Credit: Gallo Images/Orbital Horizon/Copernicus Sentinel Data 2021

From Inside Climate News by Bob Berwyn

The inexorable rise of ocean heat is now evident off the coast of West

Antarctica, potentially disrupting critical parts of the global climate

system and accelerating sea level rise.Research scientists on ships along Antarctica’s west coast said their recent voyages have been marked by an eerily warm ocean and record-low sea ice coverage—extreme climate conditions, even compared to the big changes of recent decades, when the region warmed much faster than the global average.

Despite “that extraordinary change, what we’ve seen this year is dramatic,” said University of Delaware oceanographer

Carlos Moffat last week from Punta Arenas, Chile, after completing a research cruise aboard the RV Laurence M.

Gould to collect data on penguin feeding, as well as on ice and oceans as chief scientist for the

Palmer Long Term Ecological Research program.

“Even as somebody who’s been looking at these changing systems for a few decades, I was taken aback by what I saw, by the degree of warming that I saw,” he said.

“We don’t know how long this is going to last.

We don’t fully understand the consequences of this kind of event, but this looks like an extraordinary

marine heatwave.”

If such conditions recur in the coming years, it could start a rapid destabilization of Antarctica’s critical underpinnings of the global climate system, including ice shelves, glaciers, coastal ecosystems and even ocean currents.

Such radical changes have already been sweeping the Arctic, starting in the 1980s and accelerating in the 2000s.

Data collected during Moffat’s most recent research voyage includes the first readings from temperature and salinity sensors that were deployed a few years ago, which will give the scientists a starting point for comparisons.

Moffat said it’s “too early, and difficult” to attribute this year’s conditions to long-term climate change until some peer-reviewed results are published.

“But it seems to me that this might be a really unprecedented event,” he said.

“These episodes of relatively rapid ocean warming that can persist for months have been occurring all over the place.

They haven’t been common in this region.”

He said ocean temperature readings going back to April 2022 speak to the persistence of the warm conditions off the Antarctic Peninsula.

The cruise covered an area more than 600 miles long and criss-crossed waters above the 125-mile wide continental shelf, documenting widespread ocean heating.

“That’s a very significant region,” he said.

“We don’t have data going back 30 years for the entire region.

But for the parts of the shelf for which we do have that data, it really seems extraordinary.

It’s very

difficult to warm the ocean, and so when we see these conditions, that really speaks to a very intense forcing.”

A Dangerous Climate FeedbackGreenhouse gases, mostly from burning fossil fuels, are the force behind the warming of the atmosphere and the oceans.

The latest reports from Antarctica raise concern that a perilous climate feedback cycle of warmer oceans and melting ice has started around the continent, said

Johan Rockström, director of the

Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

“We know

the melting of Antarctica is most sensitive to lubrication by water,” he said.

“It’s the sea melting the ice from below, it’s not atmospheric melting from above.

And this is really, really worrying … and quite surprising, because up until 10 years ago, we were absolutely convinced that the Greenland ice sheet and the Arctic was the more sensitive of the two poles.”

Up until about 2014, science suggested that Antarctica was still gaining ice, but “that has shifted,” he said.

An

assessment released that year by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that there is likely an Antarctic tipping point between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius warming that would trigger irreversible melting of ice shelves and glaciers.

The

Paris Climate Agreement to cap warming in that range was signed the following year with the understanding that a vicious climate cycle in Antarctica has global implications, raising sea level faster than expected, and contributing to the slowdown of the critical Atlantic thermohaline circulation that moves warm and cold water between the poles.

He said

research shows that system of currents has been affected by global warming in recent decades, leaving more warm water in the Southern Ocean to drive marine heatwaves.

Instead of flowing northward to the Gulf Stream, the warmer water persists around Antarctica, because ”That whole system has slowed down by 15 percent,” he said.

“So when the circulation slows down, and you have more heat, you get more warm surface water in Antarctica.”

The Potential Start of an Icy Death SpiralAntarctica was seen as a frozen redoubt until very recently because its ice sheets average more than a mile thick and cover an area as big as the contiguous United States and Mexico combined, spreading over about 5.4 million square miles with its center more than 1,000 miles from the ocean.

The continent is also encircled by a swift ocean current—the only one that flows

all the way around the world–and an accompanying belt of jet stream winds several miles above it.

Both helped buffer Antarctica’s sea ice, as well as its land-based glaciers and floating ice shelves, from the rapid increase of climate extremes seen in most other parts of the world the past few decades.

But the observations from this year’s conditions may bolster several recent studies showing how global warming is eroding that protection.

An August 2022

study in Nature Climate Change suggested that “circumpolar deep water” at a depth of 1,000 to 2,000 feet has warmed by up to 2 degrees Celsius, which is in turn related to a poleward shift of the westerly wind belt.

That’s a critical depth where the

water creeps up the continental shelf and beneath the floating ice shelf extensions of Antarctica’s huge land-based ice sheets, which poses a threat not only to ice in West Antarctica, already known to be vulnerable, but also to the thick, remote ice on the eastern half of the continent.

Warming through the world’s oceans is projected to persist in coming decades, so “the oceanic heat supply to East Antarctica may continue to intensify, threatening the ice sheet’s future stability,” the authors of the 2022 paper wrote.

Another

study, published June 2022 in Science Direct, showed that the changes to the winds responsible for pushing the warmer water closer to shore will also persist if greenhouse gas emissions continue, so without immediate action to implement global climate policies, the Antarctic system could loop into a death spiral.

A 2016

study outlined a worst-case scenario in which warming would contribute to a rapid break-up of towering ice cliffs near the shore in a process that could speed up sea level rise, raising the water up to 7 feet by 2100 and 13 feet by 2150, increases that would be very hard to adapt to.

The water’s rise is already accelerating.

In the 1990s, the global average sea level increased at about 3 millimeters per year, but that annual rate increased to 4.5 millimeters in the last five years.

Between August 2020 and January 2021, sea level rose 10 millimeters.

Warming Waters Spread South

Researchers feel those buffering winds and ocean currents when they start their research voyages from South America, Africa or Australia because they have to cross the “Roaring Forties,” latitudes where fierce winds and deck-washing waves toss the vessels for a day or two before they end up in the relative calm of the Southern Ocean, where they can cruise smoothly under misty skies past floating sheets of ice.

The Southern Ocean encompasses all the water below 60 degrees South, and while it’s a mix of Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean waters, it was geographically recognized as a distinct geographic entity by NOAA in 1999, precisely because it’s separated by those currents in the ocean and the sky that enclose Antarctica’s climate and ecosystems.

But it’s now clear that warming is dangerously infiltrating West Antarctica, said

Rob Larter, a polar marine scientist with the

British Antarctic Surveywho is currently measuring marine sediments in the Southern Ocean from the

RV Polarstern to determine how fast and how far ice sheets have moved in the past.

Comparing the marine geology with climate data like temperatures and carbon dioxide levels through the millennia helps show how the ice will respond to human-caused warming, but some of the changes are visible without instruments, Larter said.

“The most striking changes I have witnessed are the retreat of the front of Pine Island Glacier after an abrupt change in its calving style in 2015,” he said, describing one of the glaciers in West Antarctica known to be particularly vulnerable to the warming ocean.

Up until that year, the glacier had been thinning, and then all of a sudden, big chunks started breaking off, he said.

“I visited the front on three different research cruises, in 2017, 2019 and 2020,” he said.

“And each time we had to go about 10 km further upstream due to the rapid retreat resulting from more frequent calving.”

RV Polarstern in a nearly ice-free Bellingshausen Sea

(Photo: Daniela Röhnert).

The RV Polarstern is cruising in the Bellingshausen Sea, farther south than Moffat’s ship, but Larter said the ocean surface in their research area is also unusually warm, “largely a consequence of the fact most of the sea ice that’s usually here had melted or drifted away westward by the end of November,” he said.

Sea ice holds the water temperature to about 2 degrees below zero Celsius, Larter said, but the water during his current expedition has been nearly a degree above zero—almost three degrees Celsius warmer than normal.

He said declining sea ice could potentially affect the global ocean temperatures more rapidly by decreasing the flow of frigid water from the Southern Ocean along sea floors farther north

“The dense, cold water formed around Antarctica flows northward and fills the deepest parts of most ocean basins,” he said.

“In doing so it provides an important driver for the overturning thermohaline circulation.”

Those currents help balance the global climate by redistributing massive amounts of heat energy.

The process of producing that dense water starts with sea ice formation and melting, he said.

“Sea ice is a little fresher than the water it forms from due to brine rejection during ice crystal formation,” he said.

“The residual water becomes more saline, which makes it denser, causing it to sink, where it keeps the global refrigerator running as it spreads outward.”

It will be critical to monitor exactly how and where the warming ocean moves toward the ice shelves in West Antarctica, said Ted Scambos, a senior Antarctic researcher with the Earth Science and Observation Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

For now, it’s not clear whether the warmer water will reach the Amundsen Sea,

which holds the Pine Island Glacier and Thwaites Glacier,” he said.

“If it does, or if it’s the start of a patch of warm water that will eventually drift in front of all of those glaciers, then, yeah, we would see a jump in the retreat rates for sure.”

Scambos helps coordinate

a global effort studying the region’s most vulnerable ice, and he said the scientists are also probing and prodding far beneath the shelves to learn how the formation of grooves and cracks affects melting.

Sometimes, as the shelf drags across sections of the rough seafloor, the friction opens up gaps that can trigger more crack as the ice sags from above.

“The processes are real,” he said.

“They really do happen, they really do speed things up and they are being incorporated in the models.

But it’s not as dire as some of the more high end forecasts.”

While the tipping points that could cause

runaway ice melt are difficult to reach, he said, research like Larter’s sediment maps shows that rapid retreats and meltdowns have happened in the geological past, potentially raising seas 2 to 3 meters in a century to submerge coastlines around the world.

“The runaway aspects of the process take hold fairly slowly.

In the natural world, this process of marine ice instability takes about a millennium,” he said.

But, “if we continue to drive it hard by warming the Pacific, by changing the circulation of air and ocean around Antarctica, we will get the fastest possible version of that marine ice sheet instability.”

Links :

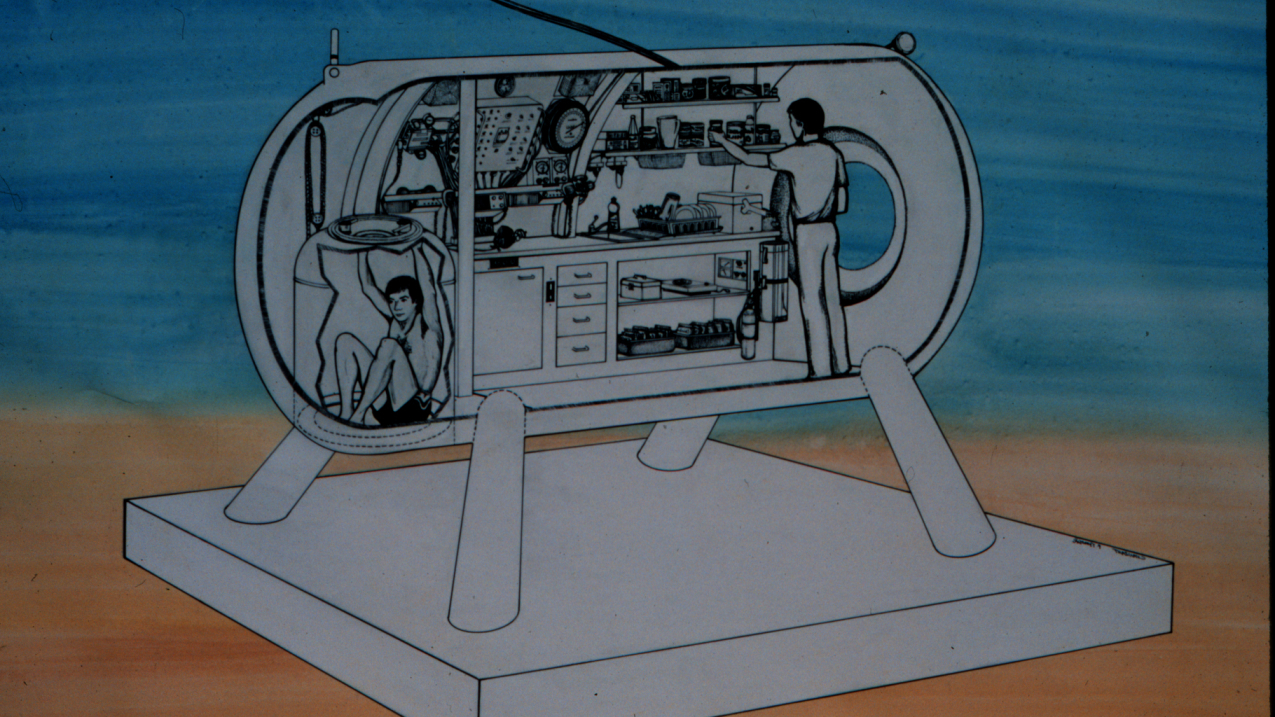

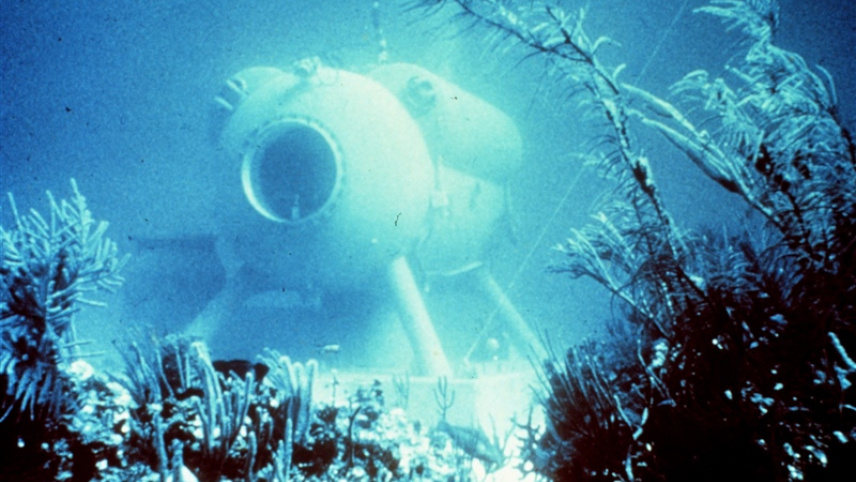

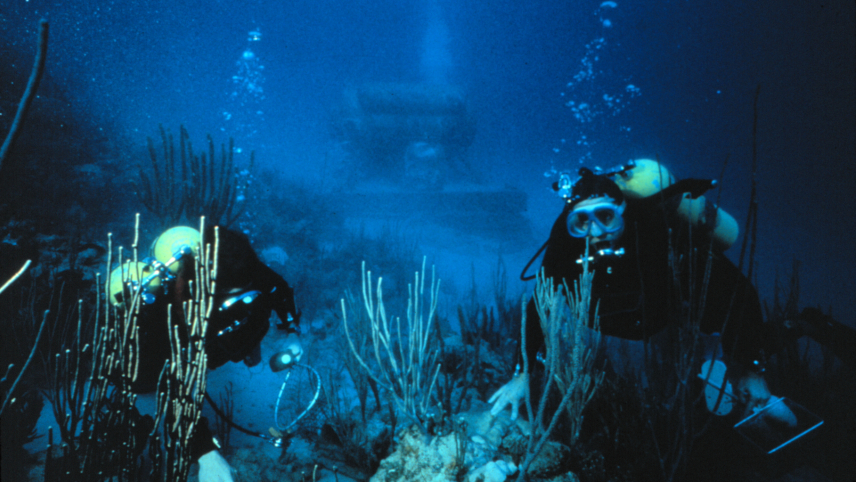

NOAA's HYDROLAB, based in the Caribbean beginning in the mid-70s, was an underwater lab for researchers.

NOAA's HYDROLAB, based in the Caribbean beginning in the mid-70s, was an underwater lab for researchers.

Four scientists inside the NOAA Hydrolab as it sits on the ocean floor, with two more scientists in SCUBA gear looking in through a window on the end of the structure.

Four scientists inside the NOAA Hydrolab as it sits on the ocean floor, with two more scientists in SCUBA gear looking in through a window on the end of the structure.