safe navigation on the seas necessitates the most current and precise marine navigation data.

Notices to Mariners (NtM) deliver vital maritime navigation safety advisories and updates, imperative for all mariners.

It is crucial to remain current with NtM to safeguard vessels, crew, and cargo.

Weekly Publications and Printable Versions

Maritime authorities publish Notices to Mariners on a weekly basis.

These are accessible in printable formats, facilitating mariners' ability to access and reference the latest marine navigation safety updates.

Weekly NtM publications encompass a broad spectrum of topics, including corrections to nautical charts, navigational warnings, and changes to aids to navigation.

Overview of NtM by Week and Chart

NtM publications often organize notices by week and chart, simplifying navigation and referencing.

This structure enables mariners to swiftly identify pertinent marine navigation information for their specific operational areas.

The overview typically summarizes key changes and updates, along with references to affected charts and publications.

Obtaining NtM through Selected Agents

Mariners can also acquire NtM through selected agents, in addition to weekly publications.

These agents, authorized by maritime authorities, distribute marine navigation safety notices and updates.

While some agents may charge a fee, it provides an alternative for accessing critical navigation information.

Mariners operating in multiple regions or Coast Guard districts must obtain NtM from each relevant authority.

This ensures they remain informed about marine navigation safety updates specific to their operational areas.

Navigational Warnings are broadcast by the Canadian Coast Guard to notify mariners of changes to aids to navigation, followed by Notices to Mariners for updates.

By diligently accessing and staying current with Notices to Mariners, mariners can ensure they have the most up-to-date and accurate marine navigation information.

This enables them to navigate the seas safely and efficiently.

Reporting Uncharted Dangers, Changes, or Errors

Maritime authorities publish Notices to Mariners on a weekly basis.

These are accessible in printable formats, facilitating mariners' ability to access and reference the latest marine navigation safety updates.

Weekly NtM publications encompass a broad spectrum of topics, including corrections to nautical charts, navigational warnings, and changes to aids to navigation.

Overview of NtM by Week and Chart

NtM publications often organize notices by week and chart, simplifying navigation and referencing.

This structure enables mariners to swiftly identify pertinent marine navigation information for their specific operational areas.

The overview typically summarizes key changes and updates, along with references to affected charts and publications.

Obtaining NtM through Selected Agents

Mariners can also acquire NtM through selected agents, in addition to weekly publications.

These agents, authorized by maritime authorities, distribute marine navigation safety notices and updates.

While some agents may charge a fee, it provides an alternative for accessing critical navigation information.

Mariners operating in multiple regions or Coast Guard districts must obtain NtM from each relevant authority.

This ensures they remain informed about marine navigation safety updates specific to their operational areas.

Navigational Warnings are broadcast by the Canadian Coast Guard to notify mariners of changes to aids to navigation, followed by Notices to Mariners for updates.

By diligently accessing and staying current with Notices to Mariners, mariners can ensure they have the most up-to-date and accurate marine navigation information.

This enables them to navigate the seas safely and efficiently.

Reporting Uncharted Dangers, Changes, or Errors

Mariners are pivotal in upholding maritime sector safety by alerting authorities to uncharted dangers, changes, or errors in nautical products.

This collective effort ensures the precision and thoroughness of nautical navigation alerts.

It fosters marine navigation safety information across the maritime domain.

Modern tankers must report any depth under 30 meters.

Reports of shoal soundings, uncharted dangers, and issues with aids to navigation can be radioed to the nearest coast radio station.

Even with incomplete information, reports should be made with as much detail as possible for verification.

Accurate location details are essential when reporting.

Latitude and Longitude should only be specified when fixed by GPS or Astronomical Observations.

Upon receiving Hydrographic Notes, the National Hydrographic Office sends an acknowledgment, using the sender's ship or name as authority for the reported data.

Changes to port information are to be submitted on Form IH.102A along with Form IH.102.

Additional sheets are available if necessary due to space limitations on the forms.

Navigational reports are categorized into Safety Reports, Sounding Reports, Marine Data Reports, and Port Information Reports.

This collective effort ensures the precision and thoroughness of nautical navigation alerts.

It fosters marine navigation safety information across the maritime domain.

Modern tankers must report any depth under 30 meters.

Reports of shoal soundings, uncharted dangers, and issues with aids to navigation can be radioed to the nearest coast radio station.

Even with incomplete information, reports should be made with as much detail as possible for verification.

Accurate location details are essential when reporting.

Latitude and Longitude should only be specified when fixed by GPS or Astronomical Observations.

Upon receiving Hydrographic Notes, the National Hydrographic Office sends an acknowledgment, using the sender's ship or name as authority for the reported data.

Changes to port information are to be submitted on Form IH.102A along with Form IH.102.

Additional sheets are available if necessary due to space limitations on the forms.

Navigational reports are categorized into Safety Reports, Sounding Reports, Marine Data Reports, and Port Information Reports.

Organization Responsibility

U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office (NAVOCEANO)

- Conducts hydrographic and oceanographic surveys of foreign or international waters

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- Provides charts for marine and air navigation in the coastal waters of the United States and its territories

Collects, analyzes, and shares navigational and oceanographic data, ensuring safety at sea and improving the marine environment

Reports on ice concentrations, thickness, and position, as well as floating derelicts, wrecks, man-made obstructions, and shoals, are crucial.

They ensure accurate charting and navigation safety.

Discolored water sightings are also significant, indicating various underwater features, pollution or disturbances.

Mariner reports are vital for updating and maintaining accurate nautical navigation alerts and publications.

U.S. Coast Guard Districts and NtM Responsibilities

The United States Coast Guard is crucial in maintaining maritime navigation safety by sharing Notices to Mariners (NtM) for their respective districts.

These notices are essential for mariners to navigate safely within U.S. waters.

They include updates, regulations, alerts, and notices.

Division of U.S. into Coast Guard Districts

The U.S. is segmented into several Coast Guard Districts to manage maritime navigation safety effectively.

Each district is responsible for issuing Local Notices to Mariners (LNM) for their specific region.

The districts span various areas:

- District 1: Maine to northern New Jersey

- District 5: Southern New Jersey to North Carolina

- District 7: South Carolina to Florida and the Caribbean

- District 8: Gulf Coast from Florida to Mexico

- District 9: Great Lakes region

- District 11: California and Arizona

- District 13: Oregon and Washington

- District 14: Hawaii and the Pacific Islands

- District 17: Alaska

Mariners can report any changes, errors, or uncharted dangers to the appropriate Coast Guard District.

By contacting the appropriate Coast Guard District, mariners can ensure adherence to marine navigation safety regulations.

They can also receive timely maritime navigation safety alerts or notices.

Importance of NtM for SOLAS Compliance

Notices to Mariners (NtM) are essential for adhering to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS).

This treaty requires the use of official nautical products, including NtM, for safe navigation.

Mariners can follow maritime safety regulations and receive vital navigational safety updates by using current NtM information.

Statistics underscore the importance of NtM in maritime safety and compliance.

For example, 20% of NtM are about Ballast Water Management for Control of Non-Indigenous Species.

Also, 15% concern Vessel Security Regulations: MTSA and ISPS Code.

Further, 11% are safety warnings and signals, highlighting the role of communication in marine navigation safety.

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)

SOLAS is a pivotal international treaty that establishes minimum safety standards for ships.

Compliance with SOLAS is crucial for vessels on international voyages.

By 2018, all cargo ships, tankers, passenger ships, and mega yachts must use Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems (ECDIS) as their primary navigation tool to meet SOLAS requirements.

Vessel Type

ECDIS Requirement

- Cargo Ships

- Mandatory

- Tankers

- Mandatory

- Passenger Ships

- Mandatory

- Mega Yachts

- Mandatory

Mariner's Obligation to Use Official Nautical Products

Mariners must use official nautical products, including NtM, to comply with SOLAS and ensure safe navigation.

This entails regularly updating nautical charts and electronic navigation systems with the latest NtM corrections and information.

Such actions provide mariners with critical marine navigation safety tips and updates on hazards, regulatory changes, and other essential information.

Mariners should consult with electronic chart suppliers to ensure the timely acquisition of necessary updates for the chart portfolio.

In conclusion, NtM are vital for mariners to comply with SOLAS regulations and uphold maritime safety standards.

By keeping abreast of the latest NtM information, mariners can navigate confidently and contribute to a safer maritime environment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, notices to mariners are vital for maritime safety, offering critical updates and corrections to nautical charts and publications.

Given that over 90% of global trade is transported by sea, the necessity for precise and current maritime safety information is paramount.

Research indicates that vessels that monitor and act on marine navigation alerts are significantly less likely to be involved in maritime mishaps.

The failure to heed nautical warnings is a primary cause of maritime accidents, as highlighted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

More than 60% of maritime incidents stem from navigational errors, underscoring the pivotal role of nautical warnings in averting such calamities.

By adhering to notices to mariners, mariners can ensure safe navigation, circumvent dangers, and enhance maritime security.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is instrumental in the production and revision of nautical charts, with 351 new conventional chart editions in fiscal year 1991.

Private entities also contribute to the sharing of nautical charts, with digital hydrographic data sets selling in the tens of thousands annually.

As the maritime sector advances, the significance of timely and accurate nautical charts updates and marine navigation alerts will escalate, ensuring the safety and efficiency of global maritime commerce.

FAQ

What are Notices to Mariners (NtM)?

Notices to Mariners (NtM) are critical documents that share essential maritime navigation updates.

These include corrections to nautical charts and publications, navigational warnings, and other vital marine data.

Issued by coastal states, they are pivotal for ensuring the safety of vessels and their crews at sea.

Why are Notices to Mariners important for maritime safety?

NtM are indispensable for maintaining safe navigation.

They provide mariners with the latest information on changes, hazards, and corrections in coastal waters.

By keeping their charts and publications current with NtM, mariners adhere to safety regulations, avoid dangers, and contribute to a safer maritime environment.

What types of information are included in Notices to Mariners?

NtM encompass a broad spectrum of information crucial for safe navigation.

This includes corrections to nautical charts and publications, navigational warnings, reports of deficiencies and changes to aids to navigation, positions of ice and derelicts, channel depths, naval operations, regattas, and other hydrographic data affecting vessels and waterways.

What are the different types of Notices to Mariners?

Various types of NtM exist, including Local Notice to Mariners (LNM) issued by each Coast Guard district, Broadcast Notice to Mariners (BNM) shared by the Coast Guard through radio stations, and Special Notice to Mariners (SNM) containing essential annual information for mariners in specific regions.

How can mariners access and stay up-to-date with Notices to Mariners?

NtM are published weekly and accessible in printable formats, weekly overviews, and through selected agents for a fee.

Mariners operating in multiple Coast Guard districts must obtain NtM from each district to remain informed.

Regularly updating nautical products with the latest NtM is imperative for safe navigation.

What should mariners do if they encounter uncharted dangers or errors in nautical products?

By keeping abreast of the latest NtM information, mariners can navigate confidently and contribute to a safer maritime environment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, notices to mariners are vital for maritime safety, offering critical updates and corrections to nautical charts and publications.

Given that over 90% of global trade is transported by sea, the necessity for precise and current maritime safety information is paramount.

Research indicates that vessels that monitor and act on marine navigation alerts are significantly less likely to be involved in maritime mishaps.

The failure to heed nautical warnings is a primary cause of maritime accidents, as highlighted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

More than 60% of maritime incidents stem from navigational errors, underscoring the pivotal role of nautical warnings in averting such calamities.

By adhering to notices to mariners, mariners can ensure safe navigation, circumvent dangers, and enhance maritime security.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is instrumental in the production and revision of nautical charts, with 351 new conventional chart editions in fiscal year 1991.

Private entities also contribute to the sharing of nautical charts, with digital hydrographic data sets selling in the tens of thousands annually.

As the maritime sector advances, the significance of timely and accurate nautical charts updates and marine navigation alerts will escalate, ensuring the safety and efficiency of global maritime commerce.

FAQ

What are Notices to Mariners (NtM)?

Notices to Mariners (NtM) are critical documents that share essential maritime navigation updates.

These include corrections to nautical charts and publications, navigational warnings, and other vital marine data.

Issued by coastal states, they are pivotal for ensuring the safety of vessels and their crews at sea.

Why are Notices to Mariners important for maritime safety?

NtM are indispensable for maintaining safe navigation.

They provide mariners with the latest information on changes, hazards, and corrections in coastal waters.

By keeping their charts and publications current with NtM, mariners adhere to safety regulations, avoid dangers, and contribute to a safer maritime environment.

What types of information are included in Notices to Mariners?

NtM encompass a broad spectrum of information crucial for safe navigation.

This includes corrections to nautical charts and publications, navigational warnings, reports of deficiencies and changes to aids to navigation, positions of ice and derelicts, channel depths, naval operations, regattas, and other hydrographic data affecting vessels and waterways.

What are the different types of Notices to Mariners?

Various types of NtM exist, including Local Notice to Mariners (LNM) issued by each Coast Guard district, Broadcast Notice to Mariners (BNM) shared by the Coast Guard through radio stations, and Special Notice to Mariners (SNM) containing essential annual information for mariners in specific regions.

How can mariners access and stay up-to-date with Notices to Mariners?

NtM are published weekly and accessible in printable formats, weekly overviews, and through selected agents for a fee.

Mariners operating in multiple Coast Guard districts must obtain NtM from each district to remain informed.

Regularly updating nautical products with the latest NtM is imperative for safe navigation.

What should mariners do if they encounter uncharted dangers or errors in nautical products?

Mariners are urged to report any uncharted dangers, changes, or errors in nautical products to the relevant authorities.

This action aids in maintaining the accuracy and completeness of NtM, enhancing safety for the maritime community as a whole.

How does the U.S. Coast Guard manage Notices to Mariners?

The U.S. Coast Guard divides the country into districts, each issuing Local Notice to Mariners (LNM) within their jurisdiction.

These districts span from Maine to Alaska, offering contact information for mariners to report changes or obtain NtM.

Are Notices to Mariners mandatory for compliance with international maritime safety regulations?

Yes, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) mandates the use of official nautical products, including NtM, for safe navigation.

Mariners are obligated to utilize these products and update them regularly to comply with international safety standards.

Source Links

- Merchant shipping notices (MSNs) - https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/merchant-shipping-notices-msns

- About Notices to Mariners - https://msi.admiralty.co.uk/NoticesToMariners/About

- Notice to mariners - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Notice_to_mariners

- Current Notice to Mariners - https://www.cmassets.co.uk/harbours/notice-to-mariners/

- Annual Summary of Notices to Mariners : What is NP247(1)? - https://www.marineinsight.com/marine-navigation/annual-summary-of-notices-to-mariners-what-is-np2471/

- PDF - https://www.traficom.fi/sites/default/files/media/file/tm_info_eng.pdf

- Annual Summary of Notices to Mariners: What is NP 247(2)? - https://www.marineinsight.com/maritime-law/annual-summary-of-notices-to-mariners-what-is-np-2472/

- Keeping charts up to date is important for safe navigation - https://safety4sea.com/keeping-charts-up-to-date-is-important-for-safe-navigation/

- LNM Frequently Asked Questions | Navigation Center - https://www.navcen.uscg.gov/lnm-frequently-asked-questions

- Hydrographic data, nautical charts and nautical publications - https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/Charts.aspx

- Notices to Mariners - https://www.rya.org.uk/knowledge/safety/have-a-plan/notices-to-mariners

- Australian Hydrographic Office - About Australian Notices to Mariners - https://www.hydro.gov.au/n2m/about-notices.htm

- Notice 35 - 39 February 2011 Supplied Gratis - http://www.sanho.co.za/notices_mariners/2020_Series/10_OCT 20 NTM.pdf

- Microsoft Word - 10 Section - https://hydrobharat.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Hydrographic-Note-Filling-Instructions.pdf

- PDF - https://thenauticalalmanac.com/2017_Bowditch-_American_Practical_Navigator/Volume-_1/09- Part 7- Navigational Safety/Chapter 31- Reporting.pdf

- PDF - https://nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/publications/coast-pilot/files/cp2/CPB2_C01_WEB.pdf

- AC 450.161-1 Control of Hazard Areas - https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_450.161-1_Control_of_Hazard_Areas.pdf

- PDF - https://nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/publications/coast-pilot/files/cp9/CPB9_C01_WEB.pdf

- Special_Notice - https://msi.nga.mil/api/publications/download?key=16694429/SFH00000/UNTM/202001/Special_Notice.pdf&type=view

- S-65 Ed 2.1.0 - https://iho.int/iho_pubs/standard/S-65/S-65_ed2 1 0_June17.pdf

- ECDIS & Chart Types: A Guide - https://www.amnautical.com/blogs/news/17037716-ecdis-vector-charts-raster-charts?srsltid=AfmBOopJE3YVHcOk-TkE7gCeKnb9VwBav9tlC_NkfCnPwS7ZEJBC5gmQ

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Meteorologists are keeping an eye on the Caribbean for possible storm development

Clouds

at sunset near the islands in the Indigenous Guna Yala Comarca, Panama,

in the Caribbean Sea, on Aug. 28, 2023.

Clouds

at sunset near the islands in the Indigenous Guna Yala Comarca, Panama,

in the Caribbean Sea, on Aug. 28, 2023.(Lusi Acosta/AFP via Getty Images)

From WP by Matthew Cappucci

If something materializes, it could be the last hurricane of the 2024 season.

Hurricane season is waning, but it’s not over yet.

Meteorologists are monitoring the western Caribbean for possible storm development toward the end of the month.

The next name on the list is “Patty.”

The forecast is far from set in stone.

While there’s a lot of uncertainty, weather models are highlighting the risk of a pocket of spin that could consolidate into a named storm.

It’s too early to speculate on possible strength or track — especially since there isn’t even a storm yet.

But there’s a chance that this system could end up as the final hurricane churning in the Atlantic before the oceans cool and the calendar flips to 2024.

The European model highlights the western Caribbean as a region to watch.

(WeatherBell)

(WeatherBell)

What we’re watching

It’s worth noting that, even if a storm forms, the odds of a U.S.impact are slim.

Only four hurricanes in the past century and a half have struck the Lower 48 during November; records date back to near 1850.

The Atlantic has had a busy season.

The ACE, or Accumulated Cyclone Energy — a metric which gauges how much energy storms churn through to produce strong winds — is running 30 percent above average.

It still falls short of the “hyperactive” season projected by experts, yet it didn’t take a hyperactive season to bring serious impact.

The U.S. was hit by five hurricanes — Beryl, Debby, Francine, Helene and Milton.

Four slammed Florida.

It’s been the third-costliest season on record.

Helene, which caused catastrophic inland flooding across the Carolinas in the Appalachians and foothills, became the deadliest hurricane to make landfall on the U.S. mainland since Katrina.

More than 200 were killed.

Weather models are indicating the potential for a CAG, or Central American Gyre, to form.

That’s a broad zone of weak spin over Central America and the Caribbean.

CAGs usually last between two and five days.

Since the spin is diffuse, the gyres themselves aren’t ordinarily a concern.

They simply bring unsettled weather, with clouds, showers and a few thunderstorms.

But when thunderstorm complexes help consolidate that spin, that’s when it could tighten and organize into a named storm.

Weather models have historically struggled to simulate specifics of CAG evolution.

In other words, they have a difficult time pinpointing where and when a lobe of spin will amalgamate.

That said, the Caribbean is still red hot; oceanic heat content, or hurricane fuel, abounds, and the atmosphere is still plenty supportive for a named storm to form.

When a storm might form

If a storm does organize, it will be right around Halloween.

That’s also when a batch of upward-moving air will move over the Atlantic, making it easier for storms to form.

That will come with something called a Convectively-Coupled Kelvin Wave, or a broad overturning circulation that meanders about the global tropics.

The “enhanced” phase is commonly associated with an uptick in tropical activity.

If something does form in the western Caribbean, it’s too early to know whether it would have any chance of entering the Gulf.

This time of year, storms that form in the Caribbean are more likely to drift west; slipping north or northeast would require an absence of cold fronts or disruptive high-altitude winds.

For now, Jamaica, Central America, Cuba and/or Yucatán Mexico should keep tabs on the western Caribbean.

Monday, January 13, 2025

Sticks, stars : How early charts plotted the way we were

From MSN by Sukanya Datta

If you wanted to know when the bison were returning, and when to expect the next hearty steak, you likely checked the latest cave update, in Ancient Lascaux, France.

For nearly a century, ever since the caves were discovered in 1940, anthropologists have struggled to decode the lines, dots and Y-shaped marks carved into the rock here.

Now, in a study published last year, researchers from Durham University and University College London, analysed 800 such sequences and found that they contained 13 types of marks (sets of lines, dots and Y symbols), in patterns consistent with the 13 months in a lunar year.

Suddenly, the message of the marks became clearer: they could represent the mating, migration and birthing patterns of the deer, bison and horses drawn alongside.

No one likely lived in the Lascaux caves; they were more of an art and information centre.

And so these marks, made 17,000 to 20,000 years ago, could represent the earliest public data charts in the world.

Go further back, as much as 50,000 years ago, and bones have been found across Africa and parts of Eastern Europe, with notches in them that coincide with the phases of the moon.

Go further back, as much as 50,000 years ago, and bones have been found across Africa and parts of Eastern Europe, with notches in them that coincide with the phases of the moon.

These bones would have acted as a sort of early calendar.

These systems, of knots, notches and dashes, would endure for tens of thousands of years.

As recently as the 15th century, in South America — in the vast but largely isolated Inca civilisation that operated without money and without a script — a system of knotted ropes called quipu were used to track transactions and debt; record census data; and track stocks of royal grain reserves.

We have been visualising data in one way or another, then, since more or less the start of collective living.

Charts came before language. Before trade. Before poetry. Because, before tales of love and heroism, we had to tackle the question of how to track: the new sheep added to a flock, the days left before the wildebeest moved south, the number of people in a kingdom or the number of soldiers lost at war.

What would come later was the qualitative and quantitative analysis, says Venkatesh Rajamanickam, a professor of information graphics and data visualisation at the Industrial Design Centre of the Indian Institute of Technology-Bombay (IIT-B).

“How do festivals make us ‘feel’? What is it like to work in the office versus at home? That came later. But it is only when you record that you can analyse,” he says.

What were some of the earliest charts like?

These systems, of knots, notches and dashes, would endure for tens of thousands of years.

As recently as the 15th century, in South America — in the vast but largely isolated Inca civilisation that operated without money and without a script — a system of knotted ropes called quipu were used to track transactions and debt; record census data; and track stocks of royal grain reserves.

We have been visualising data in one way or another, then, since more or less the start of collective living.

Charts came before language. Before trade. Before poetry. Because, before tales of love and heroism, we had to tackle the question of how to track: the new sheep added to a flock, the days left before the wildebeest moved south, the number of people in a kingdom or the number of soldiers lost at war.

What would come later was the qualitative and quantitative analysis, says Venkatesh Rajamanickam, a professor of information graphics and data visualisation at the Industrial Design Centre of the Indian Institute of Technology-Bombay (IIT-B).

“How do festivals make us ‘feel’? What is it like to work in the office versus at home? That came later. But it is only when you record that you can analyse,” he says.

What were some of the earliest charts like?

Take a look.

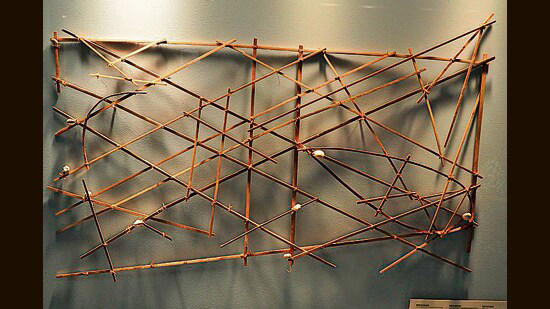

Stick sea charts; Marshall Islands

(Wikimedia)

Stick sea charts; Marshall Islands

(Wikimedia)

For thousands of years, the cluster of about 34 islands and atolls that make up the Marshall Islands used a sort of nautical map to visualise the complex math of tides, currents and ocean swells.

Curved bamboo or pandanus root sticks represented ocean swells; straight twigs stood in for currents and waves; seashells were the islands themselves.

“In a coastal environment, these sticks and shells were a practical choice,” says Rajamanickam. “They could weather rain and seawater, and were easy to carry. The Marshallese would study the charts on land before venturing into the sea.”

Star maps; China

A representation of the Suzhou star chart from the Song Dynasty, China. (Wikimedia)

In Ancient China, star maps were painted and etched onto the ceilings of tombs, onto stone tablets and onto scrolls, in what were likely attempts to help the dead navigate the heavens.

These charts were also used to create calendars, predict celestial events such as eclipses and make astrological divinations.

They helped in early attempts at astronomy.

A particularly interesting such map is a tomb painting dating to 1116 CE. It shows the Great Bear or Ursa Major constellation, depicted as seven red dots connected by lines.

A particularly interesting such map is a tomb painting dating to 1116 CE. It shows the Great Bear or Ursa Major constellation, depicted as seven red dots connected by lines.

At a distance are nine small discs of varying sizes, believed to indicate the sun, moon and five naked-eye and two invisible planets.

Links :

Links :

Sunday, January 12, 2025

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)