On a routine passage from Florida to Puerto Rico, a cargo ship sails into the heart of a hurricane.

No one aboard survives.

With the discovery of its black-box recording, we re-create the ship’s final 26 hours and the decisions that sealed its fate.

Photo Illustration by Garrigosa Studio

From Men's journal by Jeff Wise

It started as a dip of low pressure over the Atlantic that gathered a loose circle of sluggish wind.

Ruffled, the summer-warmed sea released more moisture as vapor and the pressure went down a bit further.

The wind picked up, driving big waves and unleashing more moisture and heat.

During the next few days, this chain reaction turned into an atmospheric buzz saw that spanned hundreds of miles: Hurricane Joaquin.

CNN's Martin Savidge details El Faro's journey as the doomed container ship ventured toward Hurricane Joaquin.

Sep. 29, 8:10 p.m.: Left Jacksonville Port. Three hours before El Faro departed, the National Hurricane Center's 5 p.m. advisory expected Joaquin to become a hurricane within 24 hours.

Sep. 29, 11:06 p.m.: Three hours after El Faro departed, the NHC's 11 p.m. advisory said that Joaquin is expected to become a hurricane in the next 12 hours.

Sep. 30, 6:16 a.m.: Begins to veer slightly south from usual course. Travelling at 20.0 knots, near its top speed.

Sep. 30, 2:13 p.m.: Passing northern Bahamas, about 25 miles south of its usual course at 19.9 knots.

Sep. 30, 9:09 p.m.: El Faro continues to veer south west from normal course, now very close to the Bahamas.

Oct. 1, 2:09 a.m.: Slowing to 16.9 knots, the ship is about 90 miles south of its usual course. El Faro is now in the direct path of the storm.

Oct. 1, 3:56 a.m.: Last known location logged. The ship is believed to have sunk after being caught in Joaquin's ferocious winds and high seas.

Alternate route: In August, El Faro used another route which would have avoided Joaquin's path. It is unclear why the ship did not take the other route this time.

Sep. 29, 11:06 p.m.: Three hours after El Faro departed, the NHC's 11 p.m. advisory said that Joaquin is expected to become a hurricane in the next 12 hours.

Sep. 30, 6:16 a.m.: Begins to veer slightly south from usual course. Travelling at 20.0 knots, near its top speed.

Sep. 30, 2:13 p.m.: Passing northern Bahamas, about 25 miles south of its usual course at 19.9 knots.

Sep. 30, 9:09 p.m.: El Faro continues to veer south west from normal course, now very close to the Bahamas.

Oct. 1, 2:09 a.m.: Slowing to 16.9 knots, the ship is about 90 miles south of its usual course. El Faro is now in the direct path of the storm.

Oct. 1, 3:56 a.m.: Last known location logged. The ship is believed to have sunk after being caught in Joaquin's ferocious winds and high seas.

Alternate route: In August, El Faro used another route which would have avoided Joaquin's path. It is unclear why the ship did not take the other route this time.

As the Category 4 storm bore down on the Bahamas with winds peaking at 140 miles an hour, people evacuated and vessels raced for safety.

But one ship did not.

On October 1, 2015, the SS El Faro — a cargo carrier whose veteran 33-member crew enjoyed modern navigation and weather technology — sailed into the raging heart of the storm.

Everyone aboard perished in what ranks as the worst U.S.maritime disaster in three decades.

Investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) were left to grapple with a seemingly unanswerable question: Why?

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board released undersea footage showing the wreck of the cargo ship El Faro, which sank during Hurricane Joaquin in early October, 2015.

Video documentation of the El Faro wreckage and associated debris field from the CURV-21 remotely operated vehicle.

Video documentation of the El Faro wreckage and associated debris field from the CURV-21 remotely operated vehicle.

The NTSB launched one of the most comprehensive inquiries in its 50-year history, interviewing dozens of experts and colleagues, friends, and family members of the crew.

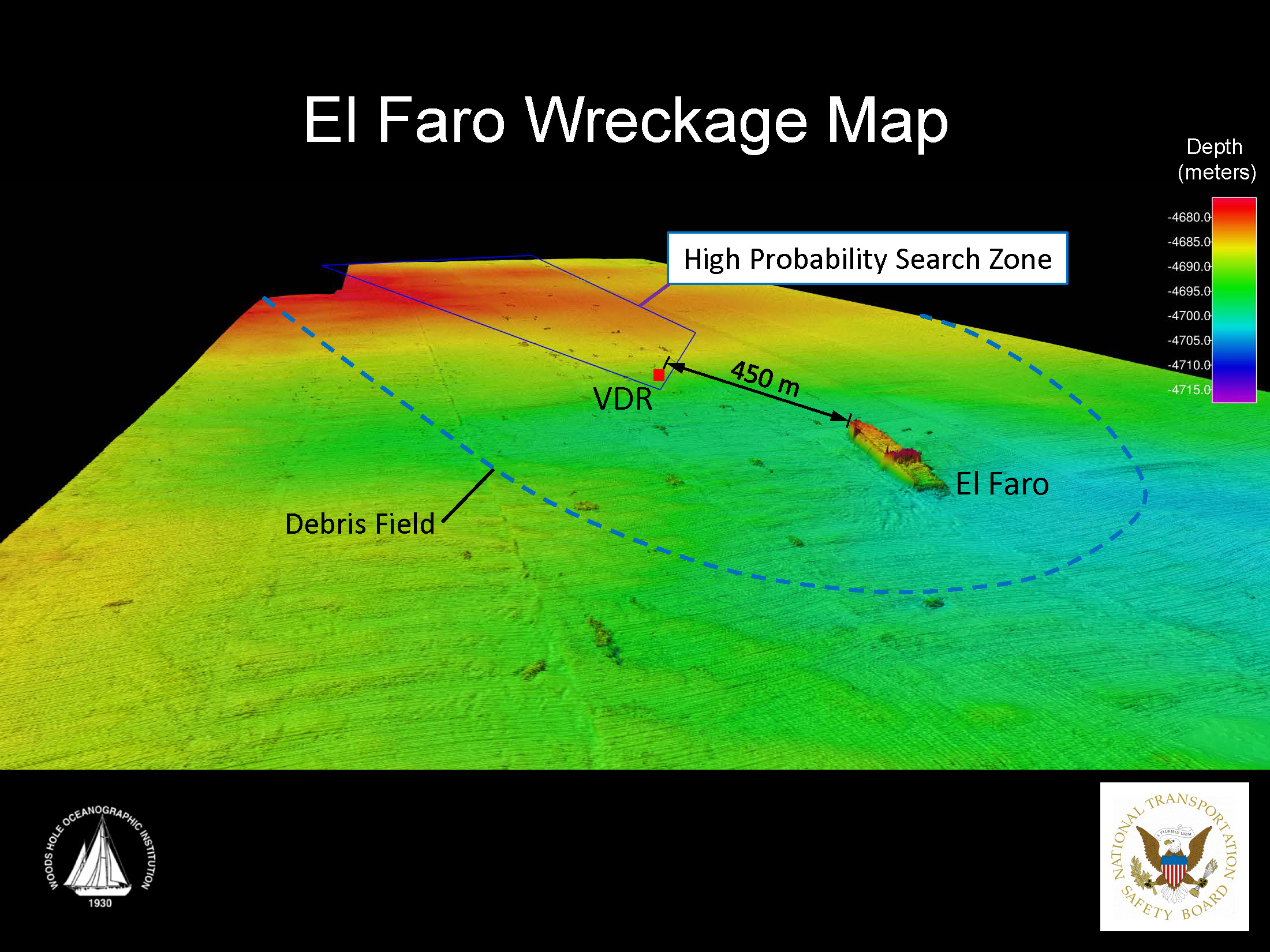

Then, last August, came the crucial discovery: A robot submersible retrieved El Faro’s voyage data recorder from the three-mile-deep seabed.

The black box contained everything that was said on the ship’s bridge, right up to its final moments afloat.

The transcript reveals a narrative that unfolds in almost cinematic detail, with foreshadowing, tension, courage, and hubris.

Like most tragedies, no one factor brought on the disaster — but human error was chief among the problems.

This is the answer to the riddle of El Faro’s baffling final path, in the words of the crew members themselves.

SEPTEMBER 30, 5:36 AM

As the recording begins, El Faro — Spanish for “the lighthouse” — is 150 nautical miles southeast of Jacksonville, Florida, steaming toward San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The sea is calm.

In the predawn darkness, the ship’s captain, 53-year-old Michael Davidson, pores over navigational charts with 51-year-old chief mate Steve Shultz.

El Faro shuttles the weeklong route back and forth between Jacksonville and Puerto Rico roughly four times a month, as regular as a commuter train, carrying cars and containers filled with groceries, clothing, electronics, and other consumer goods.

Today, though, there’s a hiccup.

Tropical Storm Joaquin, which has just been upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane.

The ship can expect 45-mile-an-hour winds and 12 to 15-foot swells — a rough ride even for the 790-foot El Faro.

Hurricane Joaquin is 200 miles northeast of the Bahamas and currently on a course straight for the islands — and El Faro’s track line — but the forecast predicts the storm will soon curve to the northwest.

If they angle their course slightly south, Davidson reasons, they’ll scoot through a gap between the islands and the storm.

This would be only a 10-mile diversion, a distance that means the trip will take just 30 minutes longer and burn a negligible amount of extra fuel.

Still, the decision doesn’t seem to sit well with Davidson.

A 20-year veteran of the U.S.

Merchant Marine, he had applied for a transfer to a newer ship with TOTE Maritime, El Faro’s shipping company.

He may have thought that even a minute amount of extra expense wouldn’t help his cause.

“We’re not that much off course,” Davidson says, as if to reassure himself.

“It’s a good little diversion.

Are you feelin’ comfortable with that, Chief Mate?”

“Yes, sir,” Shultz says and adds, “The other option is drastic.”

That option is a more southerly route called the Old Bahama Channel, which would require the ship to turn 90 degrees to the right, sail 200 miles south, then turn east, and sail along the northern coast of Cuba, sheltered by the islands of the Bahamas.

The ride would be much smoother, but the trip to San Juan would be 160 miles longer — six hours’ sailing time and about $5,000 in extra fuel.

“It doesn’t warrant it,” Davidson says.

“Can’t run from every weather pattern.”

“Not for a 40-knot wind.”

“Now, that would be the action for some guy that’s never been anywhere else.”

The captain mimics a panicky voice: “Oh my God! Oh my God!”

Davidson had endured plenty of rough water, including a decade running oil tankers from the legendarily stormy Gulf of Alaska to the West Coast.

He noted one particular voyage across the Atlantic in the transcript: “We had a gust registered at 102 knots.

It was the roughest storm I had ever been in — ever.”

“It should be fine,” Davidson says, then corrects himself.

“We are gonna be fine, not should be.

We are gonna be fine.”

To the east, the sky is growing bright.

“Oh, look at that red sky over there.

‘Red in the morning, sailors take warning,’ ” Davidson says, quoting the old seafarers’ saw.

“That isbright.”

11:45 AM

The morning opens into a fine tropical day, blue skies with temperatures in the high 80s.

But the swell has started to build with the energy of Joaquin, still some 300 miles away.

At noon, 34-year-old second mate Danielle Randolph begins her shift on the bridge.

Randolph is a popular member of the crew, an extrovert with a passion for pumpkin-spice coffee and a penchant for singing along with the radio.

By now the ship is approaching the first of the Bahamian islands, Little Abaco.

Third mate Jeremie Riehm tells Randolph about the slightly altered course that Davidson has laid out.

As second mate, Randolph is responsible for the ship’s navigation.

She makes clear that she doesn’t think the captain is taking Joaquin seriously enough.

“He’s telling everybody down there, ‘Oh, it’s not a bad storm — it’s not even that windy out.

I’ve seen worse,’ ” she tells Riehm.

Even the amended route El Faro is on exposes it to the risk of getting trapped between the storm and the shallow waters of the Bahamas.

“It’s nothing — it’s nothing!” Randolph says, quoting Davidson.

“I think he’s trying to play it down because he realizes we shouldn’t have come this way.

Saving face.”

Minutes later, Davidson returns to the bridge, complaining that the engine room isn’t giving him as much speed as he’d like.

“Oh yeah?” Randolph asks.

“I think now it’s not a matter of speed.

When we get there, we get there — as long as we arrive in one piece.”

3:45 PM

By the time chief mate Shultz returns for his 4 PM to 8 PM shift, the ocean swell has increased to eight feet, the crests whipped into whitecaps by the stiffening wind.

The deck crew has tightened the lashings that hold El Faro’s 391 containers in place on the deck and scoured the ship to make sure everything has been secured.

El Faro’s sister ship, El Yunque, is 33 miles abeam, heading in the opposite direction toward Jacksonville.

Shultz calls on the radio for a chat.

El Yunque’s chief mate tells him that they put on speed to outrace Joaquin but still got beat up pretty bad.

At one point, they recorded gusts of more than 100 miles an hour.

“You are going the wrong way,” the chief mate says.

When Davidson returns to the bridge, Shultz does not pass along this warning.

“There could be a chance that we could turn around?” asks the helmsman on duty, 49-year-old Frank Hamm.

“Oh, no, no, no,” says Davidson.

“We’re not gonna turn around.”

6:51 PM

As twilight settles, Davidson comes up from his office to find Shultz standing watch.

“I just sent you the latest weather,” Davidson tells him.

Four times a day, the captain receives a forecast from a private meteorological service he subscribes to called Bon Voyage System (BVS).

Its colorful graphics, with areas of severe weather in yellow and dangerous weather in red, are easy to understand, and Davidson relies on the reports exclusively, ignoring the hurricane alerts and National Weather Service (NWS) updates that are printed out and posted on the bridge, and are the standards most captains use.

What Davidson doesn’t know is that the BVS forecasts are up to 21 hours out-of-date, and their estimate of Joaquin’s location is off by as much as 500 miles.

The free NWS reports are timelier and more accurate.

But by now, even the BVS forecast has grown ominous.

It shows the storm continuing on its southern course toward the Bahamas and El Faro.

Davidson plots a new course that will take them around San Salvador Island, which, according to the BVS chart, will provide shelter and limit the size of the swells.

However, the three officers have been watching more accurate forecasts and have a much clearer idea of what’s in store.

All three tell Davidson they’re concerned about the ship’s course, but the captain is unfazed.

Davidson leaves the bridge at 8 PM, just after third mate Riehm relieves Shultz.

“I will definitely be up for the better part of your watch,” Davidson tells Riehm.

“So if you see anything you don’t like, don’t hesitate to give me a shout.”

He heads to his stateroom for the night.

As he leaves, the National Hurricane Center upgrades Joaquin to a Category 2, with winds of 105 miles an hour.

10:30 PM

As the night drags on, the weather gets progressively worse.

Bands of heavy rain and gale-force winds lash the ship as El Faro enters the main body of the storm system, an area of rainfall the size of South Carolina.

In the control room, Randolph continues to worry about their predicament.

If they were in the open ocean and the storm grew dangerous, they could turn tail and run, but as it is, their options are limited, with the ship hemmed in by the islands and reefs to the southwest.

“We don’t have much space,” she tells her helmsman, Larry Davis.

“Not much wiggle room, you know, ’cause it’s so shallow everywhere.”

“I don’t like our chances,” the helmsman says.

At 12:26 AM, the satcom printer, which provides the latest updates from the NWS, chatters to life and spits out a new report.

Randolph tears it off and reads.

Joaquin hasn’t turned, as all the forecasts predicted.

In fact, it’s grown stronger, and they’re heading right into it.

“I may have a solution,” Randolph says.

She shows the helmsman the chart.

Around 2 AM, they’ll pass Rum Cay.

At that point, they can turn south and head for Crooked Island Passage.

They’ll avoid hurricane-force winds, and once through the passage, they’ll be sheltered from the swell by the islands.

“From there we connect with the Old Bahama Channel,” Randolph says.

A weather report comes on the radio: Joaquin has been upgraded to a Category 3 hurricane, with winds of more than 111 miles an hour.

As if on cue, three minutes later, the ship lurches violently to the left, nearly knocking Randolph and the helmsman off their feet.

“Whoa!” the helmsman shouts.

“Biggest one since I’ve been up here.

This is fixing to get interesting.”

“Mistaaake,” Randolph drawls.

Joaquin 1st Oct, 2017 satellite view

courtesy of Weather

OCTOBER 1, 1:20 AM

El Faro approaches Rum Cay.

If Randolph is going to make a turn to the south, she’ll have to do it soon.

“I’m going to give the captain a call,” she says.

When Davidson finally picks up, it’s clear he’s been asleep.

“It isn’t looking good,” Randolph tells him, then explains her idea.

Davidson isn’t convinced.

He tells her the worst of the storm will soon be behind them, so she should stay on course.

She hangs up and turns to the helmsman.

“He said to run it.”

At this point, Randolph has a choice.

Her captain has given her an order that she knows could have a terrible outcome.

She can follow it, putting her crew mates in certain danger, or she can take matters into her own hands and turn the ship toward a hope of safety.

Going rogue, though, is not an option for Danielle Randolph.

To defy Davidson’s order is the kind of insubordination that would get her fired upon arrival in San Juan.

The chain of command has ruled life at sea for centuries, and for good reason: A crew’s safety is dependent on discipline, with no room for dissension.

A captain’s unquestioned authority is something a mariner accepts with the job.

So, instead of turning south, Randolph instructs the helmsman to continue east.

Directly into the storm.

1:55 AM

A particularly large wave slams into the ship.

“That was a good one,” Randolph says.

“Definitely lost some speed.

Although we’re not doing the max RPMs.”

The ship’s engine burns oil to generate steam, which drives the turbine that turns the propeller.

It’s technology that was familiar to sailors during Titanic’s era.

If the boiler can’t generate enough heat, the propeller’s revolutions per minute will fall and the ship will slow.

The 40-year-old El Faro had reportedly suffered loss of propulsion at sea before, and its boilers were scheduled to be repaired later that fall.

A little-known quirk of the powerplant design was that if the ship listed, or leaned over, more than 15 degrees — an unlikely possibility — the lubricating oil would run to one side and the engine would stop.

It’s a problem that is less likely to occur on modern ships.

“Damn sure don’t want to lose the plant,” the helmsman says, referring to El Faro’s engine.

That’s because a ship is designed to plunge through heavy weather bow first.

But with insufficient power, wind and swell will cause it to list sideways, exposing a vulnerable flank.

Soon the ship could take on and fill with water, then capsize.

El Faro ship

2:44 AM

Over the next hour, Joaquin batters the ship with increasing intensity.

Waves break over the bow, sending torrents of water surging over the deck.

Explosions of spray splatter the windows of the bridge.

Unseen clankings reverberate over the howling of the wind as the storm wrenches away loose fittings.

“Figured the captain would be up here,” says the helmsman.

“I thought so, too,” says Randolph.

“He’ll play hero tomorrow,” the helmsman says.

A few minutes later, a massive wave hits.

“That was a doozy,” Randolph says, nervously laughing.

“We won’t be able to take more of those.”

Minutes later another wave hits, and this one nearly knocks Randolph off her feet.

An electronic alarm sounds, warning that the ship’s autopilot has been shoved off course by the force of waves that have grown too big for it to handle.

4:09 AM

Shultz arrives on the bridge and relieves Randolph, who goes below deck and staggers to her cabin.

There she writes an email to her mother: “We are heading straight for the hurricane. Give my love to everyone.”

On the bridge, Davidson returns after an eight-hour absence.

The winds raking the ship are 100-plus miles per hour, but Davidson feigns nonchalance.

“There’s nothing bad about this ride,” he says.

When Shultz asks if he’s managed to get any sleep, he says he’s been “sleeping like a baby.”

“Not me,” Shultz says.

“What? Who’s not sleepin’ good? How come?”

“I didn’t like it.”

“Well, this is every day in Alaska,” Davidson retorts.

Shultz points out that the ship is listing to the right.

The wind is hitting El Faro’s exposed left f lank, pushing it even further to the right side.

“Yeah,” the captain says.

“The only way to do a counter on this is to fill the portside ramp tank up.”

In other words, they can pump stored water from the right side to the left side of the ship, to help steady it against the wind.

If they don’t, the list will continue and the powerplant could fail.

While Davidson goes to get breakfast, the chief engineer phones to tell Shultz that the engine lubricating oil is acting up.

Evidently, shifting the water hasn’t worked.

It’s time for plan B: Turn El Faro into the wind.

Davidson rushes back to the bridge.

“Going to steer right up into it,” he declares.

“Let’s put it in hand-steering.”

To prevent a more drastic list, they need to point the bow directly into the hurricane-force wind.

But that’s no easy feat.

El Faro is now in the eye wall of a hurricane that is strengthening from Category 3 to Category 4.

Thirty-foot waves, their crests whipped to foam by 115-mile-an-hour winds, hammer the ship every 10 seconds.

The wind howling against the bridge sounds like a jet engine on takeoff.

courtesy of Reuters

5:43 AM

“We got a prrroooblem,” Davidson says.

Engineering has called with more bad news.

A type of hatch called a scuttle, located between cargo decks, has flown open, allowing water to flood the hull of the ship.

A lot of water sloshing in an open hold makes a ship incredibly unstable and prone to capsizing.

Efforts to seal the hatch fail, so Davidson orders the crew to run water pumps to remove the seawater.

He tells Shultz to go check it out.

The chief engineer calls in soon after.

“OK,” Davidson tells him, “I’m going to turn the ship and get the wind on the starboard side.

Give us a port list.” Davidson hopes that with the ship leaning in the other direction, the water will drain away and they can secure the hatch.

Sensing that the ship is in trouble, Randolph returns to the bridge in her off-duty clothes.

Davidson greets her with a friendly “Hi!” and tells her about the hatch.

A few minutes later, Randolph notices that the engine power is falling and asks, “Did we come down on the RPM, or did they do that?” referring to the engine room.

Davidson says he didn’t ask them to reduce power.

It’s more than worrying.

A loud thump comes from outside.

“There goes the lawn furniture,” says Randolph, likely seeing objects on the deck start to come untethered.

“I’m not liking this list,” Davidson says.

A few seconds later, the engine RPMs drop.

He turns to Randolph: “I think we just lost the plant.”

6:55 AM

By now the goal is no longer to get to San Juan but to simply keep the ship afloat.

With each swell, El Faro lurches further onto its right side.

“How long we supposed to be in this storm?” Hamm asks.

“Should get better all the time,” Davidson says.

“We’re on the back side of it.”

Davidson makes a satellite phone call to Capt.

John Lawrence, the head of TOTE’s emergency response team and the man responsible for coordinating rescue efforts.

Instead of abandoning El Faro, Davidson tells him, “No one’s panicking.

Everybody’s been made aware.

Our safest bet is to stay with the ship.

The weather is ferocious out here.”

After he hangs up, Davidson tells Randolph to send a satellite distress signal.

“Roger.” The satellite terminal chirps: Message sent.

The time is 7:13 AM.

“All hell’s gonna break loose,” Davidson says.

Somewhere, alarm bells are ringing and rescue teams are saddling up.

“Wake everybody up!” Davidson shouts.

“Wake ’em up!” He adds: “We’re going to be good.

We’re going to make it.”

Shultz hurries back to the bridge.

“I think that water level’s rising, Captain.”

But he can’t determine where the water is f looding in.

“I saw cars bobbing around.”

“All right, we’re going to ring the general alarm here and wake everybody up,” Davidson says.

“We’re definitely not in good shape right now.”

Davidson tells Shultz to “muster all the mates,” then calls the engine room: “Captain here.

Just want to let you know I am going to ring the general alarm .

We’re not going to abandon ship or anything just yet.

All right? We’re gonna stay with it.”

Davidson hangs up, turns to the crew on the bridge, and shouts, “Ring it!”

A series of high-pitch tones blare throughout the ship.

7:28 AM

Shultz calls in on a walkie-talkie to report that everybody has mustered on the starboard side.

“Captain, you getting ready to abandon ship?”

“Yeah, what I’d like to make sure is everybody has their immersion suits, and get a good head count.”

A minute later, Randolph lets out a yell.

“I got containers in the water!”

Ravaged by the 115-mile-an-hour wind and bashed by crashing waves, stacks of containers on the deck have started to plunge into the ocean.

The ship is coming apart.

“Ring the abandon ship,” Davidson orders.

A high-frequency bell tone rings in seven short pulses, followed by a long pulse.

“Tell them we’re going in,” says Davidson loudly.

Randolph asks if she can get her life vest.

Davidson says yes and asks her to bring his and one for helmsman Hamm.

“I need them, too!” Hamm yells.

“Please!”

“OK, buddy, relax,” Davidson says.

“Go ahead, Second Mate.”

Randolph leaves, and the captain and the helmsman are alone on the bridge.

The ship is taking on water fast.

The morning light is strong enough now that, through the rain and spray, Davidson can see the front of the ship slip beneath the roiling surface.

“Bow is down,” Davidson says.

“Bow is down!”

He calls Shultz on the radio: “Chief Mate, Chief Mate.”

“Hey, Captain!” Shultz shouts over the freight-train roar of the storm.

“Get into your rafts!” the captain yells.

“Throw all your rafts into the water.”

“Throw the rafts in the water.

Roger.”

“Everybody get off!” Davidson shouts.

“Get off the ship.

Stay together!”

On the bridge, Hamm has slipped on the now steeply pitched deck and is having trouble climbing up.

Each time the ship lurches, the slope gets steeper.

“Cap ... Cap,” he’s saying.

“What? Come on, Hamm. Gotta move. You gotta get up. You gotta snap out of it.”

“OK,” Hamm says.

“Help me.”

“You gotta get to safety, Hamm,” Davidson pleads.

Hamm is becoming increasingly panicked.

“You’re going to leave me.”

“I’m not leaving you! Let’s go!”

Hamm lets out a primal scream.

“I need somebody to help me! You don’t want to help me?”

“I’m the only one here, Hamm.”

“I can’t!” Hamm yells.

“I’m a goner.”

“No, you’re not!” Davidson shouts.

Hamm screams as the deck lurches ever steeper.

The voices cut out.

7:39 AM

Thousands of tons of water crash onto El Faro’s exposed left flank.

Destabilized by flooding below decks, the ship eases past the critical angle.

The deck rises up to vertical, then past it, and like a toppled seven-story building, it breaks apart.

Containers stacked on the fore and aft decks scatter like Jenga blocks as seawater surges into the shattered hull.

The crew members mustered below are unable to launch the lifeboats.

Even if they could, the open-top boats would likely capsize almost immediately.

The life jackets and immersion suits are likewise useless.

Simply put, trying to abandon El Faro in the teeth of a Category 4 hurricane is suicide, and the crew doubtless knew it.

A hundred feet beneath the roiling waves, where the morning light fades into perpetual black, the sea is calm.

Torn-off sections of the ship ride downward toward it, streaming bubbles, followed by a torrent of man-made objects: containers, cars, air conditioners.

They fall three miles down, into the quiet.

Courtesy NBCMiami / NTSB

The Aftermath

The Coast Guard in Portsmouth, Virginia, picks up El Faro’s emergency signal.

They spend a day trying to radio the ship.

Days later, once the storm has subsided, they send an HC-130 reconnaissance plane from Clearwater, Florida.

It spots nothing.

When Danielle Randolph’s mother, Laurie Bobillot, opens the last email that her daughter sent her, she immediately fears the worst.

The sign-off — “Give my love to everyone” — sounds like a farewell.

Three days after the sinking, a Coast Guard helicopter sees a body floating in an immersion suit but is unable to retrieve it.

No other remains are ever found.

from NTSB

The immediate reaction was to question the judgment of Michael Davidson.

“I don’t think he believed he was going to get into 100-knot winds, even though the data was right there in front of him,” says Seattle-based ship captain George Collazo, who has done research on the causes of maritime disasters.

“You do something so many times and it always comes out right — you start to get a feeling of invulnerability.”

However, Collazo adds, in the shipping industry, a captain’s job is defined not simply by getting from point A to point B, but by how well he leads and listens to his crew.

By spring 2017, all of El Faro crew’s next of kin had settled claims against TOTE for $500,000 each in pain and suffering and undisclosed amounts for financial loss.

Insurers paid TOTE $36 million for the ship’s loss.

Last May, those insurers launched a lawsuit against StormGeo, the company that owns Bon Voyage System, claiming that its outdated reports were to blame for the disaster.

Apart from settling accounts, anger remains.

“The laws need to be changed,” says Kurt Bruer, a seaman who had worked on El Faro.

“The industry is more interested in protecting the Jones Act [the law that requires that only U.S. ships sail to and from U.S. ports] than they are about safety.

They don’t care about us mariners — we’re just replaceable bodies.”

NTSB releases additional video documentation on last year's efforts to locate and recover the El Faro voyage data recorder.

(Both TOTE and StormGeo, citing the unfinished investigation, declined comment for this story.) Even if the NTSB proposes new regulations, there will be powerful industry resistance to any money-spending measures.

Mandating closed lifeboats for older ships, for instance, would be opposed strongly by ship owners as being overly expensive, says Robert Markle, a marine safety consultant for the Coast Guard.

“This whole tragedy has opened my eyes so much,” says Bobillot.

She reels off a litany of safety shortcomings aboard El Faro, from a shortage of emergency locator beacons to the lack of closed lifeboats.

“Had I known half of what I know now, I would have totally discouraged Danielle from shipping out,” she says.

Then she laughs ruefully.

“I don’t know if she would have listened to her mother.”

Links :

- YouTube : NTSB releases audio transcripts from El Faro

- Jacksonville : Storm track received by El Faro the day before sinking was 21 hours old

- Pulse : Modern Day Ship Weather Prediction Systems and Services

- EurekAlert : Rogue wave analysis supports investigation of the El Faro sinking

- Men's journal : Why the SS El Faro Capsized / The Crew that Tried to Save the SS El Faro

- GQ : Into the Storm: The True Story of a Harrowing Ocean Rescue

- GeoGarage blog : It’s extremely rare for large ships like El Faro to disappear

- GCaptain : USCG El Faro Investigation Report / Coast Guard Releases El Faro Investigation Report: Here’s the Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

Maritime Executive : Coast Guard Releases Final Report on El Faro Tragedy

ReplyDeleteNTSB : Executive summary, including 81 findings, 53 recommendation and the probable cause of the Oct. 2015 sinking of the cargo ship El Faro.

ReplyDeleteMaritime Executive : NTSB Releases its Final Report on the El Faro Tragedy

ReplyDeleteThe National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued a16-page illustrated digest summarizing the critical events and decisions that led to the Oct. 1, 2015, sinking of El Faro and the loss of all 33 crewmembers. The digest also synopsizes the more than 60 recommendations issued throughout the NTSB's investigation of the sinking. The infographics and summary make for an easy-to-read digest, compared with the thousands of pages that comprise the NTSB's final report and associated investigative documents, while still imparting potentially lifesaving information to our stakeholders. While the full accident report, available at www.ntsb.gov, remains the agency's definitive document on our investigation of the sinking, this digest provides an overview of this landmark marine accident, and a review of what government and industry can do to prevent such an accident from happening again. (5/24/18)

ReplyDeleteNTSB video details the investigation of the sinking of US cargo vessel El Faro

ReplyDeleteSafety4Sea : USCG: Lessons learned from El Faro tragedy

ReplyDeleteNTSB final report

ReplyDeleteNTSB video :Sinking of US Cargo Vessel SS El Faro