Gudrid the Far-Traveled earned her nickname.

She gave birth in America and went on a foot pilgrimage to Rome.

(Credit: Richard Thomson / Richard Thomson Imagery)

The amazing life of “Gudrid the Far-Traveled” was unjustly overshadowed by her in-laws, Erik the Red and Leif Erikson.

- Move over Erik the Red and Leif Erikson, and make room for Gudrid the Far-Traveled.

- She was the first European woman to give birth in America, as well as the first nun in Iceland.

- She roamed Vinland (in modern Canada) and visited Rome.

No medieval woman traveled further than her.

Just after the year 1000 AD, she gave birth to the first European baby in North America.

And she concluded her global odyssey with a pilgrimage on foot to Rome.

Yet few today can name this extraordinary Viking lady, even if they have heard of Erik the Red and Leif Erikson, her father- and brother-in-law.

And she concluded her global odyssey with a pilgrimage on foot to Rome.

Yet few today can name this extraordinary Viking lady, even if they have heard of Erik the Red and Leif Erikson, her father- and brother-in-law.

Dangerous and deadly sea voyages

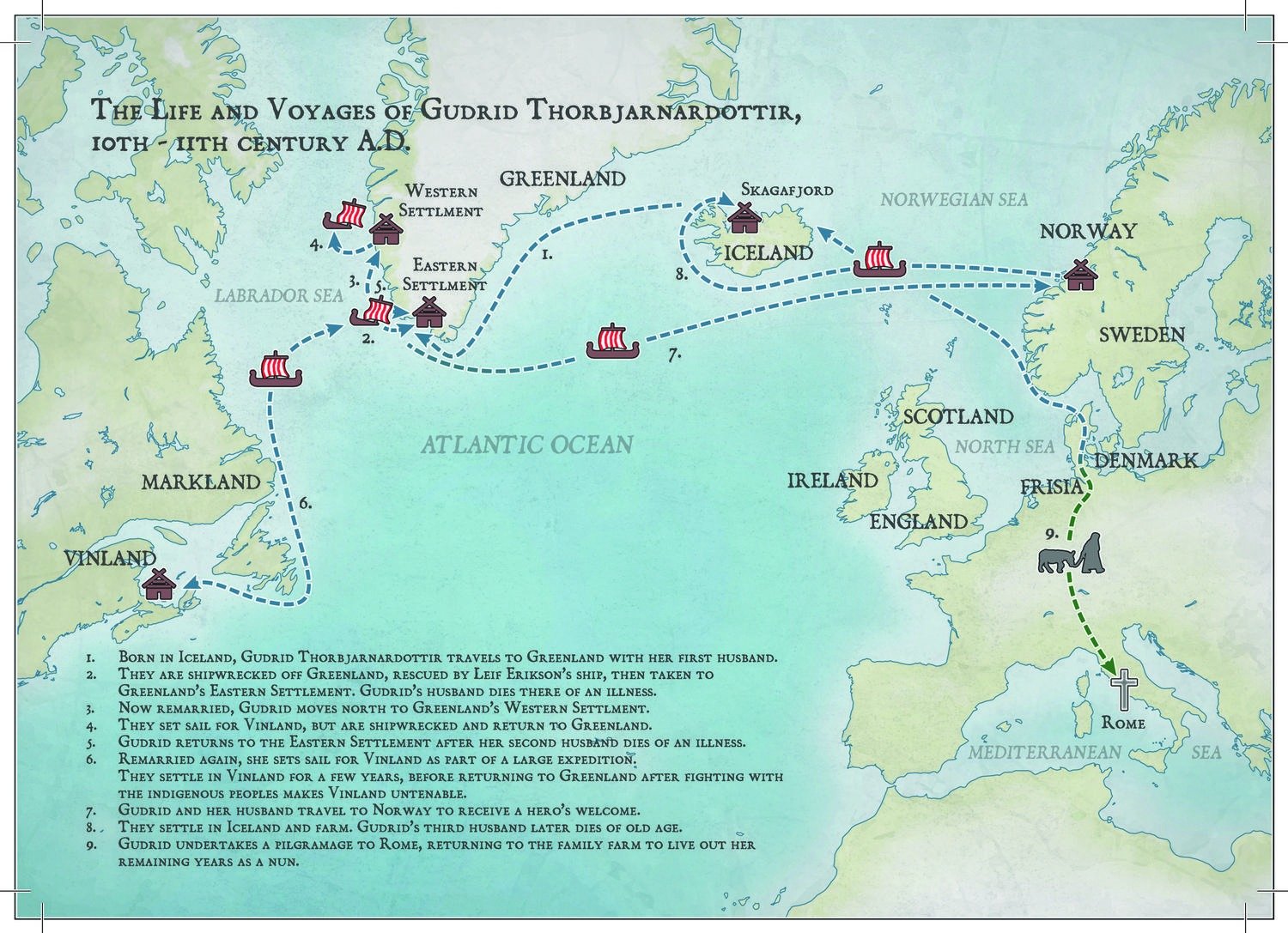

Her full name, in modern Icelandic, is Guðríður víðförla Þorbjarnardóttir — Gudrid the Far-Traveled, daughter of Thorbjorn.

She was born around 985 AD on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in western Iceland and died around 1050 AD at Glaumbær in northern Iceland.

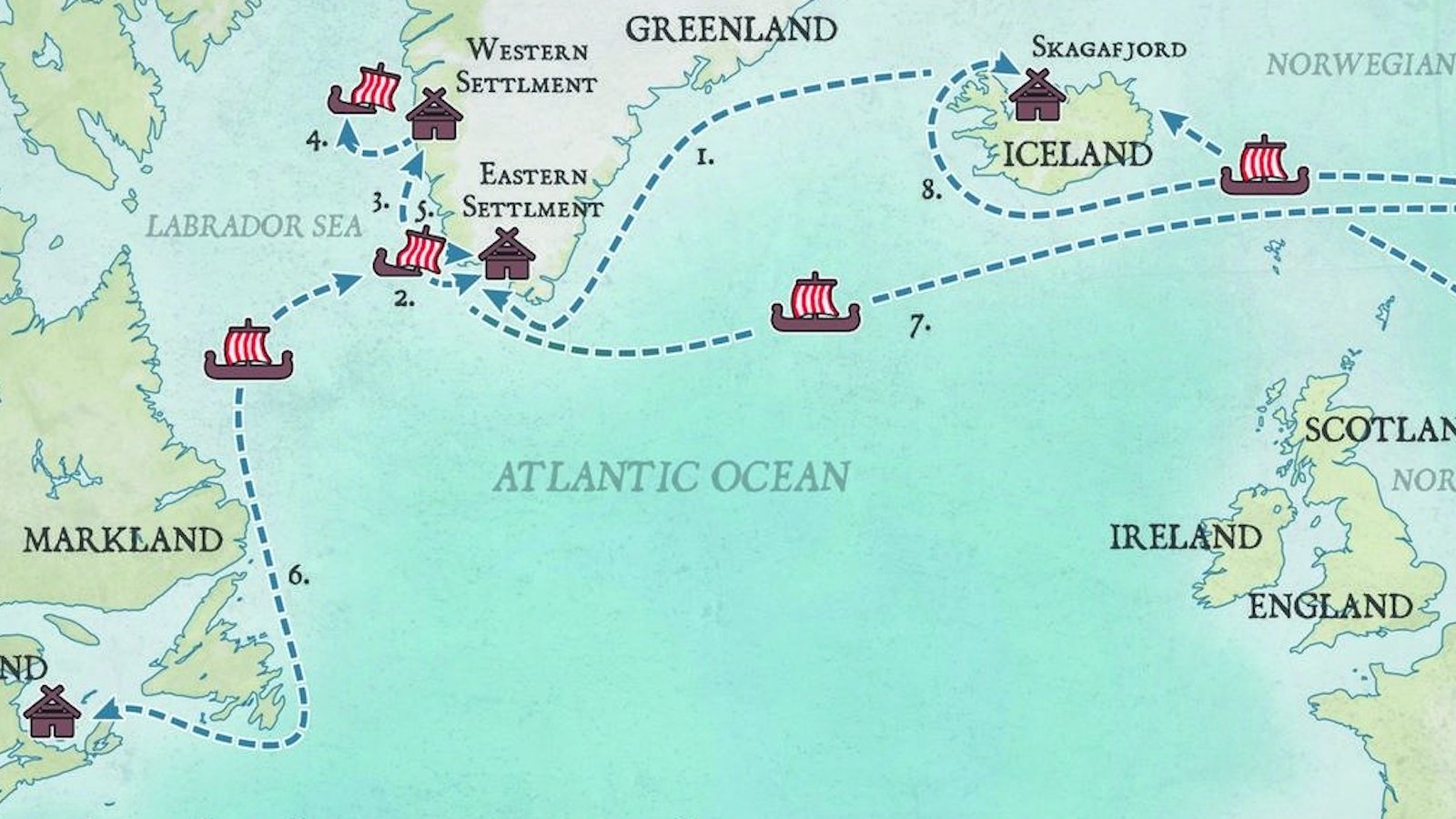

This map shows the extraordinary extent of her travels in between those dates and places.

In all, she made eight Atlantic sea voyages, at a time when those were very dangerous and often deadly.

Her full name, in modern Icelandic, is Guðríður víðförla Þorbjarnardóttir — Gudrid the Far-Traveled, daughter of Thorbjorn.

She was born around 985 AD on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in western Iceland and died around 1050 AD at Glaumbær in northern Iceland.

This map shows the extraordinary extent of her travels in between those dates and places.

In all, she made eight Atlantic sea voyages, at a time when those were very dangerous and often deadly.

Gudrid at sea looking ahead, with little Snorri on her shoulder.

One of three such statues, this one is at Glaumbær in northern Iceland.

(Credit: diego_cue via Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of three such statues, this one is at Glaumbær in northern Iceland.

(Credit: diego_cue via Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 3.0)

What little we know of her comes from the Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders.

These are collectively known as the Vinland Sagas, as they describe the Viking exploration and attempted settlement of North America — part of which the explorers called “Vinland,” after the wild grapes that grew there.

These sagas were told and retold from memory until they were committed to paper in the 13th century.

Due to those 200 years of oral transmission, they likely contain numerous inconsistencies; Gudrid was married twice according to one saga, three times in the other, for example.

Gudrid’s spindle?

Also, they freely mix fact with fiction.

Their pages crawl with dragons, trolls, and other things supernatural.

But the central tenet of the sagas has been proven by archaeology: In the 1960s, the remains of a Viking outpost were dug up at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Among the rubble was found a spindle, used for spinning yarn, which was typical women’s work and thus possibly handled by Gudrid herself.

Her character is so central to the Saga of Erik the Red that some have suggested it should rather be called Gudrid’s Saga.

And in the Saga of the Greenlanders, Gudrid is called “a woman of striking appearance and wise as well, who knew how to behave among strangers.”

Also, they freely mix fact with fiction.

Their pages crawl with dragons, trolls, and other things supernatural.

But the central tenet of the sagas has been proven by archaeology: In the 1960s, the remains of a Viking outpost were dug up at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Among the rubble was found a spindle, used for spinning yarn, which was typical women’s work and thus possibly handled by Gudrid herself.

Her character is so central to the Saga of Erik the Red that some have suggested it should rather be called Gudrid’s Saga.

And in the Saga of the Greenlanders, Gudrid is called “a woman of striking appearance and wise as well, who knew how to behave among strangers.”

That’s a trait that may have come in handy when dealing with the Native tribes of North America, whom the other Vikings dismissively called skrælings (“weaklings”, “barbarians”).

The length and breadth of Gudrid’s travels: as far west as Canada, as far east as Rome — and all just after the year 1000.

(Credit: Richard Thomson / Richard Thomson Imagery)

(Credit: Richard Thomson / Richard Thomson Imagery)

Gudrid’s remarkable story starts when she is around 15, when she travels to Greenland with her father.

According to one of the sagas, she is with her first husband Thorir, who died there the following winter (#1 on the map).

The emigrants suffer terribly on the way to Greenland, with half dying en route and the remainder shipwrecked on a small island off the mainland (#2).

They are rescued by Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red — a friend of her father’s, as it happens.

It is from this event that Leif gets the nickname “Leif the Lucky.” (To this day, Icelanders believe that sea rescues bring the rescuers good luck.)

Gudrid then settles in Greenland (#3) and eventually marries Thorstein Erikson, brother of Leif and son of Erik.

Leif has just returned from a strange new land he discovered across the ocean, and according to one saga, Gudrid joins Thorstein on an unsuccessful trip over to the other side (#4).

A corpse rising from its deathbed

Back in Greenland, the newlyweds spend a winter with Thorstein the Black and his wife Grimhild, whose settlement is decimated by a plague.

Gudrid’s husband is among those carried off by the disease, but his corpse rises from its deathbed to foretell her future: She will marry an Icelander, with whom she will have many children and a long life; she will leave Greenland, visit Norway, make a pilgrimage south, and return to Iceland.

Gudrid returns to Greenland’s Eastern Settlement (#5) and marries Thorfinn Karlsefni, a merchant from Iceland.

At her urging, the two lead an attempt to settle Vinland with a party of 60 men, five women, and some livestock (#6).

In Vinland, Gudrid gives birth to Snorri Thorfinnsson, the first reported birth of a European in the New World.

The year is uncertain, however: anywhere between 1005 and 1013 AD.

The attempt at settlement in America lasts just three years.

Harsh conditions, isolation, and hostile relations with the Natives cause the Vikings to pull back.

When Snorri is three, the family leaves Vinland for Europe.

They receive a hero’s welcome at the royal court in Norway (#7), get rich from selling their exotic goods, and settle in Iceland at Glaumbær farm in Skagafjord (#8).

Back in Greenland, the newlyweds spend a winter with Thorstein the Black and his wife Grimhild, whose settlement is decimated by a plague.

Gudrid’s husband is among those carried off by the disease, but his corpse rises from its deathbed to foretell her future: She will marry an Icelander, with whom she will have many children and a long life; she will leave Greenland, visit Norway, make a pilgrimage south, and return to Iceland.

Gudrid returns to Greenland’s Eastern Settlement (#5) and marries Thorfinn Karlsefni, a merchant from Iceland.

At her urging, the two lead an attempt to settle Vinland with a party of 60 men, five women, and some livestock (#6).

In Vinland, Gudrid gives birth to Snorri Thorfinnsson, the first reported birth of a European in the New World.

The year is uncertain, however: anywhere between 1005 and 1013 AD.

The attempt at settlement in America lasts just three years.

Harsh conditions, isolation, and hostile relations with the Natives cause the Vikings to pull back.

When Snorri is three, the family leaves Vinland for Europe.

They receive a hero’s welcome at the royal court in Norway (#7), get rich from selling their exotic goods, and settle in Iceland at Glaumbær farm in Skagafjord (#8).

Gudrid and Thorfinn in Vinland, as imagined in Our Country: a Household History for All Readers (1877) by Benson J. Lossing. (Art by Albert Bobbett.)

(Credit: The Print Collector / Getty Images)

The family leads a peaceful, prosperous life.

Thorfinn dies of old age.

When Snorri marries, Gudrid goes on a pilgrimage to Rome (#9), apparently by herself and mainly on foot.

When Gudrid returns from her last great voyage to Rome, she finds Snorri has built a church for her, as she requested.

Here, she lives out the remainder of her life in solitude and contemplation: the first nun in Iceland, a final achievement in a unique life.

It is not known when exactly Gudrid died, but she did not die in obscurity.

She established a powerful and influential family.

Among her illustrious progeny were three early bishops of Iceland and a 14th-century compiler of Icelandic sagas, including the Saga of Erik the Red, which mentions his famous ancestor.

Fluid multiculturalism in the North Atlantic

Gudrid’s own ancestors were Gaelic servants of Unn the Wise, a former Viking queen of Dublin who fled to Iceland around 900 AD and settled her followers in an empty valley, Gudrid’s grandfather among them.

It is possible this female pioneer was an example for Gudrid’s own attempt at group emigration.

Two anecdotes from the sagas shed some light on the fluid multiculturalism in the North Atlantic around the year 1000.

At that time, Christianity was starting to make inroads into Viking communities, which however remained largely pagan.

It seems Gudrid herself was an early Christian convert, but not an inflexible one.

At the home of a family friend, Gudrid is the only woman present who knows a “weird song” that will help the prophetess Thorbjorg perform a magic ritual.

At first, Gudrid refuses to sing it, as she is a Christian woman.

But she is easily convinced that it will help everybody present and not harm her status as a Christian.

Gudrid’s own ancestors were Gaelic servants of Unn the Wise, a former Viking queen of Dublin who fled to Iceland around 900 AD and settled her followers in an empty valley, Gudrid’s grandfather among them.

It is possible this female pioneer was an example for Gudrid’s own attempt at group emigration.

Two anecdotes from the sagas shed some light on the fluid multiculturalism in the North Atlantic around the year 1000.

At that time, Christianity was starting to make inroads into Viking communities, which however remained largely pagan.

It seems Gudrid herself was an early Christian convert, but not an inflexible one.

At the home of a family friend, Gudrid is the only woman present who knows a “weird song” that will help the prophetess Thorbjorg perform a magic ritual.

At first, Gudrid refuses to sing it, as she is a Christian woman.

But she is easily convinced that it will help everybody present and not harm her status as a Christian.

And it turns out she has a beautiful singing voice.

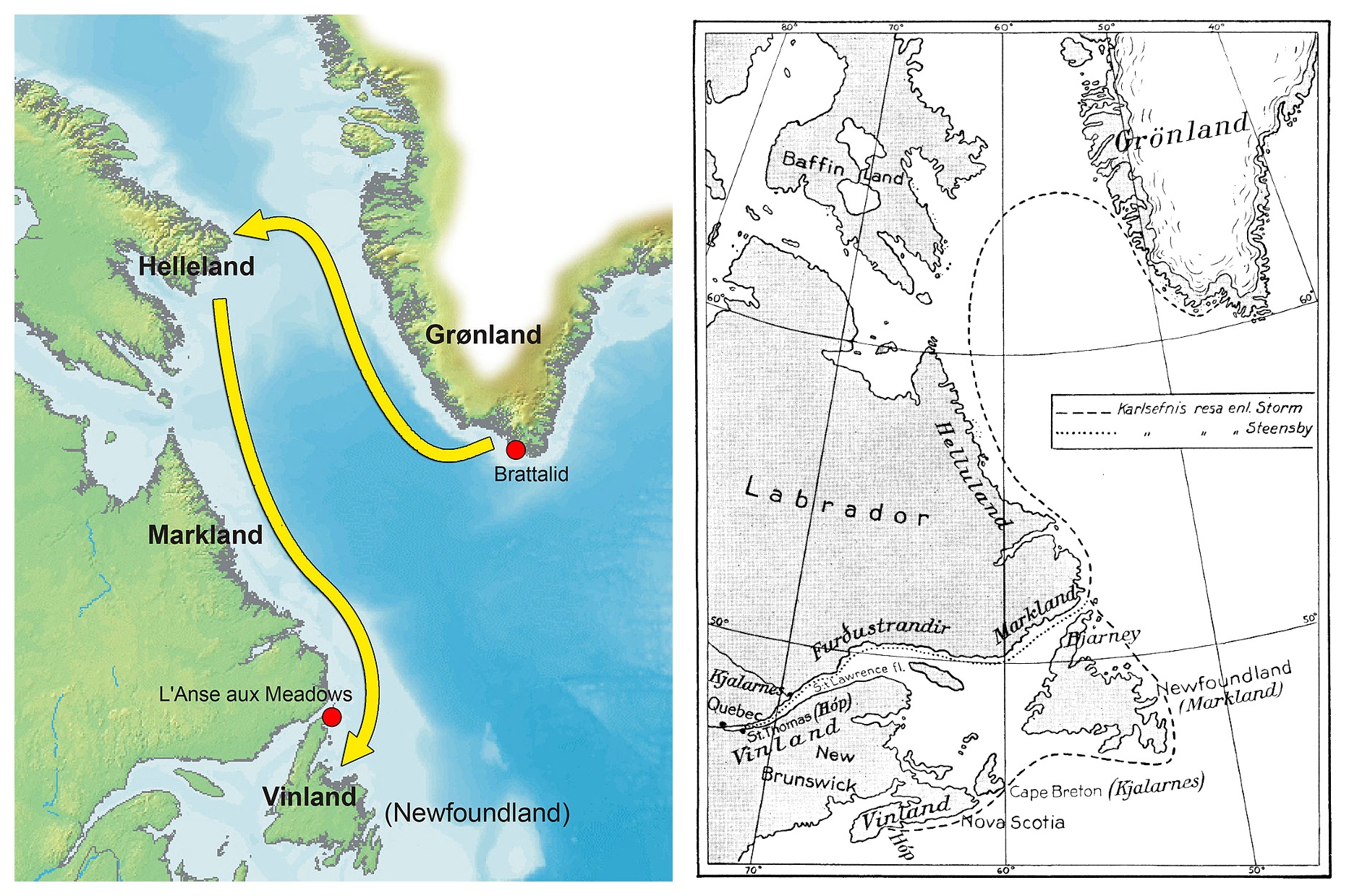

Two theories about Viking exploration in North America.

On the left: Helluland is Baffin Island, Markland is Labrador, and Vinland is Newfoundland.

On the right, a more “southerly” theory: Helluland is Labrador, Markland is Newfoundland, and Vinland is Nova Scotia.

(Credit: Finn Bjørklid, CC BY-SA 2.5 (left); Nordisk Familjebok, public domain (right)).

Another story from the sagas that has mystified readers for centuries because it mentions two “Gudrids” and has traditionally been dismissed as a ghost story could in fact be the earliest recorded conversation between a European and an American.

The incident is set in the second winter of the expedition, when the Viking settlement is again approached by Natives coming to trade.

Gudrid is inside the palisades with her year-old son, Snorri.

Then:

The incident is set in the second winter of the expedition, when the Viking settlement is again approached by Natives coming to trade.

Gudrid is inside the palisades with her year-old son, Snorri.

Then:

She was short and wore a shawl over her head.“a shadow fell upon the door, and a woman in black entered.

Her hair was light red-brown, she was pale and her eyes were larger than any ever seen in a human head.

She came to where Gudrid was sitting and said: ‘What is your name?’

“’My name is Gudrid,’ answered Gudrid, ‘but what is yours?’To which the other woman replied: ‘My name is Gudrid.’Gudrid, the mistress of the house, then motioned the other woman to sit down beside her, but at that very moment a great crash was heard and the woman disappeared.”

Encounter with a Beothuk woman

The story might not be as spooky as first reported.

A more recent reading of events suggests the possibility of an encounter between Gudrid and a woman of the Beothuk, the main tribe in Newfoundland at the time.

Perhaps the Native woman was merely repeating what the Viking woman said: Ek heiti Gudridr (“My name is Gudrid”).

This is often what happens first between people who don’t speak each other’s language.

A statue of Gudrid, created for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, now stands at Glaumbær.

The female explorer peers out over the bow of a ship, with the young boy Snorri on her shoulder.

There are two copies of the statue, one at Laugarbrekka (on the Snæfellsnes peninsula), the other in the lobby of the National Archives of Canada in Ottawa.

Reconstruction of the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows on Newfoundland.

(Credit: Dylan Kerechuk via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0)

(Credit: Dylan Kerechuk via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0)

Links :

- “Found Home of the Legendary Viking Woman Who Crossed the Atlantic 500 Years Before Columbus” in Arkeonews

- “The Mystery of the Two Gudrids: A Transcript of First Contact” in American Indian Magazine

- The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman by Nancy Marie Brown

- “Gudrid Thorbjarnadóttir, ca. 985-1050” at Wander Women Project

- The Far Traveler (TV documentary, Danish/English) at DR.TV

- “A Short Biography of Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir for Bostonians,” from McSweeney’s

- Smitrhsonian : Did a Viking Woman Named Gudrid Really Travel to North America in 1000 A.D.?

- The Guardian : Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir … the woman who found the New World 500 years before Columbus

- History Extra : The amazing life of a great female Viking explorer

No comments:

Post a Comment