What would an oil spill in the Beaufort Sea look like ?

From e360Yale by Ed Strukzik

As the U.S. and Russia take the first steps to drill for oil and gas in the Arctic Ocean, experts say the harsh climate, icy seas, and lack of infrastructure means a sizeable oil spill would be very difficult to clean up and could cause extensive environmental damage.

Last October, an unmanned barge with 950 gallons of fuel on board was in the Beaufort Sea when it broke free from the tug towing it.

The weather was stormy and the tug captain decided it was too dangerous to try to retrieve the barge in turbulent seas.

Ideally, the Canadian Coast Guard would have been on hand to deal with the situation.

But the icebreaker it routinely dispatches to the Beaufort Sea had gone back to Vancouver for the winter.

It would have taken a week for it to return.

In the days that followed, powerful currents swept the barge into Alaskan waters.

The U.S. Coast Guard couldn’t do anything because its one operating icebreaker was stationed in Antarctica at the time.

Canadian and U.S. officials thought the barge would most likely be locked in the ice, or crushed by ice and sink.

It continued to drift, however, and when satellite observers checked last month the barge was about 40 miles off Russia’s Chukchi Peninsula.

Russian attempts to find the barge have been hampered, likely to due to bad weather.

As potential oil spills go, the barge incident is an extremely minor one.

But experts say that the errant barge should be a wake-up call for Arctic nations like the United States, Canada, Russia, Denmark, and Norway that are poised to ramp up shipping, as well as oil and gas drilling, in the Arctic.

Not only does the route of the ghost barge serve as a real-life demonstration of how spilled oil could move across the Arctic, it also illustrates how difficult it will be to contain and clean up oil in a region where roads, ports, airplanes, and icebreakers are few and far between.

In addition, scientists and engineers still don’t fully understand how chemical dispersants and oil collection agents might work in a cold climate, how ice conditions and ocean currents will influence the fate of spilled oil, and how well microbes in the Arctic are able to degrade the hydrocarbons, as they tend to do in warmer climates, such as during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

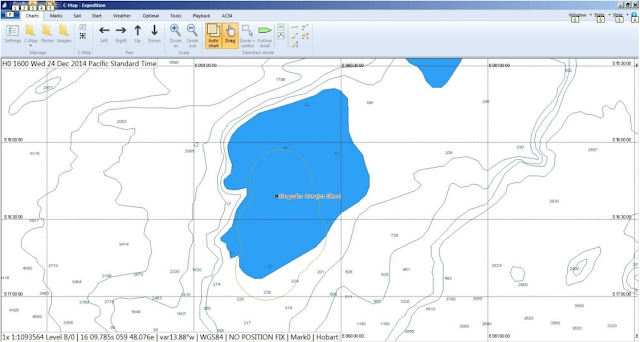

In 2012, WWF commissioned RPS Applied Science Associates, Inc. (RPS ASA) to evaluate different types of oil spills most likely to occur in the Beaufort Sea.

RPS ASA is a world leader in modelling the transport, fate, and biological effects of oil and chemical pollutants in marine environments.

Using cutting-edge computer modelling software, RSP ASA estimated the trajectory future possible oil spills associated with increased ship traffic and offshore petroleum exploration and development in the Beaufort Sea.

“Responding to an oil spill is extremely challenging in any marine environment,” says Paul Crowley, the Canadian director of the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic Program.

“Under Arctic conditions, it is much worse. A major spill would contaminate ice and shorelines for many thousands of kilometers, kill seabirds and mammals, and severely pollute the natural ecosystem that traditional [indigenous] users and wildlife rely upon.”

Crowley noted that the offshore operating season in the Arctic — and therefore the period when it would be possible to clean up an oil spill — is restricted to four to five months by darkness, heavy ice, and extreme cold.

These severe conditions would make it impossible to attempt an oil spill cleanup for half of the time during the operating season, and 100 percent of the time during the winter, Crowley and others say.

The issue of oil spill response in the Arctic has gained added attention since the Obama administration announced last month that it was giving conditional approval to Shell Oil to drill up to six exploratory wells in the Chukchi Sea off Alaska.

Although the U.S. is requiring Shell to abide by stringent safeguards — drilling only in shallow water and only in ice-free months, requiring the presence of a second oil rig to drill a relief well in case of a blowout — the administration’s decision nonetheless opens the door to drilling in U.S. Arctic waters.

Shell also is exploring Arctic oil-drilling opportunities in Russia, Greenland, and Norway.

The company says it is taking “extraordinary precautions” to drill safely and is collaborating closely with scientific organizations and governments in the region.

Using a supposedly ice-resistant platform, Russia has already begun drilling in the Arctic Ocean at the Prirazlomnoye oil field in the Pechora Sea off western Siberia.

These developments, experts warn, may be just the beginning of oil exploitation in a region that is unprepared to handle oil spills of any size.

There’s oil under them ‘bergs…

Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Rob Huebert is senior research fellow at the Center for Military and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary and a board member of the Canadian Polar Commission, which is responsible for monitoring and disseminating knowledge of the polar regions.

He is not alone in suggesting that the time to act on oil spill preparedness should come sooner rather than later because oil and gas drilling, as well as shipping in the Arctic, will inevitably accelerate.

In addition to Russia, Huebert says, other Arctic nations — including Greenland, Norway, the United States, and Canada — are interested in developing energy resources in the Arctic, setting “these states on a collision course with the international environmental community.”

Recent oil spills such as Deepwater Horizon have provided engineers and biologists with valuable insights into the containment, cleanup, and disposal of spilled oil.

These spills have also spurred the U.S. Department of Interior to enact some of the most aggressive reforms to offshore oil and gas regulation and oversight in U.S. history.

But as Deepwater Horizon demonstrated, it takes a tremendous amount of resources to clean up a major spill.

At the height of the cleanup, 7,000 vessels, 125 aircraft, and 47,000 people were deployed from a host of easily accessible ports and bases across the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

And yet, several months after the oil well was finally capped, more than 100 millions gallons of oil — out of as many as 210 million spilled — was still unaccounted for.

Much of that missing oil is believed to have settled on the sea floor.

A spill on the scale of the Deepwater Horizon isn't going to happen anytime soon in the Arctic.

But experts say that mobilizing even a fraction of these resources in the region in an expeditious manner would be extremely difficult because there are few roads, runways, or ports in the Arctic; little expert manpower standing by to stage a response; and insufficient international protocols to orchestrate a cleanup if the oil crosses international boundaries.

Tracking the oil by satellite would also be difficult because of weather conditions and ice that may cover oil slicks.

Studies have shown that in most cases, no more than 20 per cent of oil spilled in the ocean can be recovered by mechanical means — those that do not involve the use of chemicals, which can be toxic to marine organisms.

In situ burning and chemical dispersants, therefore, would have to be relied upon heavily in the event of a spill in the Arctic, experts say.

University of Manitoba scientist David Barber heads up a Canadian research group with expertise in the detection, impacts, and mitigation of oil in sea ice.

He says there is very limited knowledge of how Arctic marine ecosystems will be affected by the presence, composition, and dispersion of oil, as well as chemicals used for cleanup, such as dispersants.

“Development of technologies that would be able to help detect oil in ice, and cold-adapted bioremediation technologies, are in their infancy,” he points out.

Barber and his group recently received $28 million in funding from the Canadian government to study ways of detecting oil in Arctic ice.

He says there are a number of variables in the Arctic that complicate containment and clean up efforts, with ice and cold weather topping the list.

Oil can become frozen in ice and drift long distances, and oil trapped under ice also breaks down more slowly because of reduced wave action.

Lower evaporation losses in cold climes also slow the breakdown of oil.

The long-lingering effects of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in southern Alaska demonstrated the difficulties of cleaning up oil spills in cold climes.

What worries scientists and environmentalists even more is a blowout that might take place toward the end of the summer drilling season.

“If a blowout were to occur and could not be contained before the winter freeze-up, it could spew oil uncontrollably for the seven or eight months of winter ice-cover, without the possibility of taking any steps during that time to control it,” Crowley says.

“The oil would bind with the newly formed ice, be carried far and wide by ocean currents, and released into new environments the following spring.”

This, Barber said, should cause people “to pause and reflect on the consequences of allowing oil and gas development in this region without the proper safeguards.”

Environmental groups are particularly concerned that Shell is being given permits for conditional drilling in the Arctic, considering that the company’s history of exploratory drilling has been fraught with problems, including the grounding of a drilling rig off the Alaska coast in late 2012.

Shell has made improvements in source control capping and containment since 2012, but experts with WWF and the Pew Charitable Trusts believe that Shell’s spill response capabilities, and those of U.S. agencies, still do not come close to resembling what an expert committee for the U.S. National Research Council recommended in 2014.

The report highlighted serious shortcomings and featured a long list of recommendations.

“There is still no backstop — no national regulation to ensure operators are prepared for the harsh conditions and remote location of the Arctic region,” says Marilyn Heiman, director of Pew’s US Arctic Project.

“That’s why we are pushing for [the] Interior [Department] to finalize strong regulations that will apply to all future drilling in the Arctic.”

The fact that Russia is ramping up activity in the Arctic was one of the concerns of the National Research Council committee.

If a spill or an accident were to happen on the Russian side of the border, the committee pointed out, oil could easily migrate into Alaskan waters.

The committee called on the U.S. Coast Guard to expand its bilateral agreement with Russia to include Arctic spill scenarios.

Crowley says the same international dispersion of oil could happen if a spill were to occur in Canada’s Beaufort Sea, where Imperial Oil Canada, Exxon Mobil, and BP have jointly filed an application to drill at least one well nearly a mile deep.

Crowley says that the barge that ended up in Russia is an example of what WWF-Canada has highlighted in an

oil spill modeling map of the Beaufort Sea.

The barge has followed roughly the same path along the Canadian, Alaskan, and Russian coasts as many of the 22 oil spill scenarios depicted on the WWF map.

“This also highlights the need for increased cooperation, both between industry and governments, and especially between the Arctic states who share these waters,” says Crowley.

Links :

.jpg)