photo : World Wide Wind

A Norwegian startup claims that its strange wind turbine design will be able to produce more than double the electricity of the largest unit on the planet.

But first they have to test it.

The type of wind turbine you’re used to seeing in stock photos of wind farms is called a horizontal axis wind turbine (or, HAWT).

But there is another form of wind power, called a vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT), in which the blades rotate on an axis perpendicular to Earth’s surface.

This type of turbine can work better in unstable wind conditions because they don’t need to be pointed into the wind, but still produce much less electricity and durability problems because of the force the wind exerts on them.

That’s why you would only see VAWTs in small applications, like homes, and HAWTs in wind power farms.

But a new company claims to have improved on the VAWT design.

The invention could create a turbine with a maximum output of 40 megawatts, far surpassing the 15 megawatts of the world’s current largest turbine.

That company is called World Wide Wind, a Norwegian startup.

The Norwegians—rich, thanks to their oil and gas reserves—want to dramatically increase their wind energy production to 30.000 megawatts by 2040.

Their industry’s interest in offshore wind energy is so big that there is a waiting list to test new technologies off its coast, which is on the incredibly windy shores of the North Sea.

In June 2021, company founder Stian Valentin Knutsen wondered if it would be possible to have two sets of rotor blades on a single turbine mast, making them rotate in opposite directions.

“The idea was to increase the energy output of the vertical turbines while simultaneously eliminating the increased torsional forces and the inherent problems associated with upscaling traditional HAWTs for increased energy outputs,” company spokesperson Elsbeth Tronstad told me via email.

Knutsen looked for scientists to test the possibilities and finally met Hans Bernhoff, a professor at the department of electrical engineering at Uppsala University, in Sweden.

According to the company, Bernhoff had been doing research on vertical wind turbines for more than 20 years, building his own 200 kilowatt (kW), 131-foot-high vertical turbine that was functional for a decade.

He was intrigued by Knutsen’s theoretical model and joined the company, developing the idea of the large tilted offshore floating turbine that World Wide Wind is now working on.

How it works

The concept of vertical axis turbines is not new, but the architecture of this machine—which the company says is patent pending—is radically different.

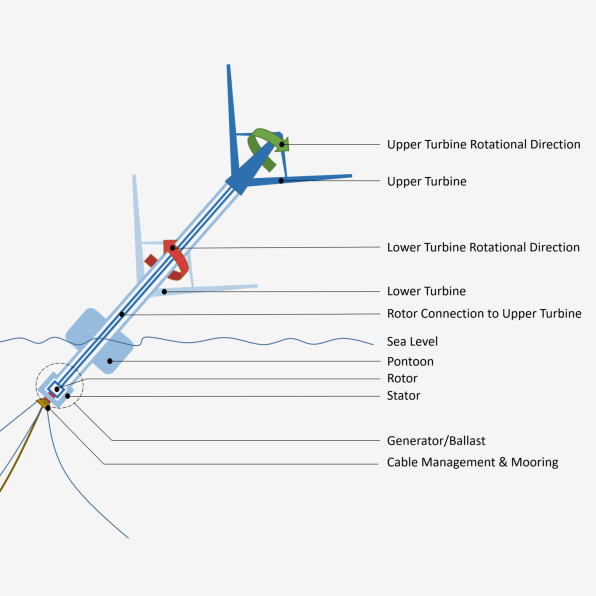

The design employs two coaxial, or counter-rotating, rotors mounted on a vertical shaft.

Each rotor has three blades that sweep in an inverted conical area thanks to its V-shape (which remind me of the arms of a mechanical tree).

The upper turbine is connected to an inner shaft that serves as the rotor in the electric generator.

The lower turbine acts as the stator, the part of the generator that contains the coils and remains static in most generators.

In this case, however, the stator moves on the opposite side of the rotor.

The result: It doubles the relative speed of the shafts and thus the electrical generating capacity of the system.

Their engineers point out that the generator is not at the top of the mast, like that of a conventional HAWT system.

but at the base, next to the ballast and all the other electrical system components, including the cables that connect it to shore.

The added weight contributes to the stability of the system, ensuring that the tower does not capsize no matter how much the ocean heaves.

This design, they say, also makes it more resistant to the vibration that greatly affects the integrity of HAWT systems, especially under very strong wind conditions.

While an underwater generator sounds like a nightmare to maintain, Tronstad tells me this is no problem: “Its interior space is all dry and there is ample space for technicians to work inside.”

The concept of vertical axis turbines is not new, but the architecture of this machine—which the company says is patent pending—is radically different.

The design employs two coaxial, or counter-rotating, rotors mounted on a vertical shaft.

Each rotor has three blades that sweep in an inverted conical area thanks to its V-shape (which remind me of the arms of a mechanical tree).

The upper turbine is connected to an inner shaft that serves as the rotor in the electric generator.

The lower turbine acts as the stator, the part of the generator that contains the coils and remains static in most generators.

In this case, however, the stator moves on the opposite side of the rotor.

The result: It doubles the relative speed of the shafts and thus the electrical generating capacity of the system.

Their engineers point out that the generator is not at the top of the mast, like that of a conventional HAWT system.

but at the base, next to the ballast and all the other electrical system components, including the cables that connect it to shore.

The added weight contributes to the stability of the system, ensuring that the tower does not capsize no matter how much the ocean heaves.

This design, they say, also makes it more resistant to the vibration that greatly affects the integrity of HAWT systems, especially under very strong wind conditions.

While an underwater generator sounds like a nightmare to maintain, Tronstad tells me this is no problem: “Its interior space is all dry and there is ample space for technicians to work inside.”

She also says that the generator design is a direct-driven permanent-magnet synchronous generator, “which requires minimal, if any, service during operation,” thanks to its lack of gearbox and other wearable parts.

[Photo: World Wide Wind]

Too good to be true ?

Logically, the mast itself does not stand upright as in conventional towers.

In fact, the mobility of the assembly to be able to operate at almost any angle is fundamental to its operation.

“Bernhoff—who is also a proficient sailor—always wanted to design an offshore turbine that would work with the wind and not against it, like current offshore HAWT units do,” Tronstad says.

The company claims that this machine automatically orients itself as the wind blows and absorbs its energy from any conceivable angle, always guaranteeing the highest possible performance.

Knutsen and Bernhoff also maintain that the counter-rotating rotors greatly decrease the turbulence typical of horizontal turbines.

But, while Tronstad says that “the first turbine drive counter-rotating generator have been already tested” and they have simulated the large-scale generator design simulated with electromagnetic with full physics, plus hydrodynamic simulations of structure and wave interaction,” and other tests are currently underway, the company hasn’t built its first full-scale prototype yet to physically validate any of these simulations.

If their simulations and theories are true, however, it could result in some crazy machines.

According to its inventors, this design can reach up to 1,312 feet in height to achieve up to 40 megawatts.

The largest turbine on the planet right now is China’s 793-foot-tall MySE 16.0-242 china, which generates up to 16 megawatts using monstrous 387-foot blades.

But if World Wide Wind’s design works, we wouldn’t need to build at such a gargantuan scale in order to get more power per square mile than we currently achieve in an offshore wind farm.

HAWT units require very large distances between them to avoid causing turbulence to each other; but World Wide Wind claims that its machines can be deployed in a higher density, thanks to the vertical design, thus increasing electric generation using much less space.

These are all bold claims.

The company is confident it will achieve these objectives based on the current testing, and Knutsen seems to have some key support from Norwegian Energy Partners, an organization dedicated to the internationalization of the Norwegian energy companies.

Still, as with any new bold innovation, it has to work in reality, not just in models; but any radical new idea that could have significant impact on the wind-energy industry and our planet is one worth developing and testing.

And we might see, before too long, how the company can fulfill its promises: World Wide Wind says it will launch its first 3-megawatt model in 2026 and a 40-megawatt model in 2029.

No comments:

Post a Comment