Eunice Foote made an exceptional scientific discovery in 1856 By now, we all know the problems of greenhouse gases.

Burning fossil fuels creates CO2 — with methane sometimes as side product as well — and it traps the sun’s heat.

The result: Global warming, and all the weirding of climate that comes with it.

We moderns have known this since the 80s, when James Hansen testified to congress.

I was 20 years old and read reports of his testimony with a cold feeling of dread.

I remember thinking, shit: I wish society had known this long ago! We should have taken action years ago!

It turns out that we did know.

Sort of!

The basic idea behind greenhouse gases was discovered over a century earlier — by a female suffragette who, in 1856, did some ingenious scientific experiments.

When she wrote up her work, she neatly and pithily predicted the possibility that we’d one day cook the planet.

Eunice Foote was born in 1819 on a farm in Connecticut, and raised in Bloomfield, New York.

In that period of history, few women received good technical educations, but Foote was an exception: Her parents sent her to the Troy Female Seminary, where she learned advanced math and science.

She later became a prominent supporter of women’s rights; a friend of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she was on the editorial board of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first significant suffragist conference.

Foote also was deeply curious about the scientific debates of the day.

Back in the mid 19th century, geologists were uncovering evidence about fascinating shifts of climate in the planet’s past.

By looking at the coal deposits left behind in formerly swampy seas, they figured that Earth’s atmosphere had — for long periods of time — contained considerably higher levels of carbon dioxide.

But,

as the Kent State geologist Joseph D.

Ortiz notes, none of the Victorian-era scientists understood that this increased CO2 would have affected the planet’s temperature.

That’s where Foote came in.

She got intrigued by the question of whether gases can trap heat, and, if so, which gases were most potent at doing this.

So she devised a clever experiment.

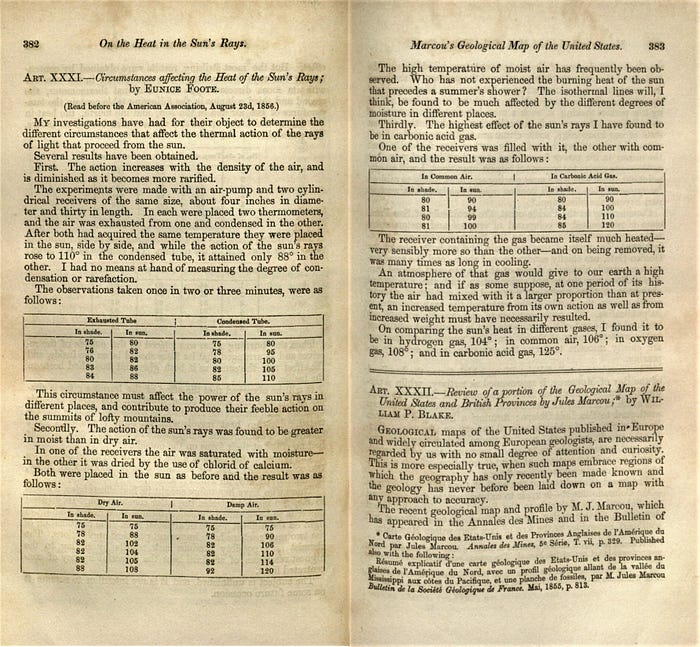

Foote took several glass cylinders and filled them with different combinations of gas: Thin air, thicker air, humid air, and air with “carbonic acid” — what we now refer to as CO2.

She put them in the sun to warm them up, then in the shade to cool them down.

A thermometer inside each jar allowed her to record data on how the gases were affecting each jar’s internal temperature.

Foote made several key discoveries.

The first was that thinner air was less able to trap heat; the cylinder with thin air heated up much less than the one with thicker air.

This, she noted, helped explain a mystery that had long puzzled scientists of the era: Why were temperatures on mountaintops colder than at sea level? Some thinkers had hypothesized that it was because of the angle at which the sun’s rays hit mountain tops.

But Foote’s data suggested a better explanation: The thinner mountaintop air traps less of the sun’s heat.

Even more interesting, though, was the data she gathered from the tube with CO2 in it.

Of all the gases she tested, it was the best at retaining heat.

The glass cylinder with CO2 in it rose to a temperature of 120 degrees F in the sun, fully 20 degrees warmer than the cylinder with regular air.

The C02-filled cylinder also took much longer to cool down.

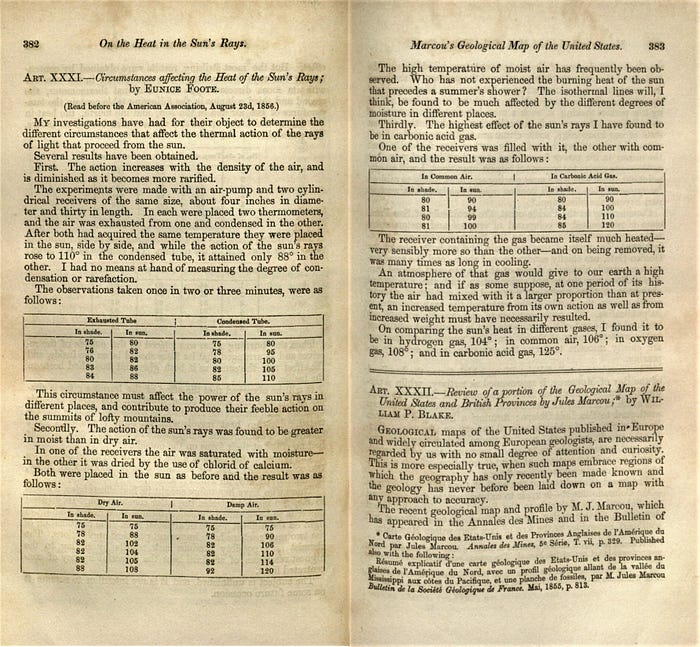

You can

read her original paper here if you want, BTW.

It’s pithy and clear — a model of simple, effective science.

But most interesting is the observation Foote makes at the end of her paper.

She contemplates the way that CO2 lead to a hotter temperature in the glass cylinder, and compared it to the planet …

An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from its own weight must have necessarily resulted.

Boom: In one short sentence, Foote synthesized the impact of greenhouse gases — on a global scale.

More CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere would mean a warmer planet.

Foote was using her data to explain the planet’s past, but but her observations were equally applicable to its future.

“I was floored by the elegance of her experiments,” he says.

“She took what was known from geology, infused it with physical experimentation and helped to create the modern field of climate science.

Alas, as it turns out, it took a long time for Foote to get credit for her remarkable finding.

She wrote up her results in that paper I linked to above, and it was published in the American Journal of Science and Arts in November of 1856.

A few months previously, there had been a scientific conference, and Foote’s husband had presented a paper (on his own experiments on how to amplify the sun’s rays).

But Eunice Foote herself wasn’t able to present her findings: Women were rarely invited to speak publicly at scientific meetings back then.

In her stead, Joseph Henry — a physicist and director of the Smithsonian Institution — presented Foote’s results.

Neither her paper nor the speech appears to have made much an immediate impact; no scientists seem to have picked up on Foote’s paper, or referenced it.

Instead, only a few years later, the well-known Irish scientist John Tyndall replicated Foote’s experiment.

He got similar results — and for over 150 years, he wound up getting the historic credit for being the first to document the greenhouse effect.

Did he copy Foote’s work illicitly?

It seems unlikely.

One of Tyndall’s biographers suspects he hadn’t seen it.

That seems likely to me: Back in the 19th century, when communication technologies were a pale shadow of today’s, it was common for scientists simultaneously to investigate the same question — while being entirely unaware of each other’s work.

(

A phenomenon known as “multiples”.)

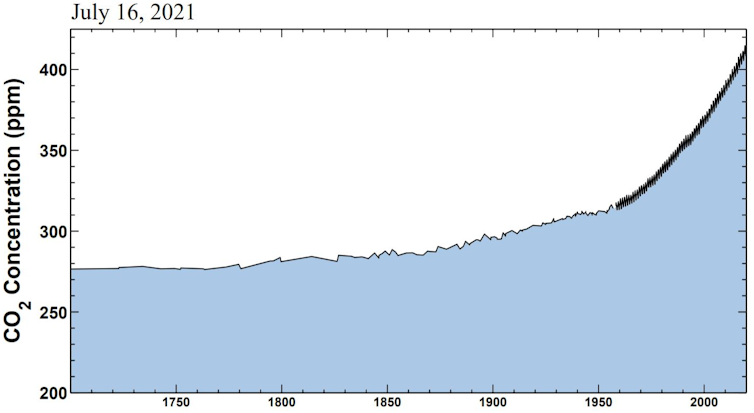

The Keeling curve tracks the changing carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere.

Observations from Hawaii starting in 1958 show the rise and fall of the seasons as concentrations climb.

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Either way, Foote’s work remained lost to history until 2011.

That’s when the retired geologist Raymond Sorensen was looking through his personal collection of old scientific papers.

He found an 1857 report describing the oral presentation of Foote’s work,

and realized in a flash that she’d preceded Tyndall …“It was purely blind luck,” Sorenson says.

“I happened to read that page and knew enough to think, ‘Ah, that doesn’t fit with my understanding of the history of that concept.’”

Sorensen wrote a short paper noting Foote’s life and remarkable work, and pretty soon the academic world took note.

Scholars of science now increasingly credit her role in kickstarting this crucial area of science.

All of which makes me think: Damn, we theoretically knew about the risk of greenhouse gases one and half centuries ago? Ack! Imagine how much more gradually we could have adapted our energy production, if we’d assessed — many many decades ago — the impact of fossil fuels.

But of course, it’s not so simple.

Certainly, Foote and Tyndall and others documented how heat-trapping gases work.

But it wasn’t easy to envision just how rapidly CO2 emissions would ramp up, as the 20th century moved along.

And it really wasn’t easy to imagine all the cascading, complex, interdependent problems that warming climate would cause — like more violent weather, the migration of pests, you name it.

Indeed, scientists who followed in the footsteps of Foote and Tyndall welcomed the warming of the planet due to greenhouse gases.

They hoped it’d make for a better growing season.

Still, it’s impressive as heck to think that Foote predicted global warming so long ago.

Links :