The energy transition is driving demand for resources that deepsea mining may be able to extract.

Saturday, October 7, 2023

Friday, October 6, 2023

Tonga eruption caused fastest ever underwater flow

From NIWA

NIWA and the UK’s National Oceanography Centre (NOC) say that the flows travelled at speeds of up to 122km/hour – up to 50% faster than any other recorded.

This new analysis, made possible by the NIWA-Nippon Foundation Tonga Eruption Seabed Mapping Project (TESMaP), comes after earlier results showed the eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai remobilised a staggering 10km3 of material from the seafloor.

As material from the volcanic eruption collapsed into the ocean, this triggered a huge surge of rock, ash, and gas that caused extensive damage to Tonga’s underwater telecommunication cables some 80km away.

Dr Emily Lane is NIWA’s Principal Scientist for Natural Hazards and is a co-author on the paper. She said the timings and locations of the damage to two subsea cables allowed them to determine the speeds of flows.

“Just a few months after the eruption, our team set sail to find out what caused it and what the impacts were. Surveys showed that Tonga’s domestic cable was buried under 30m of material, which we sampled and confirmed as containing deposits formed by a powerful seafloor flow triggered by the eruption.

“What’s impressive is that Tonga’s international cable lies in a seafloor valley south of the volcano, meaning the flow had enough power to go uphill over huge ridges, and then back down again,” said Dr Lane.

Kevin Mackay is a NIWA marine geologist and voyage leader of TESMaP. He says that this is just another record ticked off the list for this astonishing event.

“The seafloor flows were one of the big unknowns from this eruption – with it being an underwater volcano, it’s something you rarely get to study just after the fact. With atmospheric pressure waves circling the globe multiple times, and it being the largest atmospheric explosion on Earth in over 100 years, this just adds to that impressive list,” said Mr Mackay.

Dr Isobel Yeo is a volcanologist at the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and joint-lead scientist on the paper. She said this work is helping us to better understand the hazards of submerged volcanoes worldwide.

“A huge number of the world’s volcanoes lie under the ocean, yet only a handful of those are monitored. As a result, the risk posed to coastal communities and critical infrastructure remains poorly understood, and more monitoring is urgently needed,” said Dr Yeo.

“The seafloor flows were one of the big unknowns from this eruption – with it being an underwater volcano, it’s something you rarely get to study just after the fact. With atmospheric pressure waves circling the globe multiple times, and it being the largest atmospheric explosion on Earth in over 100 years, this just adds to that impressive list,” said Mr Mackay.

Dr Isobel Yeo is a volcanologist at the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and joint-lead scientist on the paper. She said this work is helping us to better understand the hazards of submerged volcanoes worldwide.

“A huge number of the world’s volcanoes lie under the ocean, yet only a handful of those are monitored. As a result, the risk posed to coastal communities and critical infrastructure remains poorly understood, and more monitoring is urgently needed,” said Dr Yeo.

Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha'apai: The highest eruption column ever recorded

image : Tonga Geological Services

image : Tonga Geological Services

Dr Mike Clare a geohazards researcher, also at NOC, said “Findings from this important study not only improve our understanding of one of the largest events on our planet, but are already being used by the subsea cable industry to design more resilient communications networks in volcanically active regions. Subsea cables are a critical part of all of our lives, so making sure global connections stay secure is important”.

The paper was part of a joint international project including NIWA, The Nippon Foundation, and the Natural Environment Research Council in collaboration with 13 partners from Tonga, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, USA, and the UK.

The paper was part of a joint international project including NIWA, The Nippon Foundation, and the Natural Environment Research Council in collaboration with 13 partners from Tonga, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, USA, and the UK.

Links :

Thursday, October 5, 2023

Geologist Marie Tharp mapped the ocean floor and helped solve one of science's biggest controversies

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the estate of Marie Tharp

From Business Insider by Jenny McGrath

Until the 1950s, scientists didn't have a clear understanding of what the seafloor looked like.

Geologist Marie Tharp turned years of data into easily digestible maps.

She also discovered the Mid-Atlantic rift, which contributed evidence to the plate tectonics theory.

Why do Earth's continents look like they fit together?

In the early 20th century, this was one of geology's greatest scientific mysteries and part of the solution lay at the bottom of the ocean.

Back then, no one knew what the ocean floor looked like — until one woman used her many talents to find out.

When she reflected on her life, geologist Marie Tharp recollected being able to fill in the blanks of the ocean floor, which she saw as a fascinating jigsaw puzzle.

She pinpointed mountains, volcanoes, and canyons that lurked under oceans, much like they do above sea level.

"It was a once-in-a-lifetime — a once-in-the-history-of-the-world — opportunity for anyone, but especially for a woman in the 1940s," Tharp wrote.

A geologist with Columbia University's Lamont Geological Laboratory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory), Tharp took sheets and sheets of depth readings and turned them into incredible maps.

Her maps not only helped her see the ocean floorin a whole new way, but they also helped change the way geologists and oceanographers thought about the Earth.

When continental drift was a controversy

When Tharp was still in elementary school, some scientists were tearing apart Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift.

A German meteorologist and astronomer, Wegener first presented his ideas in 1912.

Like others, he'd noticed that the continents looked as if they had once fit together.

Even though oceans separated them, their rock layers matched.

"It is just as if we were to refit the torn pieces of a newspaper by matching their edges," Wegener wrote in "The Origin of Continents and Oceans."

If he was correct, moving continents would explain many puzzling mysteries, like why Australian marsupials were more similar to South American animals than those in closer Asian countries.

Wegener's theory gained support, but many US scientists found it implausible.

One influential geologist, Bailey Willis, called it a "fairy tale." Instead, Willis stuck with his own theory that there had once been land bridges between the continents that had since sunk.

By the time Tharp enrolled in a two-year geology program at the University of Michigan in 1943, her instructors likely didn't advocate for Wegener's theory.

There wasn't yet "any satisfactory unifying hypothesis that could explain the main features and processes at the Earth's surface," geologist Bettie Higgs wrote of Tharp's education.

Studying the ocean from land

When Tharp arrived at Columbia University for a job with Maurice Ewing at Lamont, she joined a group of about two dozen men and women on the geophysics team in 1948.

The other women were mostly bookkeepers, assistants, or human calculators doing mathematical work.

Like many of her male colleagues, Tharp had a graduate degree in geology.

But she wasn't allowed on research vessels.

Some sailors still believed it was "unlucky" to have a woman aboard unless they were passengers.

In 1956, graduate student Roberta Eike lost her fellowship after sneaking aboard a ship in Massachusetts.

Tharp didn't sail on a mission until 1968.

Instead, Tharp spent much of her time assisting the men with calculations and diagrams.

After about three years, she nearly quit.

Whether she was overworked or frustrated at working on others' projects instead of her own isn't clear.

But when she came back, she embarked on a partnership that changed the trajectory of her career.

Back then, no one knew what the ocean floor looked like — until one woman used her many talents to find out.

When she reflected on her life, geologist Marie Tharp recollected being able to fill in the blanks of the ocean floor, which she saw as a fascinating jigsaw puzzle.

She pinpointed mountains, volcanoes, and canyons that lurked under oceans, much like they do above sea level.

"It was a once-in-a-lifetime — a once-in-the-history-of-the-world — opportunity for anyone, but especially for a woman in the 1940s," Tharp wrote.

A geologist with Columbia University's Lamont Geological Laboratory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory), Tharp took sheets and sheets of depth readings and turned them into incredible maps.

Her maps not only helped her see the ocean floorin a whole new way, but they also helped change the way geologists and oceanographers thought about the Earth.

When continental drift was a controversy

When Tharp was still in elementary school, some scientists were tearing apart Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift.

A German meteorologist and astronomer, Wegener first presented his ideas in 1912.

Like others, he'd noticed that the continents looked as if they had once fit together.

Even though oceans separated them, their rock layers matched.

"It is just as if we were to refit the torn pieces of a newspaper by matching their edges," Wegener wrote in "The Origin of Continents and Oceans."

If he was correct, moving continents would explain many puzzling mysteries, like why Australian marsupials were more similar to South American animals than those in closer Asian countries.

Wegener's theory gained support, but many US scientists found it implausible.

One influential geologist, Bailey Willis, called it a "fairy tale." Instead, Willis stuck with his own theory that there had once been land bridges between the continents that had since sunk.

By the time Tharp enrolled in a two-year geology program at the University of Michigan in 1943, her instructors likely didn't advocate for Wegener's theory.

There wasn't yet "any satisfactory unifying hypothesis that could explain the main features and processes at the Earth's surface," geologist Bettie Higgs wrote of Tharp's education.

Studying the ocean from land

When Tharp arrived at Columbia University for a job with Maurice Ewing at Lamont, she joined a group of about two dozen men and women on the geophysics team in 1948.

The other women were mostly bookkeepers, assistants, or human calculators doing mathematical work.

Like many of her male colleagues, Tharp had a graduate degree in geology.

But she wasn't allowed on research vessels.

Some sailors still believed it was "unlucky" to have a woman aboard unless they were passengers.

In 1956, graduate student Roberta Eike lost her fellowship after sneaking aboard a ship in Massachusetts.

Tharp didn't sail on a mission until 1968.

Instead, Tharp spent much of her time assisting the men with calculations and diagrams.

After about three years, she nearly quit.

Whether she was overworked or frustrated at working on others' projects instead of her own isn't clear.

But when she came back, she embarked on a partnership that changed the trajectory of her career.

Mapping the seafloor

By the early 1950s, echo sounders and precision depth recorders (PDRs) allowed scientists to continuously record seafloor depths, giving them a more complete picture than they'd ever had before.

The only problem was they produced loads of data.

Bruce Heezen, who started at Lamont around the same time as Tharp, handed it off to her in 1952.

There were long rolls of paper containing lines that rose and dipped, depending on how long it took the echo sounders' electronic ping to travel from the seafloor to the ship.

By the early 1950s, echo sounders and precision depth recorders (PDRs) allowed scientists to continuously record seafloor depths, giving them a more complete picture than they'd ever had before.

The only problem was they produced loads of data.

Bruce Heezen, who started at Lamont around the same time as Tharp, handed it off to her in 1952.

There were long rolls of paper containing lines that rose and dipped, depending on how long it took the echo sounders' electronic ping to travel from the seafloor to the ship.

Frank Albert Charles Burke/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

It was Tharp's job to translate 3,000 feet of paper and undulating lines into a map containing all the data from the various ships.

To do so, she had to compile snippets from different trips to get a continuous line from coast to coast.

And she had to do that up and down the continents, from Nova Scotia, Massachusetts, France, and the Strait of Gibraltar.

The result "looked like a spider's web," Tharp said, with lines resembling telephone wires spanning the Atlantic Ocean.

After weeks of looking at the data and plotting the lines, Tharp had noticed a pattern.

She had about half a dozen lines running across the ocean, and many had a v-shaped dip in a similar spot, right on top of an underwater mountain chain, the Mid-Atlantic Rift.

It looked like a rift.

But it couldn't be, Heezen told her, because that would be too much like continental drift.

He and "almost everyone else at Lamont, and in the United States, thought continental drift was impossible," according to Tharp.

It would take Heezen months to accept what he'd dismissed as Tharp's "girl talk."

The ups and downs at the bottom of the sea

In the meantime, Tharp and Heezen decided to use physiographic diagrams to capture what they were seeing in the data.

If the echo sounder recorded a large mountain, Tharp would make it appear tall next to shorter mounds.

In spots where ships hadn't recorded depth information, Tharp made educated deductions.

Shading and closely spaced lines gave an illusion of depth, making pointy peaks and flat sea mounts seem to rise off the page.

Amateurs and experts alike could easily get a sense of the underwater topography from Tharp's map.

"But we also had an ulterior motive," Tharp wrote.

"Detailed contour maps of the ocean floor were classified by the US Navy, so the physiographic diagrams gave us a way to publish our data."

Heezen had graduate student Howard Foster placing dots at the latitudes and longitudes of tens of thousands of earthquake epicenters on another map.

When Fosters' map was laid on top of the Tharp's diagram, the quakes snaked along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where she'd found the rift.

In the meantime, Tharp and Heezen decided to use physiographic diagrams to capture what they were seeing in the data.

If the echo sounder recorded a large mountain, Tharp would make it appear tall next to shorter mounds.

In spots where ships hadn't recorded depth information, Tharp made educated deductions.

Shading and closely spaced lines gave an illusion of depth, making pointy peaks and flat sea mounts seem to rise off the page.

Amateurs and experts alike could easily get a sense of the underwater topography from Tharp's map.

"But we also had an ulterior motive," Tharp wrote.

"Detailed contour maps of the ocean floor were classified by the US Navy, so the physiographic diagrams gave us a way to publish our data."

Heezen had graduate student Howard Foster placing dots at the latitudes and longitudes of tens of thousands of earthquake epicenters on another map.

When Fosters' map was laid on top of the Tharp's diagram, the quakes snaked along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where she'd found the rift.

The mid-ocean ridge traverses the globe.

USGS

USGS

Tharp was then able to use other seismic data to extend the ridge into the Indian Ocean and the East African Rift Valley.

What Heezen would later call a "monstrous scar" split the globe into pieces and the theory of continental drift now seemed undeniable.

A geological rift

In 1956, Heezen and Ewing, the head of the Lamont lab, published a paper noting a ridge covering about 40,000 miles of the ocean's floor, without crediting Tharp.

Two years later, at the 1959 International Oceanographic Conference, Heezen presented on continental drift and the rift.

By this time, other researchers in several fields were accumulating evidence that aligned with Wegener's theory.

Proof of Tharp's rift came from an unexpected source.

At the conference, underwater explorer Jacques Cousteau showed a video he'd filmed of the rift valley with an underwater camera.

In 1956, Heezen and Ewing, the head of the Lamont lab, published a paper noting a ridge covering about 40,000 miles of the ocean's floor, without crediting Tharp.

Two years later, at the 1959 International Oceanographic Conference, Heezen presented on continental drift and the rift.

By this time, other researchers in several fields were accumulating evidence that aligned with Wegener's theory.

Proof of Tharp's rift came from an unexpected source.

At the conference, underwater explorer Jacques Cousteau showed a video he'd filmed of the rift valley with an underwater camera.

ABC Photo Archives/Disney General Entertainment Content via Getty Images

Originally, Cousteau had planned to prove Tharp and Heezen wrong.

Instead, the footage "helped a lot of people believe in our rift valley," Tharp said.

Over the next decade, scientists in an array of fields contributed to the theory of plate tectonics with new explanations of everything from seafloor faults to the formation of the Earth's crust.

Marie Tharp's legacy

Tharp and Heezen continued to collaborate until his death in 1977.

Their final project together was the World Ocean Floor Map.

They recruited artist Heinrich Berann, who had worked with them on many maps for National Geographic, to paint it.

The map depicts the mid-ocean ridge zigzagging its way around the world.

It looks like if you ran your fingers over the paper, you'd be able to feel where it rises and falls.

Marie Tharp Maps, LLC

After Heezen's death, organizations that had hired him and Tharp to work on projects reassigned them.

A few years later, she was asked to retire from Lamont.

It's not clear why, and Tharp biographer Hali Felt noted that at 63 she wasn't "the oldest person there by any means."

Tharp continued working on her own projects and started a cartography business.

She protected and promoted Heezen's legacy, but she also "demanded fair recognition for work that was hers," according to Higgs.

Her contributions to oceanography and geology gained recognition with several awards, including the National Geographic Society's Hubbard Medal and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Mary Sears Woman Pioneer in Oceanography Award.

In 1997, the Library of Congress included some of Tharp's maps in an exhibition displaying items from Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Edison, and George Washington.

Tharp died in 2006.

Over 70 years since she watched her colleagues head off in ships she wasn't allowed to sail on, the US Navy announced it was renaming a research vessel in her honor, the USNS Marie Tharp.

Links :

Wednesday, October 4, 2023

Russian ENC (Northern part)

Info from Primar, RENC distributor (04.10.2023) :

"Due to circumstances outside of PRIMAR control, PRIMAR is forced to stop sales of Russian (Northern Area) ENCs with immediate effect.Until further notice, new Russian (Northern Area) ENCs and updates will no longer be delivered to PRIMAR."

archive picture issue from weekly updated kmz Primar catalogue file from GeoGarage platform

Primar catalog 04.10.2023

picture issue from weekly updated kmz Primar catalogue file from GeoGarage platform

479 ENC from Head Department of Navigation and Oceanography

Russian Federation Navy (GUNIO) have disappeared in Primar catalogue

Russian Federation Navy (GUNIO) have disappeared in Primar catalogue

UMPORTANT : update (05/10/2023)

Regarding the stopping of sales of Russian (Northern Area) ENCs.

PRIMAR is pleased to inform that the sale and delivery of updates will resume as normal, effective immediately Oct. 5th, 2023..

How China rules the waves

From Financial Times by James Kynge, Chris Campbell, Amy Kazmin and Farhan Bokhari

Pakistan’s Arabian Sea port of Gwadar is perched on the world’s energy jugular. Sea lanes nearby carry most of China’s oil imports; any disruption could choke the world’s second-largest economy.

Owned, financed and built by China, Gwadar occupies a strategic location. Yet Islamabad and Beijing for years denied any military plans for the harbour, insisting it was a purely commercial project to boost trade. Now the mask is slipping.

“As Gwadar becomes more active as a port, Chinese traffic both commercial and naval will grow to this region,” says a senior foreign ministry official in Islamabad. “There are no plans for a permanent Chinese naval base. But the relationship is stretching out to the sea.”

Gwadar is part of a much bigger ambition, driven by President Xi Jinping, for China to become a maritime superpower. An FT investigation reveals how far Beijing has already come in achieving that objective over the past six years.

A Pakistani naval guard at Gwadar port which was financed, built and is now owned by China

© Aamir Qureshi/AFP/Getty Images

Investments into a vast network of harbours across the globe have made Chinese port operators the world leaders. Its shipping companies carry more cargo than those of any other nation — five of the top 10 container ports in the world are in mainland China with another in Hong Kong. Its coastguard has the globe’s largest maritime law enforcement fleet, its navy is the world’s fastest growing among major powers and its fishing armada numbers some 200,000 seagoing vessels.

The emergence of China as a maritime superpower is set to challenge a US command of the seas that has underwritten a crucial element of Pax Americana, the relative period of peace enjoyed in the west since the second world war. As US President-elect Donald Trump prepares to take power, strategic tensions between China and the US are already evident in the South China Sea, where Beijing has pledged to enforce its claim to disputed islands and atolls. Rex Tillerson, the Trump nominee for US secretary of state, said on Wednesday that Washington should block Beijing’s access to the islands. Relations were also dented over Mr Trump’s warm overtures toward Taiwan, which China regards as a breakaway province.

China understands maritime influence in the same way as Alfred Thayer Mahan, the 19th century American strategist. “Control of the sea,” Mr Mahan wrote, “by maritime commerce and naval supremacy, means predominant influence in the world; because, however great the wealth of the land, nothing facilitates the necessary exchanges as does the sea.”

Drummed into military service

The Gwadar template, where Beijing used its commercial know-how and financial muscle to secure ownership over a strategic trading base, only to enlist it later into military service, has been replicated in other key locations.

In Sri Lanka, Greece and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, Chinese investment in civilian ports has been followed by deployments or visits of People’s Liberation Army Navy vessels and in some cases announcements of longer term military contingencies.

The emergence of China as a maritime superpower is set to challenge a US command of the seas that has underwritten a crucial element of Pax Americana, the relative period of peace enjoyed in the west since the second world war. As US President-elect Donald Trump prepares to take power, strategic tensions between China and the US are already evident in the South China Sea, where Beijing has pledged to enforce its claim to disputed islands and atolls. Rex Tillerson, the Trump nominee for US secretary of state, said on Wednesday that Washington should block Beijing’s access to the islands. Relations were also dented over Mr Trump’s warm overtures toward Taiwan, which China regards as a breakaway province.

China understands maritime influence in the same way as Alfred Thayer Mahan, the 19th century American strategist. “Control of the sea,” Mr Mahan wrote, “by maritime commerce and naval supremacy, means predominant influence in the world; because, however great the wealth of the land, nothing facilitates the necessary exchanges as does the sea.”

Drummed into military service

The Gwadar template, where Beijing used its commercial know-how and financial muscle to secure ownership over a strategic trading base, only to enlist it later into military service, has been replicated in other key locations.

In Sri Lanka, Greece and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, Chinese investment in civilian ports has been followed by deployments or visits of People’s Liberation Army Navy vessels and in some cases announcements of longer term military contingencies.

“There is an inherent duality in the facilities that China is establishing in foreign ports, which are ostensibly commercial but quickly upgradeable to carry out essential military missions,” says Abhijit Singh, senior fellow at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi. “They are great for the soft projection of hard power.”

Data compiled or commissioned by the Financial Times from third-party sources show the extent of China’s dominance in most maritime domains.

Data compiled or commissioned by the Financial Times from third-party sources show the extent of China’s dominance in most maritime domains.

Beijing’s shipping lines deliver more containers than those from any other country, according to data from Drewry, the shipping consultancy. The five big Chinese carriers together controlled 18 per cent of all container shipping handled by the world’s top 20 companies in 2015, higher than the next country, Denmark, the home nation of Maersk Line, the world’s biggest container shipping group.

In terms of container ports, China already rules the waves. Nearly two-thirds of the world’s top 50 had some degree of Chinese investment by 2015, up from about one-fifth in 2010, according to FT research.

And those ports handled 67 per cent of global container volumes, up from 42 per cent in 2010, according to Lloyd’s List Intelligence, the maritime and trade data specialists. If only containers directly handled by Chinese port operators are measured, the level of dominance is reduced but still emphatic. Of the top 10 port operators worldwide, Chinese companies handled 39 per cent of all volumes, almost double the second largest nation group, according to data from Drewry.

It is not only the world’s biggest ports that have attracted Chinese investments. Dozens of smaller harbours — including some in key strategic locations such as Djibouti, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Darwin in Australia, Maday Island in Myanmar and proposed ports on the Atlantic Ocean islands of São Tomé and Príncipe and in Walvis Bay in Namibia — have also drawn investments or promises of Chinese port construction.

The total size of these investments is difficult to calculate because of sketchy disclosure. But since 2010, Chinese and Hong Kong companies have completed or announced deals involving at least 40 port projects worth a total of about $45.6bn, according to a study by Sam Beatson and Jim Coke at the Lau China Institute, King’s College London, in co-operation with the Financial Times. A dozen other deals — from Carey Island, Malaysia, to Chongjin in North Korea — have been reported without any financial details.

The total size of these investments is difficult to calculate because of sketchy disclosure. But since 2010, Chinese and Hong Kong companies have completed or announced deals involving at least 40 port projects worth a total of about $45.6bn, according to a study by Sam Beatson and Jim Coke at the Lau China Institute, King’s College London, in co-operation with the Financial Times. A dozen other deals — from Carey Island, Malaysia, to Chongjin in North Korea — have been reported without any financial details.

Rounding out a picture of China’s merchant fleet dominance is the country’s fishing fleet, which is by far the largest in the world, according to a recent paper by Michael McDevitt, a former rear admiral in the US navy and now a senior fellow at CNA Strategic Studies, a US think-tank.

“In the Chinese context, maritime power encompasses more than naval power,” wrote Mr McDevitt. “The maritime power equation includes a large and effective coastguard, a world-class merchant marine and fishing fleet, a globally recognised shipbuilding capacity and an ability to harvest or extract economically important maritime resources, especially fish.”

Journey from land to sea

For thousands of years, Chinese emperors focused on defending the middle kingdom against land-based invasions, usually from the north and west. But in 2015 an official white paper on military strategy decreed a big shift that offers a glimpse of the country’s changing maritime objectives.

“The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests,” the document said. It added that the Chinese navy should protect “the security of sea lanes of communication and overseas interests”.

“In the Chinese context, maritime power encompasses more than naval power,” wrote Mr McDevitt. “The maritime power equation includes a large and effective coastguard, a world-class merchant marine and fishing fleet, a globally recognised shipbuilding capacity and an ability to harvest or extract economically important maritime resources, especially fish.”

Journey from land to sea

For thousands of years, Chinese emperors focused on defending the middle kingdom against land-based invasions, usually from the north and west. But in 2015 an official white paper on military strategy decreed a big shift that offers a glimpse of the country’s changing maritime objectives.

“The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests,” the document said. It added that the Chinese navy should protect “the security of sea lanes of communication and overseas interests”.

Analysts say that China’s naval strategy is aimed primarily at denying US aircraft carrier battle groups access to a string of archipelagos from Russia’s peninsula of Kamchatka to the Malay Peninsula in the south, a natural maritime barrier called the “first island chain” within which China identifies its strategic sphere of influence.

Another focus is the string of artificial islands that Beijing has dredged out of coral reefs and rocks to help reinforce China’s claim to most of the South China Sea, putting it on a collision course with neighbours from Vietnam to the Philippines, as well as the US. The artificial islands have been equipped with landing strips and a US think-tank recently said, after analysis of satellite images, that Beijing appeared to have installed anti-aircraft guns, anti-missile systems and radar facilities on them.

Another focus is the string of artificial islands that Beijing has dredged out of coral reefs and rocks to help reinforce China’s claim to most of the South China Sea, putting it on a collision course with neighbours from Vietnam to the Philippines, as well as the US. The artificial islands have been equipped with landing strips and a US think-tank recently said, after analysis of satellite images, that Beijing appeared to have installed anti-aircraft guns, anti-missile systems and radar facilities on them.

Although Beijing plays down such sweeping strategic objectives, the imperative to step up naval security is regularly emphasised in Chinese circles. A 2015 paper in a semi-official journal under the powerful Chinese Academy of Sciences went one step further, calling for China to “make full use of diplomatic and economic methods to establish at strategic maritime locations points for resupply and military bases so as to protect strategic maritime passages”.

Chinese navy submarine off Qingdao in Shandong Province © Guang Niu/AFP/Getty Images

Reality is unfolding in line with the academics’ recommendations. The political justification often used for port investments is “One Belt One Road”, a grand design advocated by Mr Xi to revive the ancient Silk Road trading routes and boost investment and commerce in more than 60 countries in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe.

Gwadar port, for example, is described as the core element in a $54bn China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. At its inception, Chinese involvement in the port was limited to financing and construction, but in 2015 Islamabad handed over ownership to the state-owned China Overseas Port Holding Company on a lease until 2059.

At the time, China claimed the project was purely commercial. Hong Lei, a spokesman for Beijing’s foreign ministry, described the transfer as a “business practice” aimed at boosting “friendly co-operation between the two countries”. The Pakistan side reinforced this line, with Ahsan Iqbal, Pakistan’s minister for planning, development and reform, telling the Financial Times in November last year that there would be “no Chinese military presence” at the port.

Gwadar port, for example, is described as the core element in a $54bn China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. At its inception, Chinese involvement in the port was limited to financing and construction, but in 2015 Islamabad handed over ownership to the state-owned China Overseas Port Holding Company on a lease until 2059.

At the time, China claimed the project was purely commercial. Hong Lei, a spokesman for Beijing’s foreign ministry, described the transfer as a “business practice” aimed at boosting “friendly co-operation between the two countries”. The Pakistan side reinforced this line, with Ahsan Iqbal, Pakistan’s minister for planning, development and reform, telling the Financial Times in November last year that there would be “no Chinese military presence” at the port.

During the National Day Holiday this year, China's first ultra-deep-sea oil exploration with self-developed equipment is underway.

The first map of the 3,000-meter-deep water bottom structure drawn by self-developed equipment will be released during the exploration.

source & video : CGTN

Beijing calls in a debt

To the west of Gwadar at Djibouti — on the Horn of Africa’s maritime chokepoint — a similar story has unfolded. China’s initial embrace seemed purely commercial, with the state-owned China Merchants Group taking a stake in the Port of Djibouti’s container terminal in 2012 and paving the way for a $9bn investment including the construction of a liquefied natural gas terminal, a wharf for livestock and a trade logistics park.

But in 2016, Beijing acknowledged that its plans for Djibouti had an additional dimension — the construction of the country’s first overseas naval base, ensuring that China’s military will remain in the region until at least 2026 with a contingent of up to 10,000 personnel. Even now, though, Beijing’s official media calls the base a “logistics centre”.

The financial firepower at China’s disposal can make its entreaties irresistible. In Sri Lanka, President Maithripala Sirisena suspended a $1.4bn “port city” project being built by Chinese companies at Colombo shortly after he took power in 2015. Mr Sirisena was wary over China’s growing influence, as dramatised by two unannounced visits from a PLAN submarine and warship to a Colombo container terminal owned by a Chinese state company in late 2014.

To the west of Gwadar at Djibouti — on the Horn of Africa’s maritime chokepoint — a similar story has unfolded. China’s initial embrace seemed purely commercial, with the state-owned China Merchants Group taking a stake in the Port of Djibouti’s container terminal in 2012 and paving the way for a $9bn investment including the construction of a liquefied natural gas terminal, a wharf for livestock and a trade logistics park.

But in 2016, Beijing acknowledged that its plans for Djibouti had an additional dimension — the construction of the country’s first overseas naval base, ensuring that China’s military will remain in the region until at least 2026 with a contingent of up to 10,000 personnel. Even now, though, Beijing’s official media calls the base a “logistics centre”.

The financial firepower at China’s disposal can make its entreaties irresistible. In Sri Lanka, President Maithripala Sirisena suspended a $1.4bn “port city” project being built by Chinese companies at Colombo shortly after he took power in 2015. Mr Sirisena was wary over China’s growing influence, as dramatised by two unannounced visits from a PLAN submarine and warship to a Colombo container terminal owned by a Chinese state company in late 2014.

“That was clear testimony as to how an economic project acquires a military dimension for China,” says Brahma Chellaney, professor of Strategic Studies at New Delhi’s Centre for Policy Research. “The progression is quite rapid.”

Following Mr Sirisena’s intervention, Beijing piled diplomatic pressure on Sri Lanka, using as leverage the huge debts that Colombo had built up with Chinese state banks. Last July, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, arrived with an uncompromising message, according to a Sri Lankan government official who declined to be identified.

“He was reading the riot act,” says the Sri Lankan official. “Unless the government pulled all their fingers out, and got the project back on stream, China would abandon Sri Lanka altogether.”

Sri Lanka, which has debts of around $8bn with Beijing, duly complied. A month later, the government signed an agreement with the China Harbour Engineering Company, paving the way for the resumption of work on the project after a break of nearly 18 months.

In a related deal a Chinese company agreed to pay $1bn for a controlling stake in the new port at Hambantota on the country’s south coast, giving Beijing another modern harbour on the Indian Ocean. Hambantota had been built by a Chinese construction company with Chinese loans.

Other parts of the Indian Ocean also loom large in Beijing’s ambition to rule the seas. Under a bilateral military agreement, Chinese naval vessels use ports in the Seychelles as hubs from which they conduct anti-piracy patrols. In the Maldives, a visit by Mr Xi in 2014 officially inducted the tiny string of atolls with a population of 350,000 people into the One Belt programme, with promises of infrastructure investments.

In Greece too, China’s acquisition of a controlling stake in Piraeus, one of Europe’s largest ports, signalled a merging of commercial and strategic agendas. When Alexis Tsipras, the country’s prime minister, hosted a Chinese warship and naval top brass in Piraeus in early 2015, Chinese state media quoted him as saying he supported its sale to Chinese interests. Less than a year later, it was sold for $420m.

Chinese officials relished the moment. They recalled how Beijing was embarrassed in 2011 when it needed to evacuate 36,000 Chinese workers from Libya as violence broke out, forcing it at short notice to enlist the help of Greek merchant ships to make the first few rescue missions.

“If that was to happen again,” says a Chinese official who declines to be identified. “We would be much better prepared. We could use the Chinese navy and take the evacuees to our own port at Piraeus.”

Following Mr Sirisena’s intervention, Beijing piled diplomatic pressure on Sri Lanka, using as leverage the huge debts that Colombo had built up with Chinese state banks. Last July, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, arrived with an uncompromising message, according to a Sri Lankan government official who declined to be identified.

“He was reading the riot act,” says the Sri Lankan official. “Unless the government pulled all their fingers out, and got the project back on stream, China would abandon Sri Lanka altogether.”

Sri Lanka, which has debts of around $8bn with Beijing, duly complied. A month later, the government signed an agreement with the China Harbour Engineering Company, paving the way for the resumption of work on the project after a break of nearly 18 months.

In a related deal a Chinese company agreed to pay $1bn for a controlling stake in the new port at Hambantota on the country’s south coast, giving Beijing another modern harbour on the Indian Ocean. Hambantota had been built by a Chinese construction company with Chinese loans.

Other parts of the Indian Ocean also loom large in Beijing’s ambition to rule the seas. Under a bilateral military agreement, Chinese naval vessels use ports in the Seychelles as hubs from which they conduct anti-piracy patrols. In the Maldives, a visit by Mr Xi in 2014 officially inducted the tiny string of atolls with a population of 350,000 people into the One Belt programme, with promises of infrastructure investments.

In Greece too, China’s acquisition of a controlling stake in Piraeus, one of Europe’s largest ports, signalled a merging of commercial and strategic agendas. When Alexis Tsipras, the country’s prime minister, hosted a Chinese warship and naval top brass in Piraeus in early 2015, Chinese state media quoted him as saying he supported its sale to Chinese interests. Less than a year later, it was sold for $420m.

Chinese officials relished the moment. They recalled how Beijing was embarrassed in 2011 when it needed to evacuate 36,000 Chinese workers from Libya as violence broke out, forcing it at short notice to enlist the help of Greek merchant ships to make the first few rescue missions.

“If that was to happen again,” says a Chinese official who declines to be identified. “We would be much better prepared. We could use the Chinese navy and take the evacuees to our own port at Piraeus.”

Links :

- Courrier International : Comment la Chine étend son empire maritime

- WSJ : China Is Gaining Long-Coveted Role in Arctic, as Russia Yields

- Maritime Executive : China is Leading the World in Naval Sensing and Navigation R&D

- Reuters : In U.S.-China AI contest, the race is on to deploy killer robots

Tuesday, October 3, 2023

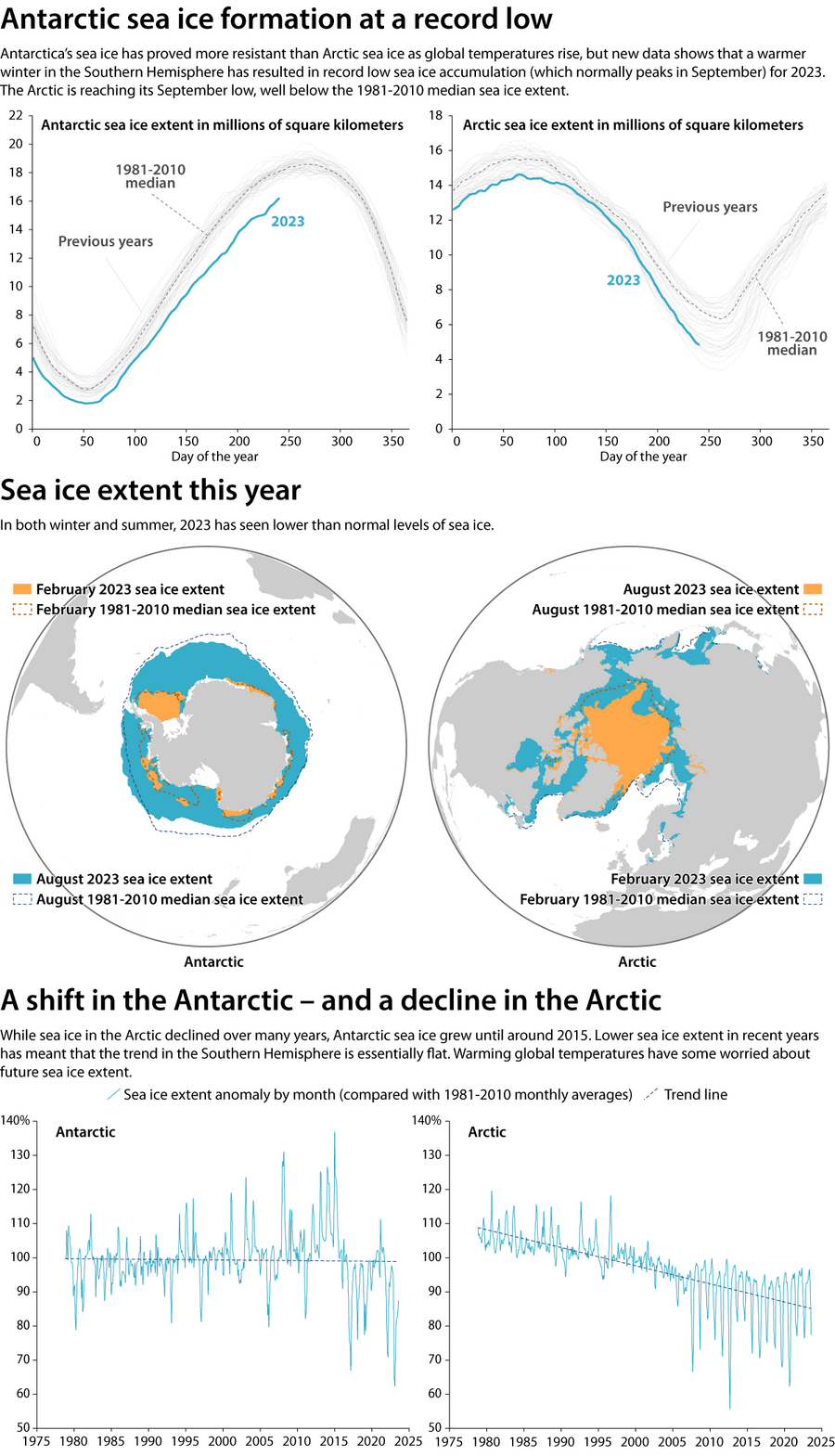

Sea ice is shrinking. These maps show by how much

A team of international scientits heads to Chile's station Bernardo O'Higgins, Antarctica, Jan 22, 2015

photo : Natacha Pisarenko / AP / File

From CS Monitor by Jacob Turcotte

It can be hard to visualize the magnitude of change underway on a warming planet.

What does a hundred gigatons of ice look like?

How many millions of Olympic swimming pools can you imagine?

Our charts with this article aim to contextualize the massive changes underway in the Antarctic, with data from the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The headline: A warm southern winter has produced far less sea ice than normal, indicating a fundamental change may have taken place in this historically variable climate.

By the end of August, Antarctic sea ice extent (the total region with at least 15% sea ice cover) was about 860,000 square miles smaller than the average August extent from 1981 to 2010. That’s a patch of ocean the size of Saudi Arabia, normally filled with ice but now open ocean, the lowest winter level since recording began 45 years ago.

Our charts with this article aim to contextualize the massive changes underway in the Antarctic, with data from the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The headline: A warm southern winter has produced far less sea ice than normal, indicating a fundamental change may have taken place in this historically variable climate.

By the end of August, Antarctic sea ice extent (the total region with at least 15% sea ice cover) was about 860,000 square miles smaller than the average August extent from 1981 to 2010. That’s a patch of ocean the size of Saudi Arabia, normally filled with ice but now open ocean, the lowest winter level since recording began 45 years ago.

National Snow and Ice Data Center |Jacob Turcotte/Staff

And the overall trend of sea ice growth in Antarctica has reversed in the past few years, from growth to a slight decline.

Loss of sea ice in the Northern Hemisphere is also occurring and has long been emblematic of the climate crisis. Antarctic sea ice has appeared more resilient.

As sea ice steadily declined in the Arctic, Antarctic sea ice has oscillated between record highs and lows over previous decades.

But in 2016, sea ice in Antarctica began a steady downward trend.

Sea ice melt won’t directly raise sea levels – the ice is already floating in the ocean.

Sea ice melt won’t directly raise sea levels – the ice is already floating in the ocean.

But the loss of sea ice means less sunlight is reflected into space, accelerating warming seas and potentially threatening ice shelves that hold back the continent’s massive glaciers, some of which are melting perilously quickly.

Scientists warn that if Antarctica’s Thwaites glacier collapses, global sea levels could rise up to 2 feet – a change that could then endanger other glaciers too.

The stakes are significant for polar ecosystems, not just global sea levels and ocean currents.

The stakes are significant for polar ecosystems, not just global sea levels and ocean currents.

One recently released study found a dramatic decline in survival rates of young emperor penguins, an iconic bird as the largest of penguin species.

If ice melts or breaks up too early, penguin chicks can die because they haven’t developed their adult waterproof feathers.

Scientists have also been tracking some unusual breaking of ice shelves, which are formed by glaciers and are much thicker than the thin and variable sea ice.

“It’s still an unknown place,” Catherine Walker of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution told the Monitor, after the surprise collapse of the Conger ice shelf last year.

Links :

Scientists have also been tracking some unusual breaking of ice shelves, which are formed by glaciers and are much thicker than the thin and variable sea ice.

“It’s still an unknown place,” Catherine Walker of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution told the Monitor, after the surprise collapse of the Conger ice shelf last year.

Links :

- NASA : Melting on Humboldt Glacier

Monday, October 2, 2023

‘Dark’ ships are faking their locations to move oil around the world — and it’s likely worth billions of dollars

A

Russian-chartered oil tanker in the sea off Morocco.

Maritime

technology company Windward identified the area as a hub for smuggling

oil.

Europa Press | Getty Images

Europa Press | Getty Images

From CNBC by Lucy Chandley

The number of vessels hiding their locations by switching off or manipulating their automatic identification systems (AIS) has increased, according to maritime technology firm Windward.

Experts suspect these ships are tankers involved in illicit activity to cover up the origin of the oil they carry, evading western nations’ sanctions against Russia and Venezuela.

This under-the-radar oil trade is likely to be worth billions of dollars.

Ships are faking their locations to engage in illicit activity — and rising numbers appear to be doing so to trade goods that are likely to be worth billions of dollars.

So-called “dark vessels” shipping Russian oil in a suspected evasion of the G7′s $60 a barrel price cap, tankers going under-the-radar in Venezuelan waters, and cargo ships allegedly smuggling grain from Ukraine are being uncovered by satellite technology that can identify when vessels report a false location.

Large ships have to be fitted with automatic identification systems (AIS) and must broadcast their locations to prevent collisions, per International Maritime Organization requirements.

But some are switching off their location transponders, or engaging in AIS “spoofing,” where a vessel reports that it is in one location but is actually in another — possibly hundreds of miles away.

Data from maritime technology company Windward showed a rise of 12% in location manipulation among oil tankers and ships carrying dry cargo such as grain for the first half of 2023 when compared to the same period last year, and an 82% increase on the first half of 2021.

Developments in technology are making it easier to track this kind of tampering, while new efforts to make ships’ locations public is shining a light on such activities, according to John Lusk, CEO of Spire Maritime, an analytics company that provides data to governments and private companies.

DOJ criminal cases and civil forfeiture actions involving shipping companies carrying illicit Iranian oil shows how the U.S. Government might react to AIS spoofing.

Christopher Swift PARTNER, FOLEY & LARDNER

“We’re starting to see even more focus and visibility on the maritime industry because of the sanctions,” Lusk told CNBC by video call, referring to the G7′s sanctions against Russia, with the EU’s latest measures barring those vessels that have turned off or spoofed their AIS from entering ports.

“Because of dark vessels, a lot of the illegal shipping is starting to increase,” he said.

When contacted by CNBC to ask how many such vessels have been turned away from European ports following the latest sanctions, an EU spokesperson said such information “is not for public disclosure.” “Member States inform each other and the Commission about refusals of a port access call,” the spokesperson said via email.

“When you have black markets where they’re blatantly breaking the law, whether that’s breaking constraints, whether it’s doing things that are going into EEZs [exclusive economic zones] in fishing, whether it’s shipping products under the radar, there’s just a lot of things now that are more visible, and a lot more recognition in terms of how that’s impacting the global economy,” Lusk said.

Cargo cover up

The G7 capped Russian oil sales at $60 a barrel to constrain revenues the Kremlin can make from the commodity, but according to Ami Daniel, co-founder and CEO of Windward, the illicit movement of Russian oil could be worth tens of billions of dollars.

Over the past year, Windward’s technology identified more than 1,100 tankers associated with Russia that went dark by switching off or manipulating their AIS, a Windward spokesperson told CNBC by email.

“It’s millions of barrels of oil,” Daniel told CNBC by video call.

For example, “500 vessels could be [carrying] 800 million barrels. Then multiply that by the price of oil — let’s call it $60. Sounds to me like 48 billion bucks,” he said.

In an online article, Windward said its data showed the number of dark ship-to-ship oil tanker transfers had increased in the Alboran Sea north of Morocco since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which it said suggested a smuggling operation.

Such transfers allow one vessel to take oil from another without investigating the oil’s purchase price, and can also mask the commodity’s origin.

The G7 capped Russian oil sales at $60 a barrel to constrain revenues the Kremlin can make from the commodity, but according to Ami Daniel, co-founder and CEO of Windward, the illicit movement of Russian oil could be worth tens of billions of dollars.

Over the past year, Windward’s technology identified more than 1,100 tankers associated with Russia that went dark by switching off or manipulating their AIS, a Windward spokesperson told CNBC by email.

“It’s millions of barrels of oil,” Daniel told CNBC by video call.

For example, “500 vessels could be [carrying] 800 million barrels. Then multiply that by the price of oil — let’s call it $60. Sounds to me like 48 billion bucks,” he said.

In an online article, Windward said its data showed the number of dark ship-to-ship oil tanker transfers had increased in the Alboran Sea north of Morocco since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which it said suggested a smuggling operation.

Such transfers allow one vessel to take oil from another without investigating the oil’s purchase price, and can also mask the commodity’s origin.

Cargo ships and car ferries cross the Kerch Strait, an area of “dark activity,” according to marine technology company Windward.

Anadolu Agency | Getty Images

Anadolu Agency | Getty Images

Windward also identified a “Russian grain drain” that appeared to show a cargo ship carrying grain “engaging in a dark activity” in the Kerch Strait — the body of water connecting the Azov Sea that has Russian and Ukrainian boundaries — to the Black Sea.

Two cargo vessels left Kerch to deliver grain to Morocco and the Arabian Gulf, Windward said.

Spire, meanwhile, identified and tracked 50 very large crude carriers that it said covered up their whereabouts to ship oil from Venezuela.

The U.S. has sanctions against Venezuela, but Spire estimated that 108 million barrels of oil — worth around $8 billion in mid-July, when the company published its tracking data — were moved from the South American country to East Asia between Nov. 1 last year and June 29.

Tankers manipulating the location they transmitted most commonly appeared to be in waters around the oil fields of Angola — but Spire’s data showed their true positions to be across the South Atlantic Ocean in Venezuela’s EEZ.

Vessels then reported an accurate location once they sailed close to South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, with China and Malaysia their most likely destinations, the company added.

Data also showed the draft of the vessels changed, suggesting cargo had been unloaded, Spire said.

AIS manipulation

As technology has developed, it has become relatively easy to tell whether a ship has turned off its AIS, according to Iain Goodridge, Spire’s senior director of radio frequency geolocation products.

“Let’s say you’re a good-sized oil tanker, and you turn off your AIS.

You’re going to hear about it not only from probably your ship owners, your shipbrokers, you’re going to hear about it from the insurance company … they’re going to know that it was off.

So that’s definitely moved that focus into, okay, I’m now going to manipulate that signal,” he told CNBC by video call.

This can be done in a number of ways, a Spire spokesperson told CNBC by email.

These include switching off the AIS transponder for a period of time; by adding a device between the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) data and the transponder to suggest the vessel is on one route when it’s actually sailing in a different direction; or via a software hack that has the transponder report a latitude and longitude that does not change despite the vessel moving.

The spoofing technology is “almost plug and play,” Goodridge said, “It’s similar to, you know, you can go online and buy GPS jammers for your car … it is that accessible,” he added.

As technology has developed, it has become relatively easy to tell whether a ship has turned off its AIS, according to Iain Goodridge, Spire’s senior director of radio frequency geolocation products.

“Let’s say you’re a good-sized oil tanker, and you turn off your AIS.

You’re going to hear about it not only from probably your ship owners, your shipbrokers, you’re going to hear about it from the insurance company … they’re going to know that it was off.

So that’s definitely moved that focus into, okay, I’m now going to manipulate that signal,” he told CNBC by video call.

This can be done in a number of ways, a Spire spokesperson told CNBC by email.

These include switching off the AIS transponder for a period of time; by adding a device between the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) data and the transponder to suggest the vessel is on one route when it’s actually sailing in a different direction; or via a software hack that has the transponder report a latitude and longitude that does not change despite the vessel moving.

The spoofing technology is “almost plug and play,” Goodridge said, “It’s similar to, you know, you can go online and buy GPS jammers for your car … it is that accessible,” he added.

Insurance implications

OFAC, the U.S. Treasury Department body that administers and enforces sanctions, issued an alert in April about a “possible evasion of the Russian oil price cap,” warning U.S.

companies such as marine insurers that vessels they cover could be using “deceptive practices” like AIS spoofing to hide their presence at Russian ports such as Kozmino.

OFAC recommended firms use maritime intelligence providers “to improve detection of AIS manipulation.”

Christopher Swift, a partner and member of U.S. law firm Foley & Lardner’s government enforcement defense and investigations practice, called AIS spoofing “highly suspect.”

“If you’re in the insurance industry, and you’re not paying attention to this, you really need to start paying attention,” Swift told CNBC by video call.

OFAC, the U.S. Treasury Department body that administers and enforces sanctions, issued an alert in April about a “possible evasion of the Russian oil price cap,” warning U.S.

companies such as marine insurers that vessels they cover could be using “deceptive practices” like AIS spoofing to hide their presence at Russian ports such as Kozmino.

OFAC recommended firms use maritime intelligence providers “to improve detection of AIS manipulation.”

Christopher Swift, a partner and member of U.S. law firm Foley & Lardner’s government enforcement defense and investigations practice, called AIS spoofing “highly suspect.”

“If you’re in the insurance industry, and you’re not paying attention to this, you really need to start paying attention,” Swift told CNBC by video call.

U.S.action

In May, the Treasury Department said the oil price cap had achieved both of its aims: to maintain the supply of Russian oil but restrict its revenues.

Swift expects the U.S. government to investigate further, although he added that enforcement “tends to lag behind the newest sanctions [and] circumvention strategies,” he told CNBC by email.

On Friday Sept. 8, the U.S. Justice Department said it had seized nearly a million barrels of Iranian crude oil that violated sanctions, sentencing vessel owner Suez Rajan Limited to three years’ corporate probation and fining the company almost $2.5 million.

“Participants in the scheme attempted to disguise the origin of the oil using ship-to-ship transfers, false automatic identification system reporting, falsified documents and other means,” the DOJ said in an online release.

This might pave the way for Russian sanctions evasions to be punished, Swift said.

“Recent DOJ criminal cases and civil forfeiture actions involving shipping companies carrying illicit Iranian oil shows how the U.S.

Government might react to AIS spoofing and Russian oil smuggling in the future,” Swift told CNBC.

Links:

- GeoGarage blog : 'Dark ships' emerge from the shadows of the Nord Stream ... / 'Going Dark' is so 2019 / Spoofed AIS signals form symbol of Russian invasion / Global analysis shows where fishing vessels turn off their ... /A radar-illuminated ocean reveals dark fleets / Iceye releases dark vessel detection product / Russian-owned super yachts going dark to avoid sanction ... / AIS data : the danger in the hands of novices / A mysterious fleet is helping Russia ship oil around the ... / Russian tanker falsifies AIS data, hides likely activity ... / Ghost ships, crop circles, and soft gold: A GPS mystery in ... / Shadow tanker fleet: A ticking time bomb waiting to cause ... / London ship insurers accused of enabling fishing vessels .../ A boat went dark. Finding it could help save the world's fish /

Sunday, October 1, 2023

Tànana in Antarctica

January 2023, 7 women and 4 men get on board a sailboat, heading to the end of the world, with the purpose of exploring the discovery of the Antarctic Peninsula commonly called the white continent and to awaken interest in the protection of the planet and the vulnerability of the south pole.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)