Indonesian President Joko Widodo aboard a navy ship visits a military base in the Natuna Islands in January 2020.

Photo: Handout

Photo: Handout

From SCMP by Resty Woro Yuniar

Foreign minister Retno Marsudi says Indonesia will increase efforts to accelerate the demarcation of both land and sea boundaries

Boundary disputes must be resolved using international law, she says, echoing a stance Jakarta has taken on the South China Sea

When Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi announced her ministry’s targets for this year, she said the country would intensify negotiations to resolve border disputes with nations including Malaysia and the Philippines.

Indonesia, an archipelago of more than 17,000 islands, has decades-long land and maritime boundary disagreements with its neighbours.

Retno, who also highlighted her ministry’s achievements from last year, said boundary disputes needed to be resolved using international law.

This is a stance Southeast Asia’s largest economy, and founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, has also taken towards the South China Sea dispute.

A map of the South China Sea showing China’s nine-dash line and Indonesia’s Natuna Islands.

Image: SCMP

Image: SCMP

Indonesia views itself as a non-claimant state in the dispute that Beijing, Taipei and four Southeast Asian states have over the resource-rich waters.

However, an area between peninsula Malaysia to the west and the island of Borneo to the east that Indonesia claims as part of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) does fall within Beijing’s nine-dash line.

Fishing vessels from both China and Vietnam frequently visit the waters around Indonesia’s Natuna islands.

Retno said 17 rounds of negotiations were conducted with the Philippines, Malaysia, Palau, and Vietnam last year.

“It is interesting to note that the total number of negotiation rounds conducted in pandemic times has [more than] doubled from 2020, [when there were] only seven rounds,” she said.

“In 2022, efforts to accelerate land boundaries demarcation and maritime boundary delimitation will be intensified,” she added, referring to the marking or describing of boundary limits.

What are Indonesia’s border negotiation targets this year?

In 2022, Indonesia will focus on four maritime boundary issues it has with neighbouring countries, Retno said.

Firstly, regarding Malaysia, she said Indonesia hopes “treaties on the delimitation of territorial waters in the Sulawesi Sea and in the southernmost part of the Strait of Malacca can be signed.”

Indonesia’s focus this year includes trying to resolve boundary issues with Malaysia.

Image: SCMP

Image: SCMP

Indonesia also hopes to begin negotiations “for the delimitation of the continental shelf at the technical level and to follow up on the agreement to delimit the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones with two separate lines” with the Philippines, Retno said, and resume negotiations with Vietnam to reach an agreement on the EEZ boundary line in waters near the South China Sea.

It also aims to reach a partial agreement on EEZ establishment with Palau, she said.

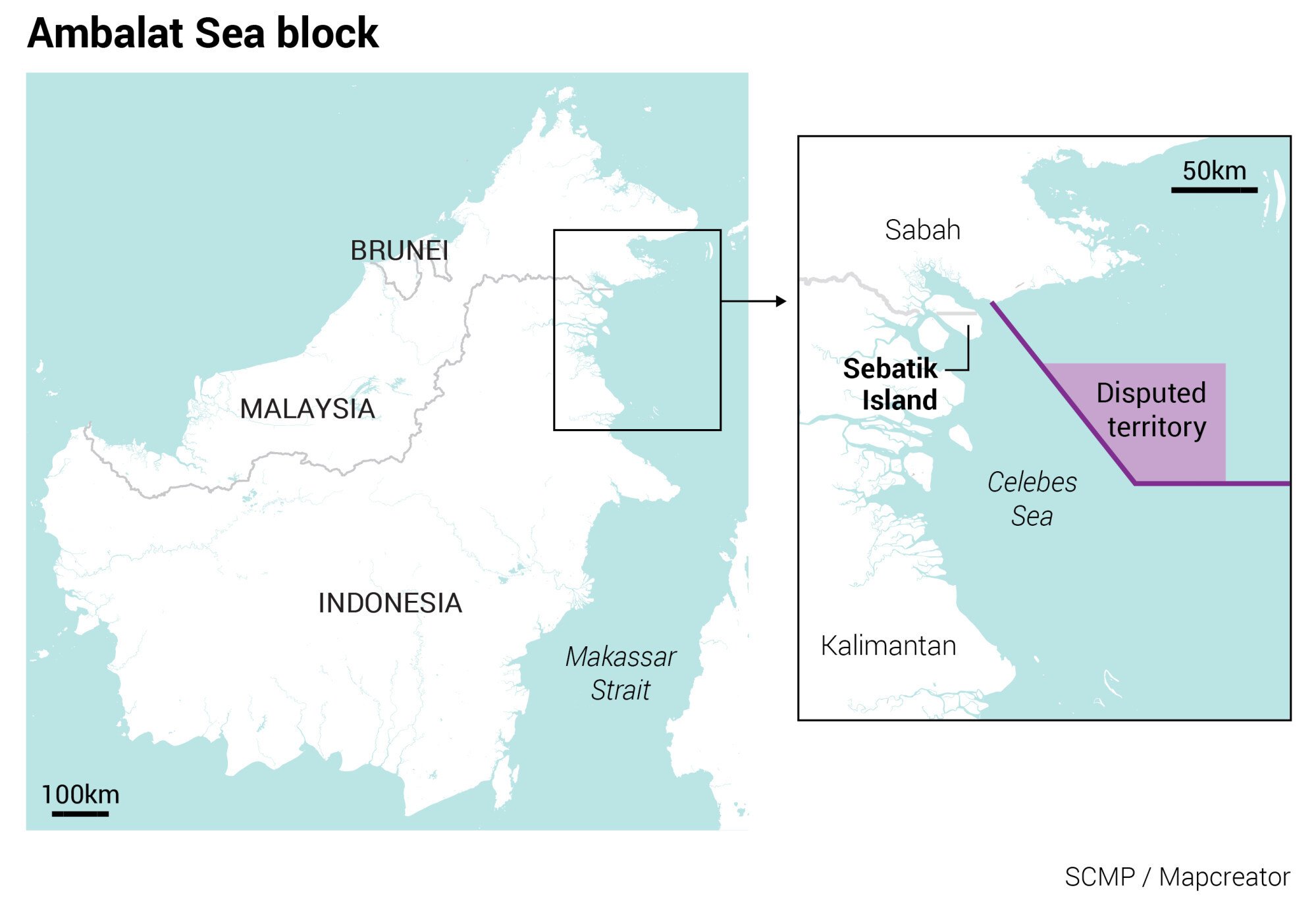

In relation to land boundaries, Jakarta also hopes to resolve demarcation issues related to outstanding boundary problems in the “eastern sector including Sebatik Island”, Retno said, referring to an outlying island off the eastern coast of Borneo.

The northern part of the island belongs to Malaysia and the southern part to Indonesia.

It also hopes to resolve disagreements over two sections of its border with East Timor, she said.

Indonesia controls West Timor, part of the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara, while East Timor – the east side of the island of Timor – is an independent nation.

What’s the Indonesia-Malaysia border dispute about?

In 1969, Indonesia and Malaysia agreed to a continental shelf boundary and a territorial sea boundary in the Malacca Strait and in the Natuna Sea portion of the South China Sea, on both the western side – off the coast of West Malaysia – and eastern side, off the coast of Sarawak.

But beyond that, the continental shelf and territorial sea boundaries in those waters have not been agreed on.

The 1969 treaty followed guidelines laid out by the 1958 Convention on The Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, which did not include guidelines on how to establish EEZs for coastal countries.

Indonesia ratified the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1985, which says a coastal country’s EEZ can extend up to 200 nautical miles offshore.

‘In the name of humanity’, Indonesia welcomes Rohingya refugees found adrift on broken boat

The agreement on the continental shelf and territorial sea boundaries that Indonesia and Malaysia signed in 1969 did not include details about Indonesia’s EEZ.

Malaysia views the treaty as the only one it has with Indonesia on maritime boundaries, as well as a tool that Indonesia can use to determine its EEZ.

According to Indonesia’s calculations, it is entitled to an extra 14,030 sq km of waters in the resource-rich area, if both countries agreed to the guidelines set out by UNCLOS.

“At stake are the abundant resources offered by these waters, but difference of perceptions between Indonesia and Malaysia have made it hard for them to discuss the maritime boundaries in the region,” said Fauzan, an international relations lecturer at Universitas Pembangunan Nasional in Yogyakarta focusing on border management and security.

Indonesia has underlined that it will strictly adhere to UNCLOS going into negotiations with Malaysia this year, with Retno saying Indonesia “will continue to reject any claims lacking an international legal basis”.

What about the Celebes Sea?

In this oil-rich region, Indonesia and Malaysia have no maritime boundary agreement.

In 1979, Malaysia unilaterally drew a map that depicted its territorial sea and continental shelf border, which included an area in the Celebes Sea, off the coast of Borneo.

Indonesia did not recognise this map and later said it owned the area of sea, calling it Ambalat.

Little did the two countries know that this dispute would blow up into one of their most thorny bilateral issues since Indonesia’s founding father Sukarno declared his anti-Malaysia stance in the early 1960s.

|

| Indonesia and Malaysia both claim an area, which Indonesia calls Ambalat, in the Celebes Sea. Their dispute over it has gone on for years. Image: SCMP |

In 2005, Indonesians took to the streets to protest Malaysia’s claims to Ambalat, after the latter’s state-owned oil and gas firm Petronas granted oil company Shell exploration rights in and around the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands, encroaching on the Ambalat area.

The dispute also led to a military stand-off, with Indonesia deploying four fighter jets to East Borneo after Malaysia sent patrol boats, warships, and air squadrons to the area.

In 2005, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono visited a marine post on Sebatik Island.

The territorial dispute prompted Indonesia and Malaysia to deploy warships and fighter jets at the time.

Photo: AFP

The territorial dispute prompted Indonesia and Malaysia to deploy warships and fighter jets at the time.

Photo: AFP

In 2002, the International Court of Justice awarded the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands to Malaysia, but did not determine the maritime boundary in the surrounding waters.

The ownership of Ambalat, therefore, needs bilateral negotiations on the region’s maritime limits.

How about Indonesia and Malaysia’s land borders in Borneo?

The demarcation process so far has adhered to provisions in delimitation agreements agreed by British and Dutch colonial governments in 1891, 1915, and 1930.

Sebatik Island occupies around 452.2 square km and is located about 1km from mainland Borneo.

The northern part of the island belongs to Malaysia’s Sabah state, the southern part to Indonesia’s North Kalimantan province.

Indonesian Sebatik has 47,000 people, while Malaysian Sebatik has around 25,000.

A demarcated international border between the two countries has not been established in the eastern part of the island, including its maritime area.

The island reportedly has abundant – but untapped – oil deposits.

What about Indonesia’s demarcation efforts with the Philippines and Vietnam?

Indonesia and the Philippines have, since 2019, ratified EEZ boundary agreements that were initially signed in 2014, following a 10-year process.

The EEZ boundary is around 627 nautical miles long, taking in the Celebes Sea and the Philippine Sea, and is set out through eight geographic coordinate points.

In October last year, the Philippines and Indonesia held a preparatory meeting about the delimitation of the continental shelf boundary, in which both sides agreed to adhere to UNCLOS.

The two countries plan to hold an in-person meeting this year of their Joint Permanent Working Group on Maritime and Ocean Concerns on the Delimitation of Continental Shelf.

Indonesia agreed on a continental shelf boundary agreement with Vietnam in 2003, that produced a border around 250 nautical miles long.

However, both countries have yet to reach an agreement regarding EEZ delimitations in the South China Sea.

As a result, parts of Indonesia’s EEZ around the Natuna Islands is repeatedly encroached upon by Vietnamese fishermen, which sometimes leads to diplomatic protests by Jakarta and Hanoi.

These fishermen have been detained by Indonesian authorities in the past.

No comments:

Post a Comment