Saturday, February 11, 2023

How does math guide our ships at sea? - George Christoph

Friday, February 10, 2023

The fourth battle of the Atlantic is underway

Credit: Flt. SGT ARTIGUES/FRAF/NATO

This new struggle is being waged beneath the waves.

But just as in earlier Atlantic campaigns, it is a conflict the US and its allies cannot afford to lose.

A battle for the undersea domain between North America and the European continent was already underway in 2016, my colleague, Dr. Alarik Fritz and I warned that year.

Any doubts about this were surely removed by September’s unattributed attack on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in the Baltic Sea by some nefarious adversary.

This was no accident — rather it was deliberate sabotage — as stated by Swedish investigators and the European Union (EU.)

“This is not a kinetic fight,” we wrote in 2016.

“It is a struggle between Russian forces that probe for weakness, and US and NATO anti-submarine warfare (ASW) forces that protect and deter. Just like in the Cold War, the stakes are high.”

If anything, the stakes have now increased.

There are numerous threats below the sea’s surface, including the more obvious, like Russia’s advanced submarines, which while not as good as the US Virginia or the UK’s Astute class, are still very good indeed.

What has really changed is the understanding of just how reliant Western society is on undersea cable networks for the essentials of everyday life.

Where once were telephone lines, the seabed is now crisscrossed by data cables on which the modern world depends — our military and financial systems are heavily reliant on them.

More than 95% of communications channels are subsea.

A 2017 report written by Rishi Sunak, then a backbench MP and now Britain’s prime minister, and endorsed by Admiral James Stavridis, US Navy (Ret), former NATO Supreme Allied Commander, made the point.

“Funneled through exposed choke points (often with minimal protection) and their isolated deep-sea locations entirely public, the arteries upon which the internet and our modern world depends have been left highly vulnerable,” the report said.

How did we get here?

The German Navy perfected the U-boat, a diesel-powered vessel that charged its batteries on the surface so it could subsequently dive on battery power and wreak havoc on allied convoys crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

The Germans made the strategic decision to conduct unrestricted submarine warfare on merchant vessels and when the U-21 sunk the Lusitania, a British-flagged cruise ship with many Americans onboard, the act helped bring the United States into the war.

This turned the tide on the ground, and Imperial Germany suffered a humiliating defeat, resulting in the lopsided Treaty of Versailles.

The subsequent rise of Nazism caused a return to conflict with allied powers in World War II.

The United States and its allies soon felt the wrath of a seasoned and much improved German submarine force in the Second Battle of the Atlantic.

Led by Fleet Admiral Karl Dönitz, himself a submarine hero from the First World War, the Germans wrought havoc on convoys providing vital war material.

After Pearl Harbor, the United States once again threw the full weight of its industrial might and technological know-how into the fight.

1942 and 1943 were pivotal years in the Second Battle of the Atlantic.

The classic movie Das Boot, released in 1981, chronicles the ultimate demise of a force that was outnumbered and overmatched in technology.

German submarine losses were staggering — of the 40,000 submariners who went to sea during the war, almost 30,000 perished.

Following the defeat of Nazi German and Imperial Japan, it was not long before the United States and her allies entered a bipolar contest with the Soviet Union resulting in the Cold War.

This Third Battle of the Atlantic resulted in a nuclear and naval armaments race between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Ours was a cost-imposing strategy, which neither the industrial base nor the Communist Party could keep up with, ultimately contributing to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Despite hopes for a peace dividend, there was little pause.

Following a chaotic few years, former KGB agent, Vladimir Putin, emerged as the heir apparent in Moscow.

Putin’s provocative and combative speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 set the tone for the shape of things to come.

In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia and a new era of fiercer competition began, reaching its peak in February 2022 with the all-out invasion of Ukraine.

Despite Russian failures ashore and at sea — including the embarrassing loss of Russia’s Black Sea flagship Moskva, one covert program remains viable and lethal.

That is the Russian submarine force.

Russia has continued to pour rubles into the Russian design bureau and the submarine force because they see it as an asymmetric strategy that can challenge the West.

In terms of technology and quieting, the United States submarine force is number one in the world, with Russia, not China, as the pacing threat.

Russia has consistently produced high-quality nuclear-powered submarines that are revolutionary in their own right, from the November-class to Victor I, II, and III-class, to the deep diving titanium hulled Alfa-class, to the Mike, Sierra, and Akula-classes, and now to the present-day Severodvinsk and Belgorod-class boats.

Suffice it to say that Severodvinsk is a very capable adversary equipped with state-of-the-art cruise missiles and torpedoes, but it cannot outmatch the US Virginia-class boats, and we must keep it that way.

Belgorod is a new class of submarine with a curious dual-mission capability.

It carries the Poseidon-class torpedo, which Putin himself revealed a couple of years ago, boasting a 65-foot length with self-contained nuclear propulsion that could carry the weapon at high speed across the Atlantic Ocean and a dual-use, conventional or nuclear warhead.

Furthermore, the submarine is equipped with a deep-diving mini-sub that could threaten Western undersea critical infrastructure.

Working together with allies, we can mitigate the threat.

It is both fortunate and timely that NATO established a new Joint Forces Command on this side of the Atlantic.

JFC Norfolk and the associated US Second Fleet Headquarters have as their charter the safety and security of the Trans-Atlantic Bridge.

The Atlantic is not the only contested waterway.

Russia’s presence in the Arctic, Baltic, Mediterranean, and Black Seas is also problematic.

By creating and adhering to a robust maritime strategy, NATO can overcome these challenges.

Investments in undersea warfare, i.e., submarines, remotely piloted or autonomous systems, undersea surveillance, and a network that supports a common operating picture can help make contested waters more transparent and the targeting problem easier.

Having Sweden and Finland join NATO will transform the Baltic Sea into a NATO lake.

The same cannot be said for the Black Sea, which is lacking a NATO maritime presence right now, an issue that must be rectified soon.

The same could be said for the Arctic, which is rapidly becoming more blue than white with climate change, leading to an increased presence of maritime traffic.

There is still much work to be done to win the Fourth Battle; let’s get on with it.

- US Naval Institute : The Fourth Battle of the Atlantic

- DailyMail : America is fighting the Fourth Battle of the Atlantic: Navy admiral warns Russian submarines are waging Cold War-style operations in 'alarming and confrontational ways'

- Seymour Hersh : How America Took Out The Nord Stream Pipeline

- The Times : US bombed Nord Stream gas pipelines, claims investigative journalist Seymour Hersh

- Insider : The CIA warned Germany weeks ago about a possible attack on the Nord Stream natural-gas pipelines, report says

- Bloomberg : Russia Blames US for Nord Stream Blasts, Threatens Consequences

- Reuters : White House says blog post on Nord Stream explosion 'utterly false' / Putin ally compares Nord Stream sabotage to CIA-backed attacks of 1980s

- Democracy Now : White House Denies Seymour Hersh Report That U.S. Sabotaged Nord Stream Pipelines

- GeoGarage blog : 'Dark ships' emerge from the shadows of the Nord Stream ... / A deep dive into risks for undersea cables, pipes / 'Dark ships' emerge from the shadows of the Nord Stream ... / A deep dive into risks for undersea cables, pipes / The most vulnerable place on the Internet

Thursday, February 9, 2023

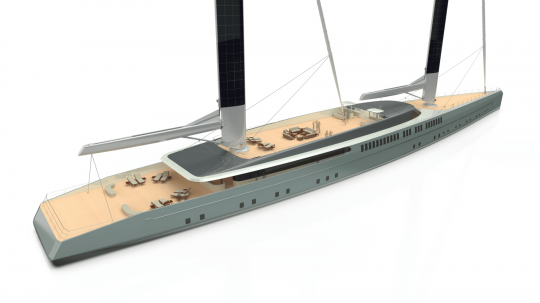

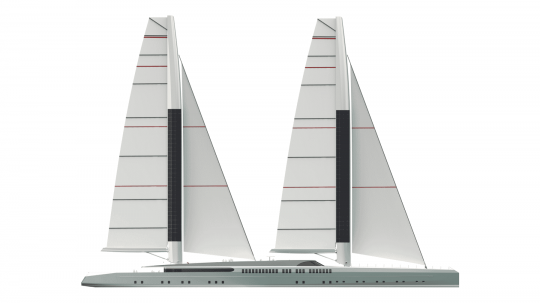

Wing 100, a sailing superyacht that plays the sustainable navigation card

Presented as easy to sail, it also promises significant energy savings.

From BoatNews by Chloé Torterat

A real super yacht with sails

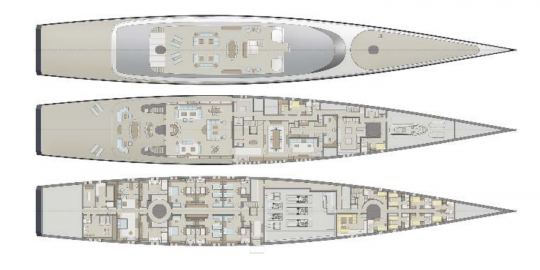

Wing 100 is a new concept in sailing superyachts from Royal Huisman, in collaboration with Dykstra Naval Architects and Mark Whiteley Design.

This 330-foot, 100-meter-long schooner is not a sail-assisted motor yacht, but a sailing yacht in its own right.

If it is built, it will be one of the 10 largest sailing ships in the world, but above all the largest yacht built by the Dutch shipyard.

The idea is to offer a real sailing superyacht to long-distance cruising enthusiasts, but also to offer an alternative to motoryacht owners with a more sustainable navigation, while keeping the same level of comfort.

A minimalist design

Entirely built in aluminum, the Wing 100 has a vertical bow, a fairly long waterline and a self-supporting carbon rig, without shrouds or spreaders, or standing rigging, with an air draft of 73 m.

To facilitate the implementation of the sail plan, and thus maximize sailing under sail, the shipyard has opted for autonomous rotating wing masts, remotely controlled and equipped with furling carbon booms.

The mainsails can thus be hoisted in a few minutes, and reefed in the same way in case of a gale.

The estimated speed under sail of Wing 100 could exceed 24 knots.

Equipment to navigate in a more sustainable way

In addition, 480 m2 of solar panels are integrated into the carbon mats to generate 250 kW/day, equivalent to a fuel saving of more than 20,000 liters/year.

A hydro-generator produces up to 200 kW under sail to power the onboard systems and recharge the large battery bank.

This replaces the use of a generator and ensures silence at anchor or under sail.

Eventually, the generator could be replaced by a fuel cell.

In total, all the systems of the Wing 100 have been designed to save about 225,000 liters of fuel per year, compared to motor superyachts of the same size.

On the Wing 100, the layout is designed for 12 guests, a nanny and 16 crew members.

The living area is spread over three decks, from the flybridge to the lower deck, all connected by an elevator and stairs.

Here you can enjoy outdoor dining and relaxation.

Stairs just forward of the double helm station give access to the bridge deck, a half-deck between the main decks and the flybridge for good operational visibility.

The main deck offers plenty of volume thanks to the long waterline and generous beam.

The interior is sober, with custom spaces for each owner to arrange as they wish.

There could be an owner's suite, a VIP suite, five guest cabins and a nanny cabin.

Crew quarters are located forward.

The main deck features a 16-person dining room, a bar, an indoor/outdoor lounge and additional outdoor dining areas.

The spacious main deck area has stairs leading to a large swim platform.

This layout is only an example, as each owner can choose the layout that suits him or her.

- Royal Huisman : Wing 100 unveiled

- SuperYacht Times : Wing 100: The sustainable and energy efficient 100m sailing yacht concept from Royal Huisman

- YachtDesign : Wing 100: Royal Huisman presents the concept for a 100-metre sailing yacht

Wednesday, February 8, 2023

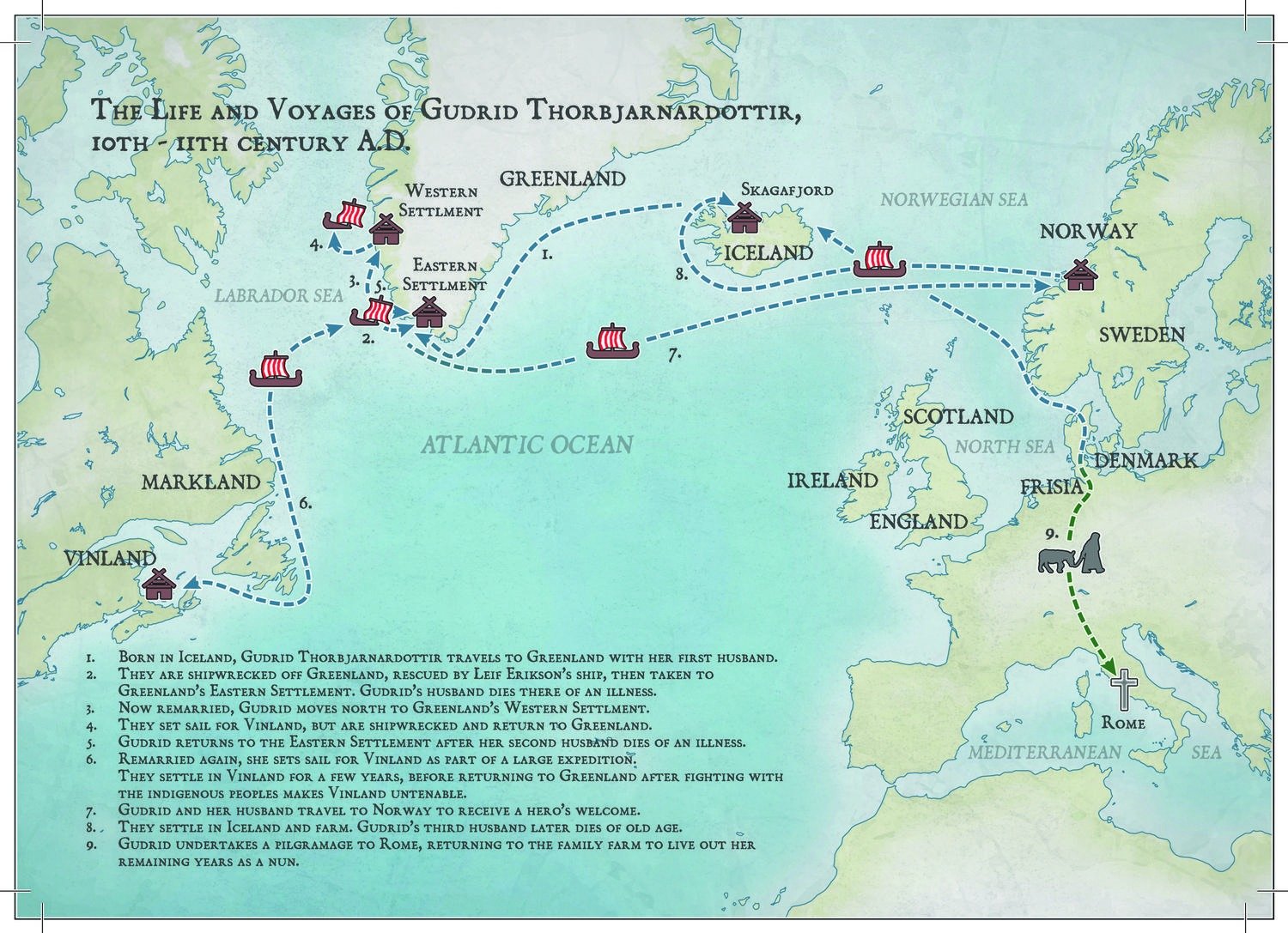

The Viking woman who sailed to America and walked to Rome

- Move over Erik the Red and Leif Erikson, and make room for Gudrid the Far-Traveled.

- She was the first European woman to give birth in America, as well as the first nun in Iceland.

- She roamed Vinland (in modern Canada) and visited Rome.

No medieval woman traveled further than her.

And she concluded her global odyssey with a pilgrimage on foot to Rome.

Yet few today can name this extraordinary Viking lady, even if they have heard of Erik the Red and Leif Erikson, her father- and brother-in-law.

Her full name, in modern Icelandic, is Guðríður víðförla Þorbjarnardóttir — Gudrid the Far-Traveled, daughter of Thorbjorn.

She was born around 985 AD on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in western Iceland and died around 1050 AD at Glaumbær in northern Iceland.

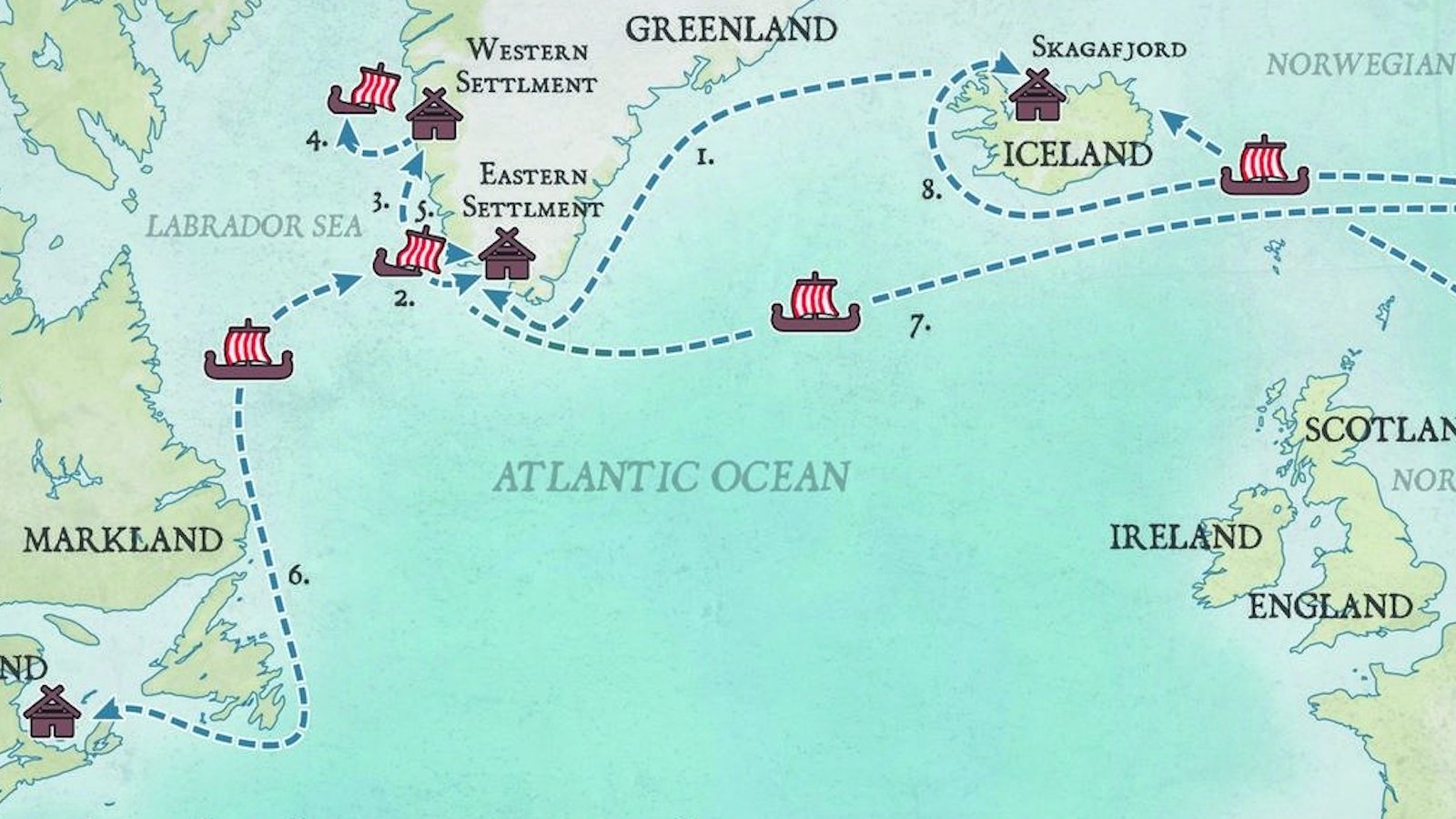

This map shows the extraordinary extent of her travels in between those dates and places.

In all, she made eight Atlantic sea voyages, at a time when those were very dangerous and often deadly.

One of three such statues, this one is at Glaumbær in northern Iceland.

(Credit: diego_cue via Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 3.0)

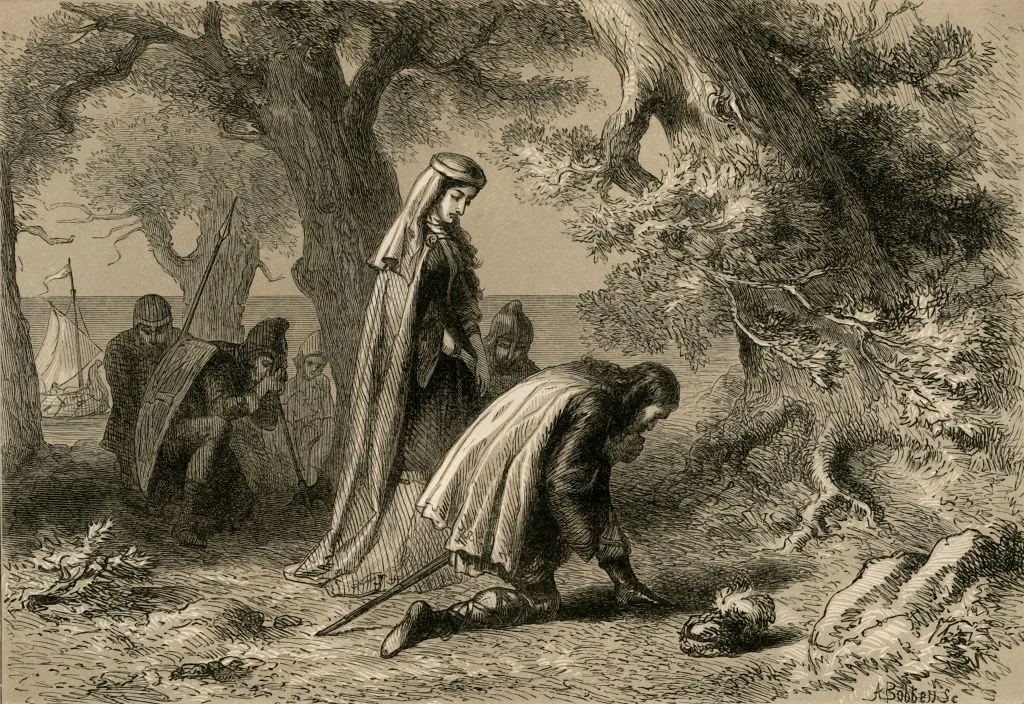

What little we know of her comes from the Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders.

These are collectively known as the Vinland Sagas, as they describe the Viking exploration and attempted settlement of North America — part of which the explorers called “Vinland,” after the wild grapes that grew there.

These sagas were told and retold from memory until they were committed to paper in the 13th century.

Due to those 200 years of oral transmission, they likely contain numerous inconsistencies; Gudrid was married twice according to one saga, three times in the other, for example.

Also, they freely mix fact with fiction.

Their pages crawl with dragons, trolls, and other things supernatural.

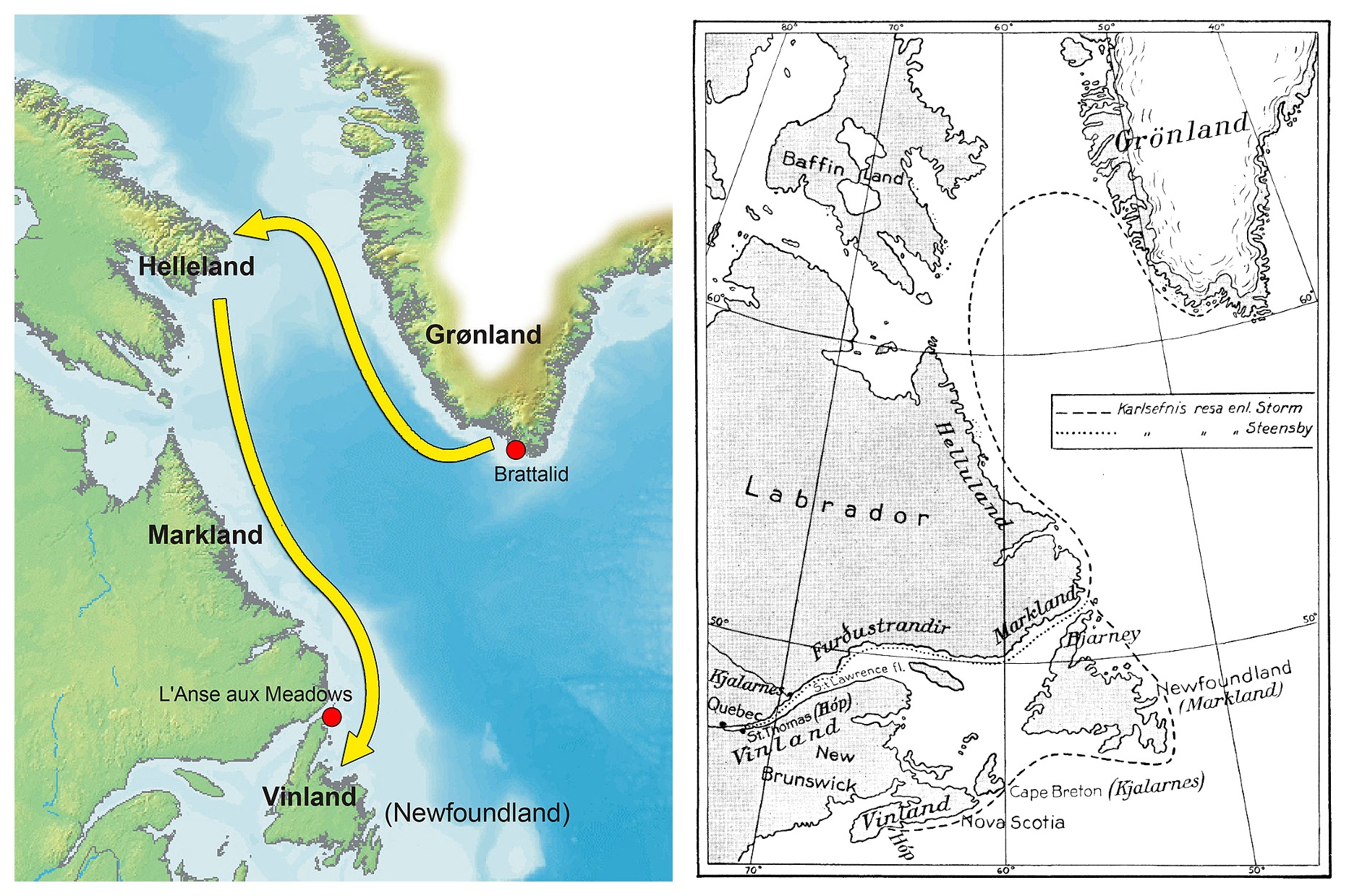

But the central tenet of the sagas has been proven by archaeology: In the 1960s, the remains of a Viking outpost were dug up at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Among the rubble was found a spindle, used for spinning yarn, which was typical women’s work and thus possibly handled by Gudrid herself.

Her character is so central to the Saga of Erik the Red that some have suggested it should rather be called Gudrid’s Saga.

And in the Saga of the Greenlanders, Gudrid is called “a woman of striking appearance and wise as well, who knew how to behave among strangers.”

(Credit: Richard Thomson / Richard Thomson Imagery)

Gudrid’s remarkable story starts when she is around 15, when she travels to Greenland with her father.

According to one of the sagas, she is with her first husband Thorir, who died there the following winter (#1 on the map).

The emigrants suffer terribly on the way to Greenland, with half dying en route and the remainder shipwrecked on a small island off the mainland (#2).

They are rescued by Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red — a friend of her father’s, as it happens.

It is from this event that Leif gets the nickname “Leif the Lucky.” (To this day, Icelanders believe that sea rescues bring the rescuers good luck.)

Gudrid then settles in Greenland (#3) and eventually marries Thorstein Erikson, brother of Leif and son of Erik.

Leif has just returned from a strange new land he discovered across the ocean, and according to one saga, Gudrid joins Thorstein on an unsuccessful trip over to the other side (#4).

Back in Greenland, the newlyweds spend a winter with Thorstein the Black and his wife Grimhild, whose settlement is decimated by a plague.

Gudrid’s husband is among those carried off by the disease, but his corpse rises from its deathbed to foretell her future: She will marry an Icelander, with whom she will have many children and a long life; she will leave Greenland, visit Norway, make a pilgrimage south, and return to Iceland.

Gudrid returns to Greenland’s Eastern Settlement (#5) and marries Thorfinn Karlsefni, a merchant from Iceland.

At her urging, the two lead an attempt to settle Vinland with a party of 60 men, five women, and some livestock (#6).

In Vinland, Gudrid gives birth to Snorri Thorfinnsson, the first reported birth of a European in the New World.

The year is uncertain, however: anywhere between 1005 and 1013 AD.

The attempt at settlement in America lasts just three years.

Harsh conditions, isolation, and hostile relations with the Natives cause the Vikings to pull back.

When Snorri is three, the family leaves Vinland for Europe.

They receive a hero’s welcome at the royal court in Norway (#7), get rich from selling their exotic goods, and settle in Iceland at Glaumbær farm in Skagafjord (#8).

The family leads a peaceful, prosperous life.

Thorfinn dies of old age.

When Snorri marries, Gudrid goes on a pilgrimage to Rome (#9), apparently by herself and mainly on foot.

When Gudrid returns from her last great voyage to Rome, she finds Snorri has built a church for her, as she requested.

Here, she lives out the remainder of her life in solitude and contemplation: the first nun in Iceland, a final achievement in a unique life.

It is not known when exactly Gudrid died, but she did not die in obscurity.

She established a powerful and influential family.

Among her illustrious progeny were three early bishops of Iceland and a 14th-century compiler of Icelandic sagas, including the Saga of Erik the Red, which mentions his famous ancestor.

Gudrid’s own ancestors were Gaelic servants of Unn the Wise, a former Viking queen of Dublin who fled to Iceland around 900 AD and settled her followers in an empty valley, Gudrid’s grandfather among them.

It is possible this female pioneer was an example for Gudrid’s own attempt at group emigration.

Two anecdotes from the sagas shed some light on the fluid multiculturalism in the North Atlantic around the year 1000.

At that time, Christianity was starting to make inroads into Viking communities, which however remained largely pagan.

It seems Gudrid herself was an early Christian convert, but not an inflexible one.

At the home of a family friend, Gudrid is the only woman present who knows a “weird song” that will help the prophetess Thorbjorg perform a magic ritual.

At first, Gudrid refuses to sing it, as she is a Christian woman.

But she is easily convinced that it will help everybody present and not harm her status as a Christian.

Two theories about Viking exploration in North America.

On the left: Helluland is Baffin Island, Markland is Labrador, and Vinland is Newfoundland.

On the right, a more “southerly” theory: Helluland is Labrador, Markland is Newfoundland, and Vinland is Nova Scotia.

(Credit: Finn Bjørklid, CC BY-SA 2.5 (left); Nordisk Familjebok, public domain (right)).

The incident is set in the second winter of the expedition, when the Viking settlement is again approached by Natives coming to trade.

Gudrid is inside the palisades with her year-old son, Snorri.

Then:

She was short and wore a shawl over her head.“a shadow fell upon the door, and a woman in black entered.

Her hair was light red-brown, she was pale and her eyes were larger than any ever seen in a human head.

She came to where Gudrid was sitting and said: ‘What is your name?’

“’My name is Gudrid,’ answered Gudrid, ‘but what is yours?’To which the other woman replied: ‘My name is Gudrid.’Gudrid, the mistress of the house, then motioned the other woman to sit down beside her, but at that very moment a great crash was heard and the woman disappeared.”

Encounter with a Beothuk woman

The story might not be as spooky as first reported.

A more recent reading of events suggests the possibility of an encounter between Gudrid and a woman of the Beothuk, the main tribe in Newfoundland at the time.

Perhaps the Native woman was merely repeating what the Viking woman said: Ek heiti Gudridr (“My name is Gudrid”).

This is often what happens first between people who don’t speak each other’s language.

A statue of Gudrid, created for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, now stands at Glaumbær.

The female explorer peers out over the bow of a ship, with the young boy Snorri on her shoulder.

There are two copies of the statue, one at Laugarbrekka (on the Snæfellsnes peninsula), the other in the lobby of the National Archives of Canada in Ottawa.

(Credit: Dylan Kerechuk via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0)

Links :

- “Found Home of the Legendary Viking Woman Who Crossed the Atlantic 500 Years Before Columbus” in Arkeonews

- “The Mystery of the Two Gudrids: A Transcript of First Contact” in American Indian Magazine

- The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman by Nancy Marie Brown

- “Gudrid Thorbjarnadóttir, ca. 985-1050” at Wander Women Project

- The Far Traveler (TV documentary, Danish/English) at DR.TV

- “A Short Biography of Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir for Bostonians,” from McSweeney’s

- Smitrhsonian : Did a Viking Woman Named Gudrid Really Travel to North America in 1000 A.D.?

- The Guardian : Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir … the woman who found the New World 500 years before Columbus

- History Extra : The amazing life of a great female Viking explorer

Tuesday, February 7, 2023

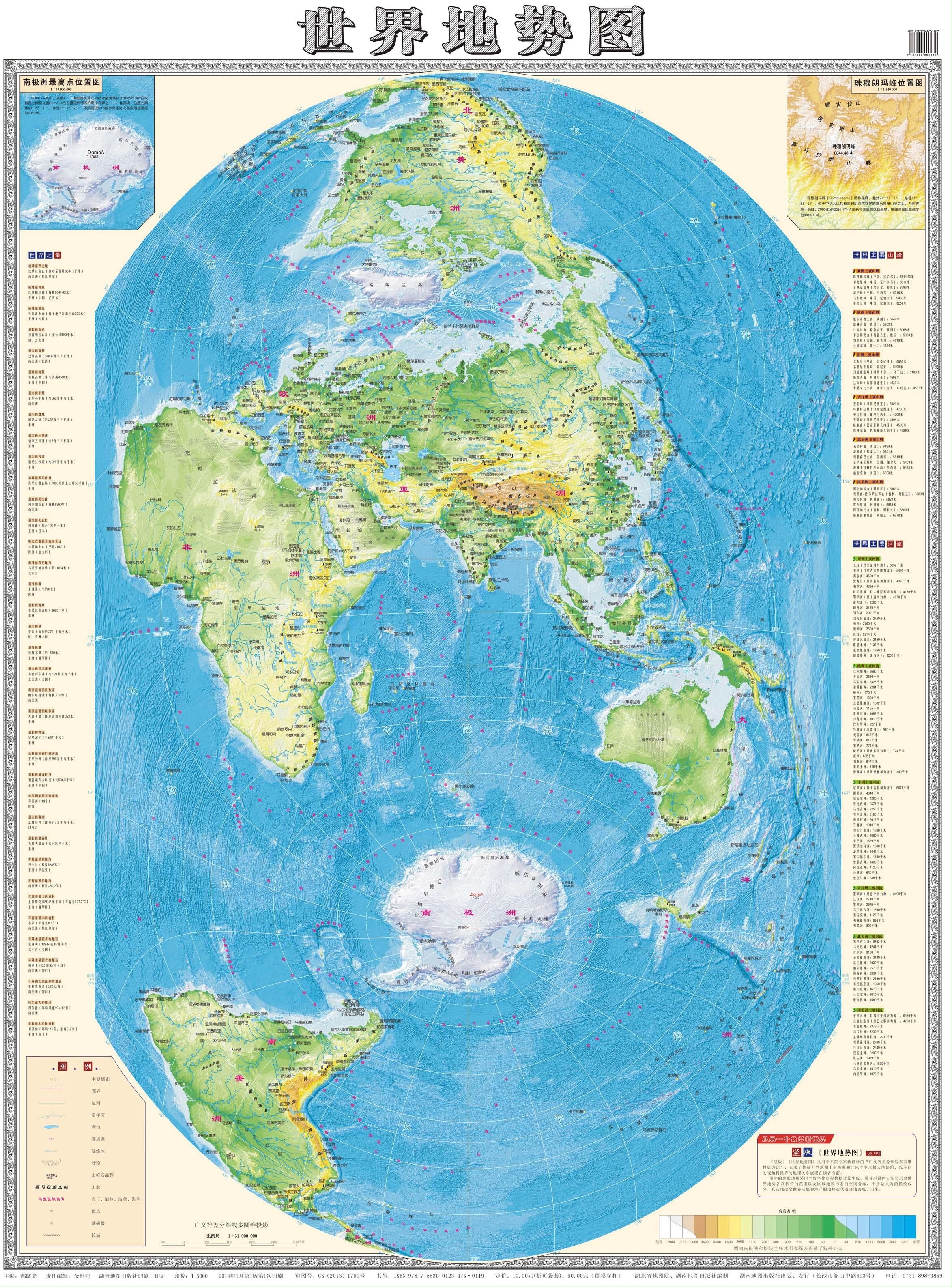

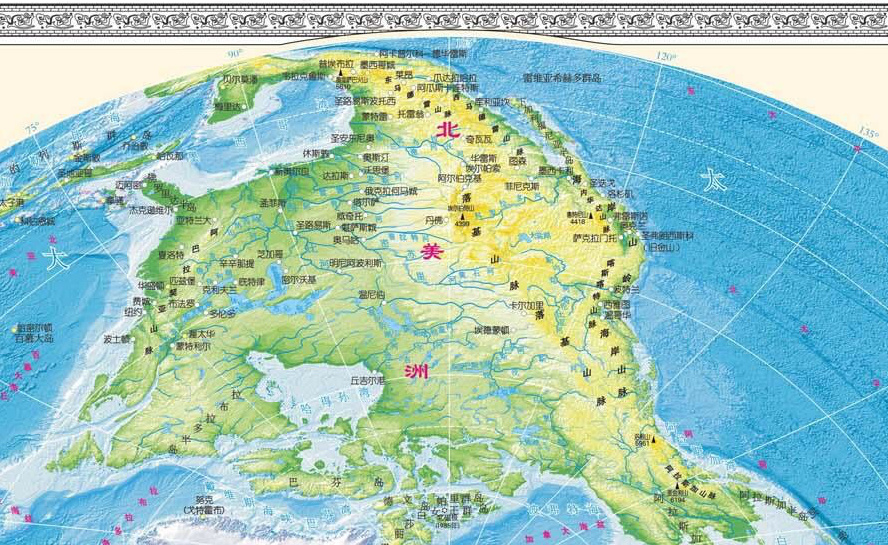

The world map of the future might be vertical

From Big Think by Franck Jacobs

A vertical map might better represent a world dominated by China and determined by shipping routes across the iceless Arctic.

- Europe has dominated cartography for so long that its central place on the world map seems normal.

- However, as the economic centre of gravity shifts east and the climate warms up, tomorrow's map may be very different.

- Focusing on both China and Arctic shipping lanes, this vertical representation could be the world map of the future.

The world, but not as we know it

Europe is tucked away in a corner, an appendage of Asia dwarfed by neighboring Africa.

North America is stood on its head, facing the rest of the world from the top of the map — cut off from South America, which cuts a solitary figure at the bottom.

Africa is justifiably huge, but equally eccentric.

The eye scouts elsewhere for a place to land: not the Indian Ocean, which dominates the middle of the map, but some terra firma.

Antarctica and Australia are too small, mere stepping stones for the land mass of Asia.

Ultimately our gaze is drawn toward China, the lynchpin of this unfamiliar world.

Managing to leave both poles intact, this “vertical” world map is about as far away as you can get from the classic Mercator projection, which slices up both, giving center stage to a puffed-up Europe.

Perhaps this new map will become more familiar soon: It may do more justice to the world of the near future, dominated by China and determined by shipping routes across the iceless Arctic.

China’s ‘ten-dash line’

While there’s no indication that this map represents the Chinese government’s “official” worldview, it is no secret that China has a thing with maps – and more specifically, the country’s representation on them.

In China, the country’s current economic success is seen as a redress of the unequal treatment meted out by western superpowers in the 19th century.

China’s world dominance is a return to a more natural state of world affairs, many feel.

Cartographic rectifications are a symbolically significant corollary of that sentiment.

Fines are regularly imposed on companies – domestic and foreign – that fail to represent China to the fullest extent of its external borders, disputed though they may be by others (e.g.

India, Taiwan and any of the countries with claims overlapping China’s in the South China Sea).

But the People’s Republic’s cartographic obsession doesn’t end at China’s territory itself.

It also includes the country’s position on the world map.

(Credit: Public Domain)

The Kingdom at the Middle of the World

China’s name for itself is Zhōngguó, which means ‘Central State’ or ‘Middle Kingdom’, reflecting its ancient self-image as the civilized center (Huá) of the world, with wild tribes (Yí) at the edge.

That view is not unique to China.

Vietnam, for example, at certain times also styled itself as the “central state” (Trung Quóc) – considering the Chinese in turn as the uncouth outsiders.

It may be surprising to recall, but Europeans themselves once considered their own continent a relative backwater, viewing Jerusalem as the true center of the world.

That changed with the Age of Discovery, which placed Europe at the center of an ever-expanding world.

Maps reflected that worldview, and largely continue to do so.

That’s why today’s standard world map still has Europe at its center – with China off toward the periphery on the map’s right-hand side.

The most notable feature of the very first major modern world map produced in China, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (1602), is that it places China firmly at the center of the world.

Produced for the Chinese emperor by Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, it was the first map ever to combine that perspective with modern western knowledge: it was the first Chinese map to show the Americas, for instance.

That representation may not have taken off elsewhere, but it will be instantly recognizable to Chinese students, as it’s the standard format for world maps in China’s schools today.

(Credit: Prior Probability)

For those used to “classic” Eurocentric world maps, Europe’s marginalization may come across as a bit of an upset.

America’s new position on the horizontal Chinese world map is less jarring: It merely moves from the left- to the right-hand side of the picture.

But then there’s this vertical world map, which deals a similar blow to the American land mass: divided in two and pushed to the upper and lower edges of the map.

Unfamiliar? Sure.

Shocking? Perhaps.

Wrong? Not really.

First off, no world map is totally right, since it’s mathematically impossible to transfer the surface of a three-dimensional object onto a flat surface without some distortion.

And since the world is a globe, where you center that map is a matter of purely subjective choice.

Those choices have historical reasons.

Mercator’s map was not specifically designed to put an inflated Europe at the center of the world.

That was just a side effect; its main purpose was to aid shipping: Straight lines on the map correspond to straight lines sailed on the seas.

(Credit: The Maritime Executive)

The vertical world map, showing the relative proximity of China (and the rest of Asia) to Europe and (even the East Coast of) North America, has a similarly maritime raison d’être, or it will have by mid-century.

Experts project that by 2050 (if not sooner), the Arctic will be sufficiently ice-free to enable the so-called Transpolar Passage, i.e. shipping straight across the North Pole.

That would shave more than three weeks off a traditional sea voyage between Europe and Asia, via the Suez Canal – and even be significantly faster than other northern alternatives like the Northwest Passage (via Canada) or the Northern Sea Route (hugging the Siberian coast).

Since ships would not need to go through locks or pass over shallow waters, it would also remove current restrictions on tonnage per ship.

The only country seriously preparing for such a future: China.

None of the other Arctic powers is giving the Transpolar route any strategic thought.

On the other hand, China’s Arctic Policy document, released in January 2018, already matter-of-factly refers to the Transpolar route as the ‘Central Passage’ – one of several ‘Polar Silk Roads’ that China seems to want to develop.

And they already have the world map to go with it.

- GeoGarage blog : Map orientation: North is not always up

Monday, February 6, 2023

The ocean, a source of treatment for some of the world's worst diseases

From Euronews (link)

The ocean is the cradle of all life on our planet.

Humans have known about its health benefits for centuries.

Today, scientists are going one step further with what they know about its medicinal potential, they are looking in the ocean itself for cures for some of the world's most stubborn diseases.

Part of this search begins in the Algarve, famous for its stunning coastline.

It's in this region that Portuguese biotech company, Sea4Us, is working on a non-opioid analgesic, a safe and effective remedy for chronic pain.

Why pain relief?

Pedro Lima is a neurophysiologist, marine biologist and co-founder of Sea4Us.

He tells us that the need for non-opioid analgesics is enormous, "one out of five of us has suffered from some kind of chronic pain".

His dream is to find in the sea something that can help these people.

Sea4Us was co-founded in 2013 and works on EU-supported projects, collecting and studying simple marine organisms like sponges and other invertebrates.

Scientists from Sea4Us spend their time between laboratories and the depths of the sea, making regular dives for new samples.

Why might marine invertebrates contain the molecules for pain relief?

Many marine invertebrates are stuck in the rock under the sea and they can't move.

Lima tells us that this means they've developed a venom that has "compounds that block the neuroactive signal related to pain".

This is one area of research into simple marine organisms, but they can also be used for a wide variety of purposes, not just healthcare and pharmaceuticals.

Blue biotechnology, biotechnology that uses aquatic organisms, is a fast-growing sector.

In Europe, this market is estimated to grow to around €10 billion by the end of the decade.

It's a whole world of unexplored potential, just waiting to be discovered.

Hidden in the depths

At a depth of around 20 meters, a variety of marine fauna covers the rocky cliffs.

Scientists look there for patterns that could indicate defensive venoms that sponges produce to protect themselves from their neighbours.

Lima describes the questions leading this search as "who eats what? What is avoided by whom? What's the next neighbour?".

The answers to these questions, the relationship between species, is what gives the team the clues as to what to choose.

Pedro Lima, Neurophysiologist, Marine Biologist and Co-founder of Sea4UsThe Algarve, Portugal

Pedro Lima, Neurophysiologist, Marine Biologist and Co-founder of Sea4UsThe Algarve, PortugalInside dark underwater caves, the lack of light means that competition between fauna becomes more specific.

"Sponges don't need to compete against fast-growing species like algae.

They fight between each other and we are interested in that fight", Lima adds.

Protecting the ocean to protect ourselves

Diving at 20 metres or even to the bottom of the sea, you're not safe from plastic pollution.

Despite the fact that two areas in the Cape of Sao Vicente in the Algarve are protected, various waste can be found floating around.

On our dive there, we saw ropes that are evidence perhaps of illegal fishing.

Michał Babiarz is a R&D Scientist at Sea4Us.

He tells us that it's common to find octopus traps, fishing nets, plastic bags and metal cans in these areas.

However, he feels that "as long as we care about the ocean and try to avoid dumping plastics and other litter, we can receive something back from the ocean, from nature, to use for our health".

When scientists collect samples, they take the bare minimum to make sure they preserve populations.

Lima says "the impact is close to zero".

He tells us that the idea is "to be inspired by nature and then we can recreate it, upscale it to industrial scale, so we don't need to go back to the sea to count on the biomass.

The biomass is just inspiration".

The collected samples are taken to Lisbon and studied by the Sea4Us physiology laboratory at NOVA University.

The process can take several months or even up to a few years of work.

Sponges and their symbiotic organisms produce hundreds of individual compounds.

Scientists test them for anti-pain bioactivity and gradually narrow their search.

Silvia LIno, marine biotechnologist at Sea4UsLisbon, Portugal

Silvia LIno, marine biotechnologist at Sea4UsLisbon, PortugalSilvia Lino, a marine biotechnologist at Sea4Us, describes the scientific process to us:

"It's the whole system, it has bacteria, it has a microbiome of its own.

So we just extract and test.

If it's OK, we keep on separating, and we separate as much as we can until we end up with one compound that's responsible for the activity".

So far Sea4Us say they have found two molecules that reduce pain activity in spinal ganglion neurons.

They plan to provide them to the pharmaceutical industry for the next stage: medicine development.

André Bastos, electrophysiologist and co-founder of Sea4Us, says results show that their compounds reduce the level of pain and that they mitigate the risk of developing addiction.

At Sea4Us they're optimistic that the compounds will pass clinical studies and reach the market.

Potential cures of well-known diseases

The ocean could hold cures for some of the worst threats to public health: viral outbreaks, antibiotic resistance, cancer.

Marine research and healthy oceans are some of the priorities of Horizon Europe, an EU programme that funds scientific projects in all the member states.

The CIIMAR Centre in Porto works on several of Horizon Europe's funded research projects and there they are researching a variety of marine life forms, big and small.

They collect cyanobacteria, "ancient organisms and they can grow basically everywhere", Teresa Martins a biochemist at CIIMAR tells us.

Not only can they grow anywhere, but they also contain molecules, chemicals "that might have really interesting applications in the future", she adds.

CIIMAR scientists collecting cyanobacteria on the rocksPorto, Portugal

CIIMAR scientists collecting cyanobacteria on the rocksPorto, PortugalCyanobacteria are known for their potent toxicity, but for scientists, this can be the flip side of medicinal properties.

According to Pedro Leão, a researcher in cyanobacterial natural products at CIIMAR, "any disease could be cured as long as we find a molecule that can treat it".

That's why they look for cyanobacteria "because they produce such a wide variety of compounds that it is possible that we can find an interesting molecule to develop into a medicine".

The scientists at CIIMAR take samples from various countries, isolating and cultivating new species of cyanobacteria.

Their library of over 1000 strains is open to researchers from Europe and from around the world.

Studies show that some of the toxic compounds can precisely target cancer cells, which may pave the way for new therapies.

Experiments on fish larvae show encouraging results that could help in the fight against diabetes and obesity.

Ralph Urbatzka, a researcher in marine biotechnology at CIIMAR believes we are still "a long way from solving the problems of cancer and obesity, but we are on the first line of research to find the solution that can be developed to tackle these diseases".

The future looks promising.

Marine biotechnology could be a sea change humanity needs, but only if we find a way to use its healing potentials without damaging the ocean.

As Vítor Manuel Oliveira Vasconcelos director at CIIMAR says, "life started in the ocean and I believe that our life can be saved by the ocean as well".

Links :

- Euronews : The ocean's microalgae and cyanobacteria: potential cures for disease

- Scientific America : Hope for New Drugs Arises from the Sea

Sunday, February 5, 2023

Iridium GO! exec powered by Certus 100 service

- Navigation Mac : Iridium GO! Exec™ powered by Certus®100 service