An artist’s concept shows NASA’s CloudSat spacecraft in orbit above Earth.

Launched in 2006, it provided the first global survey of cloud properties before being decommissioned in March 2024 at the end of its lifespan.

NASA/JPL

Launched in 2006, it provided the first global survey of cloud properties before being decommissioned in March 2024 at the end of its lifespan.

NASA/JPL

From NASA by Sally Younger

Over the course of nearly two decades, its powerful radar provided never-before-seen details of clouds and helped advance global weather and climate predictions.

CloudSat, a NASA mission that peered into hurricanes, tallied global snowfall rates, and achieved other weather and climate firsts, has ended its operations.

Originally proposed as a 22-month mission, the spacecraft was recently decommissioned after almost 18 years observing the vertical structure and ice/water content of clouds.

As planned, the spacecraft — having reached the end of its lifespan and no longer able to make regular observations — was lowered into an orbit last month that will result in its eventual disintegration in the atmosphere.

When launched in 2006, the mission’s Cloud Profiling Radar was the first-ever 94 GHz wavelength (W-band) radar to fly in space.

A thousand times more sensitive than typical ground-based weather radars, it yielded a new vision of clouds — not as flat images on a screen but as 3D slices of atmosphere bristling with ice and rain.

For the first time, scientists could observe clouds and precipitation together, said Graeme Stephens, the mission’s principal investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

“Without clouds, humans wouldn’t exist, because they provide the freshwater that life as we know it requires,” he said.

“We sometimes refer to them as clever little devils because of their confounding properties.

Clouds have been an enigma in terms of predicting climate change.”

CloudSat, a NASA mission that peered into hurricanes, tallied global snowfall rates, and achieved other weather and climate firsts, has ended its operations.

Originally proposed as a 22-month mission, the spacecraft was recently decommissioned after almost 18 years observing the vertical structure and ice/water content of clouds.

As planned, the spacecraft — having reached the end of its lifespan and no longer able to make regular observations — was lowered into an orbit last month that will result in its eventual disintegration in the atmosphere.

When launched in 2006, the mission’s Cloud Profiling Radar was the first-ever 94 GHz wavelength (W-band) radar to fly in space.

A thousand times more sensitive than typical ground-based weather radars, it yielded a new vision of clouds — not as flat images on a screen but as 3D slices of atmosphere bristling with ice and rain.

For the first time, scientists could observe clouds and precipitation together, said Graeme Stephens, the mission’s principal investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

“Without clouds, humans wouldn’t exist, because they provide the freshwater that life as we know it requires,” he said.

“We sometimes refer to them as clever little devils because of their confounding properties.

Clouds have been an enigma in terms of predicting climate change.”

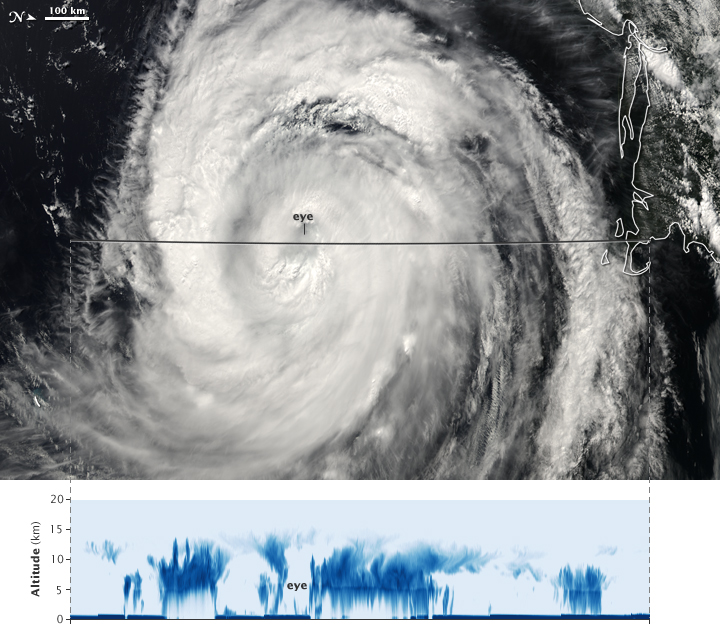

NASA’s CloudSat passed over Hurricane Bill near the U.S.

East Coast in August 2009, capturing data from the Category 4 storm’s eye.

This pair of images shows a view from the agency’s Aqua satellite (top) along with the vertical structure of the clouds measured by CloudSat’s radar (bottom).

Jesse Allen, NASA Earth Observatory

East Coast in August 2009, capturing data from the Category 4 storm’s eye.

This pair of images shows a view from the agency’s Aqua satellite (top) along with the vertical structure of the clouds measured by CloudSat’s radar (bottom).

Jesse Allen, NASA Earth Observatory

Clouds have long held many secrets.

Before CloudSat, we didn’t know how often clouds produce rain and snow on a global basis.

Since its launch, we’ve also come a long way in understanding how clouds are able to cool and heat the atmosphere and surface, as well as how they can cause aircraft icing.

CloudSat data has informed thousands of research publications and continues to help scientists make key discoveries, including how much ice and water clouds contain globally and how, by trapping heat in the atmosphere, clouds accelerate the melting of ice in Greenland and at the poles.

Weathering the Storm

Over the years, CloudSat flew over powerful storm systems with names like Maria, Harvey, and Sandy, peeking beneath their swirling canopies of cirrus clouds.

Its Cloud Profiling Radar excelled at penetrating cloud layers to help scientists explore how and why tropical cyclones intensify.

In this animation, CloudSat’s radar slices into Hurricane Maria as it rapidly intensifies in the Atlantic Ocean in September 2017.

Areas of high reflectivity, shown in red and pink, extend above 9 miles (15 kilometers) in height, indicating large amounts of water being drawn upward high into the atmosphere.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/CIRA

Across the life of CloudSat, several potentially mission-ending issues occurred related to the spacecraft’s battery and to the reaction wheels used to control the satellite’s orientation.

The CloudSat team developed unique solutions, including “hibernating” the spacecraft during nondaylight portions of each orbit to conserve power, and orienting it with fewer reaction wheels.

Their solutions allowed operations to continue until the Cloud Profiling Radar was permanently turned off in December 2023.

“It’s part of who we are as a NASA family that we have dedicated and talented teams that can do things that have never before been done,” said Deborah Vane, CloudSat’s project manager at JPL.

“We recovered from these anomalies with techniques that no one has ever used before.”

Sister Satellites

CloudSat was launched on April 28, 2006, in tandem with a lidar-carrying satellite called CALIPSO (short for the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation).

The two spacecraft joined an international constellation of weather- and climate-tracking satellites in Earth orbit.

Radar and lidar are considered “active” sensors because they direct beams of energy at Earth — radio waves in the case of CloudSat and laser light in the case of CALIPSO — and measure how the beams reflect off the clouds and fine particles (aerosols) in the atmosphere.

Other orbiting science instruments use “passive” sensors that measure reflected sunlight or radiation emitted from Earth or clouds.

Orbiting less than a minute apart, CloudSat and CALIPSO circled the globe in Sun-synchronous orbits from the North to the South Pole, crossing the equator in the early afternoon and after midnight every day.

Their overlapping radar-lidar footprint cut through the vertical structure of the atmosphere to study thin and thick clouds, as well as the layers of airborne particles such as dust, sea salt, ash, and soot that can influence cloud formation.

The influence of aerosols on clouds remains a key question for global warming projections.

To explore this and other questions, the recently launched PACE satellite and future missions in NASA’s Earth System Observatory will build upon CloudSat’s and CALIPSO’s legacies for a new generation.

“Earth in 2030 will be different than Earth in 2000,” Stephens said.

“The world has changed, and the climate has changed.

Continuing these measurements will give us new insights into changing weather patterns.”

More About the Missions

The CloudSat Project is managed for NASA by JPL.

JPL developed the Cloud Profiling Radar instrument with important hardware contributions from the Canadian Space Agency.

Colorado State University provides science data processing and distribution.

BAE Systems of Broomfield, Colorado, designed and built the spacecraft.

The U.S. Space Force and U.S. Department of Energy contributed resources.

U.S. and international universities and research centers support the mission science team.

Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages JPL for NASA.

CALIPSO, which was a joint mission between NASA and the French space agency, CNES (Centre National d’Études Spatiales), ended its mission in August 2023.

Links :

BAE Systems of Broomfield, Colorado, designed and built the spacecraft.

The U.S. Space Force and U.S. Department of Energy contributed resources.

U.S. and international universities and research centers support the mission science team.

Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages JPL for NASA.

CALIPSO, which was a joint mission between NASA and the French space agency, CNES (Centre National d’Études Spatiales), ended its mission in August 2023.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment