The first major

military conflict in the SCS happened between China and Vietnam in 1974, after which China established its claims over the Paracel Islands.

The second major confrontation occurred in 1988 between the two countries over the control of the Fiery Cross Reef, leading to Vietnam losing three naval vessels and 72 troops.

This was followed by China occupying Mischief Island, which falls within the Philippines’ EEZ.

However, unlike in the South China Sea, China and Japan have not gone to war or engaged in direct military confrontation with each other over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands after the two treaties.

Another source of the disputes stems from competition over natural resources in both regions.

In the case of the East China Sea, the competition began when the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (UNECAFE) announced that these islands were rich in

hydrocarbon resources located under the continental shelf between Taiwan and Japan.

This resulted in the escalation of competition and conflict between the claimants to exploit these resources since the countries saw this as an opportunity to reduce their dependency on Arab states for oil and also transition to natural gas because they believed it would be ‘cheap and useful.’ Fish is another resource of contestation as both China and Japan, along with South Korea, regularly exploit the region for fish and algae.

This is because the ECS yields the highest catch of fish at slightly over 3.8 million tonnes, which serves as a crucial food supply throughout the region since fish serves 22.3% of public diets across East Asia.

Similarly, the South China Sea is also a hub of marine and hydrocarbon resources.

For instance, the area serves as fishing grounds for Chinese fishermen and people living near the sea, with China becoming one of the largest fishing industries in the world since 2010, owing to the abundance of marine resources in the region.

The fishing industry in China not only contributes significantly to national economy but also lets China play an important role as the ‘biggest exporter of aquatic products in the world.’ Besides marine resources, the region is also rich in energy resources, with the US Geological Survey estimating in 2012 that the entire South China Sea contains around 12 billion barrels of oil and 1900 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

Thus, regarding marine and hydrocarbon resources, the SCS and the ECS serve similar goals for China.

Beijing thus wants full sovereignty over th region to

exploit its resources to their fullest potential.

The third reason for China’s ongoing dispute over the islands is historical tensions and modern power struggles.

Modern Sino-Japanese relations have mainly been antagonistic and influenced by a history of colonialism and competition.

China had been a target of Japan’s imperialist ambitions but has now evolved to overtake Japan’s role as a global economic powerhouse.

Therefore, the attempts to

‘recover’ territories in the ECS become a part of a larger programme of returning the country’s position as a ‘regional hegemon.’ For nationalists in China, the material considerations of the dispute (control of the EEZs and the continental shelves of the islands) become secondary to the historical aspect of the dispute.

Similar to the ECS dispute, the origins of the claims of China’s assertion of sovereignty over the entire island chains of the South China Sea also pertain to its ‘

historic rights.’ China, like in the case of the East China Sea, has always perceived the SCS as their historical waters dating back to the past practices of navigation and trade during the Qing and Han dynasties.

The past colonial powers’ lack of general interest in solving the delimitation issues has given China a chance to put forth its historical rights façade to challenge the legitimacy of international law.

China also considers the SCS part of its ‘lost territories, ‘ which echoes its claims in the ECS.

The fourth reason for the disputes is strategic.

In terms of strategic significance, the ECS serves as a vital area for all the claimants, including the US.

In the north of the ECS is the entrance to the Sea of Japan, while in the south, there is Taiwan, which serves as a contested area between the US and China.

China also perceives Japan’s

‘assertive behaviour‘ in the ECS disputes as an attempt to ‘contain China’ just like the US, resulting in increasing insecurity leading to China’s assertive power positioning in its claims.

Therefore, China believes that acquiring the islands will help it successfully close its security gaps.

The Diaoyu islands can become a unique frontier to safeguard China from Japan and the US.

For instance, Japanese military experts claim that China can use the islands to establish missile bases, radar systems, and submarine bases, undoubtedly increasing China’s security and military presence in the region.

The South China Sea, just like the East China Sea region, is also significant to China strategically.

The SCS is a crucial SLOC that connects the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean and forms the lifeline of global commerce of goods and energy shipments to China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia.

If China controls the SCS, it would guarantee its security in distant waters.

Moreover, China can expand its maritime navigation, which could challenge US maritime dominance and power projection in East Asia.

Another commonality between the two regions pertains to maritime boundaries.

Both raise the question of

‘how and where’ a maritime boundary can be drawn.

In ECS, China’s maritime boundary that runs along its continental shelf ends at the Okinawa Trough.

Japan’s maritime boundary is drawn halfway between the Ryukyu Islands and the Chinese mainland.

Similarly, in the SCS, China draws its maritime boundary based on the nine-dash-line that it first pronounced in 1947 and later submitted to the UN Commission on the Continental Shelf in 2009.

However, China has never articulated its nine-dash-line’s precise latitudinal and longitudinal location.

Therefore, all other claimant countries in the region assert no legal basis for this line under the UNCLOS.

However, both disputes also have quite a few differences.

Firstly, certain SCS disputes regarding maritime boundaries have been submitted to international arbitration.

For instance, the Philippines submitted a Memorial to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague in March 2014 seeking to declare China’s nine-dash-line as

‘illegal and invalid’ and to get clarification on whether specific land features in the SCSC are ‘rocks, islands, or low-tide elevations.’ However, China has refused to participate in the case by stating that the PCA has no jurisdiction over the dispute, even though the Tribal ruled that there was no legal basis for China’s claims due to a lack of historical claims.

However, in the ESC, although Japan expressed an interest in international adjudication with China to resolve the dispute, particularly by the Democratic Party of Japan, the successive Shinzo Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party has generally refused to acknowledge the dispute, thereby preventing any international adjudication.

Secondly, while the South China Sea dispute is multilateral, the East China Sea dispute is bilateral.

Since multiple countries have overlapping claims over the

Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands in the SCS, these parties (excluding China) have taken diplomatic steps to resolve the disputes, such as the non-binding Declaration of the Code of Conduct of the South China Sea drafted in 2002, or the Philippines trying to enlist the ASEAN nations to address the dispute formally.

However, China has always scorned drafting a binding Code.

On the contrary, the ESC sovereignty claims over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands are limited to China and Japan.

Although Taiwan shares China’s claims, it has not been a part of China’s attempts to promote sovereignty over the Isles, mainly because China does not consider Taiwan a separate country.

Furthermore, compared to the South China Sea claimants, Japan is a more formidable military opponent to China.

This is because the main claimants of the SCS have significantly less military presence or modernization capabilities than China.

Vietnam only has a ‘respectable’ military force, while the Philippines’ armed forces are even less impressive in numbers than Vietnam.

By comparison, Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) consists of nearly 47,000 personnel and an equally impressive air force.

Its JCG (Japan Coast Guard) has been modernizing and building its capabilities for the long-term defence of the islets.

Japan’s military and coast guard forces pose a much more significant threat to the Chinese PLAN (PLA-Navy) than Vietnam or the Philippines.

However, the most crucial part of Japan’s military capabilities is the support of the US military.

Washington has been fully supporting Japan’s

‘valid and legal’ administration over the Senkaku islands, and any attempts by China to acquire the Diaoyu Islands would mean direct confrontation with Japan’s modern navy, air force, coast guard, and the US military.

In contrast, even though the Philippines is a US ally, its relationship with the latter is farther away than that of the US and Japan.

Moreover, as compared to Japan, wherein the US has its military forces stationed throughout the country and prepared for a Sino-Japan conflict, there is a lack of permanent and imposing US military presence on Filipino shores and therefore, its alliance with the US is less threatening to Beijing as compared to Tokyo.

Therefore, it can be observed that China’s unending appetite for territories in the South China Sea and the East China Sea stems from nationalistic beliefs of ‘historical injustices,’ material gains, strategic requirements and national security.

Empires have waged wars for much less.

As a state that considers its national security, economic prosperity and global hegemony as pertinent, it will not be wrong to presume that its expansionist tendencies towards its “historic territories” are far from over.

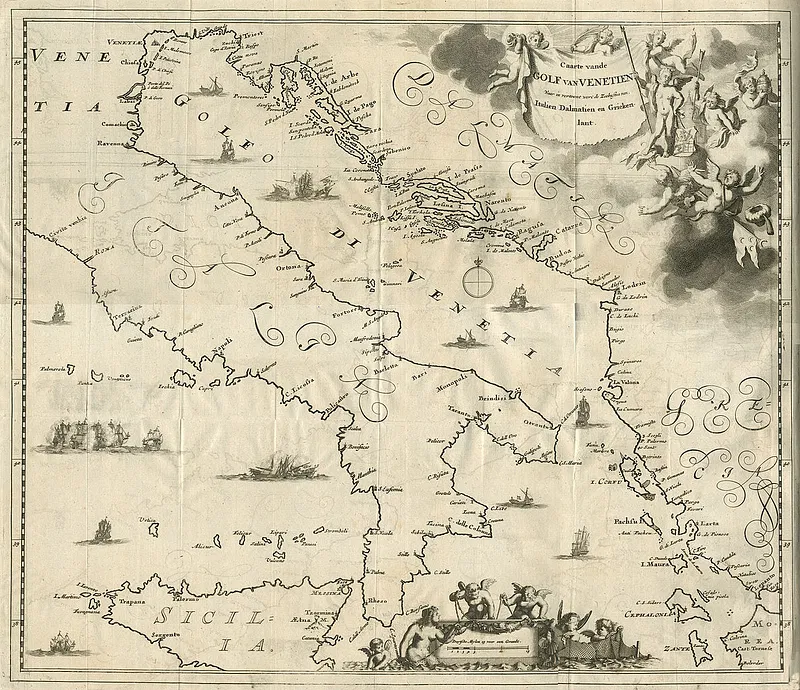

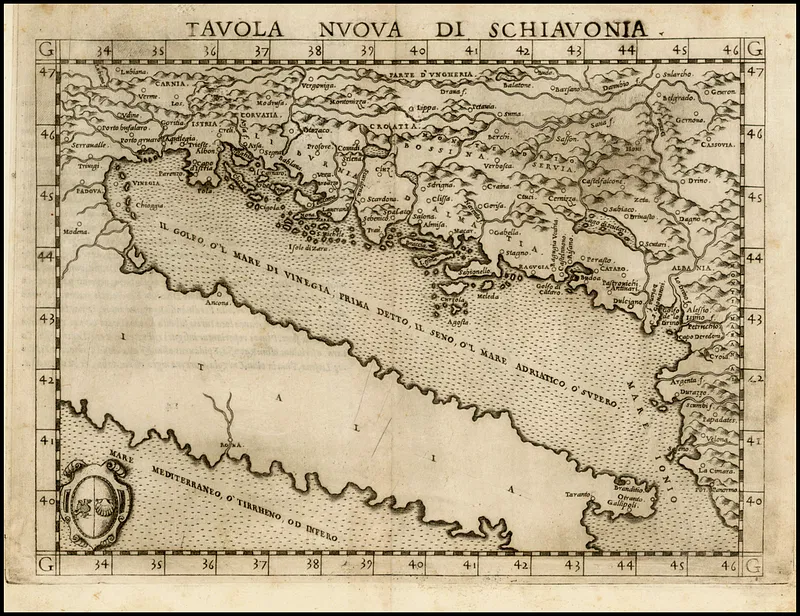

The debate over the name Adriatic Sea has been settled (at least for now), but it is a reminder of how countries often want particular names for bodies of land or water that show connections with their states.

The debate over the name Adriatic Sea has been settled (at least for now), but it is a reminder of how countries often want particular names for bodies of land or water that show connections with their states.

IMAGE SOURCE, CPL PHIL DYE RAF / CROWN COPYRIGHT

IMAGE SOURCE, CPL PHIL DYE RAF / CROWN COPYRIGHT