photo : Tor Johnson

From YachtingWorld by Elaine Bunting

Preparations for the voyage from the Caribbean to Europe need to begin before you leave home, but what should you consider?

By early summer the peak Caribbean season is coming to a close, ushered out by a fusillade of big regattas.

Then, with summer returning to the northern latitudes, crews begin the return leg of their migration back home.

While most people focus on

crossing the Atlantic from Europe to the Caribbean, the voyage back to Europe or the US east coast is equally important – in some ways more so.

The road home can be more testing, but it is also varied, and planning for it should ideally shape your preparations from the time you plan to leave home for a season in the sun.

What should you weigh up in your crew and boat preparations and which route and strategy is best?

You could, of course, always take the easy way out – remember that old saw that nothing goes to windward quite like a 747!

You could get your boat sailed home by a delivery crew, or shipped back to the Mediterranean or northern Europe.

These options, once the preserve of big motorboat owners and superyachts, are gaining popularity with mainstream cruisers, especially the time-pressed – in fact, a couple of owners I interviewed at the Caribbean 600 this year had their yachts shipped out from Europe and had booked them back by ship later in the season.

Nevertheless, each year, around 1,000 yachts arrive in Horta en route to Europe (the total was 1,232 in 2015, to be exact).

Yachts mainly stop here in May and June and around half have come direct from a Caribbean island, while a majority of others arrive via the staging post of Bermuda.

According to a survey by Jimmy Cornell: ‘every year approximately 1,200 boats cross the Atlantic from the Cape Verdes, Canaries and Madeira along the north- east tradewinds route.’

A return voyage from the Caribbean to northern latitudes can be testing for boats and crew.

Photo: Tor Johnson

The route back is a well-travelled one, but it is a very different proposition to the way out.

The days will be lengthening as a crew sails north-east, yet the temperatures are falling and the weather can be very varied and occasionally testing.

Dan Bower, who wrote our

Bluewater Sailing Series and made his umpteenth west-east transatlantic passage in May 2018, returning from the Caribbean on his Skye 51 Skyelark, says: “We consider the passage to be heavy weather and prepare accordingly.”

But it is also one of the most interesting voyages, and the almost mandatory stop in the Azores means you’ll visit some of the most unspoilt, hospitable and interesting islands anywhere in the world.

Plus there is the undoubted satisfaction of knowing that you are closing the circle of your Atlantic circuit by your own efforts and skills.

Preparations

“We look at the west-east transatlantic as very different from the ARC or indeed any of the other ocean trips we do because it can be largely upwind and has potential for heavy weather,” says Dan Bower.

“It is guaranteed that the first week is full on, close-hauled in the tradewinds, and life at 20-30° in a big ocean swell puts more demands on the boat and crew. Then depending on the position of the Azores High, after the lull in the middle, the second half of the journey can be lively downwind or back to beating.”

Make regular checks on sails and rigging, looking particularly for chafe damage.

Photo: Tor Johnson

Given this, you’ll need to think from the outset about your upwind and stronger wind sails, and your yacht preparations for the route across to Europe.

So when you consider the outlay for an expensive downwind sail inventory, for example new spinnaker or Parasailor, don’t forget the good condition mainsail with perhaps a fourth reef and the strong staysail that will be just as invaluable on the way back.

Preparing your boat for everything from flat calms to gales is paramount, and after a lazy season in the Caribbean everything needs to be checked over.

Skip Novak’s Storm Sailing Series features a run through some of the essential deck checks.

Dan Bower also emphasises these basic checks.

“A good inspection and rig check before departure is a must, and we rig for heavy weather with our smaller headsail on the furler and have the staysail ready to go.

“We also consider taking some extra fuel on board to give options around the high.

Because of the water that will be shipped going into a big swell, all items on deck need to be well lashed down, and thought given to any water entry points.

We seal our chain hawse pipe and block off dorade vents.

Thought also needs to be given to what items you will need to be easily accessible first, so that you’re not trying to fight to the back of a windward locker as you’re landing off a wave, or needing to access the forepeak for a spare rope.”

Careful and comprehensive rig checks are essential for an Atlantic crossing in either direction.

Photo: Richard Langdon

Fuel and spares

As well as taking extra fuel in jerrycans or flexible tanks, don’t forget to pre-empt fuel supply problems by stocking lots of engine fuel filters and lots of Racor water separator filters.

On most crossings you rarely use the engine, but if it’s a light wind year its great to have the ability to push through a wind hole and get into the wind on the other side, more fuel gives you more options.

Also, consider buying a portable transfer pump as juggling with funnels and pouring diesel at sea is a messy, troublesome job.

To get the most from your fuel tankage, keep to your minimum cruising revs.

Boat manufacturers should be able to give you a fuel consumption curve for your engine so you can calculate your range based on engine hours and how much fuel is in your tank.

Duncan Sweet runs Mid-Atlantic Yacht Services in Horta, providing a great service, but one that gets very busy in late April and May.

He advises skippers to be prepared to do oil and filter changes themselves.

“I get people coming in here to ask us to do it and I have to say: ‘No, sorry, we don’t have time’,” he says.

Sweet also strongly advises that you carry key spares you might need, and replace any you may have used after your Atlantic crossing on the way out, such as pump or autopilot parts.

Getting spares out to the Azores can be difficult and takes time.

Carry spare fuel in case you have to motor more than you expect, and find out from your boat manufacturer your vessel’s most economical engine cruising revs

“The average time people spend here is four to five days.

If you have to wait for spares that will be six to ten days, depending on the supplier at the other end, it will delay you, and the cost of transport [air freight], for, say, a pump can be €60-80 per leg for the two legs.”

A good rigging check before leaving is essential.

Your standing and running rig will now have covered thousands of salty, sunny miles and the return transatlantic crossing will see you spend long days on one tack so expect chafe to occur on sheets and halyards.

A professional rigging check can be well worth the cost, but if you do it yourself make sure you work from stem to stern checking every item.

Jerry Henwood, aka Jerry the Rigger, who does most of the rig checks for the ARC rally advises: “Check your standing rigging wire where it enters the swage. Is it nice and smooth? The most common place for standing rigging to break is just inside the swage and as it’s inside you can’t always see it, but you can feel it.

“Look at the mast, boom and spreaders. Check all areas where anything joins, exits or is just attached.

It should all be smooth with no cracks. All fastenings must be tight and secure. And check all split pins and key rings and make sure these are taped up so that anything passing over them (ropes, clothing, sails, etc.) does not catch on them and pull them open.”

Here’s more from Jerry’s hit list:

- Check for any missing or damaged key rings on standing rigging, especially guardwires.

- Check for any loose nuts on pelican hooks on the guardwires.

- Check there are no cracks on the tang on the boom where the vang joins.

- Check struts on the radar brackets aren’t wearing away or coming loose.

- Check VHF aerials at the masthead aren’t loose.

- Re-mouse all your shackles so they don’t come undone.

Choosing the best route

Should you sail to the Azores (generally Horta) or go the longer route via Bermuda?

There are pros and cons to each.

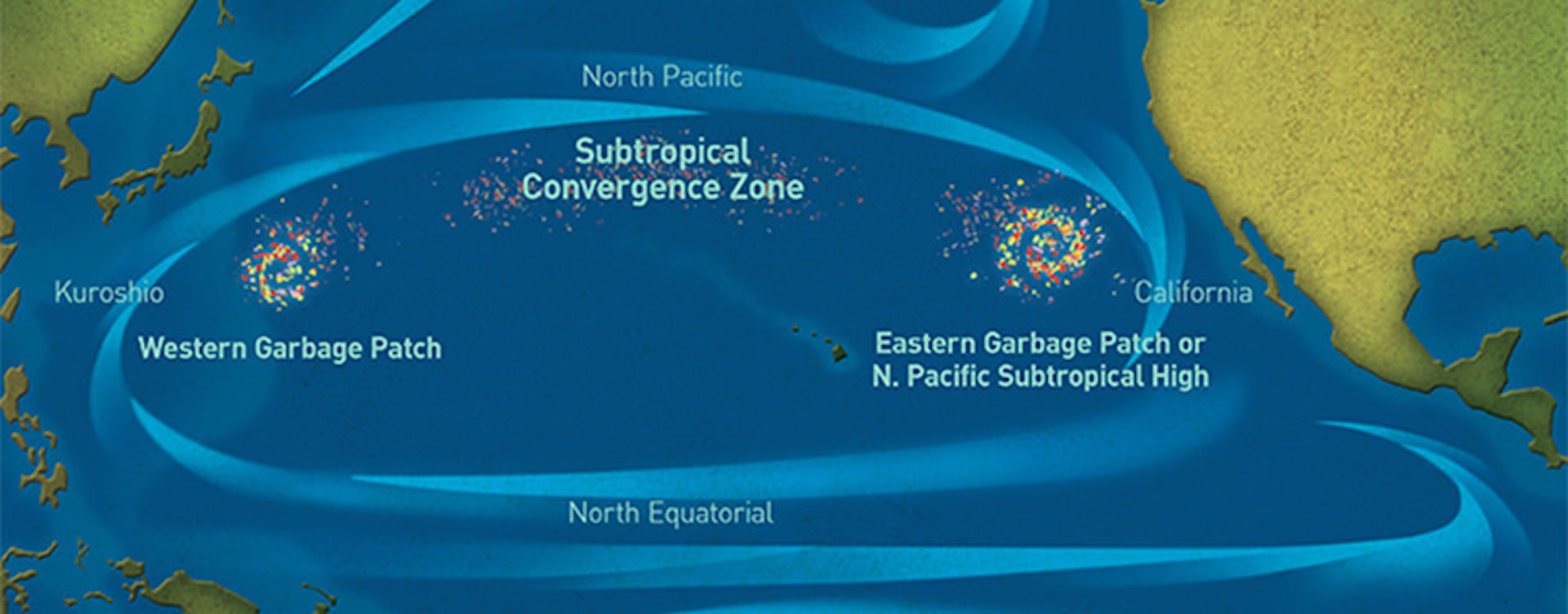

Weather systems spinning off the US East Coast bring lows and frontal systems that can extend well south, and at some point a yacht making the west-to-east crossing will be overtaken by at least one front, possibly more.

So the aim is to catch and ride favourable winds for as far as possible, and most boats head for the Azores to make a stop there and then pick their timing to head across to Spain or Portugal or up to the UK.

Photo: Isbjorn Sailing

Tortola in the British Virgin Islands or St Maarten are the most popular starting points – they are well positioned and good for provisioning, spares, chandlery and repairs.

But many crews make an intermediate stop in Bermuda and this is a particularly good option if the wind patterns change three to four days out from the Caribbean.

In Bermuda, crews can take a break, re-provision, enjoy the island, and wait for a good weather springboard for the next leg.

According to Jimmy Cornell, author of World Cruising Routes, as early as March and as late as mid-May there are reasonable chances of favourable south-easterly and south-westerly winds on leaving the Eastern Caribbean.

The advice he offers is to track north-easterly towards the Azores and stay south of 30°N until 40°W.

For decades, the late Herb Hilgenberg provided free weather services to eastbound yachtsmen, and when I interviewed him a few years ago he also advised an even more cautious route:

“I advocate the southerly route to the Azores,” he said, “and recommend that boats head east and stay south of 35°N until I see that nothing significant is developing.

“You can stay at 32-33°N until a few days out from the Azores and then head north.

I would not go north of the area north of 35°N or west of 45°W until June.”

Low pressure systems tend to lie further south earlier in the season and if you head north you would typically end up north of the Azores in headwinds.

As summer approaches the lows tend to move further north and the Azores High expands so that you get lighter winds as you make your way towards the Azores.

For cruisers a southerly route is generally preferable, staying south of the Gulf Stream in lighter winds and taking on extra fuel and motoring if necessary.

Photo: Tor Johnson

Weather forecasts

Whether or not you’ve considered paying for tailored forecasting and routeing information on the way out to the Caribbean, it’s a good investment on the way back.

In effect, you’re gaining an extra crewmember, someone with proper connectivity to put the hours into obtaining weather data including real time information from satellites and weather buoys, to work out your best options.

Weather experts can provide a service as and when you need it – what forecaster Simon Rowell calls ‘leaving note for the milkman’ – or on a daily basis.

A good forecaster will ask you to check in anyway and will be keeping an eye out for anything untoward heading your way.

They will help you decide how to shape your route, and even adapt your sailing to, say, slow down if necessary and track south out of stronger winds.

Rowell estimates his costs for providing this service to an average 40-footer doing Atlantic crossing at around £500, while Stephanie Ball at MeteoGib charges around £70 for daily 24hr SMS-type forecasts to a satphone or tracker.

You can sign up to more comprehensive information and grib files, or request forecasts every two or three days.

Some reputable forecasters include:

Hearty, warming meals will be required as the temperature drops.

Photo: Isbjorn Sailing

Crew for the voyage

You might not have quite the number of takers for a voyage to Europe as you had on the way to the Caribbean and, as skipper, you need to think about crew who have the appetite for what might be more of challenge.

As Dan Bower puts it: “There is an increased chance of seasickness and even for those not afflicted there is less desire to do much in the way of domestic duties.

“Crew agility and fitness becomes more important as deck work and moving around the boat can be a challenge, at least initially.”

On Skyelark, they make life easier by pre-cooking most of the main meals and keeping lunches and breakfasts simple, though “we carry some other celebration meals for when conditions merit; a Sunday roast is great for morale,” he says.

Photo: Tor Johnson

Hearty and warming meals are needed just at a time when you will be sailing at an angle for perhaps days, so anything that makes it easier is worth investing in.

A pressure cooker will come back into its own for probably the first time since you left colder waters.

Round the world sailors Anne and Stuart Letton, who have sailed two-handed back across the Atlantic several times, recommend Mr D’s Thermal Cooker, a slow cooker you can put all the ingredients in during the morning, bring to a simmer and then leave to cook slowly throughout the day to be ready in the evening.

You also need to unpack all those mid-layers and boots that got stowed away when you reached the Tropics.

By day the temperatures might be warm enough for T-shirts and shorts, but at night it can get quite cold.

This also makes watchkeeping more tiring, so you may want to consider changing your previous rota.

Rolling watches or double watches can help the time go by quicker, and give you as skipper more confidence and rest, though it might mean you need more crew for this route.

The weather will be cooling on a west-east Atlantic crossing… but there might still be a chance for a mid-ocean swim.

Photo: Tor Johnson

But the way across to Europe is one of the best ocean voyages, argues Dan Bower.

“With all of the above in mind, this remains one of my favourite trips.

You have powerful upwind sailing, the days are getting longer, the weather and skies becoming more interesting and the sea and bird life are plentiful.

“The lighter winds midway give a chance for the boat and crew to be scrubbed clean, and perhaps you get a chance to have a mid-ocean swim and a midway celebration, before (hopefully) a downwind ride to the Azores, where the sense of accomplishment and the warm welcome is remembered by every sailor who ever visits.”

Links :