Teens, from left, Cyrus Chambers, Rondell Franklin and Jayden Hill

joined a sailing camp this summer in Annapolis, whose waterfront has

become harder to access than ever.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

From WP by JoAnna Daemmrich![]()

Barefoot and in borrowed life jackets, Jayden Hill and Rondell Franklin leaned back in their 12-foot dinghy, skimming alongside the sleek yachts and sightseeing boats of the Chesapeake Bay.

Neither had sailed before this summer, nor been so close to

the Naval Academy’s rocky sea wall, the fenced-in luxury homes or the secluded private beaches of their unequal hometown.

Yet as they let out their sails, turning back toward Annapolis, both boys looked as comfortable as if they were chilling on a couch.

“It’s an incredible feeling,” said Rondell, 14, a soon-to-be high school freshman who lives in one of Annapolis’s public housing projects.

“When you play sports, you have to do everything at a certain pace.

With sailing, you can go on your own and take your time.”

Sailing is like religion in Maryland’s capital, where children from well-to-do families learn early at exclusive yacht clubs the way kids elsewhere might learn to ski.

But while Annapolis once had stretches of shoreline where anyone could fish or set sail, the small town now teems with tourists and nautically themed bars, its waterfront areas Whiter, wealthier and less accessible than ever.

Jayden and Rondell’s mentor, Thornell Jones, is among those seeking to turn back the tide.

Jones, 84, pulled together the money this summer to send them and two other boys to sailing camp at the Eastport Yacht Club, where Jones is one of the only Black members.

The club contributed scholarships for four more kids to attend its $450-a-week camps, which sell out months in advance.

And a nonprofit partnered for the first time with a sailing school to provide a week of training to a dozen children from Black and Latino communities.

“When you learn to sail as a kid, you learn everything about the water and the wind, and it becomes part of you,” said Jones, still spry despite his spectacles and graying mustache.

“If you don’t have access to the water, if you don’t have any connection to people on the water, it’s harder to imagine.”

Cyrus Chambers, 15, left, watches his friends Jayden Hill, 15, and Rondell Franklin, 14, sail in Annapolis. “It’s an incredible feeling,” Rondell said.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Thornell Jones, 84, who helped send teen boys to sailing camp this summer, preaches that the sport can open opportunities for scholarships and employment.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Jones could imagine it growing up.

Sailing was his boyhood dream, conceived when he was 5 years old and spotting white-sailed boats gliding past a New Jersey riverbank, a sight he still calls “magical.” But in the Jim Crow 1940s, no program would teach him.

A half-century later, Jones retired from his IBM marketing job and moved to Annapolis, determined to sail at last.

But even as he organized Friday night races and joined the U.S.

Coast Guard Auxiliary, Jones discovered that in “America’s Sailing Capital,” the sport was not much more integrated than in his youth.

He was dismayed that children growing up a few blocks from creeks dotted with elegant sailboats had never noticed them.

That’s a systemic problem, noted Deni Henson, who grew up here in the 1960s, when the town of 41,000 was low-key and working-class, home to oystermen and crabbers.

Henson recalled an “idyllic type of childhood” catching crabs and swimming along the Eastport peninsula, before soaring property values forced out most of its Black community.

Fences went up, restaurants opened, and as multimillion-dollar homes replaced cottages and working boatyards, informal access to the water gradually disappeared.

“If you’re the average African American kid here, you live on a peninsula surrounded by the water, but you can’t get to the water,” said Henson, who still owns her grandparents’ home, next to an oyster plant that’s now a museum.

“You can’t just go down to the beach like I did and swim.”

Teens rig up 12-foot sailboats to take out onto the Annapolis bay. Development has crowded out the informal spots where kids used to fish or set sail.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Over the past few summers, as pandemic-era crowds overran public piers, coves and the downtown harbor nicknamed “Ego Alley,” Annapolis officials have searched for solutions.

Earlier this month, conservationists celebrated saving a fragment of a historic Black beach for a park.

The city has launched a water-equity study and made plans for new kayak launches and an electric ferry.

But only so much can be done, since almost all of the town’s 17 miles of shoreline is privately owned.

In Eastport, tensions over water access are rising as fast as the high-end, gated-off housing, and waterside neighbors are installing bushes to block coves where some used to paddle.

“Every rich person wants to protect their access to the water,” said Diane Butler, 60, a sailor who serves on the city’s planning commission.

“They take five feet on one side, five feet on another, and there’s less left.”

A public sailing school could broaden opportunities and rival the powerful yacht clubs, which run the high school teams and charge junior membership fees.

But some Annapolis leaders question whether the city could afford one.

“The issue isn’t access to the water,” said former mayor Ellen Moyer, who worked to preserve the street-end coves, including the handful now in dispute.

“It’s the equipment, maintenance and liability.”

Kids in Annapolis typically learn to sail at exclusive yacht clubs Annapolis leaders say a public sailing school might be too costly to maintain.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Jones has tried for years to introduce more kids to sailing, especially those living in areas tourists rarely see.

He’s knocked on doors and talked to donors.

He’s taught fifth-graders contours of the Bay.

He’s preached that knowing how to sail can change lives, opening opportunities to high school teams, college recruitment, or well-paying jobs.

“Too many young people here don’t understand there’s a marine industry here desperate for workers,” he said.

Equally important, Jones hoped that by sailing for three weeks, through sunshine and wind, choppy water and the occasional rainstorm, the boys would emerge proficient enough to teach younger kids.

He envisions developing “a nucleus of young Black sailors” to transform the sport for the next generation.

Tyler Womack, 15, prepares to head onto the bay July 21.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Jones’s teens had to conquer the tedious art of untangling ropes.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

In the stifling heat of a recent morning, Jones’s four teenagers clustered with younger campers in a gravel lot, their expressions serious as they fumbled with knots.

Two instructors, competitive sailors though barely older, demonstrated how to attach a lightweight spinnaker to sail off wind.

Jayden, 15, sweating as he struggled with the kite-like sail, joked: “I was ready to cry if we were going to do this every day.”

Jones kept track of the boys’ progress as they conquered the tedious art of untangling ropes, raising sails and memorizing courses.

He dropped by with sandwiches, cold drinks and nautical charts to teach them navigation.

Though local nonprofits regularly organize tours of ships and sailing excursions on private boats, Jones didn’t want to settle for a tourist outing.

He wanted the boys to handle boats themselves.

Not many young African Americans do.

A 2020 nationwide survey of college sailors found that less than 1 percent were Black.

The National Sailing Hall of Fame, which left Annapolis in 2019 for Newport, R.I., only inducted its first Black sailor last year.

“Coming up in the sport, I didn’t see a lot of people like me,” said Preston Anderson, 22, who sailed for Bowdoin College and organized the diversity task force that orchestrated that poll.

“We’re really trying to find ways to attract new sailors, because you never know: You could have that walk-on on your team, and in four years, they could be an all-American.”

Jayden Hill, center, gets more than a sip of water from Cyrus Chambers, right, before they set sail.

A 2020 nationwide survey of college sailors found that less than 1 percent were Black.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Ky’Niya Henson, 13, might be one.

The eighth-grader, who is not related to Deni Henson, lives in a ground-floor apartment at Harbour House, a housing project that has no water views despite its name.

Though she loves to swim, she avoids her community pool, worried about broken glass on the deck.

Three years ago, a mentor introduced Ky’Niya to sailing and helped her win scholarships to the Eastport Yacht Club.

She initially felt shy among the other campers, in their Vineyard Vines swimsuits and proper boating shoes.

Now, she says, she wants to sail all her life.

“It’s just so open.

You see the water, and trees, and everything you don’t see on land,” Ky’Niya said.

“It makes me feel really free.”

Jones’s boys felt the same.

On the water, they came to savor a quiet that can be elusive in town.

“It’s peaceful,” said Rondell, who lives in Robinwood, where during the second week of camp a man and woman were shot outside their apartment.

But the boys were most exhilarated by their ability to control a boat, to chart their own direction and “go fast” on windy days.

“We didn’t know much about it,” said Jayden, recalling his apprehension during Jones’s first lessons.

But “especially now that we’re going out on the water, I just love it.”

Sailing instructor Jack Wigmore, left, goes over the racing course for the campers in July.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Near the end of their final week, the coaches arranged a mock race.

As the eight campers set out, trying to remember a complicated two-mile course, Jayden and Rondell drifted far behind.

Close to the channel marker, though, a gust of wind snapped them to attention.

With their coaches shouting directions, Jayden yanked the tiller, Rondell snapped the jib and they surged into the lead.

Their advantage would be short-lived as the wind shifted, but neither seemed to mind.

Rondell’s thoughts were turning toward his first year at St.

Mary’s High School, where he figured he would be too busy with football and basketball to join the sailing team.

Jayden was looking ahead to football tryouts at Annapolis High; he announced he might sail “after I retire.”

Jones had other plans for them.

“Triumphant” at the boys’ progress, he was already planning on signing them up for yacht club races, introducing them to paddleboard companies looking for workers, and another summer of lessons so they could become junior instructors.

The camp was three weeks, but the title, Jones had decided, was lifelong: Like him, they are sailors.

Links :

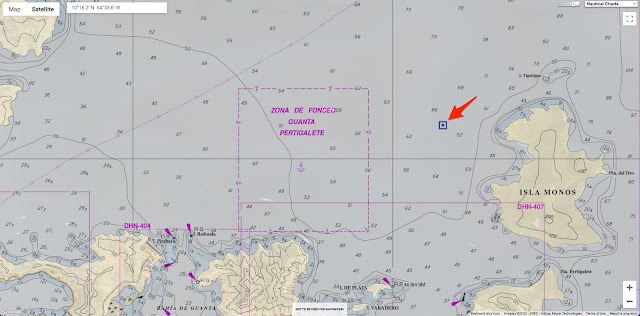

Localization with the GeoGarage platform (DHN Venezuela raster chart) : no info on rock

Localization with the GeoGarage platform (DHN Venezuela raster chart) : no info on rock