Remote work.

Antarctica style by satellite phone.

Circa 2001 Courtesy of Peter Lane Taylor

Antarctica style by satellite phone.

Circa 2001 Courtesy of Peter Lane Taylor

From Forbes by Peter Lane Taylor

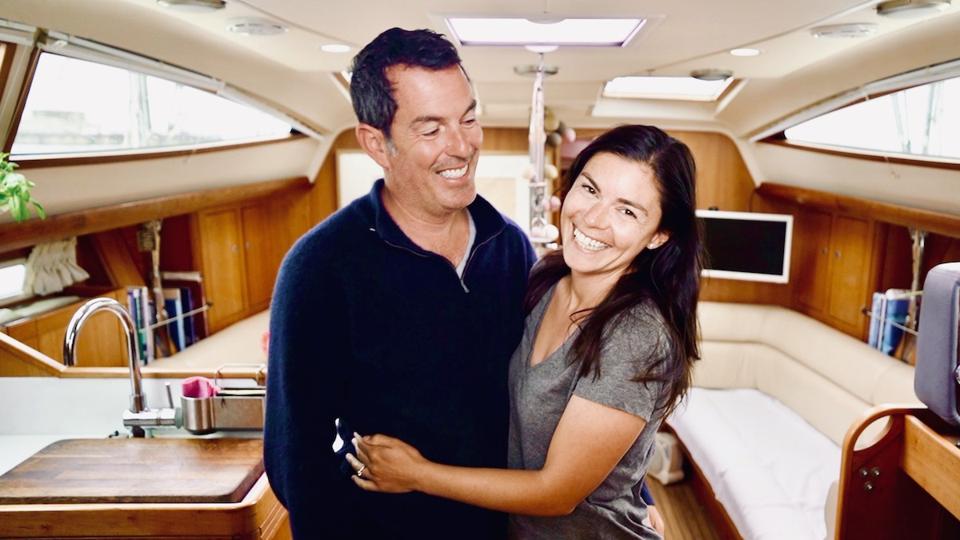

Nick Fabbri and Terysa Vanderloo—the former a 49 year-old dentist from the U.K. and the latter a 35 year-old Australian paramedic who’d met a decade earlier in India—can vividly remember the day that COVID-19 shut the world down.

Fabbri was onboard the couple’s 38’ sailing yacht Ruby Rose in a marina on France’s Atlantic coast, completing routine winter maintenance work.

Vanderloo was back in Adelaide, Australia, visiting with her mother and sister.

When reports hit their morning news feeds that borders around the world were about to lock down, Vanderloo flew immediately back to London, where Fabbri’s family lived.

The next day, Fabbri snagged one of the last trains back across the English Channel.

For the next three months the couple quarantined in London as the global economy shut down before France re-opened its borders to non-residents so that they could get back to Ruby Rose in late May.

“That was one of the strangest periods of our lives,” recalls Vanderloo.

“For years, everyone thought that we were crazy to give up our lives to move onto a sailboat and work remotely.

Then all of a sudden there was no place that everyone else wanted to be than isolating and working remotely on a boat.”

Two decades earlier, in late 2001, I experienced something similar to Fabbri and Vanderloo.

On the December day that U.S. and Coalition forces invaded Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, I was on an 8 knot broad reach over a place called “Point Nemo” (reputedly named after the famous submariner from Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea) on a 44’ steel ketch sailing from New Zealand to Argentina across the Southern Ocean ultimately en route to Antarctica.

There is no place that you can get farther from land on earth than here—precisely 1,670 miles from the Pitcairn Islands to the north, the Easter Islands to the northeast, and Maher Island (part of Antarctica) to the south.

Being in the middle of the ocean as it is, there’s nothing particularly remarkable about Point Nemo—no peak, no prayer flag, no welcome center—just a set of GPS coordinates on a screen (48°52.6′S, 123°23.6′W to be exact) to remind you that the nearest shipping lane is so far away that if your boat flounders your odds of survival are basically zero.

At first, it was hard to process the reality that the world was about to go to war from so far away.

Yet, ultimately it became impossible not to obsess over the news every minute of the day because there’s nothing else to do in the middle of nowhere.

Doing deals and running a start-up from here doesn't seem so crazy after all does it?

Getty

The irony of all of this two decades later is that the whole concept of living full-time on a sailboat, working remotely from some absurdly yet remotely beautiful place on earth, and staying connected to the world in a wetsuit from the waist down all of a sudden now seems so predictably, “Of course you can”, instead of “You do what?! From where?!”.

Thanks to a global pandemic that no one foresaw—from tech titans in Aspen gondola-Zooming with investors to PR consultants who’ve decided that there’s no better time to sail around the world—work’s new remote normal is here.

And it’s spectacular.

“I usually wake up with the sun shining through our hatch around 7:30 am,” 40-year old Erin Carey tells me of her typical workday, emailing from her 1984 Moody 47’ sailing yacht Roam, currently wintered up in a marina in the Azores Islands 800 miles west of Spain in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Carey, her husband David, 38, and three children have been sailing around the world for four years now.

Roam, in addition to the family’s now permanent home, also doubles as Carey’s remote office for her global PR firm, Roam Generation, which she’s been running digitally pre-pandemic since 2018.

When I finally catch up with her, it’s not so much a sense of vindication that I get from her on COVID’s unleashing a new wave of remote, mobile workers.

It’s more the satisfaction of inevitability.

“We get ready for the day just like we used to on land,” says Carey.

“After breakfast, I apply makeup if I have a Zoom meeting and put on neat clothes, not sweats, so I feel like I’m at work.

I’m usually in the ‘office’ from 8:30 am to 3 pm in the aft cabin which gives me privacy while Dave is homeschooling the kids and working on the boat.

Pre-pandemic this schedule all seemed so strange to everyone.

Now all of a sudden it’s everyone’s new normal.”

Work’s new remote permissibility since the pandemic began already has re-shaped everything, including crushing the commercial office space sectors in cities like New York and San Francisco and making billions of dollars of new public transit already obsolete.

Yet, when it comes to the hidden white-collar, underworld that’s always dreamed of ditching the office and working remotely, the pandemic has forced an existential labor market question thousands of employers never wanted to address because that would risk validating the very premise of it for millions of potential workers: What if I moved 3,000 miles away and did the same amazing job I do now? Would you have a problem with that?

All of which raises a more practical, still-to-be-proven question: when it comes to “offshore” talent, is there now any such thing as an office too far?

In practice, the simple answer lies almost entirely with technology rather than some kind of woke work culture revolution.

I moved aboard my first sailboat and started working remotely in Key West, Florida in 1994.

Back then, the mobile “stack” available to people like me wasn’t particularly empowering.

The 8” Motorola flip phone I connected to my NEC laptop running Earthlink webmail took 28 minutes to successfully upload my first test email from my cockpit, all while angling the phone towards the cell tower as the boat shifted at anchor.

By 2001, when I sailed over Point Nemo to Antarctica, we’d upgraded to a satellite phone that patched into a 12-pound Toshiba laptop which could send and receive three to four sentence messages at $3.00/minute from anywhere in the world.

Photos and videos? Forget about it.

Phone calls? $6.00/minute.

My wife and I still joke that it was the $7,000 satellite phone bill that kept us together to this day.

But we made it work, hacks and all.

And, more importantly at the time, the whole concept intrigued everyone from editors and readers to film producers to corporate sponsors.

Who works from the middle of nowhere?

Well, back then, a lot of people you never knew about.

But now, post COVID-19, just about everyone else whose employer will give them the greenlight to do so because the technological barriers to entry are more democratized than ever.

Home office redefined and fully connected on the sailing yacht Roam

Courtesy of Erin Carey/Roam

For today’s untethered entrepreneurs like Carey, today’s mobile stack gets smaller, faster, more durable, and more reliable every year.

Carey’s core kit in Roam’s aft cabin includes a 16-inch Macbook Pro with a wireless mouse and keyboard, a 24” pivoting wall mounted monitor for dual screen viewing, iPhone 12 Pro, Ipad Pro, Airpod Pros, and an Apple watch.

Once Carey and her husband arrive in a new country, they buy 2-3 SIM cards for their phones with as much data as possible and then use them as hotspots for 24/7 internet access.

“We put one of those SIM cards into a Digital Yacht 4G Pro Connect 3G/4G Router installed on our boat which utilizes the latest MIMO technology with dual external antennas for fast, long range access that also incorporates a full function Wifi router so multiple devices can connect wirelessly at once,” says Carey.

“We’re also wired with LAN and WAN ports for connection to high power WiFi devices or satellite modems.”

As far as the remote office is concerned, Carey’s work life coalesces around a cloud of Google Docs, Google Sheets, FreshBooks, Apple Mail, Mailbutler (to track emails), Zoom, iCal, WhatsApp and Messenger, FreshBooks for accounting, Canva, Later, and Dropbox to run a collaborative ship that her entire team can access globally anytime, anywhere.

Her growing staff is also increasingly deconstructed and virtual.

“I have an assistant in Australia, a freelance writer in America, a social media assistant who also lives on a boat, and a team of freelance PR professionals who I’ve never met in person,” says Carey.

“Yet, I’m still able to run my business and no one would know the difference unless I told them.

When I’m sailing across an ocean, which is actually very infrequently, we also have a satellite phone to receive text messages and an SSB (single sideband) radio on our boat that can download emails and my team holds down the reins until I get to where I'm going.”

Fabbri and Vanderloo hard are work aboard Ruby Rose

Terysa Vanderloo holding down the office helming Ruby Rose

Courtesy of Ryby Rose

Carey and her husband David’s cord-cutting decision to work remotely and pre-wire their life to function anywhere before COVID hit—while seemingly prescient now—isn’t actually anything new.

It was around the same time prior to COVID’s outbreak that Fabbri and Vanderloo also quit their jobs to sail around the world.

Along the way they decided to film their adventure for family and friends.

That, in turn, grew into a successful YouTube channel as they sailed Ruby Rose across oceans to exotic locations.

It’s now one of the most popular sailing channels on the platform.

“In 2017 we were running out of money and also wanting a creative outlet so we decided to start our own YouTube channel,” recalls Vanderloo.

“And what started as a hobby turned into a full-time business.

We're now able to financially support ourselves entirely with our YouTube earnings.”

As a result, Fabbri and Vanderloo have a little more hardware and software running under the hood to stay literally and metaphorically afloat.

“We now film and produce sailing and boat life videos for a living,” explains Vanderloo, “So the amount of gear—including cameras, audio equipment, drones, and accessories—that we require for that is significant.

When something breaks, we can't just get it replaced with next day delivery like most people.

So we have two of every item that we rely on most while trying to stick to the necessities and not have any superfluous equipment.

That minimalist mentality is part of living on a boat and working remotely anyways.

But it still stacks up when you're doing what we’re doing content wise.”

After 5 years of living onboard, sailing 25,000 nautical miles, crossing 2 oceans and living on three continents, this is the end.

This week we finally sail Ruby Rose across the English Channel and home to the UK in order to sell her to her new owners.

This is our penultimate sail and our last big crossing- and there's a bit of everything!

Join us for our final 100nm passage through the Aldernay Race, across the shipping lanes of the English Channel and to the Solent.

Our life as a sailing couple is almost at the end of this chapter.

The editing suite aboard Ruby Rose

Courtesy of Ryby Rose

Not surprisingly, Fabbri and Vanderloo’s biggest technological bottlenecks—like the Careys’—are no different than every other remote worker’s: power generation, battery life, and access to smoking hot high-speed internet access.

“Part of living on a boat is having a limited power supply,” Vanderloo tells me of the couple’s constant electricity battles, “The amount of charging leads and battery packs that we have for our cameras is crazy.

Then there’s all of the gear we need to do the editing and publishing—our laptops, external SSDs, voice over microphones and headphones.

In order to do our digital marketing and stay active on our socials, we also rely heavily on our tablets, phones and smart watches.

We use solar power to generate electricity and frequently we simply don't have the power to work.

Sometimes we also actually have to make water, run the lights, and operate the boat.”

Staying connected afloat can sometimes be even harder than having the power to do so.

“Connectivity is still our biggest challenge working off the grid,” adds Vanderloo.

“This is improving with every year as internet becomes cheaper and faster.

But we still rely on local SIM cards and tethering off our phones for 4G internet, and the signal can often be weak or patchy.

We also have to wait until we're somewhere with fast WiFi before backing up our raw footage to the cloud or doing major software updates, which means we need to create extra backups on external hard drives.

When we're in countries with poor internet infrastructure, finding internet that's fast enough to upload a video and schedule our social media posts is also a major issue.

Living remotely, especially on a boat, is full of challenges and most of them revolve around the most basic issues of connectivity.”

Working remotely particularly on a boat isn't all sunsets and rum drinks.

"Everything always breaks," says Carey

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

"Everything always breaks," says Carey

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

For Carey and her husband, staying connected while living and working untethered was also their first, biggest hack to sort out.

Living on a boat or in a van or constantly moving around means that you don’t have a fixed address, which means that you often can’t receive Amazon deliveries or shop online.

It also means that if we lose our bank card or our driver’s license expires, it can be a disaster.

But over time we’ve figured it out—especially the business side.

My clients have always been located all over the world, so we’ve always communicated via email and Zoom, signed contracts via Docusign and sent funds via Wise (was TransferWise), Stripe, or Paypal.

At this point, there’s not much we can’t do even in the middle of nowhere.”

The other biggest challenge of working remotely—particularly on a boat—are physics and entropy, says Carey.

Simply put, shit breaks.

“There’s a saying that ‘BOAT’ stands for ‘Bring Out Another Thousand’.

And I’d say that's pretty accurate.

The endless breakages and the insurmountable amount of work that is involved with living on a boat and travelling full time can be extremely challenging.”

When the things that break are also your laptops and wireless routers that keep your remote businesses tethered to the outside world, that can be doubly catastrophic, adds Vanderloo, whose YouTube channel is based on delivering subscribers (and sponsors) regular content when they expect it (i.e., the customers).

“We've had more things than we can remember lost overboard.

I once left a hatch open and it rained, soaking my laptop and rendering it useless.

I couldn't just pop into Apple and get it fixed so I had to wait, unable to do any work, for weeks before finding a computer repair store.

We also recently lost our best microphone overboard as we were sailing, so we had to do a ‘man overboard’ drill to get the microphone back.

But it was good practice!”

I'm the guy on the far right.

Yes we all crammed into that tent.

Antarctica Peninsula circa 2001

Courtesy of Peter Lane Taylor

When I returned from sailing to Antarctica after 8 months living aboard, the biggest challenge I realized I had endured was learning to live with six other people in under 44’—which, during the pandemic, has similarly tested virtually every family and couple in America to the breaking point over the past year that’s been confined at home, most of them for the first time ever.

For those toying with uprooting, working remotely, and embracing romantic #yachtlife and #vanlife tags more permanently, these aren’t minor, aberrant concerns.

“Separation and privacy is still our biggest challenge,” Fabbri and Vanderloo tell me.

“And everyone during the pandemic lock downs has learned the same thing.

On a boat you barely have enough personal space, let alone workspace.

We’ve had burnout from this in the past because we haven’t been unable to create the right boundaries, and so we now have very firm rules: we only do computer work during office hours, and we finish by 5 p.m.

every day so we can enjoy our evenings together.

We don't have a dedicated office or work area, and so we set up our laptops and editing gear every day, then pack everything away in the evening.”

For Carey, who’s running an international PR agency around the clock while simultaneously raising three children and living aboard, the key also is creating artificial boundaries that work around her lifestyle and job both in time as well as space.

“Running a PR business with clients all over the world means that I go to sleep when the other half of the world is waking up,” says Carey.

“Which means that my workday can be really long if I’m not careful to switch off.

At the same time, the lure of a new city or a beach is always right outside my door, and sometimes it takes all my strength not to shut the computer and head off on an adventure.

Like everything, it’s a juggling act but we've implemented strategies to try to combat it such as not replying to emails after dinner or before breakfast and heading out into nature in some way every day.

And if we decide to swap things up for a few days, we can.

But the basic boundaries don’t change.”

Carey's kids going local

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

For families that have decided to untether fully and work remotely both before and during the pandemic, the ultimate beneficiary of that ability to blur the lines while maintaining boundaries are kids, says Carey.

“Working remotely we have the advantage that we’re not trying to replicate a typical school day or workday,” Carey tells me.

“So flexibility is the key for us.

Our children are doing an online school that’s self-paced so if we decide to do school in the afternoon instead of the morning, or skip a day mid-week to explore a museum or climb a mountain, then we can do that without consequence.

This also gives us some pretty great bargaining chips to encourage the kids to get their school done: ‘Want to go snorkeling this afternoon kids? Then get your schoolwork done!’”.

That flexibility, says Carey, leads to happier, better adjusted children.

“Living remotely on a boat has changed my kids.

They are quietly confident with an ability to converse with adults or children alike, yet they are friendly, welcoming and inclusive.

They don’t see anyone by age, sex, or color, instead they just see a playmate.

They’ve visited 15 countries, watched turtles laying eggs on the beach under a stary sky, climbed to the top of a volcano, seen animals they previously didn’t know existed, and ordered food in French, Spanish and Portuguese.

They’ve learned to entertain themselves with the simple pleasure of a book or rocks and sticks on a deserted beach, and also become experts in the weather, oceanography, the moon cycles and the geography of the world since we are always looking at maps and charts.

Happy kids, happy boat.

Happy boat, happy life.”

Happy boat, happy life.

Happy life, happy marriage.

Nick Fabbri and Terysa Venderloo

Happy life, happy marriage.

Nick Fabbri and Terysa Venderloo

Courtesy of Ryby Rose

So how much does it cost to sail around the world? Costs are important, and this week we talk about money and what experience has shown us.

As for the original question—is there now a remote office too far?—it doesn’t look like it.

What’s equally certain is that remote work, mobile lifestyles like the Careys’ and Fabbri and Vanderloo’s that were once fringe aren’t exiting the mainstream any time soon.

“When we started our YouTube channel, I didn't see it as a way of earning money,” says Vanderloo of the couple’s digital launch back in 2017.

“But as our channel grew and scope for income grew with it, we poured more and more time and energy into it and now have complete autonomy.

The pandemic has accelerated this shift towards remote work that was already underway, but perhaps not widely accepted by many companies due to the perception that you weren't as committed or productive if you were working from your home.

After a year of enforced remote working, many company owners are seeing the benefits and I don't think there's any turning back the clock on this one.

That's great news for people in their 20s, 30s, 40s too young to retire, but still wanting to live an alternative lifestyle.

They can carry on working from their boat or van or wherever, still earn income, and lead an amazing life.”

For Carey, who as a PR professional has the challenge of representing other digital nomads, travel influencers, and other mobile brands, the most essential transformation when it comes to remote work is how COVID-19 has forced a more global, cultural conversation.

“Digital nomads were often perceived as social media influencers sitting on the beach with a laptop drinking a cocktail out of a coconut,” Carey says.

“And I still think that we have a little way to go before that term ‘nomad’ isn’t fraught with skepticism.

But the pandemic has created a tipping point moment in my opinion and generated a dialog around digital nomadism where more and more people are questioning why they too can’t do their job from anywhere in the world.

In 20 years, my kids won’t sit in an office all day—not only because they are being raised on a boat, but because most jobs will be done remotely.

So as far as I’m concerned we’re just getting them better prepared.”

What’s equally certain is that remote work, mobile lifestyles like the Careys’ and Fabbri and Vanderloo’s that were once fringe aren’t exiting the mainstream any time soon.

“When we started our YouTube channel, I didn't see it as a way of earning money,” says Vanderloo of the couple’s digital launch back in 2017.

“But as our channel grew and scope for income grew with it, we poured more and more time and energy into it and now have complete autonomy.

The pandemic has accelerated this shift towards remote work that was already underway, but perhaps not widely accepted by many companies due to the perception that you weren't as committed or productive if you were working from your home.

After a year of enforced remote working, many company owners are seeing the benefits and I don't think there's any turning back the clock on this one.

That's great news for people in their 20s, 30s, 40s too young to retire, but still wanting to live an alternative lifestyle.

They can carry on working from their boat or van or wherever, still earn income, and lead an amazing life.”

For Carey, who as a PR professional has the challenge of representing other digital nomads, travel influencers, and other mobile brands, the most essential transformation when it comes to remote work is how COVID-19 has forced a more global, cultural conversation.

“Digital nomads were often perceived as social media influencers sitting on the beach with a laptop drinking a cocktail out of a coconut,” Carey says.

“And I still think that we have a little way to go before that term ‘nomad’ isn’t fraught with skepticism.

But the pandemic has created a tipping point moment in my opinion and generated a dialog around digital nomadism where more and more people are questioning why they too can’t do their job from anywhere in the world.

In 20 years, my kids won’t sit in an office all day—not only because they are being raised on a boat, but because most jobs will be done remotely.

So as far as I’m concerned we’re just getting them better prepared.”

I think I'll just keep working from here for now, thanks

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

As for when any of these new normal, remote work pioneers might be headed back to shore and re-embracing the lives they once knew?

“We have no plans to return to living on land,” Ruby Rose’s Fabbri and Vanderloo tell me.

“There are so many sailing adventures to be had.

It’s hard to imagine missing out on them at this point if we can make a digital living capturing those stories for others.”

Carey and her husband David don’t appear to be in any rush to ditch #yachtlife any time soon either.

“Our motto is ‘as long as it’s fun’,” says Carey.

“We’ve sold our house, our cars and all of our possessions to live this life.

This boat is our home.

Whether that ends up being 2 years, 5 years or 10 years, who knows? What I do know is that this lifestyle has given us a threshold for freedom, adventure, and autonomy that is much higher than what can be achieved living a normal life.

All of these experiences have made me stronger.

I am far more patient than I used to be and far more capable than I ever thought possible and it’s this sense of badassery that helps us grow as people.

As they say, nothing good happens in comfort zones.

So will we ever be happy living in the rat race again?”

Given the new remote work normal the pandemic has ushered in, I’ll take the odds on, “Probably not”.

No comments:

Post a Comment