1.2 miles: distance that seawater would penetrate inland in Cuba by 2100, according to scientists

10,000 : number of sanctions and fines handed down for illegal development along Cuba's coast

$2.5 billion: annual tourism revenue in Cuba

From Washington Post

After Cuban scientists studied the effects of climate change on this island’s 3,500 miles (5,630 kilometers) of coastline, their discoveries were so alarming that officials didn’t share the results with the public to avoid causing panic.

The scientists projected that rising sea levels would seriously damage 122 Cuban towns or even wipe them off the map.

Beaches would be submerged, they found, while freshwater sources would be tainted and croplands rendered infertile.

In all, seawater would penetrate up to 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) inland in low-lying areas, as oceans rose nearly three feet (85 centimeters) by 2100.

Climate change may be a matter of political debate on Capitol Hill, but for low-lying Cuba, those frightening calculations have spurred systemic action.

Cuba’s government has changed course on decades of haphazard coastal development, which threatens sand dunes and mangrove swamps that provide the best natural protection against rising seas.

In recent months, inspectors and demolition crews have begun fanning out across the island with plans to raze thousands of houses, restaurants, hotels and improvised docks in a race to restore much of the coast to something approaching its natural state.

“The government ... realized that for an island like Cuba, long and thin, protecting the coasts is a matter of national security,” said Jorge Alvarez, director of Cuba’s government-run Center for Environmental Control and Inspection.

At the same time, Cuba has had to take into account the needs of families living in endangered homes and a $2.5 billion-a-year tourism industry that is its No. 1 source of foreign income.

It’s a predicament challenging the entire Caribbean, where resorts and private homes often have popped up in many places without any forethought.

Enforcement of planning and environmental laws is also often spotty.

With its coastal towns and cities, the Caribbean is one of the regions most at risk from a changing climate.

Hundreds of villages are threatened by rising seas, and more frequent and stronger hurricanes have devastated agriculture in Haiti and elsewhere.

In Cuba, the report predicted sea levels would rise nearly three feet by century’s end.

“Different countries are vulnerable depending on a number of factors, the coastline and what coastal development looks like,” said Dan Whittle, Cuba program director for the New York-based nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund.

He said the Cuban study’s numbers seem consistent with other scientists’ forecasts for the region.

The Associated Press was given exclusive access to the report, but not permitted to keep a copy.

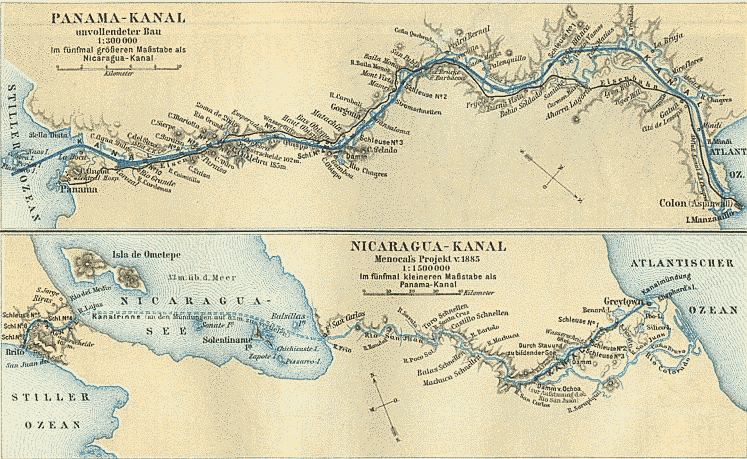

NGA chart #27084

Cuba’s preparations were on clear display on a recent morning tour of

Guanabo, a popular getaway for Havana residents known for its soft sand and gentle waves 15 miles (25 kilometers) east of the capital.

Where a military barracks had been demolished, a reintroduced sand-stabilizing creeper vine known as beach morning glory is reasserting itself on the dunes, one lavender blossom at a time.

The demolition nearby of a former swimming school was halted due to the lack of planning, with the building’s rubble left as it lay.

Now inspectors have to figure out how to fix the mess without doing further environmental damage.

Alvarez said the government has learned from such early mistakes and is proceeding more cautiously.

Officials also are also considering engineering solutions, and even determining whether it would be better to simply leave some buildings alone.

For three decades Guanabo resident Felix Rodriguez has lived the dream of any traveler to the Caribbean: waking up with waves softly lapping at the sand just steps away, a salty breeze blowing through the window and seagulls cawing as they glide through the crisp blue sky.

Now that paradise may be no more.

“The sea has been creeping ever closer,” said Rodriguez, a 63-year-old retiree, pointing to the water line steps from his apartment building.

“Thirty years ago it was 30 meters (33 yards) farther out.”

“We’d all like to live next to the sea, but it’s dangerous ... very dangerous,” Rodriguez said.

“When a hurricane comes, everyone here will just disappear.”

Cuban officials agree, and have notified him and 11 other families in the building that they will be relocated, though no date has been set.

Rodriguez and several other residents said they didn’t mind, given the danger.

Since 2000, Cuba has had a coastal protection law on the books that prohibits construction on top of sand and mandates a 130-foot-wide (40-meter) buffer zone from dunes.

Structures that predate the measure have been granted a stay of execution, but are not to be maintained and ultimately will be torn down once they’re uninhabitable.

Serious enforcement only began in earnest in recent months, as officials came armed with the risk assessment.

Some 10,000 sanctions and fines have been handed down for illegal development, according to Alvarez.

Demolitions have so far been limited to vacation rentals, hotel annexes, social clubs, military installations and other public buildings rather than private homes.

“Less strict measures have been taken with the people,” Alvarez said, acknowledging that relocating communities is tough in a country with a critical lack of adequate housing.

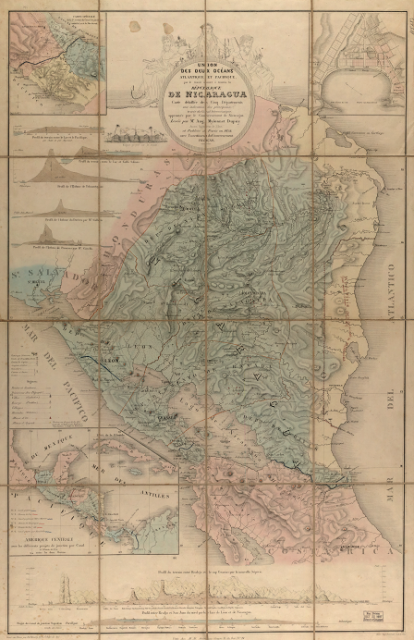

Varadero, situated on the Hicacos Peninsula,

between the Bay of Cárdenas and the Straits of Florida,

some 140 km east of Havana

(NGA chart)

One flashpoint is the powdery-white-sand resort of

Varadero, a two-hour’s drive east of the capital, where lucrative hotels attract hundreds of thousands of visitors each year from Canada, Europe and Latin America.

Some 900 coastal structures have been contributing to an average of about 4 feet (1.2 meters) of annual coastline erosion, according to geologist Adan Zuniga of Cuba’s Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research, a government body.

Building solid structures on top of dunes makes them more vulnerable to the waves.

“These are violent processes of erosion,” Zuniga said about regional development. “In many places the beaches are receding 16 feet (5 meters) a year.”

Varadero symbolizes Cuba’s dilemma: Tearing down seaside restaurants, picturesque pools and air-conditioned hotels threatens millions of dollars in yearly tourism revenue, but allowing them to stay puts at risk the very beaches that were the draws in the first place.

Cuban officials have tried to get around that choice by replenishing lost sand in Varadero, with plans to do the same next year at the Cayo Coco resort.

But beach replenishment is an expensive remedy that Cuba can little afford to carry out nationwide.

Zuniga said it costs $3 to $8 per cubic meter, and a single beach might contain up to 1 million cubic meters of sand.

The measure will still be necessary at Cayo Coco although the resort was developed with environmental mitigations such as keeping hotels behind the tree line and running a hydraulic system that keeps water circulating properly in an inland lagoon.

There are no publicly available figures on how many structures have been or will be razed across Cuba.

Alvarez and Zuniga said officials are evaluating problem buildings on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the needs of local economic development.

They say nothing is off-limits; even the emblematic Hotel Internacional, a four-story resort built in 1950 as a sibling to the Fontainebleau in Miami, has been doomed to demolition in Varadero at an unspecified date.

Other installations are gradually being moved inland, and government officials are applying stricter oversight on new construction, they said.

In May, authorities unveiled the near-completed Hotel Melia Marina Varadero and yacht club, which lies at a safe remove from the sea.

Cuba’s Communist government wields a unique advantage, one no other country in the region claims: The government and its subsidiaries control the island’s entire hotel stock, sometimes teaming with minority foreign partners on management.

Cuba’s military-run Gaviota Group alone controls more than three-dozen major hotels.

So when the government makes up its mind to tear down a hotel, it can do so without having to worry about fighting a lengthy court battle against a displaced owner.

On top of that, oversight of the coastal initiative happens at the highest level possible: Cuba’s ruling Council of State, headed by President Raul Castro.

“He is leading this battle,” Alvarez said of Castro.

Whittle said the island can learn some things from Costa Rica, where significant swaths of coastal and inland terrain have been protected even as tourism flourishes.

For Cuba, there’s a lot riding on striking the right balance.

“Will Cuba become a sustainable destination like Costa Rica?” Whittle asked.

“Or will it go the way of Cancun and much of the rest of the Caribbean that has essentially sacrificed natural areas, marine and coastal ecosystems for economic development in the short run?”