Europe’s Age of Discovery had a little bit of everything – and something for us, too.

Gather ‘round for a story about German bankers, Dutch rebels, Spanish and Portuguese royals, Asian sultanates and English pirates.

Such a cast of actors was surely destined for leading roles in one of the most exciting episodes in the history of shipping: the Age of Discovery.

First, what was being discovered?

Eratosthenes had already proved Earth was a sphere in 240 BCE.

He had even fixed its diameter by calculating from the shadow of a stick in the ground at noon.

Moreover, territories “found” or “claimed” by explorers were already merrily lived in by locals.

What of the Fountain of Youth or El Dorado?

Well, we’re all still trying to find those two.

What was discovered, then?

It distills down to two pillars of civilization: money and law.

From the European perspective, thanks to a few reckless sailors, both took a leap into the unknown.

Spice RoutesThe

ancient Silk Road had, for hundreds of years, been Europe’s way to import Asian spices.

The Roman capital, Constantinople, was in the middle of a winding caravan route that led to China through the sands of the Middle East and the mountains of Afghanistan.

With the capture of Constantinople in 1453 by Ottomans, the Silk Road had a new gatekeeper.

Some suggest Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror’s taxes were so high that it led to ocean shipping doing what it does best: finding a workaround.

Others thought it was just easier to go by water than to walk.

Pindar once sang, “Mortals love potent gold more than all the names of wealth,” and thus the royals of Europe and their hirelings set out to reforge the world’s commercial map.

Portugal had negotiated exclusive right to the eastbound ocean routes to Asia in the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), and that right became valuable when Vasco da Gama bypassed the Silk Road by navigating around the African Cape in 1497.

The Moluccas, located in distant southeast Asia and known simply as the Spice Islands, were transformed into a Portuguese trading post.

All this was made possible by the caravel, the lateen sail, the compass and advanced cartography.

Meanwhile, Spanish treasure fleets had siphoned off Aztec and Incan loot from South America.

Eager to acquire new sources of funding, Spain looked west

In 1520, on a royal commission, Ferdinand Magellan sailed around South America – and the world! – and returned to Europe with 26 tons of cloves and cinnamon in his hold.

Even that was enough to turn a profit!

In the following decades, Spain carried spices from Asia to Europe through Mexico.

The competition irritated the Portuguese, but what could they do?

Portugal was up against a European superpower.

The Spanish Hapsburgs encompassed Germany, Austria and Hungary along with parts of Italy and France.

They had also inherited the Netherlands in 1482.

Trade Wars

But for all of Spain’s dominance and success, the sea dogs were nipping at her heels.

The Protestant Dutch, who resented the Catholic Spanish, rebelled in 1566.

And England’s Queen Elizabeth began issuing letters of marque to privateers like John Hawkins and Francis Drake, who slaved and bartered their way along the West African coast and raided the Spanish Main.

Soon, struggling Spain defaulted on its debts and abandoned its army in the field without pay.

The Dutch seized their opportunity and declared the Republic of the Netherlands in 1579.

The economic hopes of this new country were pinned on its capital, Antwerp.

Goods from around the world were cleared through Antwerp, but the Portuguese role was especially significant.

Since 1501, Antwerp had been Portugal’s clearinghouse for Northern European spice sales.

The Dutch Republic was victorious in battle but could be hurt economically.

Specifically, Spain was maneuvering to absorb its chief rival, Portugal.

Enough Portuguese nobles were frustrated by a succession crisis, in which three grandchildren of King Manuel I had all laid claim to the throne, that they were willing to trade sovereignty for stability.

The last forces loyal to the Portuguese monarchy were crushed at the Battle of Alcantara near Lisbon.

Dom Antonio, who had been made king of Portugal just 33 days earlier, fled with his crown jewels into French exile.

For the Dutch, this turn meant all sea spice routes into Europe were under the control of the Hapsburgs, with whom they were at war.

Having neutralized Portugal, and having recovered its finances, Spain resumed hostilities in the Netherlands.

1584 saw Antwerp under siege.

The city was sacked and reduced in population by over half.

In 1591, the Portuguese redirected their custom to the Fuggers, a German family banking syndicate, and to “in-house” Spanish and Italian firms operating out of Hamburg to distribute spices throughout Central Europe.

To the delight of the Hanseatic merchants on the Elbe River, the Dutch had been shut out.

Just as Spain and Portugal reacted to the fall of Constantinople, the Dutch looked for an alternative when their old suppliers came under strain.

They sent Frederik de Houtman to Java in 1595 to make a bargain with the Bantamese locals, who were persuaded by local Portuguese agents to jack up their prices so high that the Dutch opted to raid Portuguese ships instead.

De Houtman returned to the Netherlands with stolen spices and a big profit, but not until after skirmishing with locals, bombarding the city of Banten and killing a Maduran prince.

Did this chaos hurt?

He proved the Dutch could do damage and still finish off their annual books in black ink.

The English, sensing an opportunity, formed the East India Company on December 31, 1600 under the auspices of a royal charter granted by Queen Elizabeth.

The Netherlands wasted little time, birthing the United East India Company (VOC), better known as the Dutch East India Company, in 1602.

The game was afoot.

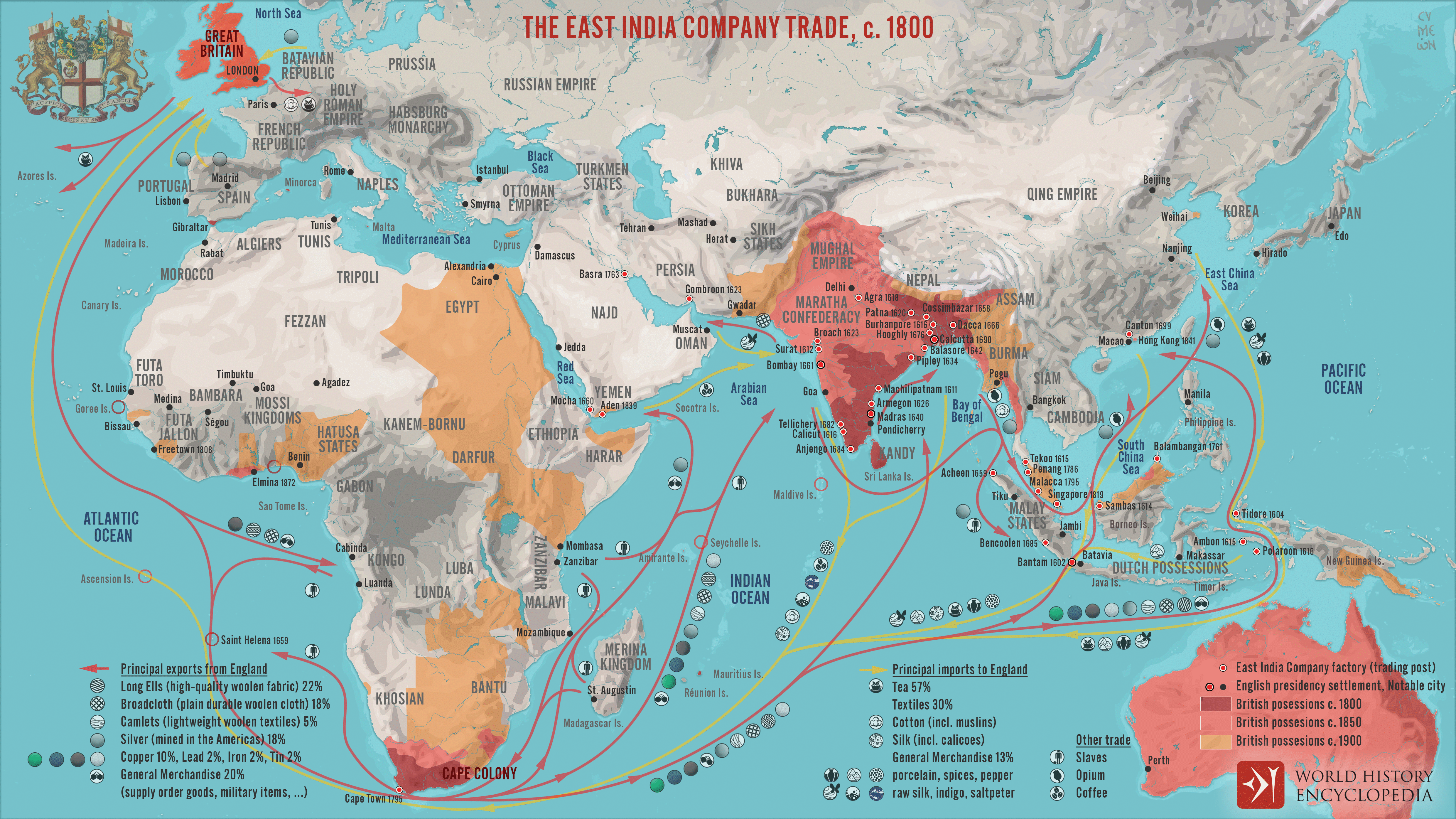

A map illustrating the markets and goods traded by the East India Company (EIC) with East and Southeast Asia and India around 1800.

Incorporated on December 31, 1600, by Queen Elizabeth I's Royal Charter, it was given an initial 15-year monopoly on English trade from the Cape of Good Hope eastward to the Straits of Magellan.

By 1620 the Company had twelve trade outposts (factories) and by 1700, was making close to thirty annual sailings to the Far East, had its shipbuilding yard, a fleet of 10,000 tons, more than 2,500 seamen, and, by 1803, a private military force of 260,000 men and was responsible for almost half of all of Britain's trade.

Modern InnovationsImagine a simpler world – without stock exchanges, corporate governance or angry shareholders.

Many of these innovations originate with the

Dutch East India Company.

Famously, it held the world’s first initial public offering.

The VOC charter stated in Article 10 that all “residents of these lands may buy shares in this Company,” with no minimum or maximum.

These were held in a registry and could be bought or sold by the shareholders in a stock market.

What’s more, shareholders’ liability was limited to the capital they had committed to the VOC.

For all its innovations in company law, the VOC also made a contribution to maritime law that is broadly valid to this very day: Without fast communications, decentralization was necessary to sustain operations straddling far-away continents.

Ship captains were deemed “agents” of the VOC, which is a legal fiction still found in many Continental statutes.

For example, the German Commercial Code states that the captain is an “agent of the owner” and the Dutch Civil Code includes numerous provisions affording the captain a similar authority.

The English East India Company, though it relied heavily its royal charter, also made contributions to the understanding of legal personhood – meaning a corporation should be treated as a self-sufficient, self-contained entity with its own rights and duties.

And by its operations in multiple countries and its exercise of quasi-sovereign powers, e.g., by instigating its own military conflicts with local powers or by minting its own coinage, it afforded the English legal system its first stress test against the kaleidoscopic problems posed by multinational corporations.

As excellent as the VOC’s legal innovations were, its commercial legacy is mixed and its reputation deeply marbled by behavior that today would be considered totally wrong.

Further, as awestruck as Europeans were by the profits from trading with Asia, from the Asian perspective trade with Europe was only a small fraction of their overall commerce.

The markets of China, Japan, Arabia, India, Java and Malaysia were already part of a vast network to which Portugal and Spain and then, subsequently, the Netherlands and England had just gained access.

What made this moment different from before was that the middlemen had been cut out.

Despite its flaws, the VOC’s legacy has endured.

In 2006, Dutch Prime Minister Jan Balkenende, advocated for a revival of the “VOC mentality” – a mentality that would, presumably, at this point be more than four centuries old and which he associated with optimism, resilience and risk-taking.

The comment drew its share of criticism, of course.

The English East India Company, meanwhile, has found its own weird afterlife as a London-based luxury goods brand.

From the Age of Discovery to Self-Discovery

Wrestling with these contradictions and curiosities will keep historians busy.

Anything as complex as the Age of Discovery will inevitably undergo its own process of exploration – with moral questions, facts and interpretations always emerging.

It’s up to each of us to decide whether to remain open to the many inspirations history can offer or simply accept that the East India Company should maybe be just a cute place on New Bond Street where we can buy that fancy new purse.

Who knows?

Perhaps what you just read will launch your own Age of Discovery.

“Be what you are, once you have learned what that is,” to quote Pindar again.

Links :

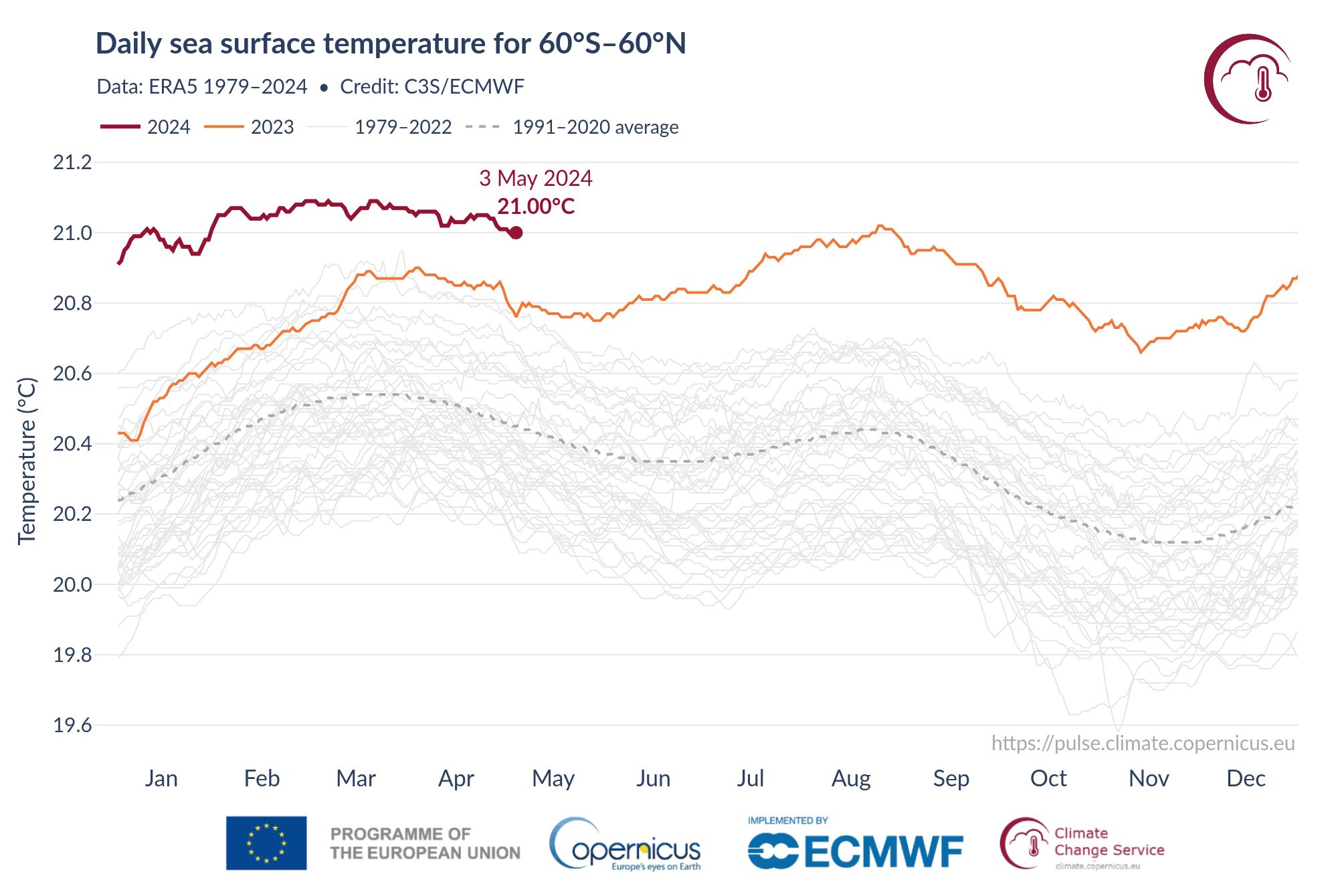

Hurricane Idalia approaching the western coast of Florida while Hurricane Franklin churned in the Atlantic Ocean at 5:01 p.m.

Hurricane Idalia approaching the western coast of Florida while Hurricane Franklin churned in the Atlantic Ocean at 5:01 p.m. When observed from space, as exemplified by this view from the Moon, the Earth appears predominantly blue.

When observed from space, as exemplified by this view from the Moon, the Earth appears predominantly blue.

Figure 1: The Irish Shelf Seabed Geomorphological Map (ISSGM) version 2023 as it appears online, in Ireland’s Marine Atlas.

Figure 1: The Irish Shelf Seabed Geomorphological Map (ISSGM) version 2023 as it appears online, in Ireland’s Marine Atlas. Figure 2: An example of bedrock outcrops (in colour) ‘filtered out’ of a DEM (black and white bottom layer).

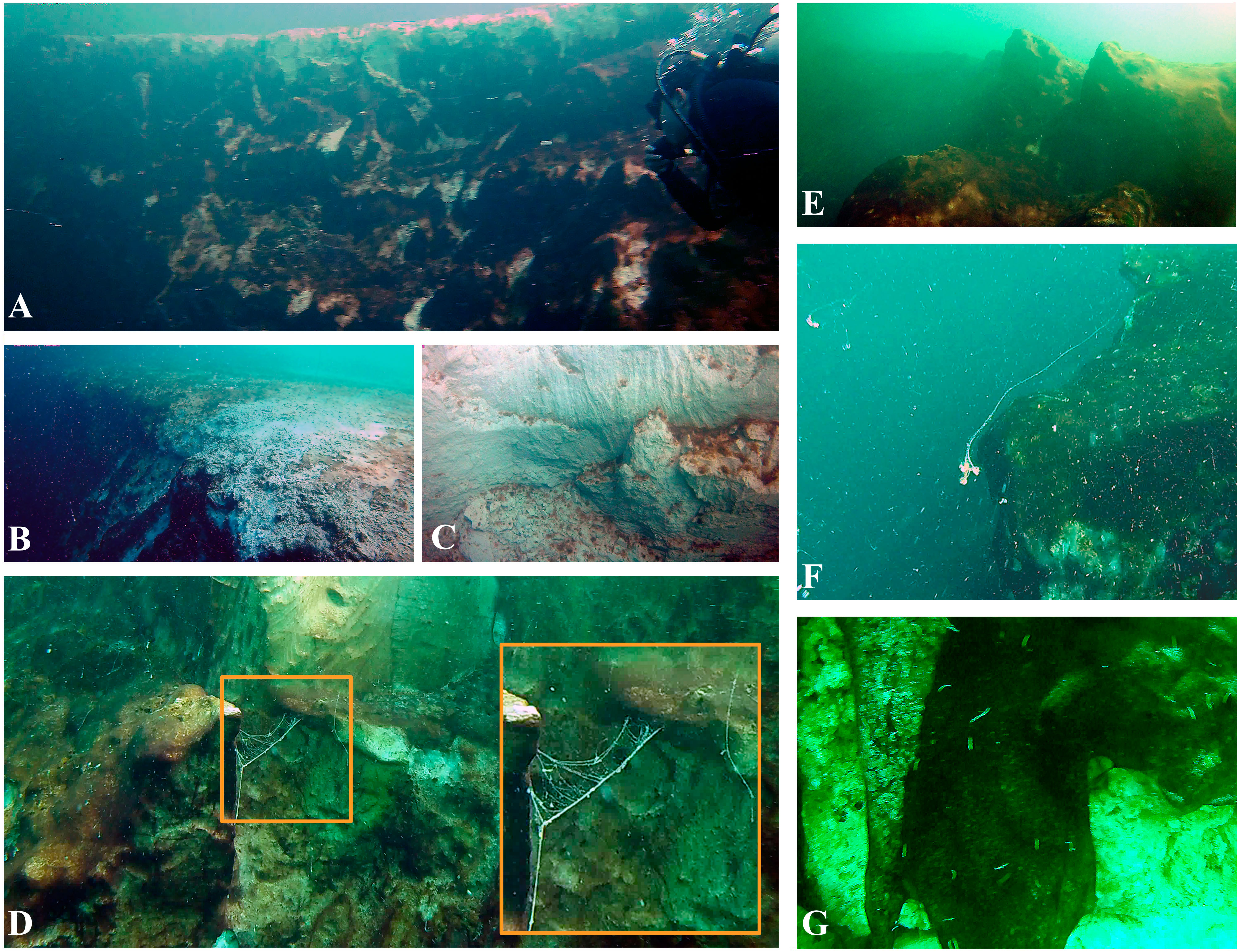

Figure 2: An example of bedrock outcrops (in colour) ‘filtered out’ of a DEM (black and white bottom layer). Figure 3: Examples of landforms from the four nominal regions on the Irish shelf.

Figure 3: Examples of landforms from the four nominal regions on the Irish shelf.