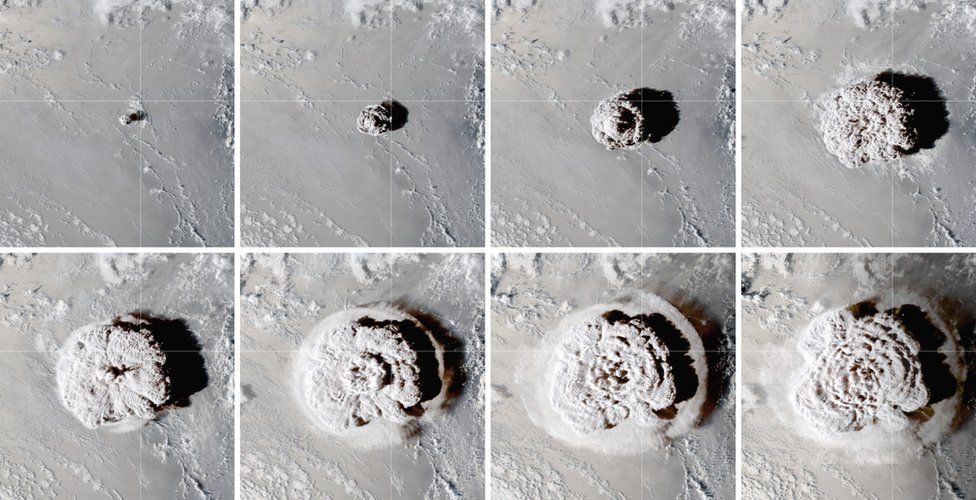

One year later, researchers are still marveling at the power of the

Hunga Tonga explosion—and wondering how to monitor hundreds of other

undersea volcanoes.

Last year, Larry Paxton was looking at the edge of space when he saw something he shouldn’t.

A physicist at Johns Hopkins University, Paxton uses satellite-based instruments that look down on the region of space just above the atmosphere.

They see in spectrums of light that we can’t, like the far ultraviolet, monitoring for things like odd space weather.

But in late January, his team observed something unusual on a scan: Part of the map had gone dark.

The rays of far UV light were being absorbed by molecules of some sort, resulting in a dim splotch roughly the size of Montana.

The source soon became clear: the Hunga Tonga volcano, which

had just erupted in the South Pacific.

Those molecules—enough water, Paxton’s team later determined, to fill 100 Olympic swimming pools—had been jettisoned skyward faster than the speed of sound by an explosion unlike anything previously recorded on Earth.

“This is an enormous amount of water to get injected that high,” says Paxton, who presented his research a few weeks ago at the American Geophysical Union.

“It’s an extraordinary thing.”

One year later, scientists studying virtually every facet of the Earth, from the mantle to the oceans to the ionosphere, have had a moment similar to Paxton’s, stunned by some superlative discovery generated by the Hunga eruption.

In recent months, scientists have observed

new vibrational waves that ricocheted around the globe, triggering tsunamis in distant ocean basins, and seen the highest concentration of

lightning ever recorded.

The newly cosmic water molecules represented the very top of an enormous plume

that filled the upper atmosphere with enough water to trap heat underneath, likely warming the Earth slightly for the next few years, according to Holger Vömel, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The January 15, 2022

explosion was obviously strange.

But now researchers are asking: Just how singular was it? The answer has implications for the hundreds of underwater volcanoes dotting the Earth’s oceans.

“The Hunga eruption highlights a new type of volcano, and new types of underwater threats,” says Shane Cronin, a volcanologist at the University of Auckland.

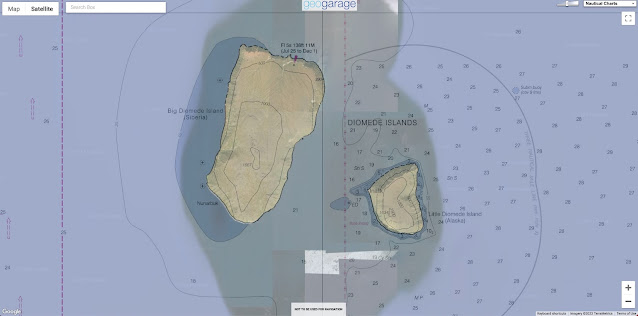

And yet only a handful of underwater volcanoes have been the site of extensive research.

Those include the Axial seamount, which lies a few hundred miles off the coast of Oregon and has been studied since the 1970s, and the long-active Kick ’em Jenny near the Caribbean nation of Grenada.

Both receive regular visits from research cruises and are covered with sensors that monitor for rumbles.

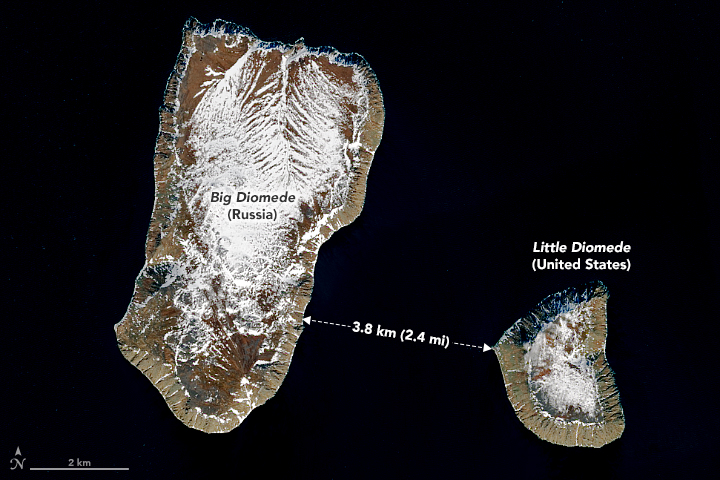

But many more are found in remote arcs of the Pacific, far from big cities or ports where research vessels make harbor.

Their closest neighbors are small island nations, like Tonga, that don’t have dedicated volcano-monitoring programs or much capacity to install seismic monitors.

That’s in part due to geographical problems.

Tonga, for example, is a line of islands, which isn’t great for triangulating the sources of seismic waves—and staffing and funds can be scarce in countries where the population is similar in size to a large US town.

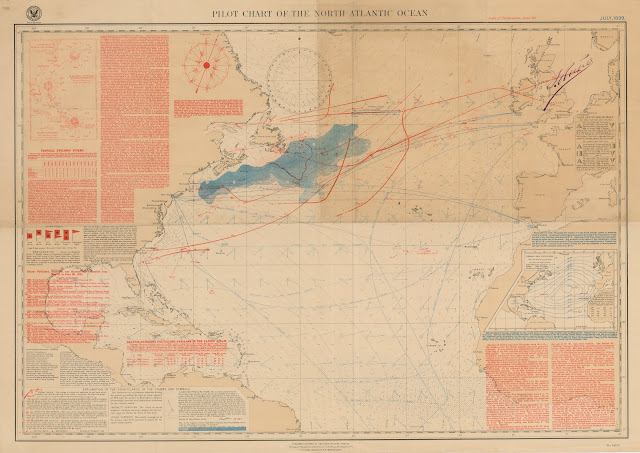

There are international options, like the US Geological Survey’s Seismic Monitoring Network, that offer global coverage for unusual geologic activity, but the stations are generally too few and far between to pick up the softer rumbles foretelling a coming undersea eruption, says Jake Lowenstern, director of the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program at USGS.

Most of those eruptions have no chance of matching the explosiveness of Hunga Tonga.

But the event awakened the world to the possibile activity of these volcanoes, says Sharon Walker, an oceanographer at the Pacific Marine Environment Laboratory.

“While events like this don’t happen very often, my feeling is that we do not want them to happen on our watch,” she says.

It’s clear that Hunga involved an unusually explosive recipe that may not be easily replicated.

For about a month, the eruption had progressed as expected—moderately violent, with gas and ash, but manageable.

Then everything went sideways.

That appears to be the result of at least two factors, Cronin says.

One was the mixing of sources of magma with slightly different chemical compositions down below.

As these interacted, they produced gasses, expanding the volume of the magma within the confines of the rock.

Under tremendous pressure, the rocks above began to crack, allowing the cold seawater to seep in.

“The seawater added the extra spice, if you like,” Cronin says.

A massive explosion ensued—two of them actually—which blew trillions of tons of material straight out through the top of the caldera, some of it apparently all the way to space.

Both of those explosions produced big tsunamis.

But the biggest wave came later—potentially caused, Cronin thinks, by water flooding into the kilometer-deep hole suddenly dug out of the seafloor.

“That’s something really new for us,” he says—a new type of threat to consider elsewhere.

Previously, scientists thought that this kind of volcano could only really produce a big tsunami if a side of a caldera collapsed.

The bottom line, he says, is that submarine volcanoes are more diverse, and in some cases more capable of extreme behavior, than anyone thought.

But the process of piecing the eruption together has also highlighted the challenges of studying submarine volcanoes.

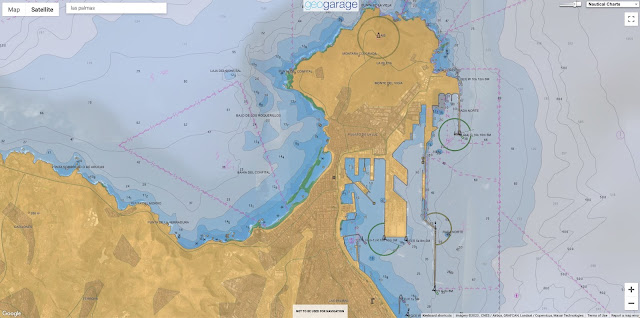

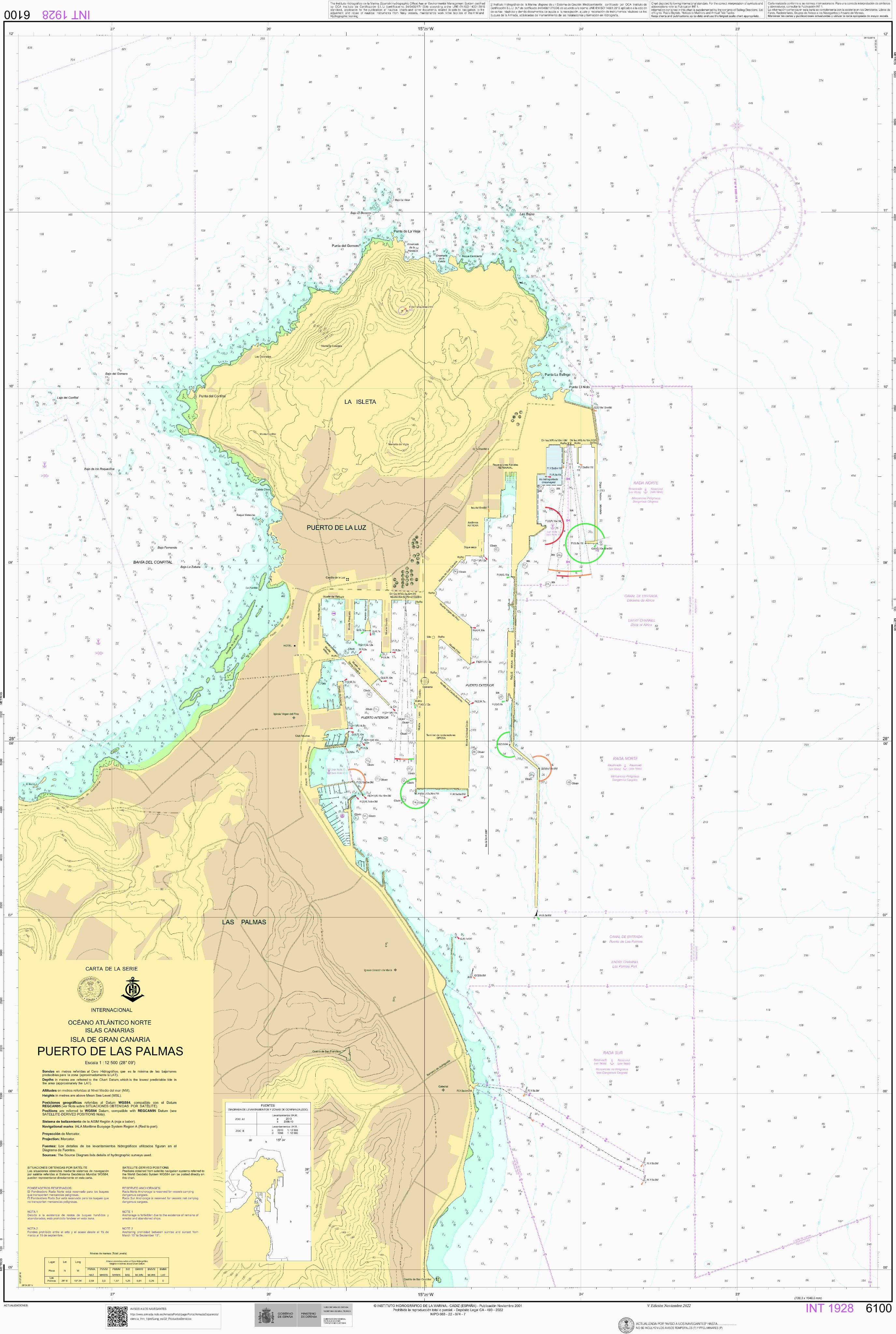

A typical mapping expedition will involve a large, fully crewed research vessel, equipped with multibeam sonar that maps the seafloor for changes and a battery of water sampling instruments that search for chemical signs of ongoing activity.

But taking a boat over a potentially active caldera is risky—not so much because the volcano might blow, but because the gas bubbles burbling up might cause a ship to sink.

In Tonga, researchers solved that problem with smaller ships and an autonomous vessel.

Even Tonga, which has been visited four times in the past year due to an influx of research funding to groups studying the eruption, isn’t likely to get another big crewed mission in the next few years, Cronin says.

The cost is just so high.

It would likely take decades to survey every volcano in detail, even just those in the Tongan arc.

This is a shame, Walker says, because those kinds of expeditions are one of the few ways scientists get close enough to actually see how volcanoes are behaving.

An ideal scenario would involve more funding for those missions, as well as investment in improving new technology, like the autonomous vessels, which can be tricky to operate in the treacherous open ocean.

Without them, scientists are stuck watching from a distance.

This is hard to do when you’re trying to observe underwater events—but not impossible.

Satellite technology can spot objects known as pumice rafts—sheets of buoyant volcanic rock that bob on the water’s surface—as well as algal blooms, which are nurtured by the minerals released by volcanoes.

And the USGS, as well as counterparts in Australia, are in the process of installing a network of sensors around Tonga that can better detect volcanic activity, combining seismic stations with sound sensors and webcams that watch for active explosions.

Ensuring it stays up and running will be a challenge, Lowenstern says—a matter of keeping the systems connected to data and to power sources and ensuring Tonga can staff the facilities.

He adds that Tonga is just one of many Pacific nations that could use the help.

But it’s a start.

One of the benefits of studying the Hunga volcano so closely is that researchers have now identified new volcanic features to watch out for.

Over the next few years, Cronin foresees a process of identifying which volcanoes require more attention.

On their final Hunga voyage of 2022, Cronin’s team made use of the time on the ship to visit two other submarine volcanoes in the area, including one about 100 miles north with a mesa-like topography that resembles Hunga before its eruption.

The maps will be a baseline for future surveys that manage to get out on the water, a way for researchers to figure out how much action is happening underneath sea and rock.

So far, Cronin reports, the ocean is quiet.