From BBC by Richard Fisher

Weird and wonderful objects washed up on the world's beaches shed more light on the workings of the ocean currents than you might think.

Marooned on an island, if you threw a message-in-a-bottle into the ocean, would you be saved?

The answer, according to researchers, depends on where you are.

An interactive map shows how floating objects dropped into the ocean travel over the years.

So drop a bottle off the east coast of the US, for example, and if you’re lucky, it may have reached France, Spain or North Africa after a couple of years – but equally it could have turned around and been trapped in an ocean gyre circling around the centre of the Atlantic.

Objects can flow around the ocean for years or even decades before they reach shore.

In April, a message-in-a-bottle turned up off the coast of Norway after a staggering 101 years at sea.

Decade-plus journeys aren’t unusual.

On New York beaches, for instance, passers-by have reported finding treasure that appears to have been away from land for years, including unusual animal bones, dentures and even a robot hand.

And this week BBC Magazine reported on how tiny pieces of Lego have been continually washing up on the shores of Cornwall in the UK since 1997.

These strange objects enter the sea via beach litter, rivers and

shipping containers lost overboard.

Not only do they provide a curious

and occasionally disturbing record of humanity’s effects in this era,

they can also provide researchers with surprising insights into the vast

ocean currents that sweep the globe.

A 2014 survey by the World Shipping Council suggests around 2,683 containers were lost at sea per year between 2011 and 2013.

The real figure could well be more, as many go unreported and no single database keeps track.

Perhaps

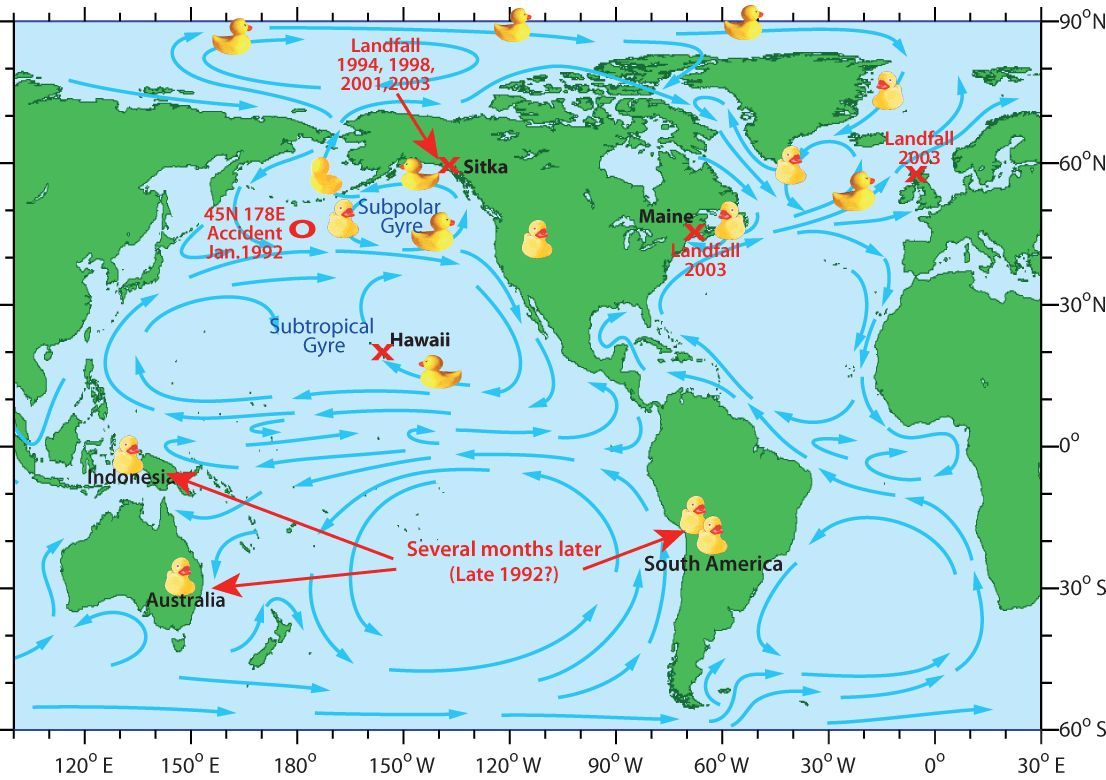

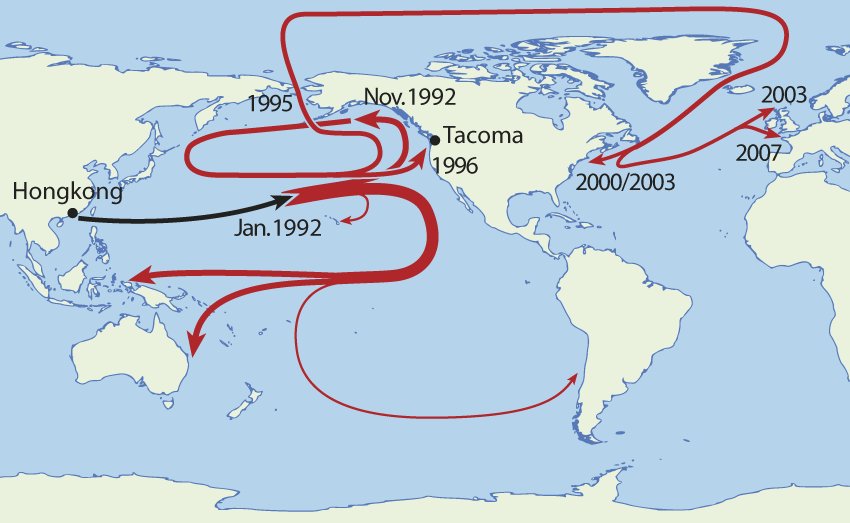

the most famous case of drifting ephemera was a fleet of more than

28,000 rubber ducks and other bath toys, known as the Friendly Floatees.

The ducks accidentally fell into the Pacific from a container ship en

route from China to Seattle in 1992, and were tracked by the

oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmayer, who called on beachcombers to report sightings.

The Floatees spent over a decade circling on the sea.

What was perhaps

most striking was just how far the ducks travelled, with some ending up

in Europe and Hawaii, and confirmed sightings continued until at least

the mid-2000s.

(See the path the rubber ducks took here.)

This hinted that floating objects take a much longer journey between oceans than previously realized.

In 1992, around 29000 rubber ducks fell off a cargo ship in the Pacific Ocean.

This is where they made landfall.

In 2012, Erik van Sebille of the University of New South Wales in Australia and colleagues confirmed this suspicion by using a network of around 20,000 satellite-tracked ‘drifter’ buoys.

They found that there are six major patches of plastic garbage in the oceans: five in the subtropical seas, and one more high up in the Arctic Barents Sea that was previously unknown.

And crucially, this work revealed how the plastic migrates between the patches over long timescales.

“They are much more connected than ever envisioned,” he says.

“They leak.”

This research inspired them to create their interactive map.

According to van Sebille, in some regions of the North Pacific there's potentially more weight in plastic than there is in life.

A lot is too buoyant to sink. “It’s almost like the turd that won’t flush,” he laughs.

Contrary to popular belief, however, the stuff does not exist as giant islands.

It is dispersed and much of it is ‘microplastic’ – tiny, eroded fragments – and so it’d be near-impossible to go out there and sweep it up.

The danger to wildlife is clear.

Since most of this circulating material does not decompose easily, eventually it may even wind up in the rock record, deposited on beaches or in the deep ocean inside fish poo after they have digested it.

Indeed, US researchers recently described a new type of solid rock found in Hawaii containing plastic bags, rope and bottle tops.

They called it “plastiglomerate”.

Peer closer, and they might even get lucky and find whole objects, such a Barbie arm, a pair of dentures – or even a message-in-a-bottle.

Links :

- io9 : Track the path of any object drifting on the ocean

- BBC : The Cornish beaches where Lego keeps washing up

- The Telegraph : Millions of tiny Lego pieces lost at sea more than 17 years ago are still washing up on Cornish beaches

- GeoGarage blog : It's amazing what a duck can teach you

No comments:

Post a Comment