The Thwaites ice shelf in West Antarctica is the floating extension of the Thwaites Glacier, which drains a large portion of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

The ice shelf is thinning due to melting by warm ocean water below.

The uniquely vulnerable West Antarctic Ice Sheet holds enough water to raise global sea levels by 5 meters.

But when that will happen—and how fast—is anything but settled.

In May 2014, NASA

announced at a press conference that a portion of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet appeared to have reached a point of irreversible retreat.

Glaciers flowing toward the sea at the periphery of the 2-kilometer-thick sheet of ice were losing ice faster than snowfall could replenish them, causing their edges to recede inland.

With that, the question was no longer whether the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would disappear, but when.

When those glaciers go, sea levels will rise by more than a meter, inundating land currently inhabited by

230 million people.

And that would be just the first act before the collapse of the entire ice sheet, which could raise seas

5 meters and redraw the world’s coastlines.

At the time, scientists assumed that the loss of those glaciers would unfold over centuries.

But in 2016, a bombshell study in

Nature concluded that crumbling ice cliffs could trigger a runaway process of retreat, dramatically hastening the timeline.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) took notice, establishing a sobering new worst-case scenario: By 2100, meltwater from Antarctica, Greenland, and mountain glaciers combined with the thermal expansion of seawater could raise global sea levels by over

2 meters.

And that would only be the beginning.

If

greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, seas would rise a staggering

15 meters by 2300.

However, not all scientists are convinced by the runaway scenario.

Thus, a tension has emerged over how long we have until West Antarctica’s huge glaciers vanish.

If their retreat unfolds over centuries, humanity may have time to adapt.

But if rapid destabilization begins in the coming decades through the controversial runaway process, the consequences could outpace our ability to respond.

Scientists warn that major population centers—New York City, New Orleans, Miami and Houston—may not be ready.

“We’ve definitely not ruled this out,” said

Karen Alley, a glaciologist at the University of Manitoba whose research supports the possibility of the runaway process.

“But I’m not ready to say it’s going to happen soon.

I’m also not going to say it can’t happen, either.”

For millennia, humanity has flourished along the shore, unaware that we were living in a geological fluke—an unusual spell of low seas.

The oceans will return, but how soon? What does the science say about how ice sheets retreat, and therefore, about the future of our ports, our homes, and the billions who live near the coast?

Grounded by the Sea

In 1978, John Mercer, an eccentric glaciologist at Ohio State University who allegedly conducted fieldwork nude, was among the first to

predict that global warming threatened the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

He based his theory on the ice sheet’s uniquely precarious relationship with the sea.

Bigger than Alaska and Texas combined, West Antarctica is split from the eastern half of the continent by the Transantarctic Mountains, whose peaks are buried to their chins in ice.

Unlike in East Antarctica (and Greenland), where most ice rests on land high above the water, in West Antarctica the ice sheet has settled into a bowl-shaped depression deep below sea level, with seawater lapping at its edges.

This makes West Antarctica’s ice sheet the most vulnerable to collapse.

A heaping dome of ice, the ice sheet flows outward under its own weight through tentacle-like glaciers.

But the glaciers don’t stop at the shoreline; instead, colossal floating plates of ice hundreds of meters thick extend over the sea.

These “ice shelves” float like giant rafts, tethered by drag forces and contact with underwater rises and ridges.

They buttress the glaciers against an inexorable gravitational draw toward the sea.

ILLUSTRATION: MARK BELAN/QUANTA MAGAZINE

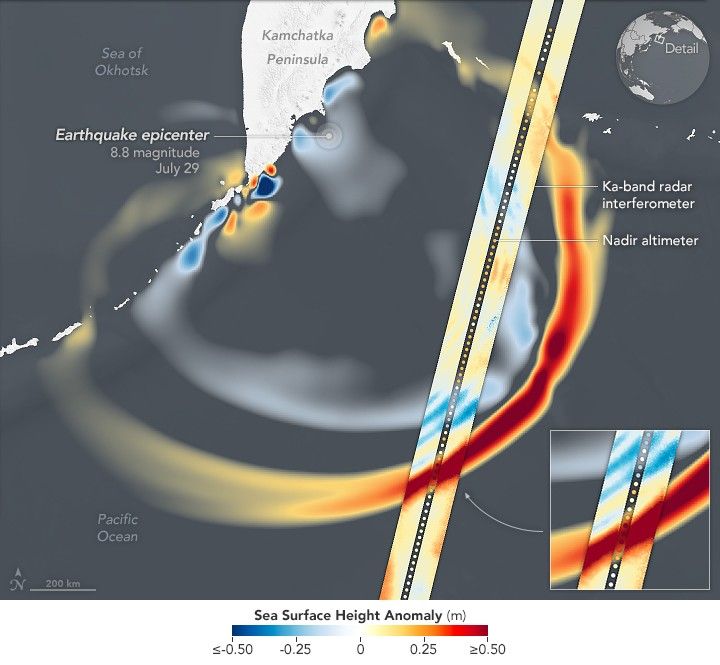

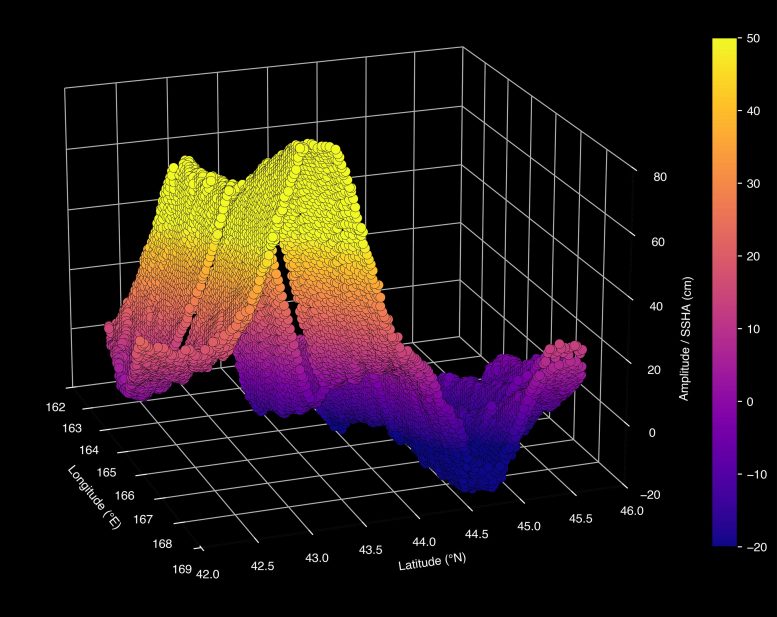

The critical frontline of the ice sheet’s vulnerability is the “grounding line,” where ice transitions from resting on the seafloor to floating as an ice shelf.

As the relatively warm sea works its way below the protective shelves, it thins them from below, shifting the grounding line inland.

The floating shelves fragment and break away.

The upstream glaciers, now without their buttressing support, flow faster toward the sea.

Meanwhile, seawater intrudes like an advancing army toward thicker ice, which rests on bedrock that slopes inward toward the bowl-like center of the continent.

“There’s a very serious message here,” said

Hilmar Gudmundsson, a glaciologist at Northumbria University: As the grounding line marches inland toward ever-thicker ice in a process called marine ice sheet instability, “you will have a very sharp increase in global sea level, and it will happen very quickly.”

In 2002, scientists got a live view of how that process may play out.

The

Larsen B ice shelf, a floating mass off the Antarctic Peninsula roughly the size of Rhode Island, broke apart in just over a month, stunning scientists.

Pooling surface meltwater had

forced open cracks—a process called hydrofracturing—which splintered the shelf, the only barrier for the glaciers behind it.

The glaciers began flowing seaward up to

eight times faster.

One of these, Crane Glacier, lost its cliff edge in a series of collapses over the course of 2003, causing it to shrink rapidly.

What if something similar happened to far larger glaciers on the coast of West Antarctica, like Thwaites and Pine Island?

In 2002, scientists watched with amazement as the Larsen B ice shelf collapsed in just over a month.

At the start of this series of NASA satellite images, pools of meltwater that contributed to the fracturing of the ice shelf are visible as parallel blue lines.

The shelf soon disintegrated into a blue-tinged mélange of slush and icebergs.

This ice debris field largely melted the following summer and began to drift away with the currents.

PHOTOGRAPH: NASA EARTH OBSERVATORY

In the years that followed, studies of ancient shorelines revealed a stunning sensitivity in the Earth system: It appeared that epochs only slightly warmer than today featured seas 6 to 9

meters above present-day levels.

In response, glaciologists

Robert DeConto and

David Pollard developed a bold new theory of ice sheet collapse.

They created a computer simulation based on Larsen B’s breakup and Greenland’s calving glaciers that was also calibrated to the geologic past—projecting future melt that matched expectations derived from ancient sea levels.

Their 2016

study outlined a scenario of almost unimaginably quick ice loss and sea-level rise.

In a process called marine ice cliff instability (MICI), cliffs taller than 90 meters at the edges of glaciers become unstable and collapse, exposing ever-thicker ice in a chain reaction that accelerates retreat.

The model suggested that ice from Antarctica alone—before any additions from Greenland, mountain glaciers or thermal expansion—could raise the seas by more than a meter by 2100.

In a

2021 update that incorporated additional factors into the simulations, DeConto and colleagues revised that estimate sharply downward, projecting less than 40 centimeters of sea-level rise by the century’s end under high-emission scenarios.

Yet even as the numbers have shifted, DeConto remains convinced of the MICI concept.

“It’s founded on super basic physical and glaciological principles that are pretty undeniable,” he said.

Mechanisms to Slow RetreatAfter the 2016 study, the scientific community set out to test whether towering ice cliffs really could undergo runaway collapse.

Many soon found reasons for doubt.

Few dispute the basic physics: If ice shelves like Larsen B collapse quickly and expose tall-enough cliffs on the glaciers behind them, those cliffs will indeed buckle under their own weight.

“There’s a reason why skyscrapers are only so tall,” said

Jeremy Bassis, a glaciologist and expert in fracture mechanics at the University of Michigan.

However, critics argue that runaway cliff collapse hasn’t been seen in nature, and there might be good reasons why not.

“Yes, ice breaks off if you expose tall cliffs, but you have two stabilizing factors,” said

Mathieu Morlighem, a glaciologist at Dartmouth College who led a 2024

study that identified these factors.

First, as newly exposed glacier cliffs topple, the ice behind stretches and thins.

As this happens, rapidly, “your ice cliff is going to be less of a tall cliff,” Morlighem said.

Second, the flowing glacier brings more ice forward to replace what breaks off, slowing the cliff’s inland retreat and making a chain reaction of cliff toppling less likely.

Another study challenging the MICI scenario noted that breaking ice also tends to form a mélange, a dense, jumbled slurry of icebergs and sea ice.

This frozen slurry can act as a retaining wall, at least temporarily

stabilizing the cliffs against collapse.

The bedrock beneath the ice might also be a key player.

“The solid Earth is having much bigger impacts on our understanding of sea-level change than we ever expected,” said

Frederick Richards, a geodynamicist at Imperial College London.

Scientists have long recognized that when glaciers melt, the land rebounds like a mattress relieved of weight.

But this rebound has been mostly dismissed as too sluggish to matter for several centuries.

Now, high-precision GPS and other geophysical data reveal rebound occurring over decades, even years.

Whether that’s good or bad depends on how quickly ice retreats.

If it goes at a modest clip, the bedrock lifts the ice, reducing the amount of water that can lap away at it.

But if retreat happens quickly enough through something like runaway cliff collapse, the Earth can’t keep up.

A 2024

study showed that the bedrock still rises, but in that scenario it pushes meltwater into the ocean.

“You’re actually getting more sea-level rise,” Richards said.

“You’re pushing all this water out of a bowl underneath West Antarctica and into the global ocean system.”

Earth’s restlessness also affects models of ancient sea-level rise.

In a 2023

study, Richards and colleagues found that Australia’s 3-million-year-old Pliocene shorelines had ridden the slow heave and sigh of Earth’s mantle, and that accounting for that vertical motion resulted in lower estimates for ancient sea levels.

This matters, according to Richards, because the revised record is a better match for more conservative ice retreat models.

“Hold on, guys,” he said.

“We have to be a little bit careful.

[Ancient] sea-level estimates might be overestimates, and therefore we might be overestimating how sensitive the ice sheets are.”

DeConto points to the Larsen B breakup and the crumbling of Greenland’s Jakobshavn Glacier as evidence to the contrary.

Once Larsen B stopped holding back the Crane Glacier, he says, ice began breaking away faster than the glacier could replenish it.

That is “really strong evidence that fracture can outpace flow.”

From Past to Future

“When I started my career, the question was whether Antarctica was growing or shrinking,” said

Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

The IPCC long held that the ice sheet would remain relatively stable through the 21st century, on the logic that rising temperatures would bring more snow, offsetting melt.

That assumption collapsed along with Larsen B in the early 2000s, and scientists soon came to a consensus that ice loss was well underway.

Satellite observations revealed that glaciers along the Amundsen Sea, including Pine Island and Thwaites, were flowing faster than in previous decades.

The ice sheet was not in balance.

By the time NASA called the 2014 press conference, it was clear that many of West Antarctica’s enormous glaciers had been retreating steadily since the 1990s.

The aftermath of Hurricane Florence in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina in 2018.

Worldwide, some 230 million people live less than a meter above sea level, and 1 billion people are within 10 meters of sea level.

CREDIT: NATIONAL GUARD/ALAMY

“It was the first time we had enough observations to say, hey, look, these grounding lines have been retreating year after year,” said Morlighem, a coauthor on one of the studies presented at the press conference.

This steady loss signaled that the glaciers would inevitably disappear.

“In theory, if we turn off melt, we can stop it,” he noted.

“But there’s absolutely zero chance we can do that.”

While the conversation has centered on how the sea will lap away at the ice shelves, some scientists are increasingly concerned about what’s happening up top, as warming air melts the ice sheet’s surface.

Nicholas Golledge, a glaciologist at Victoria University of Wellington, sees West Antarctica today as transitioning to the status of Greenland: Most of Greenland’s marine-vulnerable ice has already vanished, and surface melt dominates.

That process, Golledge believes, may soon play a bigger role in Antarctica than most models assume.

Pooling meltwater, for example, contributed to the Larsen B collapse.

As the water trickles into crevasses, it lubricates the bedrock and sediments below, making everything more slippery.

The Columbia University glaciologist

Jonny Kingslake says these processes are oversimplified or omitted in numerical simulations.

“If you ignore hydrology change, you are underestimating retreat,” he said.

Indeed, a 2020 study

found that meltwater trickling into Antarctica’s ice shelves could infiltrate cracks and force them open, a precursor to marine ice cliff instability that DeConto and colleagues envisioned.

Depending on future emissions, the IPCC now projects an average sea-level rise of half a meter to 1 meter by 2100, a total that includes all melt sources and the expansion of warming water.

The MICI process, if correct, could accelerate Antarctica’s contribution enough to double that overall rise.

“There’s deep uncertainty around some of these processes,” said

Robert Kopp, a climate scientist and science policy expert at Rutgers University.

“The one thing we do know is that the more carbon dioxide we put into the atmosphere, the greater the risk.”

In Bassis’ view, “Whether it’s with marine ice cliff instability or marine ice sheet instability, it’s a bit of a distraction.

By 2100, we will be talking about a coastline radically different than what I grew up with.”