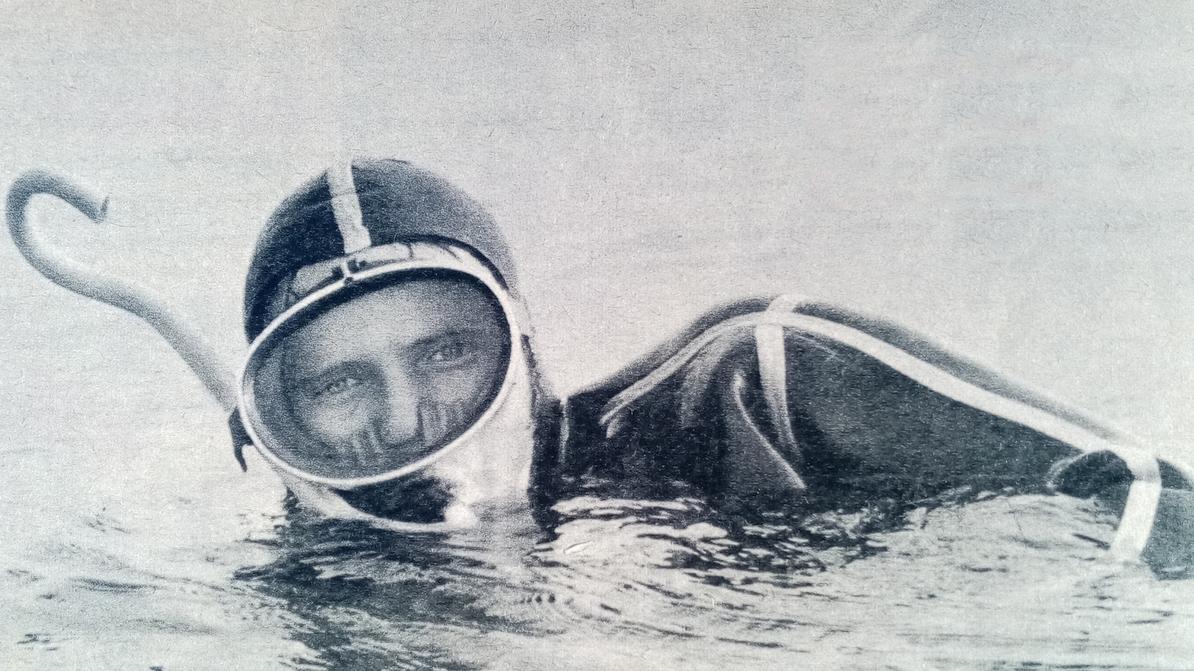

On his arrival in West Germany, Peter Döbler reconstructed his adventure for a German tabloid.

The incredible story of Peter Döbler, who swam away from the GDR

“Only the tube of my snorkel was emerging”.

From The Guardian by Philip Oltermann

Tales of Berlin Wall escapes are well known – but those daring East Germans who fled across the ‘invisible border’ into Denmark using kayaks, surfboards or home-built submarines are only now coming to light

In the north-western corner of Bispebjerg cemetery, a leafy graveyard on the outskirts of Copenhagen, lies a plot of land with a secret.

An old rumour has it that it contains the bodies of 12 East German citizens who were mysteriously washed up on Denmark’s coast in the late 1970s.

More than 5,600 East Germans tried to escape the GDR via the Baltic Sea between 1961 and 1989, aiming either for Danish soil some 40km away, or the nearer West German coastline.

Less than 1,000 made it, and scores are believed to have died.

Yet many of their stories remain untold.

Refugees on the Gedser Rev in 1968.

The Danish ship rescued dozens of East Germans in the cold war. Photograph: Niels Gärtig/Jesper Clemmensen

But the tales of those East Germans who tried to flee across the “invisible border” on the Baltic coast – on kayaks, surfboards, lilos or home-built submarines – have mostly vanished into the watery depths.

Only recently has the Baltic sea’s role during the cold war attracted new interest in Germany.

This year’s winner of the German equivalent of the Booker prize, Lutz Seiler, has dedicated an entire chapter chapter of his novel Kruso to the Bispebjerg graveyard mystery.

And the director of Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie Museum hopes to raise funds for DNA tests on the buried bodies.

The total number of victims of the Berlin Wall is widely known: 138 people died trying to cross the border in the German capital.

Exactly how many people were killed while attempting to pass from one state to the other in the whole of Germany remains far from clear, however.

The most extraordinary story ...

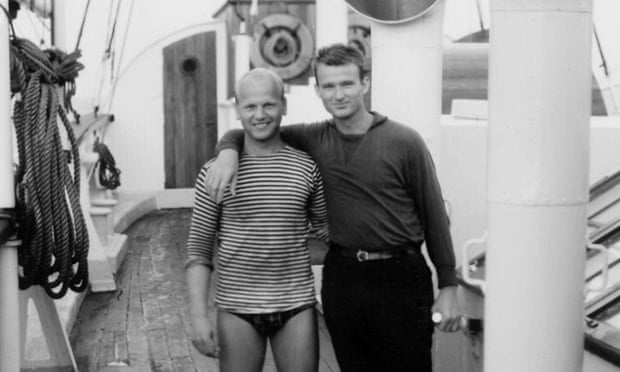

GDR escapee Manfred Burmeister with his homebuilt ‘underwater scooter’.

GDR escapee Manfred Burmeister with his homebuilt ‘underwater scooter’.

Photograph: Niels Gartig/Jesper Clemmensen

Two separate Berlin institutions are currently trying to come up with a total figure.

The director of the Museum at Checkpoint Charlie, Alexandra Hildebrandt, keeps a tally started by her late husband Rainer, the museum’s founder, which currently lists 1,720 victims.

A team of academics at Berlin’s Technical University lead by historian Klaus Schröder has since 2012 been trying to come up with a more academically credible total, by comparing records from the east and western side of the Wall, many of which were until recently blocked because of ongoing trials against border staff.

Their project, too, yields a much higher number than previously assumed: out of around five million people who tried to cross the border between 1949 and 1989, it says 1,128 lost their lives in the process.

The vast majority of border victims were male manual labourers under the age of 25, Schröder explains in his office in Berlin Dahlem, “which is ironic given that the GDR styled itself as a workers’ state”.

While many intellectuals or doctors could find ways of leaving the countries by official means, workers who had fallen out with the regime often had no other means of escape than a desperate dash across the border.

Yet even this latest research is unlikely to clear up the Bispebjerg graveyard mystery: researching the human cost of the Baltic border, Schröder said, would have exploded his team’s budget.

On a map, the stretch of water that separated the East German coastline from the West looks deceptively narrow.

The distance between the southernmost tip of Denmark and the coast near Rostock barely measures 40km.

Yet the little patch of sea between East and West Germany by Travemünde was fiercely guarded by watchtowers with radar systems, coastal patrol boats and keen informants in the fishing industry.

According to the Stasi archive’s research centre at Rostock, more than two thirds of escapees, around 4,500, were captured and sent straight back to prison.

Many of those who tried to evade the patrol boats by taking a less direct route were caught out by the elements.

Low salt levels make the water in the Baltic sea light and prone to high waves during bad weather.

The lowest figure for those who drowned at sea is 174.

The around 900 East Germans who managed to successfully escape across the Baltic sea did so thanks to either extraordinary determination or moments of rare ingenuity.

In July 1971, Peter Döbler swam for 24 hours without break to cover the 48km between Kühlungsborn in the GDR and Fehmarn island in West Germany, using weight-loss tablets and chocolate bars as energy boosters.

In November 1986, East Berliners Karsten Klünder and Dirk Deckert entered the waters off Hiddensee on surfing boats with handmade sails.

Separated in the rough sea off the island, Klünder managed to make his way to the Danish island of Møn, while his friend Deckert was rescued by a Danish fishing boat more than 24 hours after leaving East Germany.

Many of the stories of failed and successful escapes have only surfaced in recent years, thanks to the investigative work of Danish journalist Jesper Clemmensen, who interviewed a large number of German refugees and their Danish helpers for his 2012 book Escape Route: Baltic Sea.

One his key sources is Niels Gärtig, a former captain of the Gedser Rev, a lightship stationed about 17km from the East German coast, which served as a de facto extension of the Danish border.

Between 1962 and 1972, Gärtig managed to pull at least 50 East Germans out of the Baltic sea.

“August to October were always the busiest periods for us: the water would still be warm, but the nights would be still be long,” he said.

Once on board, the refugees would be given dry clothes and kept under deck, to hide them from the patrol boats and helicopters that liked to inspect the Gedser Rev up close.

Then Gärtig would radio the local post boat to bring his stowaway to safety, using a pre-agreed codeword in case the Stasi was intercepting his call: “We’ve run out of water.”

Low salt levels make the water in the Baltic sea light and prone to high waves during bad weather.

The lowest figure for those who drowned at sea is 174.

The around 900 East Germans who managed to successfully escape across the Baltic sea did so thanks to either extraordinary determination or moments of rare ingenuity.

In July 1971, Peter Döbler swam for 24 hours without break to cover the 48km between Kühlungsborn in the GDR and Fehmarn island in West Germany, using weight-loss tablets and chocolate bars as energy boosters.

In November 1986, East Berliners Karsten Klünder and Dirk Deckert entered the waters off Hiddensee on surfing boats with handmade sails.

Separated in the rough sea off the island, Klünder managed to make his way to the Danish island of Møn, while his friend Deckert was rescued by a Danish fishing boat more than 24 hours after leaving East Germany.

Many of the stories of failed and successful escapes have only surfaced in recent years, thanks to the investigative work of Danish journalist Jesper Clemmensen, who interviewed a large number of German refugees and their Danish helpers for his 2012 book Escape Route: Baltic Sea.

One his key sources is Niels Gärtig, a former captain of the Gedser Rev, a lightship stationed about 17km from the East German coast, which served as a de facto extension of the Danish border.

Between 1962 and 1972, Gärtig managed to pull at least 50 East Germans out of the Baltic sea.

“August to October were always the busiest periods for us: the water would still be warm, but the nights would be still be long,” he said.

Once on board, the refugees would be given dry clothes and kept under deck, to hide them from the patrol boats and helicopters that liked to inspect the Gedser Rev up close.

Then Gärtig would radio the local post boat to bring his stowaway to safety, using a pre-agreed codeword in case the Stasi was intercepting his call: “We’ve run out of water.”

Museum ship ...

Museum ship ...the plaque on the Gedser Rev in Copenhagen harbour makes no mention of its heroic role during the cold war.

Photograph: Philip Oltermann

His most extraordinary visitor, he recalled, arrived on 10 October 1969.

Engineer Manfred Burmeister had decided to leave East Germany after hearing about the violent crackdown on the Prague Spring in 1968.

But since he worked on a radar factory in Berlin, he knew leaving the GDR over the sea wasn’t as easy as some thought.

He needed to be be able to travel underwater.

Over the coming months, he combined a chimney tube and the motor of an old moped with a propeller from a car’s heating-cooling unit to create a “submarine scooter” that would be able to pull him out to sea while he was breathing through a snorkel.

After a series of test dives in Berlin’s Müggelsee lake, he packed his invention in two suitcases, travelled to the seaside resort of Wustrow and slipped into the water in the early hours of the morning.

When Burmeister reached the Gedser Rev, he made sure the device that had pulled him to freedom was lifted on to the ship before him.

Unlike West Germany, Denmark often played down its role in helping East Germans to flee the GDR.

“The Danish government seemed to be a bit worried about damaging its good trade relations with the GDR,” said Clemmensen.

As a result, the monumental rescue effort played by Danish rescuers has been nearly lost to history.

Decommissioned in 1972, the Gedser Rev now lies in Copenhagen’s Nyhavn harbour as a museum ship.

A plaque on its side tells some of the ship’s adventures, but makes no mentions of its heroic role during the cold war.

Lost to history ...

German graves in Bispebjerg cemetery, where it is said GDR refugees may be buried.

German graves in Bispebjerg cemetery, where it is said GDR refugees may be buried.

Photograph: Philip Oltermann

A visit to Bispebjerg cemetery, a mere 6km up the road, also reveals no further clues.

The north-western corner of the graveyard, so large that it can be accessed by car, may have a section with German war graves, and a plaque that references “594 refugees”, but there is no indication that they were buried any later than 1944.

The main source behind the legend is Erik Jensen, a former harbour master at Klintholm.

In 1992, he told a German journalist that fishermen between Møn and Rügen used to frequently catch the bodies of East German refugees in their nets: “I can remember 12 of them.” Yet Jensen now suffers from dementia and is unavailable for interview.

Bispebjerg’s grave supervisor, Stine Helweg, said she could find no reference to GDR refugees in her records.

Copenhagen police stated it was far more likely that the bodies had been buried in local graveyards on the coast.

Some of the stories may be forever lost in the fog over the Baltic sea.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment