Victor Vescovo

Victor Vescovo wanted to be the first person to reach the deepest points of all five oceans – but first he had to build a submarine that was up to it

Victor Vescovo is ready to make history.

It’s 12.37pm on Saturday August 24, 2019, and the 53-year-old Texan is about to attempt to pilot his bespoke submersible to the bottom of the Molloy Deep, a nodal basin (one that is unaffected by tidal movements) 5,550 metres deep, located in the Fram Strait, between the Arctic Ocean and the Norwegian and Greenland Seas.

To arrive here, 48 crew members and passengers on the research vessel DSSV Pressure Drop have sailed 17 hours from the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard into the open expanse of the Arctic Ocean.

By diving down to the seabed, Vescovo hopes to become the first person in history not only to touch down on the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, but to have explored the deepest point of all five of the Earth’s oceans.

The Five Deeps expedition got under way in December 2018, when Vescovo took his submersible, called Limiting Factor, to the 8,376m depths of the Atlantic Ocean’s Puerto Rico Trench.

Since then he has made contact with the Antarctic Ocean’s 7,433m South Sandwich Trench, the Indian Ocean’s 7,192m Java Trench, and the Pacific Ocean’s 10,925m Mariana Trench, en route to his last stop at the top of the world.

This final Five Deeps dive is the culmination of over four years of planning.

It is an odyssey that has seen Pressure Drop cover 46,262 nautical miles, employing hundreds of research scientists, expedition staff, engineers and ship’s crew at a cost of millions of dollars – a bill footed by Vescovo, who operates a private equity firm when he isn’t venturing to the Earth’s most remote places.

The success of the project depends on this final dive.

Vescovo has a three-day window before a storm is set to arrive over the Molloy, bringing with it three-metre waves and 40-knot winds.

Miss this opportunity, and he will have to wait another year.

Today, dive day, the wind chill factor contributes to an air temperature of -8C, and the water temperature is just 0.4C.

It is, as a crew member remarks, “as cold as water gets before it freezes”.

Before Vescovo even begins his descent to the bottom of the ocean, the pressure is immense.

Limiting Factor – a titanium machine that resembles more a squashed milk carton with two eye-like portals than a traditional cylindrical submarine – has been manoeuvred into position by a huge metal A-frame launcher, and is now suspended securely over the back of the ship, awaiting its lone passenger.

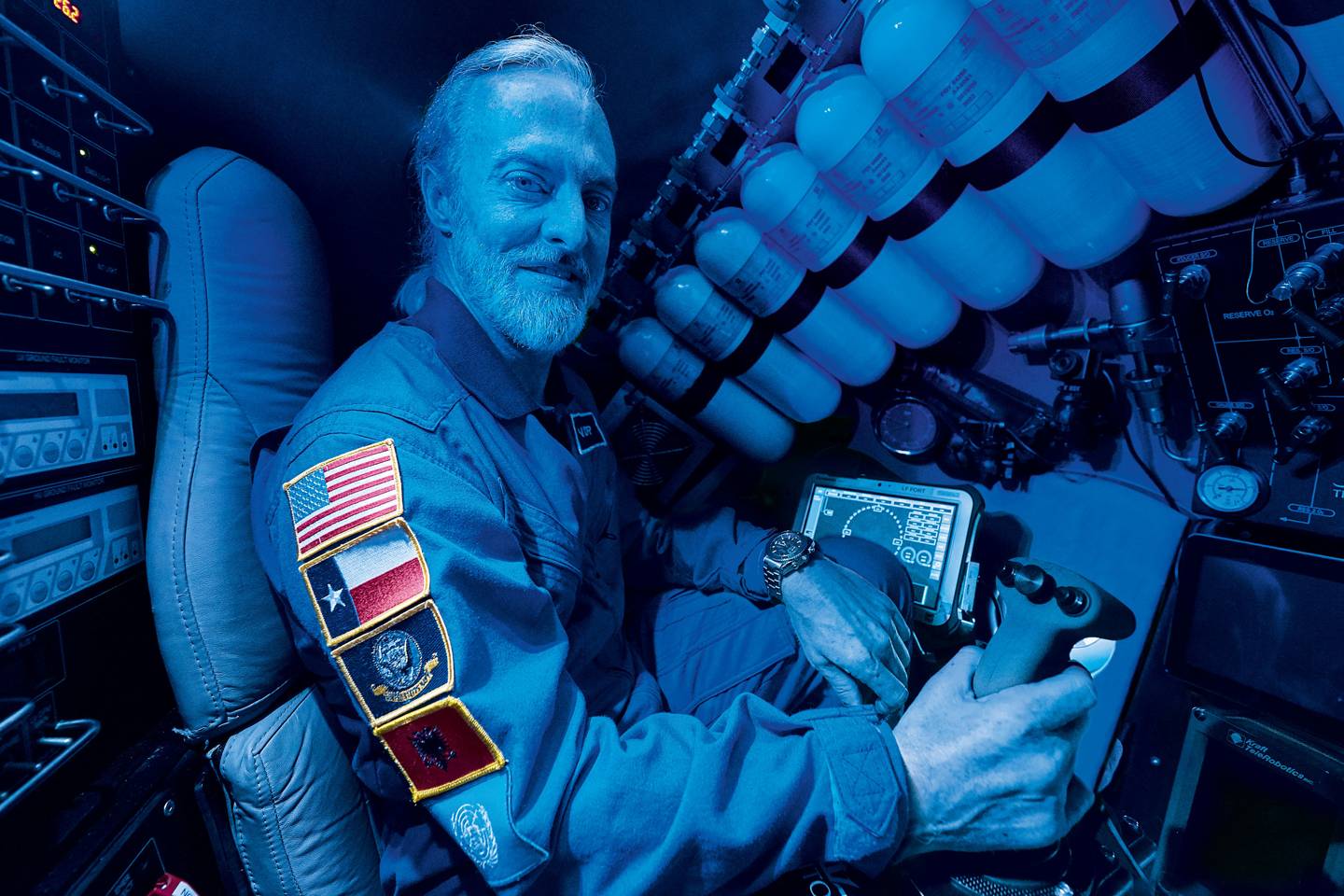

With safety and systems checks completed, Vescovo emerges on to the aft main deck, dressed in blue overalls with a cream cardigan visible at the neck.

A patch on his chest reads "Vescovo"; on his right arm are the Texas and US flags.

His metallic blonde hair is tucked beneath a black beanie, and his grey beard is split by a sharp-toothed smile.

He moves around the deck, shaking hands.

“Last one,” he repeats to each crew member.

It is easy to picture him, in a parallel life, preparing to blast off into the far reaches of space.

Vescovo’s submersible is the first to be designed for repeat visits to such depths.

On the darkness of the ocean floor, this 11.7-tonne vessel, 4.5 metres long, will be his single link with the world above.

Should anything go wrong, there will be no escape.

More than 5,000 metres below the surface of the ocean, there are no footsteps to follow in, no safety ropes for guidance.

This final dive must be undertaken alone.

With the submersible ready to launch, Vescovo clambers onboard.

Before he climbs inside, he holds up an index finger – "one", representing the last dive standing between him and history.

He disappears inside the shiny white hull.

Hatch secured, Limiting Factor is lowered into the iron-green ocean, a current buffeting its sides.

A swimmer, encased in a thick, Arctic-proof wetsuit, balances on top of the vehicle, disconnecting safety lines before diving into the ocean and swimming to a waiting Zodiac boat.

With all eyes watching, the submersible begins to sink beneath the swell, its hull disappearing, an orange flag waving above the surface to indicate its position.

Soon there is only a brief patch of oxidised teal ocean where the sub once was.

Then that too washes away, as submersible and pilot sink into the depths.

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

Vescovo operated his first vehicle in 1969, when he was just three years old.

Stealing away from his parents at the family home in Dallas, Texas, he climbed into the front seat of their car, put it into neutral, and rolled on to a nearby highway.

What happened next was, he says, “a really bad accident”.

Miraculously, no one else was hurt, but the three-year-old Vescovo was crushed inside the car.

He spent six weeks in intensive care, his skull was fractured in three places, and he required 100 stitches.

Although he slowly recovered, he still does not have any feeling in the side of his right hand.

“My dad said the Lord saved me,” he says.

“But I just thought I’d been lucky.

I realised then that we were all living on borrowed time.”

We’re talking inside Vescovo’s generous cabin on board Pressure Drop.

On the walls are half a dozen photographs of waves by French photographer Pierre Carreau.

The bookshelves hold a selection of sci-fi titles; both Pressure Drop and Limiting Factortake their names from sentient spaceships in Iain M Banks’s Culture series.

Growing up, a sci-fi obsessed Vescovo had hoped to graduate from purloined cars to fighter jets.

A failed eye test put the brakes on that plan, so he made a detour into aerospace design at Stanford.

But it wasn’t for him.

“I could do it but I wasn’t that good at it,” Vescovo shrugs.

He switched to a double major in economics and political sciences, and has continued detouring ever since.

He has worked in finance on Wall Street and in Saudi Arabia, management consultancy in Dallas, and at a dotcom era startup in San Francisco.

He served as a reserve intelligence officer in the US Navy from 1993 to 2013, supporting combat operations in Serbia from the Nato HQ in Naples, Italy, as well as rear-area HQs in South Korea and the Persian Gulf.

In 2002, he finally settled in private equity, amassing enough money to fund a climbing hobby that took him to the Seven Summits – the highest mountains of each continent – followed by expeditions to both poles.

Having thus completed the “Adventurer’s Grand Slam”, Vescovo alighted on the idea of diving thanks to the influence of another affluent businessman with a thirst for adventure.

Richard Branson had been talking about his plans for Virgin Oceanic, a commercial project designed to take customers to the deepest parts of the five oceans, since 2009; he saw it as “the last great challenge for humans”.

Although the Virgin project was mothballed in 2014 due to difficulties in developing the necessary technology, Vescovo knew he had found his next mission.

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

“Branson chose a technology that was going to be based on carbon fibre.

It was a little out there,” Vescovo says.

“But I couldn’t believe no one had ever tried it – that no person had ever been to the bottom of four of our oceans.

It was obviously possible, because James Cameron did it in the Mariana Trench in 2012.

I thought, how hard could that be?”

Initially, Vescovo thought he’d just buy Cameron’s sub, refurbish it, and dive in it to the bottom of the oceans.

But he judged Cameron’s tech to be out of date, requiring too many costly upgrades.

Deciding that what he really needed was his own craft, he reached out to Patrick Lahey, president of Florida-based Triton Submarines.

Born in Ottawa, Canada, in 1962, Lahey has been diving since 1975 and has almost 40 years of commercial underwater experience.

He co-founded Triton in 2008.

When Vescovo got in touch about building a deep-sea vehicle that could reach the bottom of five oceans, he saw it as a chance to realise a long-held ambition.

“It’s something we always wanted to do,” he says.

Their first meeting took place in May 2015, when Vescovo flew to the Bahamas to attend a dive with Lahey and Triton’s principal design engineer, John Ramsay.

Vescovo outlined his desire for a submersible that could simply go down and come back up again; anything else was superfluous.

“I said: ‘The design needs to be the AK-47 principle.

It needs to be functional and reliable, and work.

Don’t go off the reservation with bells and whistles.

Make it simple and reliable,’” Vescovo says.

As far as Triton was concerned, this initial brief was a little too simple.

“His original concept was a steel sphere with no windows,” Lahey says.

“We weren’t interested in building that.” For Triton, the submersible (officially designated the Triton 36,000/2) had to have commercial applications so that further models might be sold after Vescovo’s dives.

For this to happen, it would need two seats (to accommodate a pilot and a scientist), a manipulator arm and, crucially, windows instead of the system of external cameras and internal screens Vescovo initially proposed.

“The whole point of a human-manned submersible is that it’s a visual tool,” Lahey says.

“There’s no way you can duplicate our sense of sight.

When you’re down there looking out that window, it’s like you’re hardwired to your eyeballs.

You drink information in in a different way.

There’s an immediacy to it, and an effectiveness.” Eventually Vescovo agreed, and signed Triton up to design his one-of-a-kind machine.

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

As principal design engineer, Ramsay, a 39-year-old from north Lincolnshire, was tasked with bringing Vescovo’s vision to life – starting with the windows.

Every submersible contains a pressure hull in which the pilot is encased.

In this instance, the most protective shape was a spherical control centre, with the wiring, mechanics and foam buoyancy aids stored outside in the main body of the vessel.

The difficulty Ramsay and his team faced was that, if you punch a hole in this sphere for windows, you create an uneven shape, which is at risk of buckling under oceanic pressure.

And at 11,000 metres, Vescovo’s deepest dive, that could be fatal.

“Windows are a monstrous design exercise,” Ramsay says.

“Making sure they don’t pop the viewports out, or collapse in, is a literal balancing act of stresses.”

He opted for a unique solution: three 200mm-thick conical windows made from acrylic.

To accommodate the immense 110.3 megapascal pressures acting on the window surface at 11,000 metres, the windows taper, with a degree of empty space between them and the sides of the window casing.

This means that, by a depth of 6,000m, the windows have been forced inward 7mm due to outside pressure.

Without this ability to move, stress would collect at certain points, potentially causing fractures that would compromise the sub’s integrity.

Another consideration was the shape of the submersible.

Most are organised lengthways, with a narrow viewing portal and the pilot’s sphere at the front of a long tube, but this limits the vehicle’s movement to left and right.

On commercial or oil industry dives, this doesn’t matter so much, but in the mostly un-plunged depths of the five oceans, it was important that Vescovo’s sub had as much manoeuvrability as possible, both to aid navigation around uncharted terrain and to offer the best viewing opportunities of sea floor flora and fauna.

To that end, Ramsay searched for shapes that were streamlined in both directions, eventually taking inspiration from rugby balls and bullet trains.

“We spun the sub 90 degrees and had it totally symmetrical,” he says.

“That means you can get amazing manoeuvrability and maintain that elliptical shape.

When you’re on a vertical dive site it’s easy to shift side to side and up and down, as it’s streamlined in those directions.”

Triton outfitted Limiting Factor with ten thrusters, allowing it to move up and down, to port and starboard, forward and back.

But even the thrusters presented a new challenge.

“The biggest fear of any submersible pilot is nets or ropes getting sucked into the thrusters,” Ramsay explains.

“Usually, you’d have a rescue sub that could get down with a manipulator arm and cut you free; with the Limiting Factor that’s impossible.

By the time you're past 6,000 metres, no one is going to rescue you.

Get tangled on a bit of fishing net hooked on some rocks and you have no chance.”

The solution was simple but elegant.

The submersible already had external battery packs which could be separated from the body by an explosive bolt (one that can be electrically actuated to break), in case it needed to shed weight quickly to return to the surface.

The thrusters would be attached by the same type of bolt.

Should the sub become entangled, all Vescovo would need to do is activate the eject mechanism, and the thrusters would separate and float away, casting the vessel free.

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

As for the interior components, designers can usually borrow off-the-shelf parts from the oil and gas industry.

But their subs rarely dive deeper than 6,000 metres, meaning Ramsay and Triton’s principal electrical design engineer, Tom Blades, had to look further.

When it came to one particular element needed for the pressure-tolerant motor controllers, a device used to control the speed and torque of the sub’s motor, Blades and his team had to test each component manually.

They found that the quality differed even in parts from the same manufacturer, depending on the factory they came from.

“The manufacturer had no way of differentiating them,” he says.

“We could tell a slight difference in the shade of green.

We had to buy twice as many, manually look at the colour, then put them all though individual testing before we built the circuit boards.”

Another niggle was background noise interrupting communications between Limiting Factor and Pressure Drop.

At 11,000 metres, an audio signal takes seven seconds to travel one way, meaning Vescovo was frequently waiting upwards of 15 seconds for a reply – and that’s without interference.

To demonstrate the problem, Blades pulls out his phone and plays a recording.

Heard loud and clear over the airwaves, instead of Vescovo’s messages, is the hunting sonar of a school of whales.

The solution? Install a filtering circuit, or try again when the oceanic traffic has died down.

“[Designing subs] is great, because there aren’t many people doing it,” Ramsay says.

“Think how many generations cars have been through, everything is so refined.

You sit in a car – any car – and you know where the steering wheel is going to be, you know where the three pedals are going to be, where the gear stick and door handles are going to be.

You don’t have to look.

A sub is totally different; there are no set rules.”

The last hurdle was testing at depth.

To do this, the team travelled to the Krylov State Research Centre in St Petersburg, Russia – the only facility in the world capable of replicating full oceanic pressure – in early 2018.

The pressure hull was placed in the facility’s DK-1000 hydraulic pressure test tank, where it was exposed to pressure in the region of 60,000 tonnes – 1.2 times the pressure at the maximum possible diving depth of the Mariana Trench.

“During testing, the pressure hull was filled with water, with a pipe allowing water to come out as they increased the pressure,” explains Ramsay.

“They do this because if the sub hull imploded during testing, the amount of energy released would be enough to destroy the entire facility.”

The submersible was given a pressure rating of 116.7 megapascals, essentially certifying it to an unlimited diving capacity (a commercial sub might have a rating of 17 megapascals).

Finally, after almost four years of work, Limiting Factor was ready to go.

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

Before the Molloy dive, Vescovo gives a tour of the finished sub.

The pilot’s sphere measures 1.76 cubic metres.

There are two seats, with the viewing portals at knee height.

At chest height, a row of ten spun-carbon-fibre oxygen tanks allow for four days’ oxygen for two people, should the worst happen.

The craft is controlled via a joystick, not unlike a helicopter.

Behind us is an array of switches controlling everything from lights to comms to air temperature.

To help Vescovo get to grips with the sub prior to launch, Lahey built a simulator on which he would practice in his garage in Dallas.

By the time he got into the real vehicle, he knew exactly where everything was, and what the procedures were.

Vescovo’s first action on a descent is to use ballast pumps to make the sub negatively buoyant.

Depending on the depth of the dive, he may then spend up to the next three hours sinking to the ocean floor.

On one dive, he watched the Netflix film Outlaw King on his phone to pass the time, alongside the usual system checks and radio updates with Pressure Drop every 15 minutes.

Around 200 metres from the bottom, Vescovo ejects a series of 5kg weights to become neutrally buoyant and so control the final stage of his descent.

With Limiting Factor safely on the bottom, Vescovo will spend the next two to four hours using the manipulator arm to take rock samples, then travel around the ocean floor, videoing as much biological, geological and cartographical information as he can.

To return to the world above, he ejects a series of 10kg weights, which makes the sub buoyant enough to return to the surface.

Despite his dives lasting up to 12 hours, Vescovo says he never gets claustrophobic: “I like diving solo.” On the Mariana Trench dive, he even took time to use some advice imparted by James Cameron.

“I got my tunafish sandwich, sat back in my chair with my feet up, drinking my Coke, and just looked out the portal,” Vescovo says.

“I was just drifting at the bottom of the ocean, thinking ‘This is so cool’.”

To Vescovo’s surprise, the depths of the ocean were far from empty, eerie deserts.

“The Southern Ocean was a darn grocery store,” he says, describing seeing krill, micro-shrimps, jellyfish and plankton; and, on the Mariana Trench dive, human contamination in the form of a three- to four-inch scrap of either plastic or fabric with a printed "S" on it.

As Vescovo did not retrieve this, he cannot be sure what it was, but he remains adamant that it was not, as widely reported, a carrier bag floating around at 11,000 metres.

Over the course of the expedition, Vescovo has become increasingly interested in science, occasionally carrying out subsequent explorations alongside Alan Jamieson, a marine ecologist at Newcastle University, and Heather Stewart, a marine geologist at the British Geological Survey.

Together, they have found multiple new species of fish, which are analysed in Pressure Drop’s wet and dry labs.

Vescovo says that invisible micro-plastics are “the real, pernicious danger to humankind – the micro and nano-plastics that will get into the very smallest bases of the food chain”.

The mission hasn’t always been plain sailing.

The two most dangerous things that can happen inside a submersible at depth are a leak or a fire.

Either situation is, Vescovo says, “the stuff of nightmares”.

Vescovo and Lahey were on an early test dive in the Bahamas, cruising at about 5,000 metres, when they smelled smoke.

They were two hours from the surface.

“We’d just powered up the manipulator and it must have burned out some insulation in one of the circuit boards,” Vescovo says.

“Patrick and I just looked at each other, both thinking, ‘What do we do?’ We turned off the offending circuit, and thankfully the problem went away.” Although confident the danger had passed, Vescovo and Lahey followed protocol and immediately began their ascent.

“All hell broke loose [in the Pressure Drop control room],” says Rob McCallum, founding partner of EYOS Expeditions, and the man responsible for running the logistical side of the Five Deeps operation.

“It became apparent about halfway through the ascent that it was just a popped fuse.

For a submersible, a fire inside is the worst scenario.

Even a popped fuse in an oxygen-rich environment can be a real problem; look at the Space Shuttle Challenger.” It was an early warning, and exactly what test dives are for.

To Vescovo, it hammered home that, despite rigorous testing, there is always room for error.

“You know the maths, but you do have in the back of your mind, ‘What if it’s wrong?’” he says.

“Even though we tested it, what if there’s something different in the real ocean? You just don’t know.

You’re watching the depth tick down 7,000, 8,000, 9,000 metres, and you know how much pressure is out there.

You’re just hoping you don’t spring a leak or something.”

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

Each dive has presented its own unique problems.

The second voyage, to the Antarctic’s South Sandwich Trench, required a gruelling 30-day journey from Montevideo, Uruguay to Cape Town, South Africa, with a few days allowance for the dive in the middle.

Despite an extra level of caution around icebergs, the dive was successful.

On the Mariana Trench dive, the sheer length of time it took Vescovo to travel 11,000 metres down meant the ship’s crew were often working around the clock.

“There’s no time to rest the crew, or swap them out,” McCallum says.

“After 10 days of doing a deep dive every second day, people are shot.”

But the first dive, in the Atlantic’s Puerto Rico Trench was undoubtedly the most difficult.

“The first dive was different, because it was the final step in a gruelling series of sea trials,” says McCallum.

As the team was preparing to tick off the first dive, the submersible experienced systems failure three days in a row.

“It was our first real test out of a trial situation, and it was ugly.

It got to the point where Victor sat in my office and said: ‘Either it works tomorrow or I’m scrapping the whole thing.’”

On the fourth day, McCallum briefed the team.

“I said: ‘We don’t want miracles, we’re not going to give you a big rah-rah, yay team speech.

But we’ve had four months of practising, you all know what to do, so go out there and do it.

No more, no less.’ And they did.”

There was applause, cheers, hugs and tears when Vescovo radioed to say he had finally made it to the bottom of his first ocean.

“He came up at sunset, you had this big orange sky, and he surfaced right on dusk with the lights on under the water,” McCallum says.

“It was a magic day.”

Ahead of his final Five Deeps dive in the Molloy Deep, Vescovo is feeling confident.

“One can never be complacent diving 5,000-plus metres, but by this point we have refined our launch and recovery procedures, diving protocols, and emergency procedures, and are confident that things will go smoothly,” he says.

Reeve Jolliffe and Enrico Sacchetti

Back in the Arctic Ocean, at 3.34pm – three hours after Vescovo started his descent – word arrives from Limiting Factor that sub and pilot have safely touched down at the bottom of the Molloy Deep.

There are cheers and claps in the control room.

Vescovo and his team have made history.

But there is still the small matter of returning to the surface.

Limiting Factor surfaces 150m away from Pressure Drop, just before 8.40pm.

The ship adjusts its course, launching the Zodiac and a 28ft protector RHIB boat as all hands make ready to receive the submersible, a flat white shape buffeted by the waves.

The swimmer climbs aboard and attaches the safety lines, then Limiting Factor is winched out of the water, up to the back of the mothership's aft main deck in a fluid reverse of the launch some eight hours earlier.

The cockpit opens, and Vescovo’s hand emerges, five fingers splayed: five dives completed.

He may be one of 416 people to have completed the Seven Summits and one of 12 Americans to have climbed the Summits and skied to the two poles – but he has just become the only person in the world to have dived to the bottom of the five oceans.

As he climbs down, the Zodiac lets off flares while the ship blows its horn in celebration.

Vescovo hugs the crew members one by one.

Later, when the initial celebration has died down and he has had time to decompress and shower, he sits alone in the ship’s galley with a large plate of spaghetti and a Diet Coke.

On the walls are vintage film posters for Mystery Submarine and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Surrounded by them, and considering what he has just done, Vescovo is in a reflective mood.

“I don’t know why I want to do this.

Why did Shackleton have a compulsion to go the South Pole?

Some people want to go to the blank spaces on the map, it’s just something deep inside of us,” he says.

“I remember reading Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Islandwhen I was a little kid.

I kept going back and looking at the map.

The scenes of exploration sang to me, and they still resonate with me.

As I grew up I never lost that.

I’m still that kid that always loved looking at maps and going there.”

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment