From Morning Brew by Greace Donnelly

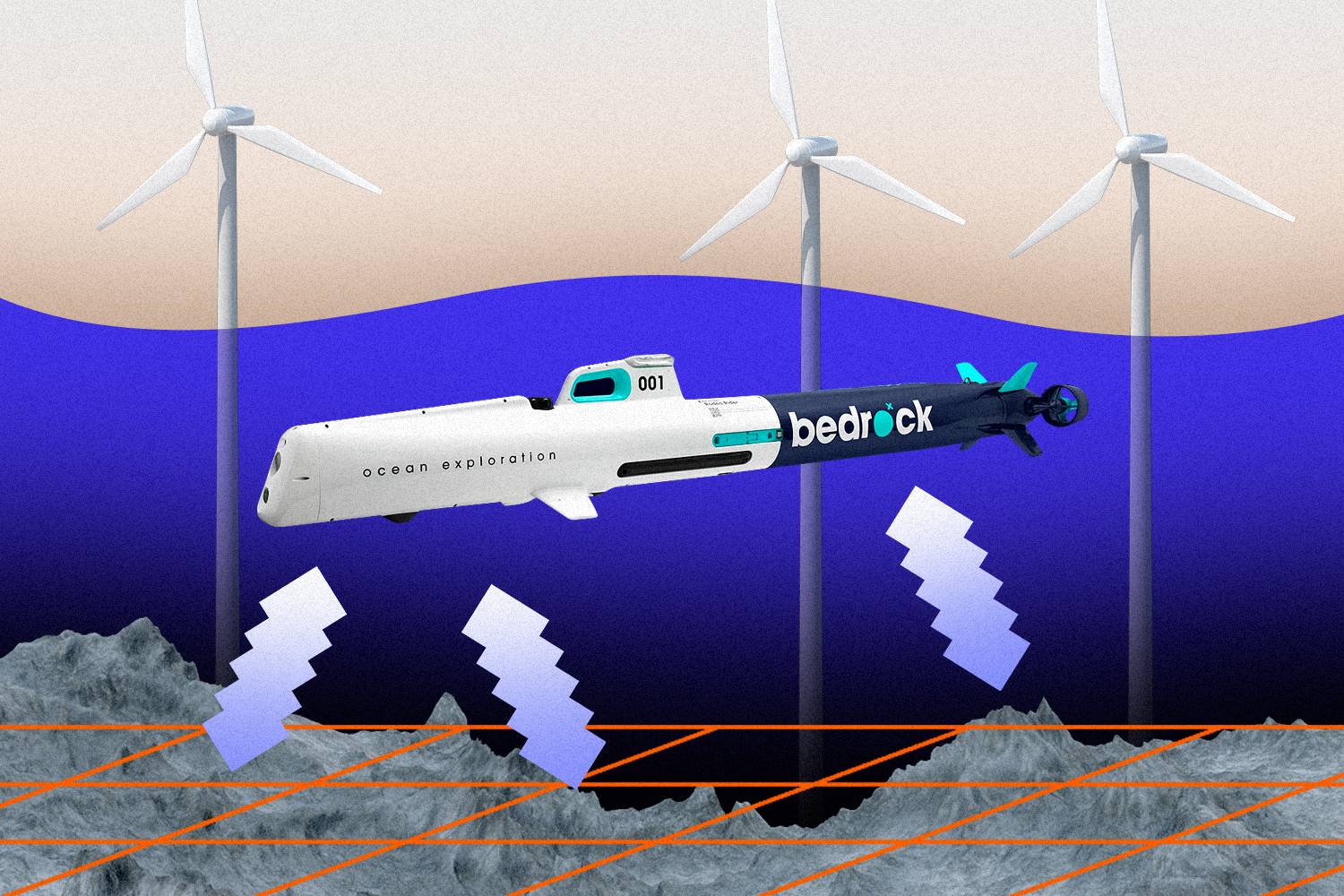

Bedrock,

an early-stage startup, wants to shrink the time it takes to map the

ocean floor—a key step in rolling out wind turbines.

Francis Scialabba

Nearly every time humans go into the deep sea, we discover new species.

Scientists estimate that we have classified as little as 9% of all marine life.

And the mystery extends beyond life and to topography, too—at present, we’ve only mapped about 20% of the Earth’s seabed.

Making progress on the latter point—seafloor mapping—is crucial to measuring climate change and deploying ways to combat it.

“The data we collect connects to climate science, site assessment for wind-energy farms, site assessment for potential marine resources, habitats, fisheries, marine management—anything like that,” Rachel Medley, chief of the expedition and exploration division at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), told Emerging Tech Brew.

But the process of scanning the seafloor is expensive and time-consuming.

Bedrock, a two-year-old, Brooklyn-based startup, aims to make the process up to 10 times faster with its electric, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) that can navigate along the ocean floor in waters up to 300 meters deep.

Bedrock is still in the early stages of testing this tech—it has only built one AUV so far—but it raised $8 million in a seed round last March and is hiring “aggressively” to grow the current team of ~20 full-time employees, its CEO and co-founder, Anthony DiMare told us.

To begin with, the startup is tailoring its tech to the seafloor-mapping needs of the offshore-wind industry, which is gaining some momentum in the US.

The Biden administration is pushing to add 30 GW of offshore wind power by 2030.

That would mean about 2,000 turbines along the coast of the US.

Right now, there are only seven.

Meeting that 2030 target could trigger $12 billion in annual investments in domestic offshore wind projects, and help accelerate wind power’s prominence in the US electrical mix, from about 8% today to 20% in 2030.

In addition to the one AUV in use now, another is being built.

Bedrock began construction on its own production facility in Richmond, California, at the end of 2021 and aims to build at least 25 of its AUVs by the end of the year, DiMare told Emerging Tech Brew.

These battery-powered AUVs can operate for 24 hours at a time and typically travel at speeds of about 2 to 3 knots (~2 to 4 miles per hour).

Searching the seabed

Before any turbines go into the water, offshore wind developers have to determine the landscape of the seabed, catalog the species living in the area, and measure potential environmental impacts.

Seafloor mapping today requires deploying a large, manned ship and using sonar-equipped devices and autonomous surface vessels to collect data about water depth and temperature, as well as the landscape and sedimentary makeup of the ocean floor.

For offshore wind developers, this means a 200- to 300-foot, highly specialized ship that can operate 24 hours a day.

“We’ll start with a broad oceanographic survey that will include what we refer to as marine geophysical and geotechnical information,” Jesse Baldwin, head of US site investigation at offshore wind developer Ørsted, told Emerging Tech Brew.

“We’re collecting a lot of that remote sensing data.”

This initial survey usually takes about six months and the process costs tens of millions of dollars, Baldwin said.

DiMare believes Bedrock’s tech can address several of the bottlenecks in the current mapping process.

Rather than waiting weeks or months for a massive ship to sail to the area you need to survey, Bedrock’s AUVs are small enough to be shipped or even checked as luggage on a flight and can be launched directly from the shore without the need for a boat.

“I’m trying to help enable that at a 10 times faster rate than what they’re doing now,” DiMare said of Bedrock’s technology.

In other words, if the current process takes about six months, Bedrock aims to shrink that to about three weeks.

Medley, who co-chairs one of the interagency working groups collaborating on an effort to map the outer boundary of the US seabed by 2030, says AUVs can play a role in collecting seafloor data.

NOAA already uses autonomous technology for some tasks, but Medley doesn’t necessarily see them as a replacement for ships.

"All autonomous systems complement ship activities,” she said.

“And usually, you can use them as a force multiplier, to be able to achieve a broader goal, rather than just doing it with one particular platform."

And as more wind farms are built, companies will also need a way to check on the integrity of their turbines during construction and over their lifespan afterward.

“I do think that there is certainly going to be an avenue for companies like ours to use autonomous solutions in the future,” Baldwin said, with the caveat that these technologies will have to be able to meet Ørsted’s data quality standards.

For now, the company still uses traditional ocean survey equipment, which is either mounted directly to the ship or towed behind it, he said.

Bedrock says it’s currently working with one customer in the offshore wind industry as well as another renewable energy customer and ocean and earth science companies, but declined to name any clients.

Although the company is focused on offshore wind, AUVs could also be used to build the maps needed for ocean carbon sequestration, laying telecom cables, underwater data centers, and decommissioning oil and gas pipelines, Bedrock says.

And by getting its AUVs closer to the seabed, the company says it can use a higher-frequency sonar for these missions that is less likely to disturb marine life than the signals sent out by vessels on the surface.

Deep-sea data

Under the traditional methods, managing the enormous datasets collected by ships that don’t always have an internet connection can be slow and complicated.

Even onshore, sharing terabytes of seafloor mapping data among stakeholders can be cumbersome.

NOAA makes its information publicly available, but DiMare said his request for NOAA’s data on the seafloor off the coast of New York took three weeks and involved shipping physical hard drives.

NOAA told us hard drives are only used for large data requests, and even then only if a user explicitly requests the physical process rather than a piecemeal download.

Along with the AUVs, Bedrock says it is building a platform for its customers to more easily process and share the data collected about the seafloor, though it’s not technically possible to transmit the full datasets from their point of collection via today’s wireless methods.

“This will be one of the largest geospatial datasets in existence and we are collecting it in the least connected part of the world,” DiMare said.

“So the challenges will exist around figuring out how to manage fleets—thousands of [AUVs]—get them recharged, and then get data back to land, where we can use cloud systems to make intelligent decisions.”

If Bedrock is able to deliver on that vision—to build a system that can efficiently provide a detailed understanding of the bottom of the ocean—it could be a boon not only to business, but also to science more broadly.

The company is also involved in an international effort called Seabed 2030, that aims to map the entire ocean floor by the end of the decade.

DiMare hopes someday the world will have a fresh seafloor map each year.

“What is most exciting to me is we are going to find things and discover things and be able to do things that we’ve never been able to do before,” he said.

“There’s not too many other environments, spaces, data gaps of this magnitude, where you just don’t know what we’re going to find.”

- GeoGarage blog : Bedrock modernizes seafloor mapping with ... / The future of ocean exploration

YouTube : Bedrock : about us

ReplyDelete