courtesy of Nicolas Rapp

From Fortune by Brian Dumaine

The first U.S. offshore wind project is up and running.

Is it a sign of things to come?

It was a brisk Sunday morning in October 2015, and

Deepwater Wind CEO Jeffrey Grybowski’s cell phone buzzed.

His construction manager, who was driving piles 200 feet beneath the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, three miles from Block Island, R.I., said he had to halt work on the company’s wind farm because a humpback whale had meandered near the site.

Under the Endangered Species Act, it’s illegal for humans to “harass” certain marine mammals, and loudly pounding steel into the ocean floor would certainly qualify.

Worse, from Grybowski’s perspective, the law permits driving in piles only during certain months, when the whales aren’t migrating to the area.

Bad weather was moving in, and if his team didn’t finish the project that day, Grybowski would have to wait another six months before the feds would allow him to sink in the final post for the five giant wind turbines that would provide the island’s power.

That meant millions in losses and a disaster for his small company.

Recalls Grybowski: “It was a nail-biting moment.

We had no way of knowing when the whale would stop hanging out.”

Over the next few hours Grybowski hounded his foreman for information.

How far away was the whale? Was it moving at all? Was it drifting closer to the construction site?

By midafternoon, he had only a few hours left to finish before time ran out.

Grybowski’s cell rang again, and he learned that with a magnificent flip of its flukes the humpback had swum away.

The crew then sank the last piling, just making the deadline.

Deepwater Wind's project near Block Island, R.I.

No one ever said it would be easy to build the first offshore wind farm in America.

But in December, Deepwater Wind’s Block Island turbines started spinning out electricity.

What the company accomplished is much more than replacing the island’s dirty, diesel-power plant with clean wind.

The project marked the beginning of what many experts and investors are betting is a boom in offshore wind along the northeast coast of the U.S.

After decades of false starts, bankrupt projects, and protests—Ted Kennedy once complained that a proposed wind farm would ruin the view from his Hyannis Port compound—offshore wind is looking practical.

Europe has been building offshore wind since the early 1990s, but American developers couldn’t figure out how to make those farms compete with cheap coal and natural gas.

In the past few years, however, the turbines have gotten larger and more efficient, and the installation costs have dropped.

As a result, the wholesale cost of European offshore wind power has fallen from an average of 20¢ a kilowatt-hour (kwh) to less than 10¢.

And the cost curve keeps sloping downward.

For the first time, U.S. investors see a path to profitability.

The gold rush has begun.

In the U.S., 23 offshore wind projects totaling 16 gigawatts (GW), the equivalent of about 16 nuclear power plants, are on the drawing board.

Almost all are located along the northeast coast.

Over the past year, Denmark’s oil and gas giant Dong Energy bought federal leases off the coasts of Massachusetts and New Jersey.

Norway’s Statoil won a 33-round auction to secure a 79,000-acre site south of Jones Beach on Long Island for $42.5 million, far more than the $16 million generated by all earlier offshore wind auctions combined.

Shell has been sniffing around.

Wall Street players such as Citigroup (C, -0.15%), HSBC (HSBC, -1.00%), and, as we’ll see, D.E.

Shaw are lining up to finance the most promising projects.

Deepwater Wind is proud to be America’s leading offshore wind developer

t the same time, state governments are generating favorable winds.

Last summer, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, signed a law that requires that state to procure 1.6 GW of offshore wind by 2027.

Not to be outdone, New York’s Democratic governor, Andrew Cuomo, committed to develop 2.4 GW of offshore wind as part of his pledge to get 50% of the state’s power from renewables by 2030 (roughly twice the current percentage).

As Cuomo tells Fortune: “New York will continue to advance the largest offshore wind development in the nation that will bring resilient and reliable power, create jobs, and combat climate change.”

All told, the U.S.

Department of Energy projects that offshore wind will produce 86 GW of power by 2050—about 7% of America’s current electricity demand.

That’s up from virtually zero today.

(Land-based wind now delivers 82 GW in the U.S., vs. just 4 GW 15 years ago.)

If offshore wind can follow such a trajectory, that would make it a multibillion-dollar industry and create as many as 600,000 jobs during the next few decades.

Offshore wind has the long-term potential to produce twice as much electricity as America currently consumes, according to the National Renewable Labs, part of the DOE.

It conservatively estimated offshore wind capacity in the U.S.

by taking into account only areas likely to be developed because of water depth, distance from shipping lanes, and nearness to shore.

But making offshore wind viable in the U.S. won’t be easy.

New projects in the U.S. cost roughly twice the national average of 7.5¢ for all sources of electricity.

One reason is that America doesn’t have the infrastructure and supply chains in place to build offshore wind farms affordably.

In addition, the permitting process is complicated and time consuming, and a new administration in Washington has made it clear that coal—and not renewable energy—will be its priority.

Industry backers argue that offshore wind will follow the same steep cost decline of other technologies.

The price of land-based wind (without any subsidies) plummeted from 14¢ to 4.7¢ a kilowatt-hour from 2009 to 2016, according to financial advisory and asset management firm Lazard.

That’s cheaper than the energy from a new natural-gas or coal plant.

Now we’re seeing the start of a similar downward trajectory for offshore wind.

The DOE estimates that the price of offshore wind will drop by 43% by 2030, which would make it nearly competitive with other new sources of electricity.

Irene Rummelhoff, who runs Statoil’s offshore wind and other “new energy” businesses, is more optimistic: “Two years ago they said European wind wouldn’t be competitive until 2030.

We became competitive last November. In the U.S. it can happen extremely quickly too.”

Deepwater’s small operation off Block Island doesn’t prove that wind power is competitive.

The island had a small diesel plant that was expensive to run.

The wind power replacing it is cheaper than diesel fuel but still more than double the national electricity rate.

But wind power can be competitive in select markets—heavily populated parts of the country where building a new fossil-fuel plant is expensive, if even possible.

In other words, along the Northeast Corridor.

That’s what Grybowski hopes to prove with his next project: building and operating the South Fork Farm, a 90-megawatt (MW) plant—enough to power 50,000 homes—30 miles off the coast of Montauk, and serving the eastern tip of Long Island.

The project, which is slated to come on line as early as 2022, will provide much-needed power when the hedge fund kings and celebrities descend on the Hamptons each summer and thousands of megamansions start drawing outsize loads of power.

Grybowski thinks that if he can get it up and running, it might just provide the gust of momentum the industry needs to take off.

By the look of its bright but cramped office suite in downtown Providence, Deepwater Wind might seem like a shoestring operation run by a band of Birkenstock-wearing environmentalists.

It’s anything but.

The company is principally owned by D.E.

Shaw, a New York hedge fund and private equity firm, which manages $40 billion in assets.

And Deepwater’s chairman, Bryan Martin, is no tree-hugging idealist.

A former partner at J.P. Morgan’s private equity unit, he has decades of experience building huge oil and gas projects and, later, solar and onshore wind farms as CEO of D.E. Shaw Renewable Investments, his current position.

Believing that offshore wind could be the next big economic win, Martin first invested in then-fledgling Deepwater in 2007 and hired Grybowski, a lawyer and a former chief of staff to a Rhode Island governor; Grybowski moved up to CEO in 2012.

Martin saw that Grybowski, an animated, quick-talking executive with an infectious laugh, had the drive to run projects like the Block Island farm, plus the political experience to navigate the complexities of federal and state policies.

(The company is private and will not release financial data.)

Martin and Grybowski saw a huge opportunity to replace aging fossil-fuel plants in New York and New England.

Some of the coal, oil, and nuclear facilities, at 50 to 60 years old, have exceeded their expected lives.

New York State is closing the Indian Point nuclear operation, which supplies the equivalent of 25% of New York City’s power.

Long Island is scheduled to shut three or four of its fossil-fuel plants over the next few years.

But replacing them with new fossil-fuel or nuclear plants, in blue states populated with citizens concerned about clean air and climate change, would be costly and controversial.

When the local utility simply tried to install larger power poles on the leafy streets of East Hampton a few years ago, the public outcry was so great that the power company had to back off.

Says Martin: “We have limited cost-effective options to replace aging power plants in New York and New England.

Offshore wind will be one of the lowest-cost sources of new power.”

Geography is also working in the favor of offshore power.

Finding enough land to build giant solar and wind farms in the heavily populated east, where land values are high, poses a problem.

(The town of East Hampton spent $7 million just to buy the rights to prevent 20 acres from being developed.)

Why not build wind farms in upstate New York, where land is cheap and plentiful?

As it turns out, the state doesn’t have the grid capacity to move the power from upstate to the population centers in the south, and building miles of new high-voltage power lines would face serious local resistance.

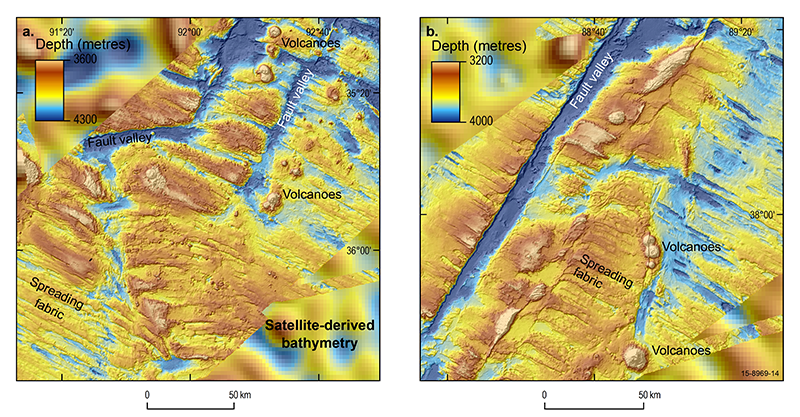

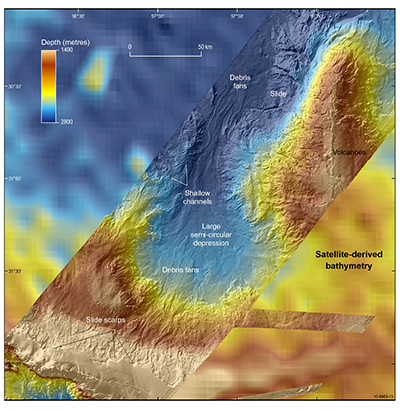

The technology enjoys another advantage in the region: The Atlantic is very shallow—typically 90 feet or less—near the East Coast, making it cost-effective to drive in the pylons that support the turbines.

Plus, the wind blows harder and more steadily there than in many other places.

Offshore wind tends to peak in the afternoon and early evening; onshore wind blows stronger at night.

The biggest demand in summer comes in the afternoon and evening, when the sun is hottest and people return home from work (and the beach) and turn up their air-conditioning.

It’s a perfect match.

The result: a surge in interest from developers.

When the Long Island Power Authority (LIPA), the agency responsible for supplying power to Long Island, asked for bids for the South Fork Wind Farm, some 20 companies, including ones that wanted to build natural-gas and biofuel plants, vied for the project.

Deepwater Wind won the bidding.

Under the 20-year contract, Deepwater will provide LIPA with electricity that will likely cost in the vicinity of 17¢ a kilowatt-hour.

In addition, the project will help LIPA fulfill its pledge to add more renewable energy to the grid.

Says Tom Falcone, the CEO of LIPA: “We hope the South Fork Farm will serve as a gateway project for us.

By starting to develop that resource, the next wind farms will cost a lot less.”

To deliver electricity at that price, Grybowski will have to do some scrambling.

For one thing, building an offshore wind farm requires special ships and equipment.

No such fleet exists in the U.S., and federal law (meant to protect American shipping) prohibits hiring European operations, which have been doing this type of work for years.

Grybowski turned to the fossil-fuel industry.

Because of the slump in oil and gas drilling, many service vessels in the Gulf of Mexico are sitting idle.

For the Block Island project, Grybowski hired Gulf Island Fabrication of Louisiana to build the foundation and another Louisiana company to help install the turbines.

“The Gulf ship owners see offshore wind as a big opportunity,” says Grybowski.

For the South Fork project, the CEO anticipates, he’ll be working out of multiple ports, creating hundreds of jobs.

Little by little he hopes to achieve the scale of the operations in Europe.

Deepwater is already making progress in its quest to cut costs.

The company says the $740 million South Fork farm will be 30% less expensive per unit of energy than the Block Island project.

Prices of turbines are falling, and Deepwater thinks it can obtain permits more quickly this time.

GE-Alstom Block Island wind farm off Block Island, Rhode Island

Offshore turbines boast advantages compared with their land-based brethren.

They are much larger because there is simply more wind to harness over the ocean.

Typically, a landlocked turbine generates 2 to 3 MWs.

The ones Deepwater Wind uses for the Block Island wind farm were made by GE (GE, -1.07%) and crank out 6 MWs.

One project in Europe has deployed 8 MW turbines, the largest in the world, made by Vestas.

Each of the three blades is 265 feet long—bigger than the wingspan of a 787 Dreamliner.

From waterline to the tip of the blade, the turbines stretch 722 feet, more than twice as high as the Statue of Liberty and its base combined.

These behemoths are getting smarter and more efficient.

Because offshore wind turbines are bigger, taller, and in windier areas, they are 50% efficient, meaning that over time they convert half the theoretical wind power into electricity.

That efficiency level is significantly higher than land-based ones.

The giant turbines can rotate 360 degrees, and the blades can tilt to capture the best angle of the wind.

Some experts think that efficiency number could reach 55%, and manufacturers like GE are applying advanced software to do the job.

Says Markus Rieck, managing director of commercial operation, sales, and marketing for GE’s offshore wind business: “Every 1% improvement in efficiency generates a lot of cash for our customers.” In one example, turbines could be designed to communicate with one another.

Those nearest the wind might be blocking the airstream for those in the rear.

GE’s system, still in development, could use algorithms to adjust the angle of the turbines so that the maximum amount of power is produced.

The software can also be used to predict when the turbines are likely to break or need maintenance to avoid sending a worker up—sometimes in horrendous weather—to check what’s wrong.

GE currently uses similar software for its jet engines.

Next up: drones with cameras that could fly up to the turbines to detect material failure, rust, or a missing bolt.

Such technological progress will need to overcome the changed political climate in Washington.

The new administration is unabashedly hostile to renewable energy, and soon after Trump’s Inauguration the White House took down all mention of climate change on its website.

Still, there are good political and economic reasons to support offshore wind.

This fledgling industry is just the kind of heavy steel and construction project that the new President envisions for his infrastructure program.

And offshore could bring a dollop of sorely needed revenue to the Treasury.

The DOE estimates that annual lease payments for offshore wind projects could total $440 million annually through 2050.

Certainly, the Republican-controlled Congress could decline to renew the subsidies that wind power now enjoys.

The production tax credit, which is slated to phase out by 2020, helped the onshore wind industry become competitive and create 100,000 jobs, most of them in red states.

Onshore wind doesn’t need the tax credit any longer, but why not extend it for offshore wind to help create more high-paying jobs more quickly?

Even if Congress doesn’t come through, New York State is looking to provide some financial incentives for offshore wind.

Says John Rhodes, president of Nyserda, the agency that oversees the state’s energy policy: “We want developers to come here with the certainty that they can build the wind farms and sell the power.”

Some help from Washington would be nice, but Grybowski and his investors aren’t counting on it.

They believe they can build out this industry, if they have to, without much in the way of government subsidies.

If they can deal with the endless technical challenges, and even the occasional pesky humpback whale, they just may have the gumption to go it on their own.

Links :