NASA runs fake space missions on Earth. These simulations — called analog missions — allow scientists to study what a long space mission would be like for the crew.

Some analog missions study the use of specialized technology or the effects of zero gravity on the body, but others focus primarily on psychological effects.

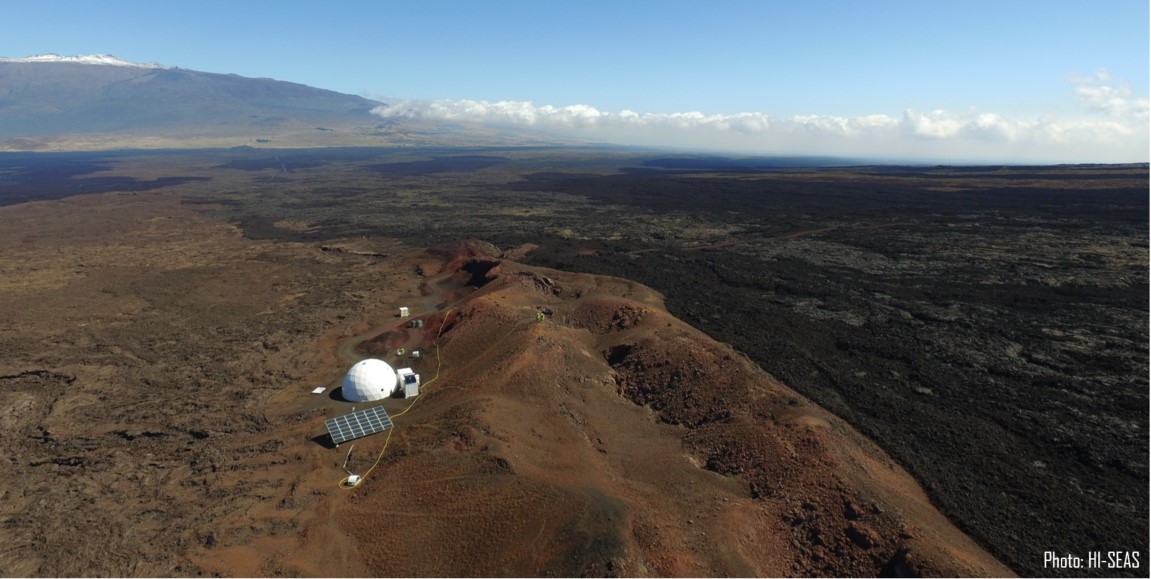

The HI-SEAS mission, or Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, takes place near the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii and is designed to simulate living on Mars.

Crew members live in isolation for about 8 months and aren't allowed to stray further than a mile or two from their small, dome-shaped habitat.

Scientists study the impact this has on the crew's mental and emotional state.

From Slate by Kate Green

I spent four months pretending to live on Mars.

Here’s what I learned about staying sane and passing time.

In 2013, I packed a bag and moved into a geodesic dome where I lived with five other people, all of us pretending to be astronauts on a mission to Mars.

It was a strange time in my life, but NASA funded it: an isolation experiment called HI-SEAS on the Hawaiian volcano Mauna Loa, where, for four months, our crew of six gave scientists our physical, psychological, and social health data in the hope that it might make a future trip to the red planet better for some hypothetical future crew.

The conditions of the experiment were such that we were cut off from family and friends with a 20-minute communication delay.

We had no fresh fruits or vegetables—only nonperishable foods.

And we couldn’t leave the dome unless we wore “spacesuits,” which were actually modified, oversize government surplus hazmat suits.

Little did I know how well the HI-SEAS experiment would prepare me for March 2020, Earth.

It can be maddening to be cooped up for months, as many already know: people with chronic illness, people with disabilities, those who are incarcerated, new mothers, graduate students, freelancers who work from home, and now people isolating themselves to stem the spread of the novel coronavirus.

This kind of isolation comes with significant psychosocial challenges.

Same goes for astronauts on a long duration mission.

So before sending them off on a 2½-year trip to Mars, NASA wants to understand what they’re up against and how to help them cope.

If these difficulties aren’t carefully considered in crew selection and mission design, any Mars-going effort could be for naught.

As Kim Binsted, professor at the University of Hawaii and head of HI-SEAS, has said, “If you think about a mission to Mars as being a system of systems, the human part of that system, if that breaks, can be just as disastrous as a rocket blowing up.”

Challenges include microstimuli that grow macro over time—the way your crewmate clears her throat every five minutes, for instance.

Frustrations continue with a crew-ground disconnect, where the crew loses faith in the ability of mission support to provide helpful or trustworthy information.

And then there’s boredom.

Boredom’s a big one.

It’s a strange torpor that can spur a person to action or give creative insights as well as lull them into an ever-deepening despair.

The fundamental difficulty of isolation is this: Humans are an adaptive species that thrives in changing environments.

“What isolation does is sort of remove that context of adaptation because when we’re isolated, we’re not … able to engage our environment in as many different ways,” says Tom Williams, element scientist for human factors and behavioral performance in the Human Research Program at NASA.

“So it sort of creates this barrier to allowing us to be that adaptive resilient human.”

One of the biggest differences between my simulated Mars mission and the isolation brought by measures to slow the spread of COVID-19 is the uncertainty.

The situation we all face now is rapidly changing as more people are asked to adjust their behaviors and restrict their movements, and no one knows for how long.

At the start of HI-SEAS, we knew the duration of the mission.

We were able to plan milestone celebrations and anticipate, without a doubt, the day we would return to Earth.

Right now, in our collective, scattered isolations, we aren’t so lucky.

Still, I believe that some of the approaches my crew and I took while isolated in that dome can apply to the current situation.

Perhaps some of these suggestions can ease the burden.

Make food special.

You’ve probably stocked up on some nonperishable goods.

Good.

All of our HI-SEAS food was shelf-stable, freeze-dried, or dehydrated, which actually allowed for many delicious meal possibilities.

(My crewmate Sian Proctor has a book and cooking videos that can give you an idea.) We experimented with new recipes and honored milestones and birthdays with multicourse dinners.

It really broke up the monotony.

Consider, if possible, novel, flavorful options that you might not normally eat as well as comfort foods.

Find a few new recipes.

Treat meals as a time to connect with others, savor a new experience, and find calm.

Journal

NASA recommends that astronauts keep a journal, which the agency can then use to learn about frustrations and help future spacefarers overcome them.

And, as many people on Earth already know, offloading stressful ruminations to the page can be a great relief.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is a historic time.

You likely won’t regret keeping some kind of record—words, pictures, videos—of your day-to-day life even if it is just what you ate for breakfast, a to-do list, or exactly how one of your quarantine mates is getting on your nerves.

Make rituals

Twice a week, as a crew, we met for movie nights.

Sometimes it felt like a drag and sometimes the movie selections of my crewmates were not to my taste (The House Bunny was not my favorite), but it always felt good to have a consistent event that marked the time, something to look forward to.

Time is slippery in isolation.

The more you can fix it, the better.

I also found it helpful to keep my hands busy.

Crafting and building things can help locate attention in the present moment.

Go outside

I wish I had done this more, but my own projects, which involved reading, writing, and organizing the crew’s sleep data, were indoor activities.

Plus, it took multiple people and at least 10 minutes to properly suit up.

The suits were bulky and cumbersome, and the walkie-talkie headsets seemed to always be cutting out.

Still, after every hike over the red lava fields of Mauna Loa, hearing the basalt crunch under my boots, peering into the dark openings of caves, squinting up at the sky trying to imagine it as a dusty red rather than crisp blue, I felt so much better.

Plus, picking up and holding a rock is a great reminder of deep time.

Eons have preceded us and eons will follow, which is, to me, a comforting thought.

If at all possible, take a walk, breathe fresh air, and soak in the sun while keeping a safe and healthy distance from others.

Socialize

Because Mars is very far away, and it can take up to 24 minutes to send data back to Earth, our communication was limited to asynchronous email conversations.

No FaceTime, no texting, but also no Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Kind of a relief, honestly.

I learned new ways to maintain my correspondences—daily emails, poems, and short video hellos—and it was such a critical part of maintaining and building relationships back home.

It will be equally important to stay in touch with friends and family isolated at a distance, but at least many of us share an internet that gives us the benefit of real-time interactions.

Already, virtual book clubs, performances, and coffee dates are happening all over the country.

Many classes, including the poetry workshop I teach at Columbia University, have moved online.

I now also have a grand plan to read War and Peace, spend more time with Rilke’s Duino Elegies, and maybe drop in on some drawing classes.

See how it feels to participate in some virtual events or online classes, or host one yourself.

Mix it up

Our crew scientist, Yajaira Sierra-Sastre, brought multiple biology experiments with her so that every couple of weeks, she’d have something new to focus on.

For our daily workouts, many of us used P90X, which offered built-in variety.

We also had an inflatable couch and chair so we could easily rearrange our common space.

Changing your environment is one way to interrupt boredom, so stagger all those projects you have hopes of completing, invite variation and change as an alternative to anxious uncertainty, and don’t be afraid to move your furniture, paint a wall, reorganize shelves, or make and hang new art.

Delight the senses

One thing that surprised me was how important scent was on our mission.

For the project’s main experiment, a food study, we took tests to determine how well we could identify odors.

The smell of fresh pineapple early in the mission made me surprisingly emotional, and later, a whiff of grass and then rubber from scratch-’n’-sniff (scientifically validated) booklets made me exceedingly wistful for life back on Earth.

Surround yourself with soft things, get flowers and plants while you can, smell essential oils and spices, watch strange movies, play your favorite video games, listen to music, take hot baths, stretch, take cold showers, remind yourself of your body.

Expect it to be hard

Even knowing the challenges of isolation and being somewhat temperamentally predisposed to dealing with them, I still couldn’t avoid them.

It was on Mars where I became intimate with my particular brand of boredom.

Before the mission, I presumed I was never bored, but what I learned was that I’m actually almost always bored, always looking for something new and interesting.

Over time with so much sameness, I slipped into a kind of low-arousal state that only mistaking a crewmate for an intruder shortly at one point snapped me out of.

When the isolation gets hard, and you feel frustration, annoyance, and boredom, try not to judge it or yourself too harshly.

Consider instead approaching it with curiosity like a scientist or an artist.

I came to HI-SEAS as a journalist and former scientist, but my experience inside that dome changed me.

In the years since, I’ve become a different kind of writer, one who spends more time with poetry and the associative, approaching ideas more obliquely now rather than straight on.

Be interested in your boredom and other difficult feelings.

Let them wash over you.

It’s possible that there’s something good waiting on the other side.

Remember your purpose

This one’s easy for astronauts, especially on a mission to Mars.

But our crew was working at a remove.

I must admit it took multistep mental contortions to convince myself that filling out all the daily surveys and enduring our own uncertainties—changes in experiment protocols, loss of electricity and plumbing, and sometimes confusing information from mission support—was important.

But when I did, it made a big difference.

Remembering that we were doing something that might be good for the future of human exploration and maybe even humanity kept me grounded when I wanted to be flying and let me fly when I felt heavy and stuck.

To be part of something historic, to do something potentially grand for others—it was remarkable how focusing on that was often enough.

And now here we are, so many of us staying at home, grappling with boredom, rolling with a rapidly changing situation, considering sustainable approaches, and trying to find calm amid it all.

It’s a mission none of us signed up for.

But still, it might be helpful to look at it like a mission with a very clear purpose and, when times get hard, hold onto that purpose.

Maybe, like me, you have the sense right now that we’re all traveling to an unexplored planet, some different version of Earth waiting to be revealed.

I believe my purpose on this journey is to do what I can to help keep a deadly virus from more seriously ravaging those in my community and beyond.

It will likely be uncomfortable and hard, and when it is, I’ll try to call back to this shared purpose and solidarity with others as often as possible.

It’s striking, I think, that through our forced isolation the true extent of our interconnectedness and reliance on one another is exposed.

Maybe it will help clear some paths to make all kinds of things better—both personally and socioeconomically—in the future.

We are all part of something historic and larger than ourselves.

At a time of great uncertainty, perhaps remembering this can be enough.

Links :

- Hawaii Herald Tribune : New HI-SEAS missions launch on Mauna Loa

- The Atlantic : When a Mars Simulation Goes Wrong

- The Guardian : 'Focus only on what you can control': A solo round-the-world sailor on isolation

- 11th Hour Racing : Self Isolation Hacks from Offshore Sailing

- YouTube : Chris Hadfield, An Astronaut's Guide to Self Isolation

CNN : Living an isolated life: Astronauts, Antarctic doctors and climbers share their advice

ReplyDeleteGeographical : Thoughts on isolation from the first British astronaut – Helen Sharman

ReplyDeleteThe Economist : Notes on isolation, from those who know it well

ReplyDelete