From WP By Matthew Cappucci

La Niña is back. Here’s what that means.

The atmospheric and oceanic pattern will have a bearing on the Western drought, the end of hurricane season and the forecast for winter and spring

After a months-long period of relative atmospheric balance between El Niño and La Niña, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced Thursday that La Niña has returned.

The atmospheric and oceanic pattern will have a bearing on the Western drought, the end of hurricane season and the forecast for winter and spring

After a months-long period of relative atmospheric balance between El Niño and La Niña, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced Thursday that La Niña has returned.

It’s expected to stick around in some capacity through the winter and relax toward spring.

The intensifying La Niña should peak in magnitude, or strength, by the end of 2021, having bearings on the drought in the West, the end of hurricane season and the upcoming winter.

The intensifying La Niña should peak in magnitude, or strength, by the end of 2021, having bearings on the drought in the West, the end of hurricane season and the upcoming winter.

La Niña also plays a role in shaping how tornado season pans out in the spring.

It’s one of many drivers in our atmosphere, but it is often among the most important given the extent to which it shuffles other atmospheric features key in determining how weather evolves over the Lower 48.

In brief, here are some of the key impacts La Niña could have in the coming months:

Extending favorable conditions for Atlantic hurricane activity this fall.

Worsening drought conditions in the Southwest through the winter and potentially elevating the fire risk through the fall.

Raising the odds of a cold, stormy winter across the northern tier of the United States and a mild, dry winter across the South.

Increasing tornado activity in the Plains and South during the spring.

La Niña is the opposite of El Niño, which often makes headlines for spurring powerful southern storms that can generate beneficial rains in California and track across the entire nation.

During La Niña, such winter storms tend to be less frequent.

About six weeks remain until the start of meteorological winter (Dec. 1), and forecasters are already looking ahead to what may be in store.

About six weeks remain until the start of meteorological winter (Dec. 1), and forecasters are already looking ahead to what may be in store.

There’s still a long way to go before the first flakes fly in most places, but some meteorologists are already tossing their hats in the ring, trying to broadly gauge what lurks ahead.

A schematic for a traditional La Niña. (Climate.gov)

What is La Niña?

La Niña begins with a cooling of waters in the eastern tropical Pacific.

The basin alternates between El Niño and La Niña every two to seven years on average.

That pocket of cooler ocean water chills the air above it, inducing a broad sinking motion.

It’s that subsidence, or downwelling of cool air, that topples the first atmospheric domino.

During La Niña winters, high pressure near the Aleutian chain shoves the polar jet stream north over Alaska, maintaining an active storm track there.

During La Niña winters, high pressure near the Aleutian chain shoves the polar jet stream north over Alaska, maintaining an active storm track there.

The Last Frontier often ends up cooler than average.

The confluence of the polar and Pacific jet streams, as shown in the image above, helps drag some of that cold air across the Pacific Northwest and adjacent parts of the northern Plains.

That keeps the northern United States anomalously wet, while the South is left largely warm and dry. This is bad news for California and other parts of the Southwest, which are enduring a historic drought. The persistence of warm, dry conditions would cause the drought to worsen and potentially prolong the fire season.

La Niña arrived in fall 2020 before fading away in May 2021. Neutral conditions, bridging the divide between La Niña and El Niño, prevailed through the early fall before the NOAA’s declaration of La Niña’s return Thursday.

La Niña tends to exert a slight cooling effect on global temperatures, but recent La Niña years are warmer than El Niño years were just a decade ago because of the warming influences of human-caused climate change.

That keeps the northern United States anomalously wet, while the South is left largely warm and dry. This is bad news for California and other parts of the Southwest, which are enduring a historic drought. The persistence of warm, dry conditions would cause the drought to worsen and potentially prolong the fire season.

La Niña arrived in fall 2020 before fading away in May 2021. Neutral conditions, bridging the divide between La Niña and El Niño, prevailed through the early fall before the NOAA’s declaration of La Niña’s return Thursday.

La Niña tends to exert a slight cooling effect on global temperatures, but recent La Niña years are warmer than El Niño years were just a decade ago because of the warming influences of human-caused climate change.

Even with La Niña influencing global temperatures, 2021 still has a greater than 99 percent chance to rank among the top 10 warmest years on record, according to the NOAA.

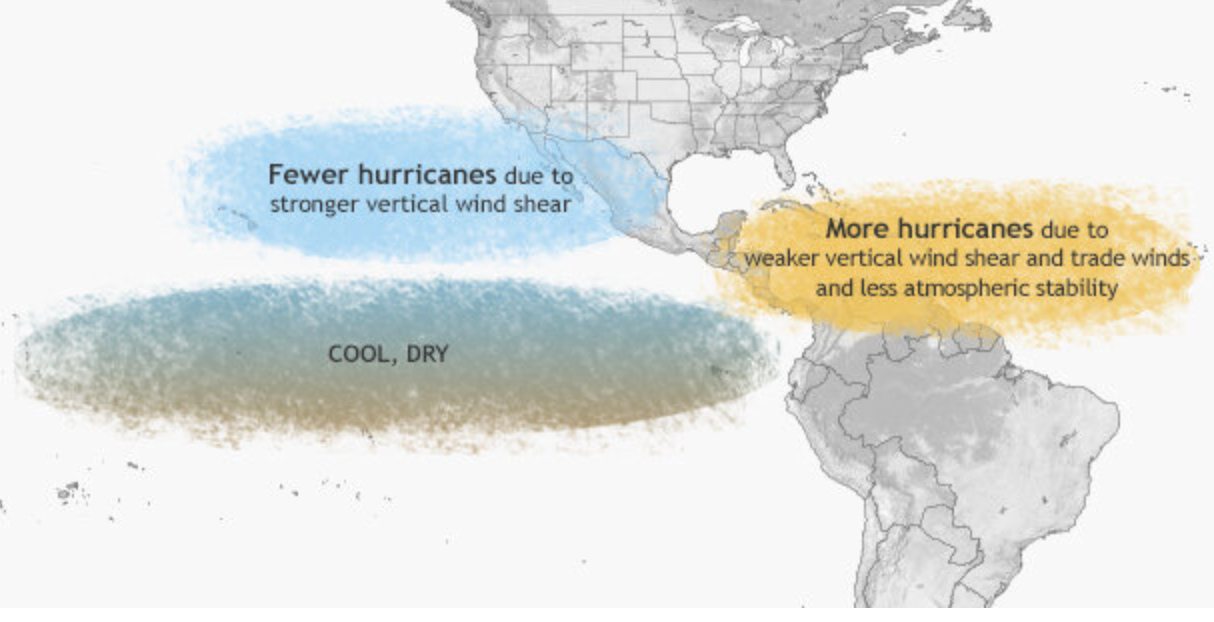

Impact on hurricane season

Conditions that have begun to skew slightly toward La Niña have already helped amplify the effects of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season, and were in large part responsible for supercharging the record 2020 season, during which 30 named storms occurred.

Though the Atlantic is mostly quiet at the moment and there are no immediate signs of tropical development, a month and a half remain in the season.

La Niña patterns reduce wind shear, or a change of wind speed or direction with height, over the Caribbean and western parts of the Atlantic’s Main Development Region (MDR), the strip of territory between the Lesser Antilles and the coast of Africa.

La Niña patterns reduce wind shear, or a change of wind speed or direction with height, over the Caribbean and western parts of the Atlantic’s Main Development Region (MDR), the strip of territory between the Lesser Antilles and the coast of Africa.

That calming of the upper-level winds is more conducive for fledgling clusters of thunderstorms to developed into named storms.

La Niña conditions also influence the Walker circulation, or a horizontal overturning circulation in the tropics, and induce broad upward motion over the Atlantic with some subsidence, or sinking, in the Pacific.

This season is running about 54 percent ahead of average in the Atlantic, but 28 percent behind typical norms in the Pacific.

La Niña conditions also influence the Walker circulation, or a horizontal overturning circulation in the tropics, and induce broad upward motion over the Atlantic with some subsidence, or sinking, in the Pacific.

This season is running about 54 percent ahead of average in the Atlantic, but 28 percent behind typical norms in the Pacific.

Usually if air is rising somewhere and enhancing storm prospects, sinking elsewhere has the opposite effect.

Though it’s impossible to predict specific storms or periods of active tropical weather, it looks like something called a convectively coupled Kelvin wave could favor more upward motion in the Atlantic beginning around Oct. 22.

Though it’s impossible to predict specific storms or periods of active tropical weather, it looks like something called a convectively coupled Kelvin wave could favor more upward motion in the Atlantic beginning around Oct. 22.

That, assisted by the nascent La Niña conditions, would indicate a window of slightly greater odds for tropical development.

What lies in store for winter

Winters are notoriously difficult to predict because of the complexities of pinpointing storm tracks, rain-snow lines and precipitation amounts more than a few days in advance.

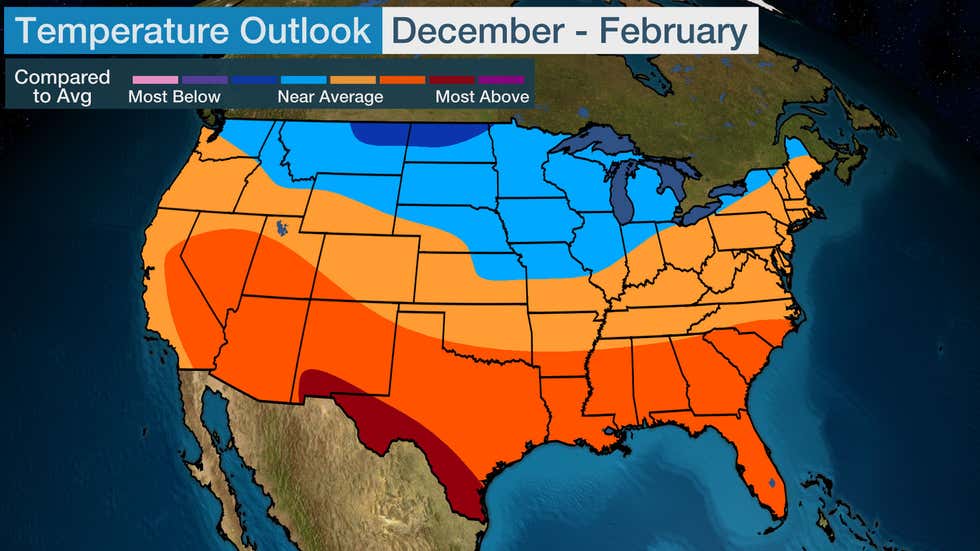

Weather.com published a broad winter outlook for temperatures that is commensurate with typical La Niña expectations, depicting below-average temperatures in the northern United States and above-average warmth in the South.

Winters are notoriously difficult to predict because of the complexities of pinpointing storm tracks, rain-snow lines and precipitation amounts more than a few days in advance.

Weather.com published a broad winter outlook for temperatures that is commensurate with typical La Niña expectations, depicting below-average temperatures in the northern United States and above-average warmth in the South.

It did not include notes on expected precipitation departures from average.

Weather.com winter temperature outlook. (Weather.com)

AccuWeather offered more details on precipitation in their outlook, predicting near to slightly above-average snowfall for New England and average snowfall in the Mid-Atlantic.

Parts of the Front Range, High Plains and Columbia River Basin in the Rockies, as well as the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys and Midwest, are included in AccuWeather’s prediction of above-average precipitation; the Southwest and Southeastern United States are in line to see unusually dry conditions.

Through the end of 2021, AccuWeather calls for little of the rain needed to ease the drought and fire risk in Southern California.

Parts of the Front Range, High Plains and Columbia River Basin in the Rockies, as well as the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys and Midwest, are included in AccuWeather’s prediction of above-average precipitation; the Southwest and Southeastern United States are in line to see unusually dry conditions.

Through the end of 2021, AccuWeather calls for little of the rain needed to ease the drought and fire risk in Southern California.

“The lack of early-season precipitation will allow the ongoing wildfire season to extend all the way into December, an unusually late end to the season,” it wrote.

The National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center isn’t slated to issue its updated December through February forecast until Oct. 16, but its mid-September outlook indicated that virtually the entirety of the Lower 48, save for the Pacific Northwest, should see near to above-average temperatures. Its precipitation forecast is similar to AccuWeather’s, with drier conditions probable in the South and an uptick in precipitation for northerly regions.

Winter forecasts depend on far more than just La Niña, though, as evidenced by the record-shattering cold blast of February that wrought havoc on Texas’s electrical grid.

The National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center isn’t slated to issue its updated December through February forecast until Oct. 16, but its mid-September outlook indicated that virtually the entirety of the Lower 48, save for the Pacific Northwest, should see near to above-average temperatures. Its precipitation forecast is similar to AccuWeather’s, with drier conditions probable in the South and an uptick in precipitation for northerly regions.

Winter forecasts depend on far more than just La Niña, though, as evidenced by the record-shattering cold blast of February that wrought havoc on Texas’s electrical grid.

Judah Cohen, an atmospheric scientist and the director of Atmospheric and Environmental Research in Boston, says it’s just too early to know how other atmospheric players may influence the season.

“The most impressive atmospheric feature [lately] has been this ridge of high pressure over Eastern Canada,” he wrote in a Twitter direct message. “It has acted like an immovable boulder in the jet stream, and if that feature stayed park over Eastern Canada for much of the winter we would all be saying ‘what winter?’ ”

He does think that could change, but a transition like that is something that weather models struggle to anticipate.

“Where that block relocates will could be potentially critical to how the winter begins and may even set the tone for the winter,” he wrote.

The behavior of the polar vortex, the zone of frigid air surrounding the Arctic, will also play a crucial role.

“The most impressive atmospheric feature [lately] has been this ridge of high pressure over Eastern Canada,” he wrote in a Twitter direct message. “It has acted like an immovable boulder in the jet stream, and if that feature stayed park over Eastern Canada for much of the winter we would all be saying ‘what winter?’ ”

He does think that could change, but a transition like that is something that weather models struggle to anticipate.

“Where that block relocates will could be potentially critical to how the winter begins and may even set the tone for the winter,” he wrote.

The behavior of the polar vortex, the zone of frigid air surrounding the Arctic, will also play a crucial role.

It’s been showing signs of weakening or becoming more unstable as of late.

A weak, unstable vortex is more prone to unleashing frigid air over the Lower 48, compared with one that is strong and stable and that tends to lock up cold over the high latitudes.

“Once the polar vortex weakens, it could be predisposed to further weakening in the coming weeks or months and we have a more severe winter,” Cohen wrote.

But Cohen also said there are influences that could halt any vortex weakening.

“Once the polar vortex weakens, it could be predisposed to further weakening in the coming weeks or months and we have a more severe winter,” Cohen wrote.

But Cohen also said there are influences that could halt any vortex weakening.

He mentioned a scenario in which “the polar vortex rapidly strengthens as we approach the beginning of winter and we have an extended mild period to begin winter and possibly persisting right through the end of winter.”

The National Weather Service’s September forecast for what may lie in store this winter. (NOAA/CPC)

Severe weather season

If La Niña lingers into spring, it could enhance the upcoming severe weather season in tornado country across the Great Plains and Deep South.

There is a demonstrable link between La Niña and a more active severe weather season.

La Niña amplifies south-to-north temperature contrasts across the central Lower 48, which sets the stage for repeated clashes of the seasons.

La Niña amplifies south-to-north temperature contrasts across the central Lower 48, which sets the stage for repeated clashes of the seasons.

That can lead to more episodes of severe weather.

The link between El Niño/La Niña and springtime severe weather. (Climate.gov)

Links :

- NOAA : Double-dip La Nina emerges

No comments:

Post a Comment