From SuperYachtNews by Jack Hogan

Where to next for the most capable private deep-sea exploration vessel on earth, and its intrepid owner…

The last time we spoke with Victor Vescovo, Commander, USN (Ret.), he, the team at Caladan Oceanic and EYOS Expedtions, onboard the private expedition vessel Pressure Drop, had just successfully taken scientists on the first manned descent of the Atacama Trench off the northwest coast of Chile.

Part of an ongoing series of dives to uncharted ocean depths, the Ring of Fire expedition now continues its way around the Pacific.

I met with Mr Vescovo at a café in London, shortly before he was due to receive the Don Walsh award for marine oceanic research and exploration.

It was fitting that it was Don Walsh himself, one of two crew on the first descent to the Mariana trench in 1960, along with Jacques Picard, to hand over the award that bears his name.

In what remains a mind-blowing feat of pioneering engineering, calculated risk, and an innate desire to explore, Walsh and Picard laid down a marker as to what was possible 60 years ago.

Mr Vescovo, his team, and a growing fleet of private scientific explorers now continue in this spirit.

In my last conversation, I left Mr Vescovo onboard Pressure Drop, expecting that soon he would be diving a new trench off the coast of Mexico.

His explanations as to why they did not, underline the frustration that must go hand in hand with the thrill of exploration.

“We were supposed to go and execute a dive in the MesoAmerican Trench, with a local Mexican scientist. And we never got a permit. They never denied it. But they just never awarded it, either. And I'm still not clear why we didn't get a permit. Maybe there was something happening between the scientific team and the government - we just don't know, “ says Mr Vescovo.

Part of an ongoing series of dives to uncharted ocean depths, the Ring of Fire expedition now continues its way around the Pacific.

I met with Mr Vescovo at a café in London, shortly before he was due to receive the Don Walsh award for marine oceanic research and exploration.

It was fitting that it was Don Walsh himself, one of two crew on the first descent to the Mariana trench in 1960, along with Jacques Picard, to hand over the award that bears his name.

In what remains a mind-blowing feat of pioneering engineering, calculated risk, and an innate desire to explore, Walsh and Picard laid down a marker as to what was possible 60 years ago.

Mr Vescovo, his team, and a growing fleet of private scientific explorers now continue in this spirit.

In my last conversation, I left Mr Vescovo onboard Pressure Drop, expecting that soon he would be diving a new trench off the coast of Mexico.

His explanations as to why they did not, underline the frustration that must go hand in hand with the thrill of exploration.

“We were supposed to go and execute a dive in the MesoAmerican Trench, with a local Mexican scientist. And we never got a permit. They never denied it. But they just never awarded it, either. And I'm still not clear why we didn't get a permit. Maybe there was something happening between the scientific team and the government - we just don't know, “ says Mr Vescovo.

The first person to the bottom of the Mariana Trench - Don Walsh (left), greets Victor Vescovo (Right).

Image Reeve Jolliffe

A fully crewed and operational private vessel, or superyacht, operates on an entirely different timescale to the ebbs and flows of the bureaucratic system.

A vessel as finely tuned as Pressure Drop cannot simply be turned off and wait dormant for the open-ended filling of paperwork and permits.

As Mr Vescovo says, paraphrasing another highly influential figure in the world of private exploration, EYOS founder & Expedition Leader Rob McCullum, “Sometimes the biggest hurdle to ocean exploration is not the science, it’s other people.”

As Mr Vescovo describes his team at Caladan Oceanic, working alongside EYOS expeditions, he claims it feels as if they are walking on eggshells at times.

There is a tightrope to walk concerning regulations, and there is very little in the way of international regulatory framework to operate within.

If someone has never been to a remote place, and the authorities and academic institutions do not have the technology that could get close, there is not much chance that there is a standard form to fill out that allows these operations to proceed.

At times, Mr Vescovo points out, it feels as if he and his team are restarting the process entirely before each trip.

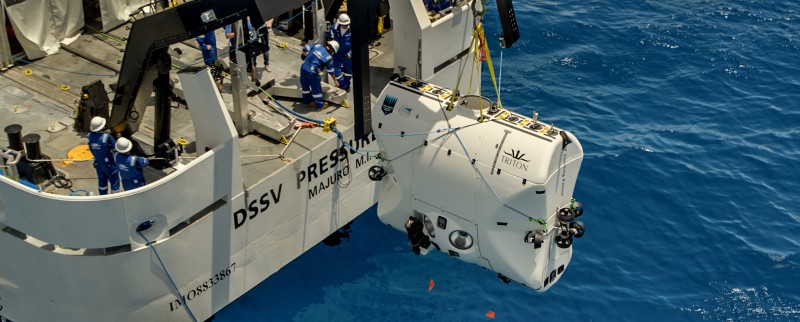

DSV Limiting Factor being lowered off DSSV Pressure Drop

DSV Limiting Factor being lowered off DSSV Pressure Drop There is no definition within the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as to what marine scientific research actually entails.

It is perhaps a testament to the rapid evolution of both the capabilities and desire of private vessels and their owners to engage with this research and push these boundaries, that these hurdles are encountered at all.

It is unlikely that those who write the legislation had anything in mind quite like a private vessel with a submersible that can operate at over 11,000m in mind.

“It's an extraordinary situation really.

If you're a private, completely philanthropic oceanographic research mission” continues Mr Vescovo, “you are subjected to a level of scrutiny that is akin to brain surgery, while a container ship can plough through and accidentally dump out four or five containers, and nothing happens.

So, the dichotomy of how the commercial world is treated and how philanthropic scientific, so-called good guy research is handled, is irrational.”

Part of the issue, Mr Vescovo explains, is that countries are now exerting a level of influence over their exclusive economic zones (EEZ) that is more akin to what is defined as territorial waters.

The 12-mile limit around most coastlines is sovereign territory, and he explains, Caladan Oceanic’s expeditions will always be very respectful of this demarcation.

EEZs, on the other hand, were established without full sovereignty in mind.

They are legally international waters.

New Zealand, for example, has the 4th largest EEZ in the world, but it does not have the fourth largest territory.

The designation of these zones is designed to protect economic, and natural resources such as fisheries, and oil and gas deposits from foreign exploitation.

Countries such as Norway have benefited hugely from their rights to the North Sea oil fields, for example.

However, the single sentence in the UNCLOS allowing countries to “regulate Marine Scientific Research” (MSR) in their EEZs has put an enormous brake on such research because now countries can – and usually do – highly restrict or even prohibit it – which is not what the drafters of UNCLOS seem to have intended.

DSV Limiting Factor returning to DSSV Pressure Drop.

DSV Limiting Factor returning to DSSV Pressure Drop.Image - Reeve Jolliffe

Mr Vescovo and his team have encountered local governments who are reinterpreting their own definitions, and they appear unsure how to interact with an expedition such as his.

As he stresses, they are there to explore, and all of the research and data collected will be made freely available.

Having the freedom to operate transparently, and in partnership with a more diverse collection of governments will allow the work that Caladan Oceanic has pioneered to expand, and, crucially, be emulated by a growing fleet of like-minded private vessels.

Superyachts for scientific exploration is, in my estimation, the most positive and impactful activity the industry can undertake.

The resources and capabilities of Caladan Oceanic, REV Ocean and OceanX have redefined what is possible, not just for intrepid individuals, but the scientific community as a whole.

While not all exploration and research-minded superyachts can undertake such extreme missions as they perform, they can conduct meaningful research and collectively the worldwide community of yacht owners can form their own scientific ecosystem, as Mr Vescovo explains:

“I actually had dinner with the head of NOAA (The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), who asked me: ‘What can we do to have a greater partnership between the public and the private sector?’ My simple answer is to publish a list of research priorities.

For example, what are the 10 research objectives that are the most challenging, but that the private sector could, with the assistance of certain governments, take on? We have a growing number of vessels and owners that are expressing interest. Is it a fun trip cruising the Amalfi Coast? No, but it is more positively impactful.”

DSV Limiting Factor awaiting pick up.

DSV Limiting Factor awaiting pick up.Image - Reeve Jolliffe

Continuing to channel the competitive nature of the owners and organisations behind exploration vessels towards impactful research will bear fruit.

One needs only to look at the reinvigoration of NASA and the space program, thanks largely to Elon Musk’s development of reuseable launch systems, for an example of what private industry can help achieve.

When we spoke about the recent successful expedition to find the Endurance, Ernest Shackleton’s ship that was lost under the Antarctic Ice Sheet a century ago, I saw the spark in Mr Vescovo, who concluded.

“Gosh, I would love to have found that ship! I am so happy for the team that did.

That is the exact kind of expedition that we would love to have done.”

Where to next then for Pressure Drop and the team at Caladan Oceanic & EYOS Expeditions? They are wasting no time heading across the Pacific for a fresh round of firsts in Micronesia.

Departing Gaum on the 12th of July, the team will head back to the Challenger Deep with Dr Dawn Wright, an American cartographer and the Chief Scientist at multi-billion dollar geospatial intelligence firm, ESRI.

This will be followed by a trip to the bottom of the Yap Trench with master Micronesian Navigator Sesario Sewralur and finally a dive at the Palau Trench with former president of Palau, Tommy Remengesau.

Then, fittingly for someone who has achieved so much on the blue planet, Mr Vescovo will be part of Blue Origin’s next New Shepard Mission NS-21, which will fly six customer astronauts into space on just the 5th human flight from the Blue Origin program.

Rob McCallum, founder of EYOS expeditions.

Regarding that flight and potential criticism that they are simply “rides” for the wealthy into space where very few people will ever get to go, Victor stressed that “Customers paying to go up in these new, 99% reusable rockets – as the New Shepard is - is actually a great thing.”

He explained, “Anything that allows us to build experience launching and recovering them increases their reliability, safety, and drives down the cost to access space for everyone over time – just like the early days of powered flight.”

Back at sea, Mr Vescovo and the team at Caladan Oceanic are far from alone in the field of private scientific exploration.

The aforementioned REV Ocean and OceanX, along with Caladan Oceanic are part of a growing group of scientifically centred private exploration organizations.

Colloquially known as the Pink Flamingo Society, they are working in conjunction with 14 international scientific organisations to coordinate the use of private vessels for research free of charge.

Concurrently, organisations such as Yachts For Science and the Seakeepers Society are working to connect eager yachts that may not be scientific specialists with suitable programs of research that can work in tandem with their operational schedules.

The combined potential to affect positive change for the ocean that this expanding network of philanthropic vessels and organisations presents is hard to overstate.

Some of the issues that Mr Vescovo has encountered will undoubtedly cause headaches again, but the next generation of collective action that these vessels and associated organisations undertake may see some of the barriers fall away as awareness increases, and our understanding of the ocean and our obligation to protect it, deepens.

Back at sea, Mr Vescovo and the team at Caladan Oceanic are far from alone in the field of private scientific exploration.

The aforementioned REV Ocean and OceanX, along with Caladan Oceanic are part of a growing group of scientifically centred private exploration organizations.

Colloquially known as the Pink Flamingo Society, they are working in conjunction with 14 international scientific organisations to coordinate the use of private vessels for research free of charge.

Concurrently, organisations such as Yachts For Science and the Seakeepers Society are working to connect eager yachts that may not be scientific specialists with suitable programs of research that can work in tandem with their operational schedules.

The combined potential to affect positive change for the ocean that this expanding network of philanthropic vessels and organisations presents is hard to overstate.

Some of the issues that Mr Vescovo has encountered will undoubtedly cause headaches again, but the next generation of collective action that these vessels and associated organisations undertake may see some of the barriers fall away as awareness increases, and our understanding of the ocean and our obligation to protect it, deepens.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog :Inside the daring mission to reach the bottom of all Earth's ... / Stories of an extraordinary world : the last of the ... / Mariana Trench: Deepest-ever sub dive finds plastic bag / Oceans' extreme depths measured in precise detail / USS Johnston: Sub dives to deepest-known shipwreck / Wall Street trader reaches bottom of Atlantic in bid to conquer ... / An explorer took a $48 million submarine on 3 record ... / Victor Vescovo: Adventurer reaches deepest ocean locations

No comments:

Post a Comment