Sayula II, rounding Cape Horn, at the 1973-74 Whitbread Round the World Race

Sayula II, rounding Cape Horn, at the 1973-74 Whitbread Round the World Race © Bernardo Arsuaga Private Collection

part 1: Pioneers of the crewed round the world race

This is the first in a series of features celebrating the strong French heritage of The Ocean Race. Produced in cooperation with IMOCA Class, these stories highlight 50 years of the 'French Connection' dating back to the inception of the Whitbread Round the World Race in 1973.

In a year's time, they'll be riding the Indian Ocean swell in The Ocean Race (*) where the IMOCA Class is making its race debut, alongside the familiar VO65 one-designs. Spanning 12,750 miles, or 23,613 km, never before has one leg - between Cape Town in South Africa and Itajaí in Brazil - been so long.

Fifty years ago, sailors from all different backgrounds were competing in the very first crewed sprint around the planet known as the Whitbread Round the World Race.

Half a century on, IMOCA and The Ocean Race are rekindling their ties with this crazy epic in a bid to continue its legacy.

On 8 September 1973, nineteen sailboats from seven nations, a third of which were French, set sail from Portsmouth and the green waters of the Solent bound for South Africa.

Not only was the atmosphere imbued with the inherent stress of any race start, but also a hefty dose of the unknown as the sailors had to negotiate a 27,000-mile sea passage, punctuated by the Roaring Forties and the Furious Fifties in the Indian and then the Pacific Ocean.

The story goes that a few years earlier, the former aviator Sir Francis Chichester, winner at sixty years of age of the first OSTAR, some four years before Eric Tabarly's triumph, came up with the idea of a crewed round-the-world race with some of the UK's leading lights, including Robin Knox-Johnston, winner of the Golden Globe in 1969, and Admiral Otto Steiner.

It was known as the Whitbread Round the World Race as it was sponsored by the famous British brewer.

This first marathon around the planet comprised four long legs from Portsmouth and back via Cape Town, Sydney and Rio.

A certain black boat did not go unnoticed dockside. Pen Duick VI, a 22-metre ketch, was specially designed for the race by André Mauric and was equipped with a depleted uranium keel and titanium components.

The yacht was skippered by Eric Tabarly, who was accompanied by a young and talented crew whose names would soon be familiar to many - Olivier de Kersauson, Philippe Poupon and Marc Pajot...

The majority of the yachts were slow and heavy, loaded to the gunwales with tins of food and jerrycans of water.

Back in 1973, freeze-dried food and watermakers were not available on boats, but they did boast soft berths, back-up heating to try to dry vinyl oilskins from the fishing industry and even slippers.

Back in 1973, freeze-dried food and watermakers were not available on boats, but they did boast soft berths, back-up heating to try to dry vinyl oilskins from the fishing industry and even slippers.

Given the unreliability of the SSB communications, it was considered good form to have both a doctor on board - the future explorer Jean-Louis Etienne on Pen Duick for example - and a cook, who floated between watches and worked at the home-style galley stove.

photo © Dave Leslie

Racer-cruiser yachts as strong as they are comfortable

The British press promises an epic head-to-head battle between Eric Tabarly and Chay Blyth on Great Britain II.

Tabarly had become headline news when he took victory in the 1964 OSTAR, whilst former Paratrooper Blyth had won renown after setting a single-handed round-the-world record against the prevailing winds in a time of 292 days in 1971.

The two sailors were clearly in it to win it.

Recruited by Blyth, his crew were sturdy chaps but hardly sailors, and they complained of having to survive solely on stodgy curry-based meals.

It was borderline mutiny.

Upon making landfall in South Africa, Blyth admitted that "even parachutists are human beings...", which provides some insight into the atmosphere that had developed on board.

It was a very different scenario aboard Sayula II, a Swan 65, designed by the prestigious American firm Sparkman & Stephens, built in Finland and considered back then to be the Rolls Royce of racer-cruisers. Mexican billionaire Ramon Carlin had it all figured out.

It was a very different scenario aboard Sayula II, a Swan 65, designed by the prestigious American firm Sparkman & Stephens, built in Finland and considered back then to be the Rolls Royce of racer-cruisers. Mexican billionaire Ramon Carlin had it all figured out.

He enlisted his son, an amateur yachtsman, but also some brilliant sailors.

Whilst the youngsters got on with the sailing on deck, the skipper and his guests made the most of it.

"We have alcohol aboard and we sometimes have a drink together after dinner or at the end of the watch when we're soaked and chilled to the bone", explained the bon viveur. "Some pay no heed whatsoever to the fact that we have some women aboard (notably Paquita his wife). Their presence in an excellent thing..."

All the same, the legend doesn't really explain how many women there actually were on board and, ultimately, the preferred option was that all of them would step off the boat in Cape Town and join their spouses at the stopovers instead.

A 25-year-old fair-haired boy by the name of Peter Blake

Aboard Pen Duick VI, though, there's a guitar, songbooks and Châteauneuf du Pape - Tabarly's favourite wine - the accommodation is much less cosy, the crew opting to push the boat hard.

A 25-year-old fair-haired boy by the name of Peter Blake

Aboard Pen Duick VI, though, there's a guitar, songbooks and Châteauneuf du Pape - Tabarly's favourite wine - the accommodation is much less cosy, the crew opting to push the boat hard.

The on board footage shows the off-watch crew bounding up on deck in their underpants with no harnesses on to help douse the massive spinnaker during a broach in a fierce squall, the boat rolling from side to side.

It's a miracle that there aren't any casualties.

The race favourite will lose all hope of securing the win when the mast breaks and a new one had to be stepped in South Africa.

This was another crew who spent more time using their toolbox than racing.

On the British-flagged boat, a 25-year-old blond-haired New Zealander is competing in the first of his five consecutive Whitbreads. He goes by the name of Blake and he's enlisted as a general all-rounder.

In his logbook he says: "We've never sailed on this boat before and the race start heralds our first ever sea passage on her! We finish off the interior accommodation in the Solent.

Fortunately, the weather's fine...

However, we fail to check that the heads are disconnected and after a week at sea, we realise that everything's draining into the bilge where the tinned food is stored.

In the panic of the start, we've stowed the tins without referencing them and now the labels have come off so when we open one it's always a surprise!"

Philippe Facque: "I was 21 and I got the opportunity to race around the world!"

Following a month at sea, Sayula II takes the win on corrected time ahead of the comfortable Nicholson 55 named Adventure, and Grand Louis skippered by Frenchman André Viant.

Tragically, three souls are lost at sea, including Frenchman Dominique Guillet, co-skipper of 33 Export, and five boats fail to finish.

The race is merciless and the skipper of the Polish boat Otago, a good seaman but a registered amateur, says out loud what a lot of people are thinking:

"It's really tough to live in such a limited space in very close quarters. Even rats couldn't live on top of one another like that without quarrelling from time to time!"

Listening to Philippe Facque, today the Managing Director of the CDK Technologies yard, and crew for André Viant in 1973, his memories have a rather different flavour.

Two years earlier, and much to the displeasure of his parents, he had traded his A-level oral exams for a shot at his first transatlantic sea passage. With André Viant quickly spotting his talent for driving a boat, he was offered a ride aboard Grand Louis for the first Whitbread.

"I was 21 years of age and I had the opportunity to race around the world. It was just great! In contrast with Kriter helmed by Jack Grout, which only had the big names aboard who didn't get on, there was a fantastic atmosphere on our boat and the unity and trust we felt are essential in a race like this. There were ten of us, with three people on watch at a time - one on deck, one on standby and one in the bunk. It was a mixed crew comprising the family of André Viant, a polytechnic graduate, company director and an incredible sailor - his daughters Françou and Sylvie, his son Jimmy and his son-in-law Michel Vanek... as well as young sailors like Loïc Caradec and me. Grand Louis was a comfortable schooner, but she was a sluggish tank. I recall cooking pancakes to kill time in the Indian Ocean... As it was the first race around the globe, everyone set sail with heavy, solid boats. We didn't know quite what to expect."

Today, despite running the CDK Technologies yard, which has built countless IMOCA yachts, including six Vendée Globe winners and the latest 11th Hour Racing Team, Philippe Facque has never sailed one of these boats.

"I was 21 years of age and I had the opportunity to race around the world. It was just great! In contrast with Kriter helmed by Jack Grout, which only had the big names aboard who didn't get on, there was a fantastic atmosphere on our boat and the unity and trust we felt are essential in a race like this. There were ten of us, with three people on watch at a time - one on deck, one on standby and one in the bunk. It was a mixed crew comprising the family of André Viant, a polytechnic graduate, company director and an incredible sailor - his daughters Françou and Sylvie, his son Jimmy and his son-in-law Michel Vanek... as well as young sailors like Loïc Caradec and me. Grand Louis was a comfortable schooner, but she was a sluggish tank. I recall cooking pancakes to kill time in the Indian Ocean... As it was the first race around the globe, everyone set sail with heavy, solid boats. We didn't know quite what to expect."

Today, despite running the CDK Technologies yard, which has built countless IMOCA yachts, including six Vendée Globe winners and the latest 11th Hour Racing Team, Philippe Facque has never sailed one of these boats.

"What's amazing with these foilers is that they outperform the 60-foot ORMA trimarans from thirty years ago. These boats are fabulous, but with a crew of five in the Southern Ocean, it's bound to be full-on and physically demanding. These carbon hulls are incredible echo chambers. At the same time though, racing has become so much more professional in the past fifty years and today's sailors are meticulously prepared and even 'tougher' than we were. I sometimes wonder whether I'd enjoy a crewed round-the-world race on these extraordinary machines if I were their age today (he's now 70). I think I would... They go three times faster, they certainly do less cooking aboard than we did, but they get to experience what is an exceptional, unique and quite rare adventure," he concludes, laughing.

part 2: The incredible technological laboratory

Flyer, winner of the 1977–78 Whitbread Round the World Race, skippered by Conny van Rietschoten

Flyer, winner of the 1977–78 Whitbread Round the World Race, skippered by Conny van Rietschoten© PPL

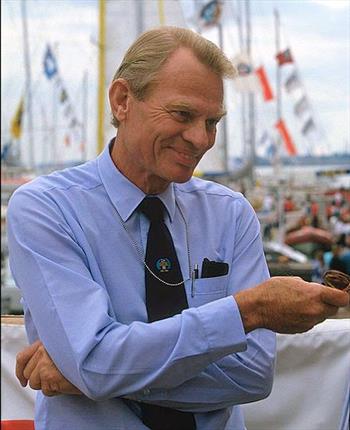

Conny van Rietschoten © Christian Février

In part two of this series devoted to the history of the French in the round-the-world crewed race, IMOCA and The Ocean Race revisit the technological evolution that has coloured a race, which witnessed the first French victory in 1985-86 and the burgeoning career of a certain Franck Cammas.

When Mexican Ramon Carlin snatched glory in 1974 on the Swan 65 Sayula II, others were keen to emulate his performance.

Cornelis 'Conny' Van Rietschoten, a Dutch industrialist, began construction of a 20-metre Sparkman & Stephens ketch, a near sistership to Sayula, albeit made of aluminium, with a longer waterline and carrying more sail area.

Named Flyer, the ketch secured victory in the second Whitbread Round the World Race (1977-78) in 119 days.

By then the race had grabbed the attention of young naval architects, like New Zealanders Ron Holland and Bruce Farr, Frenchmen Philippe Briand, Gilles Vaton, Michel Joubert and Bernard Nivelt, as well as the Argentinian German Frers.

By then the race had grabbed the attention of young naval architects, like New Zealanders Ron Holland and Bruce Farr, Frenchmen Philippe Briand, Gilles Vaton, Michel Joubert and Bernard Nivelt, as well as the Argentinian German Frers.

The Whitbread was not just a fantastic technological laboratory, but also a wonderful showcase for the major yards responsible for production cruising yachts like Nautor Swan, Bowman and Camper & Nicholson.

Some of the more notable innovations tested in the rigours of the Whitbread race included fractional rigs, rigid vangs, honeycomb core bulkheads and twin steering wheels.

In 1981, Rietschoten decided to defend his title with a new boat, Flyer II, designed by German Frers. Somewhat larger (23.16 m), the sloop was an example of the latest trend, fitting out a Maxi IOR (International Offshore Rule) to secure a win on both elapsed and corrected time.

In 1981, Rietschoten decided to defend his title with a new boat, Flyer II, designed by German Frers. Somewhat larger (23.16 m), the sloop was an example of the latest trend, fitting out a Maxi IOR (International Offshore Rule) to secure a win on both elapsed and corrected time.

His crew included Frenchman Daniel Wlochovski in charge of navigation, as well as a 20-year-old New Zealander, Grant Dalton, who designed the sails.

Heart attack in the Southern Ocean

The race was not without incident however. In the South Pacific, Rietschoten came close to tragedy after suffering a heart attack.

Heart attack in the Southern Ocean

The race was not without incident however. In the South Pacific, Rietschoten came close to tragedy after suffering a heart attack.

The skipper forbade his crew from divulging this news and prevented the onboard doctor from contacting a colleague - who happened to be close by aboard rival boat Ceramco New Zealand, skippered by Peter Blake.

"The Kiwis were hot on our heels", Rietschoten explained on his arrival dockside.

"Had they known that I had a health problem, they'd have pushed all the harder."

Miraculously, Rietschoten recovered and Flyer II took the race win, just ahead of Frenchman Alain Gabbay on Charles Heidsieck III and Kriter IX helmed by André Viant. 'Conny' is still the only skipper in history to have won two editions.

photo © DR The Ocean Race

Brittany's youth step up to the plate

Three Bretons, aged between 18 and 21, also had their hearts set on this legendary race.

Teaming up with Gabriel Guilly, they built a 'little' prototype in a shed in Etel in Brittany's Morbihan region.

She measured under fifteen metres and was designed by the Joubert-Nivelt pairing.

She went by the name Mor Bihan.

The trio signed up some renowned sailors: Eugène Riguidel, Philippe Poupon, Jean-François Coste, Halvard Mabire and Jean-François Le Mennec...

Nearly ten metres shorter than Flyer II, Mor Bihan bagged the win on corrected time in the third strenuous leg between Auckland and Mar del Plata.

Eugène Riguidel, skipper for this victorious leg via the Horn, said aloud what many others were thinking: "A race that pits such different boats against one another is doomed. An event with a fixed rating per category would be much better..."

1986, Lionel Péan rather than Éric Tabarly

"The media and authorities hold a tremendous grudge against Bull - a nationalised French company specialising in professional computer systems - for favouring me over Éric Tabarly on his third participation", recalled Lionel Péan. Tabarly was after a Maxi - he had Côte d'Or built - and Bull thought, compared to their 'team spirit' slogan, 'L'Esprit d'Équipe', the double OSTAR champion had an image with a heavy singlehanded bias.

Péan continues: "I realised that the Whitbread wasn't won by the quickest boats, rather it favoured those who make good headway in relation to their handicap.

When we bought 33 Export designed by Philippe Briand, we clipped her wings."

The latter pair knew each other very well and liked one another.

In fact, Lionel went to the same secondary school as Philippe in La Rochelle.

"We had to increase the buoyancy between the measurement points. We kept the same sail area and increased the surface area of the keel, which meant we were highly versatile on every point of sail. It's worth noting that we still had Dacron sails back then. There was no carbon in the hulls. We also had halyards that were a mixture of wire and rope."

This strong skipper sailed with a group of seven young sailors.

"We had to increase the buoyancy between the measurement points. We kept the same sail area and increased the surface area of the keel, which meant we were highly versatile on every point of sail. It's worth noting that we still had Dacron sails back then. There was no carbon in the hulls. We also had halyards that were a mixture of wire and rope."

This strong skipper sailed with a group of seven young sailors.

He had a floating position aboard, as did the guy doing the cooking, rotating each day.

"We sailed our outward and return leg of the Atlantic at an average of 7.8 knots, and the two legs from Cape Town-Auckland and Auckland-Punta del Este at 9.8 knots, on a boat measuring just 56 feet and dating back to 1981.

Today, when you see the performances posted by IMOCAs, you get the sense that our boats were "Retromobiles"!

Everyone carried heavy packs of mineral water and tinned food galore, and we were the only ones to set sail with just an industrial watermaker.

Everyone carried heavy packs of mineral water and tinned food galore, and we were the only ones to set sail with just an industrial watermaker.

It was enough to produce our water and prepare the freeze-dried food. In IOR, the boats were measured empty so it was important to keep weight to a minimum."

Seventeen days without seeing the horizon

"It was the early days of SATNAV and, when it worked, we had a position about every four hours... In the Deep South, upon setting sail from Auckland, we spent 17 days in a complete pea-souper, so it was impossible to use the sextant."

Before leaving New Zealand, Péan put an extra five spinnakers aboard, so he had eleven in all.

Seventeen days without seeing the horizon

"It was the early days of SATNAV and, when it worked, we had a position about every four hours... In the Deep South, upon setting sail from Auckland, we spent 17 days in a complete pea-souper, so it was impossible to use the sextant."

Before leaving New Zealand, Péan put an extra five spinnakers aboard, so he had eleven in all.

After completing a circumnavigation of the globe outstandingly well, Lionel Péan and his crew became the first French sailors to win the Whitbread, completing the course in 111 days.

Cammas discovers sailing through Tabarly's book about the Whitbread

Since its creation in 1973, the Whitbread has inspired a whole generation.

Such is the case for one young schoolboy born a year before the first edition, who loved hanging around in a bookshop in Aix-en-Provence after lessons

He came across a book entitled "Le tour du monde de Pen Duick VI" (Pen Duick VI's circumnavigation of the globe) by Éric Tabarly, which his father gifted to him.

"I'd never gone sailing in my life and I didn't understand much about it as there were a lot of technical terms. I re-read it three or four times over the summer whilst we spent our holidays in the Alps... with a dictionary to hand. I was so inspired by the book that I kept badgering my parents, who were more mountain than sea, to sign me up for a beginner's course on an Optimist in Marseille."

Not yet ten, this kid was called Franck Cammas.

Not yet ten, this kid was called Franck Cammas.

From his opening tacks on the water, he was smitten, and onlookers were impressed by the speed with which he learned how to sail.

"Fairly quickly, I told myself that the most fantastic thing would be to compete in this race one day."

After his record-setting voyage in the Jules Verne Trophy and the Route du Rhum in 2010, the sailor from Aix-en-Provence was preparing to compete in the most prestigious of round-the-world races, the Volvo Ocean Race.

In preparation for the start, at the end of 2011, he acquired the winning boat from the previous edition, Ericsson.

In preparation for the start, at the end of 2011, he acquired the winning boat from the previous edition, Ericsson.

He formed an entourage of specialists in the event, including a number of Anglo-Saxons to get a better understanding of the subtleties of this unique challenge, putting together a crew combining specialists from the round the world race, the Solitaire du Figaro and close-contact racing.

Cammas launched a new boat, Groupama 4 designed by his team and the Argentinian naval architect Juan Kouyoumdjian, who'd learned his craft with Philippe Briand.

Those familiar with the crewed round the world race weren't suspicious of this sailor.

He may have already earned a lot of wins in solo format, but this time he was discovering a world he didn't know. Indeed, during the first leg, he was still in learning mode.

With the passing miles though, Groupama 4 evolved and the team upped their game before taking the lead and winning the eighth and penultimate leg between Lisbon and Lorient...

During the French stopover, whilst the overseas crews headed off for a round of golf or to have some fun, Cammas and his team further optimised their boat, to the extent that they cut away the companionway steps to save a few extra grams before the final sprint to Galway.

During the French stopover, whilst the overseas crews headed off for a round of golf or to have some fun, Cammas and his team further optimised their boat, to the extent that they cut away the companionway steps to save a few extra grams before the final sprint to Galway.

The French team sailed an absolute blinder and Franck Cammas took victory in the Volvo Ocean Race in 2012, something which his idol Éric Tabarly was not able to do.

Aboard the boat was a certain Charles Caudrelier, helmsman-trimmer, who would go on to be promoted to the rank of skipper of Dongfeng Race Team, a French-Chinese campaign.

Aboard the boat was a certain Charles Caudrelier, helmsman-trimmer, who would go on to be promoted to the rank of skipper of Dongfeng Race Team, a French-Chinese campaign.

He too secured a win two editions later (2017-18) at the head of an accomplished international crew.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment