Sailors and members of the Applied Physics Laboratory Ice Station clear ice from the hatch of the Seawolf-class submarine USS Connecticut (SSN 22) as it surfaces above the ice during ICEX 2011. (Specialist 2nd Class Kevin S. O’Brien / U.S. Navy)

From WarOnTheRocks by Elizabeth Buchanan & Bec Strating

The South China Sea and the Arctic are increasingly grouped as strategic theaters rife with renewed great-power competition.

This sentiment permeates current affairs analysis, which features geopolitical links between the two maritime theaters.

And these assessments are not resigned to “hot takes” — the linkage features at senior policy levels, too.

Consider, for example, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s rhetorical question, “Do we want the Arctic Ocean to transform into a new South China Sea, fraught with militarization and competing territorial claims?”

To what extent are China’s challenges to maritime order in the South China Sea a signal for how it will approach the Arctic? Understanding the differences as well as the similarities between the South China Sea and Arctic geopolitical “competitions” is crucial to predicting the strategic implications of future maritime posturing and policies from Beijing.

Comparing the South China Sea flashpoint and the Arctic in the context of strategic competition highlights how maritime “revisionism” is better understood as maritime exceptionalism.

Yet comparisons often fail to provide an accurate picture of the internal geopolitical climates in each region, and we argue that it is too simplistic to extrapolate the trends in one theater and apply them to the other.

China and Russia approach the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in a localized and interest-based way when it comes to the South China Sea and Arctic regions.

These localized approaches to the law of the sea has implications for understanding challenges to multilateral rules-based governance of the global commons.

The South China Sea and the Arctic are increasingly grouped as strategic theaters rife with renewed great-power competition.

This sentiment permeates current affairs analysis, which features geopolitical links between the two maritime theaters.

And these assessments are not resigned to “hot takes” — the linkage features at senior policy levels, too.

Consider, for example, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s rhetorical question, “Do we want the Arctic Ocean to transform into a new South China Sea, fraught with militarization and competing territorial claims?”

To what extent are China’s challenges to maritime order in the South China Sea a signal for how it will approach the Arctic? Understanding the differences as well as the similarities between the South China Sea and Arctic geopolitical “competitions” is crucial to predicting the strategic implications of future maritime posturing and policies from Beijing.

Comparing the South China Sea flashpoint and the Arctic in the context of strategic competition highlights how maritime “revisionism” is better understood as maritime exceptionalism.

Yet comparisons often fail to provide an accurate picture of the internal geopolitical climates in each region, and we argue that it is too simplistic to extrapolate the trends in one theater and apply them to the other.

China and Russia approach the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in a localized and interest-based way when it comes to the South China Sea and Arctic regions.

These localized approaches to the law of the sea has implications for understanding challenges to multilateral rules-based governance of the global commons.

The Same, but Different

Both the South China Sea and Arctic are home to increasing great-power naval posturing, featuring active great powers intent on making maritime claims inconsistent with UNCLOS and asserting exceptional jurisdictional rights.

The unwillingness of the United States to ratify UNCLOS — while claiming that the portions of UNCLOS related to maritime claims have status and power as customary international law — makes the legal and institutional picture murkier.

Yet the extent to which the South China Sea and the Arctic are comparable as “contested commons” is limited.

First, there are crucial geographical differences.

Although the Arctic is the world’s smallest ocean, it is still five times larger than the South China Sea, and home to delineated maritime spaces and functioning rules of the game in the region.

The portion of the Central Arctic Ocean outside of claimed territorial waters and exclusive economic zones is roughly the size of the Mediterranean Sea.

Despite popular connotations of “new Cold Wars” and clashes in the Arctic, the region is home to long-standing maritime agreements, many treaties (including on search and rescue, and oil spill responses) negotiated between and among Arctic states, and is governed by the consensus-based Arctic Council.

It is a zone in which the renewed tensions between Russia and the West are largely absent, and remains a region of international cooperation and coordination.

Five Arctic Ocean coastal states have exclusive economic zones which extend out into various seas (the Greenland, Norwegian, Barents, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas) above the Arctic Circle, which in turn form the Arctic Ocean.

China has anointed itself as a “near-Arctic State,” viewing the Central Arctic Ocean as a global commons.

In contrast to the relative harmony and cooperation in the Arctic, the South China Sea is a hotbed of disagreement and competition.

Encompassing over 3 million square kilometers, the South China Sea is subject to a range of overlapping claims over land features and jurisdictions, including sovereignty over islands and rocks, control of low-lying features such as reefs and shoals, the classification of land features, control of resources, and freedom of navigation.

Contests over exclusive economic zones abound.

Furthermore, China claims “sovereign rights” within the nine-dash line (approximately 90 percent of the South China Sea), a claim which was quashed by the ruling of 2016 South China Sea Arbitral Tribunal.

Beijing has rejected and largely ignored that ruling.

Sovereignty disputes concern the ownership of the hundreds of features dotting the sea, including islands, rocks, reefs, submerged shoals, and low-lying elevations, some or all of which are claimed by China, Taiwan, Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

Sovereignty of these land features and their classification — as islands, rocks, or low-lying elevations — affect the rights to maritime resources, such as oil, gas, and fish.

The above five states, plus Brunei and Indonesia, claim exclusive economic zones and continental shelf in the South China Sea beyond their mainland and archipelagic baselines.

Under international law, these maritime zones entitle states to limited sovereign rights (i.e., to resources), rather than full sovereignty.

Strategic competition at sea has been at least partly driven by China’s rising naval militarization.

The South China Sea is considered a “near sea” and its geographic proximity to the mainland is central to the China’s strategic imagination and threat perception.

In addition to conventional concerns about territorial defense, the South China Sea is also important for China because of its nationalist claims to all of the tiny land features, and its desire to exploit resources such as oil, gas, and fish.

This has also contributed to the growing militarization of the South China Sea.

In addition, six of China’s 10 largest ports can only be reached via this body of water.

These geographical differences render it too simplistic to extrapolate the geopolitics of the South China Sea to the Arctic.

This is further illustrated by drilling down into the differences in the strategic trajectories in terms of the balance of power and international legal norms.

Both the South China Sea and Arctic are home to increasing great-power naval posturing, featuring active great powers intent on making maritime claims inconsistent with UNCLOS and asserting exceptional jurisdictional rights.

The unwillingness of the United States to ratify UNCLOS — while claiming that the portions of UNCLOS related to maritime claims have status and power as customary international law — makes the legal and institutional picture murkier.

Yet the extent to which the South China Sea and the Arctic are comparable as “contested commons” is limited.

First, there are crucial geographical differences.

Although the Arctic is the world’s smallest ocean, it is still five times larger than the South China Sea, and home to delineated maritime spaces and functioning rules of the game in the region.

The portion of the Central Arctic Ocean outside of claimed territorial waters and exclusive economic zones is roughly the size of the Mediterranean Sea.

Despite popular connotations of “new Cold Wars” and clashes in the Arctic, the region is home to long-standing maritime agreements, many treaties (including on search and rescue, and oil spill responses) negotiated between and among Arctic states, and is governed by the consensus-based Arctic Council.

It is a zone in which the renewed tensions between Russia and the West are largely absent, and remains a region of international cooperation and coordination.

Five Arctic Ocean coastal states have exclusive economic zones which extend out into various seas (the Greenland, Norwegian, Barents, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas) above the Arctic Circle, which in turn form the Arctic Ocean.

China has anointed itself as a “near-Arctic State,” viewing the Central Arctic Ocean as a global commons.

In contrast to the relative harmony and cooperation in the Arctic, the South China Sea is a hotbed of disagreement and competition.

Encompassing over 3 million square kilometers, the South China Sea is subject to a range of overlapping claims over land features and jurisdictions, including sovereignty over islands and rocks, control of low-lying features such as reefs and shoals, the classification of land features, control of resources, and freedom of navigation.

Contests over exclusive economic zones abound.

Furthermore, China claims “sovereign rights” within the nine-dash line (approximately 90 percent of the South China Sea), a claim which was quashed by the ruling of 2016 South China Sea Arbitral Tribunal.

Beijing has rejected and largely ignored that ruling.

Sovereignty disputes concern the ownership of the hundreds of features dotting the sea, including islands, rocks, reefs, submerged shoals, and low-lying elevations, some or all of which are claimed by China, Taiwan, Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

Sovereignty of these land features and their classification — as islands, rocks, or low-lying elevations — affect the rights to maritime resources, such as oil, gas, and fish.

The above five states, plus Brunei and Indonesia, claim exclusive economic zones and continental shelf in the South China Sea beyond their mainland and archipelagic baselines.

Under international law, these maritime zones entitle states to limited sovereign rights (i.e., to resources), rather than full sovereignty.

Strategic competition at sea has been at least partly driven by China’s rising naval militarization.

The South China Sea is considered a “near sea” and its geographic proximity to the mainland is central to the China’s strategic imagination and threat perception.

In addition to conventional concerns about territorial defense, the South China Sea is also important for China because of its nationalist claims to all of the tiny land features, and its desire to exploit resources such as oil, gas, and fish.

This has also contributed to the growing militarization of the South China Sea.

In addition, six of China’s 10 largest ports can only be reached via this body of water.

These geographical differences render it too simplistic to extrapolate the geopolitics of the South China Sea to the Arctic.

This is further illustrated by drilling down into the differences in the strategic trajectories in terms of the balance of power and international legal norms.

Who owns the Arctic

Territorial claims of countries in the Arctic are being spurred by the presence of large caches of oil and natural gas, melting ice and dwindling energy reserves in other regions

source NYTimes

Balance of Power

Beginning in 2014, China engaged in rapid, large-scale militarization and artificial island-building in the South China Sea, raising alarm about its capacities and willingness to restrict navigation and exert sea control of this localized area.

Despite pledging not to militarize the islands, China took advantage of the geographic isolation and limited surveillance of these remote features to build three large, mid-ocean airfields suitable for military aircraft in 2016.

While some other claimant states also engaged in artificial island-building and militarization activities, China played a substantial role in militarizing the South China Sea, for example in emplacing anti-ship missiles and long-range surface-to-air missiles on artificial islands, contesting the transit of warships, and using maritime paramilitary forces for surveillance and intimidation of non-Chinese vessels.

These activities have precipitated new concerns about China’s intentions, including whether it wants to push the United States out of the first island chain.

These actions have precipitated concerns that China aims to revise and supplant or ignore maritime rules, with follow-on consequences for regional order more generally.

They directly challenge U.S. naval supremacy in the region.

China’s actions threaten U.S. interests in freedom of navigation and undermine the global maritime order, which has enabled the U.S. Navy to project power and enforce free transit for decades.

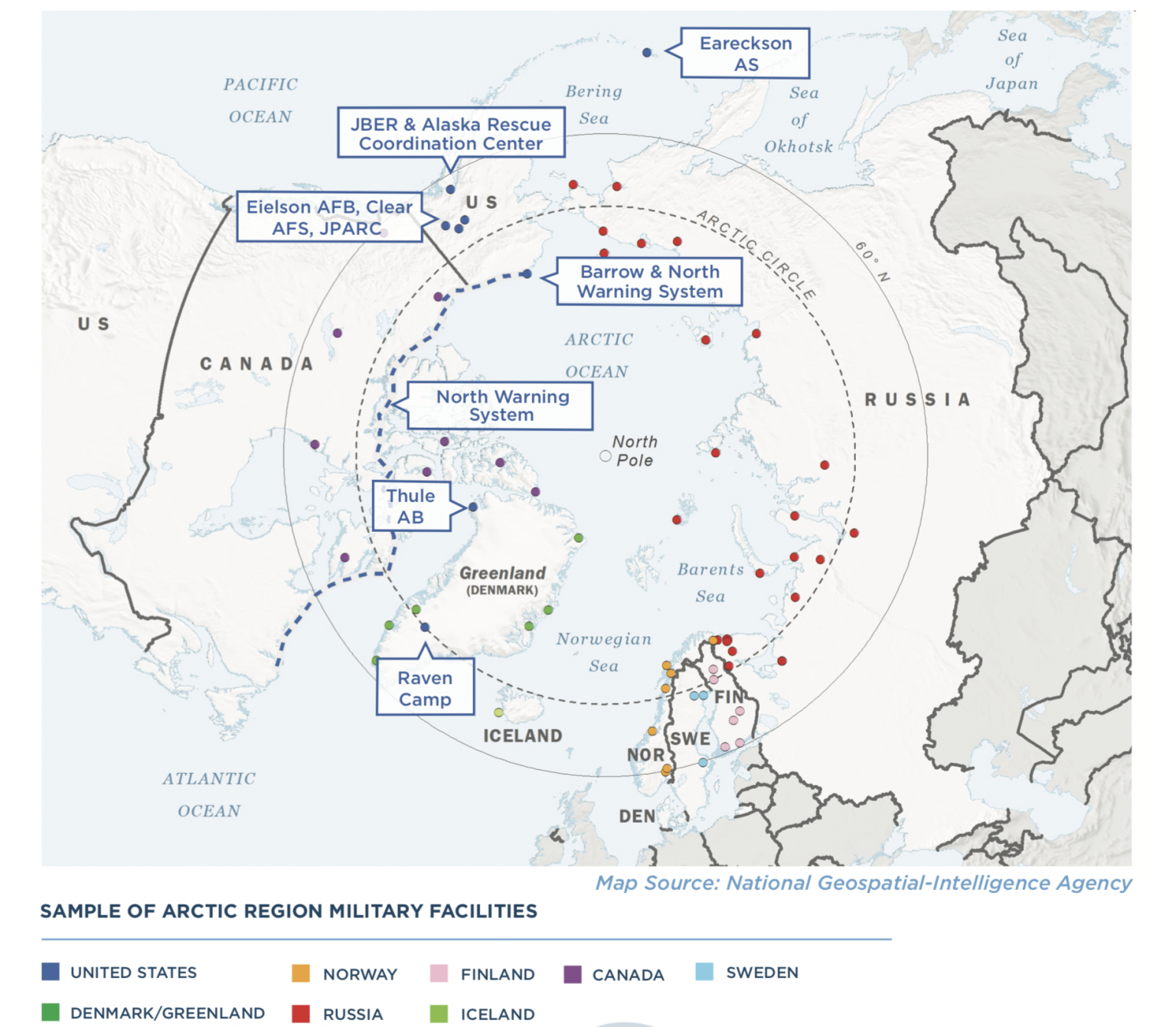

By contrast, in the Arctic, balance-of-power realities and great-power politics are not new.

The region is no stranger to geopolitical competition — it was a crucial battleground during the Cold War, as it is the shortest distance for missiles to fly between the United States and Soviet Union.

Further, the Arctic represented a key flank for NATO and strategically critical sea line of communication for wartime replenishment between Europe and North America.

Since the Cold War, regional cooperation and U.S.-Russian ties have remained somewhat siloed from tensions beyond the Arctic.

While new players and prizes have emerged in the Arctic “great game,” regional cooperation remains.

Of course, the preexisting U.S.-Russian power balance in the Arctic is an important consideration when adding Beijing to the Arctic power mix.

U.S. Arctic policy in recent years has been revived as part of a broader focus on renewed great-power competition.

Under the Trump administration, there has been a litany of Arctic updates — the Department of Defense, Air Force, and Coast Guard have all tabled new arctic strategies.

Increasingly, China is employing geoeconomics, rather than rapid militarization as seen in the South China Sea, to tilt the balance of power in the Arctic.

Beijing uses campaigns targeted toward the Nordic states and within the resource sector to increase influence, legitimacy, and engagement in the Arctic region.

Chinese economic engagement in Greenland’s resource sector, as well as its growing (albeit ever so slightly) economic ties in Iceland and Norway, are illustrative of China’s efforts to expand its role in the Arctic economy.

Much of China’s foreign investment in Arctic energy ventures is targeted at the Russian Arctic zone — particularly the liquefied national gas projects on the Yamal Peninsula.

However, Kremlin awareness of the potential debt-trap diplomacy Beijing undertakes has resulted in a unified Russian policy to curtail majority ownership by China of any Russian Arctic ventures.

Efforts in the South China Sea to increase cooperation — such as code of conduct negotiations between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or joint development plans — are failing to develop robust cooperative mechanisms for the management or resolution of maritime and territorial disputes.

In contrast, Washington’s balance-of-power considerations for the Arctic region tend to overstate the conflictual nature of the region — which, unlike its Cold War predecessor, is an environment characterized by international cooperation.

The U.S. interests are also different across the maritime theaters: In the South China Sea, the America’s primary interest has traditionally been cast as freedom of navigation and maintaining the capacity to maneuver within the first island chain, although recent diplomatic efforts have seen the United States provide more public support for the maritime rights of Southeast Asian claimant states.

In the Arctic, U.S. interests are primarily territorial, as it is one of five Arctic Ocean coastal states.

The Arctic is also a region through which Washington shares a border with Russia in the Bering Strait.

Additionally, there are vast resource interests in the Alaskan Arctic sector, an indigenous population, and strategic basing interests for power projection into the North Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific Oceans.

Hydrocarbon (oil and natural gas) resource exploitation is a clear driver of the South China Sea and Arctic “great games.” The Arctic is often touted, as per the U.S. Geological Survey, to hold an estimated 30 percent of the world’s remaining gas and 13% of its untapped oil reserves.

Of course, the majority of these estimates fall within zones of the Arctic which are not disputed, clearly within delineated territories.

On the high seas of the Arctic Ocean, Chinese activity remains focused on scientific and research priorities, at least for now.

China is party to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, and while it is legally allowed to exploit the Central Arctic Ocean region, Beijing has continued to abide by the fisheries ban.

In the South China Sea, on the other hand, China has been aggressively attempting to deny Southeast Asian claimant states their legal entitlements to maritime resources under UNCLOS.

One of the contemporary challenges posed in the South China Sea are the so-called “gray zone tactics” employed by China’s paranaval forces to assert its claims to disputed land features and adjacent waters.

Described as a “cabbage strategy,” China’s maritime coast guard, fishing fleets, and maritime militia form layers of pressure that constitute its first line of maritime defense.

China’s proximity to the South China Sea allows it to use its growing number of maritime assets to implement its gray zone tactics to advance its claims.

In contrast, China’s naval capabilities are not yet advanced enough to project power in the more distant and complex Arctic high seas environment.

International Legal Norms

Distorting international legal norms is a central element of China’s South China Sea approach.

Although it has engaged in a “lawfare” strategy to support its territorial and maritime interests in the South China Sea, many of its pseudo-legal arguments are inconsistent with UNCLOS.

Possibly the highest profile are Beijing’s claims to “historic rights” inside the nine-dash line, which would give China sovereignty over land features as well as sovereign rights to fishing, navigation, and exploration and exploitation of resources.

This argument was rejected by an Arbitral Tribunal instituted under UNCLOS in 2016, which Beijing has refused to acknowledge as binding or legitimate.

The second ambit claim is China’s Four Sha (four sands) strategy, which involves constructing straight archipelagic baselines around the island groups of the Pratas Islands, Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands, and Macclesfield Bank.

Here, Beijing lawyers and academics have developed a new legal theory that the Four Sha are China’s historical territorial waters and part of its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, even though the offshore archipelagos do not conform with standards for drawing straight archipelagic baselines set out in Article 47 of UNCLOS, which states that the ratio of the area of the water to the area of the land must be between one to one and nine to one.

In these South China Sea island groups, the water area is too large to meet these requirements.

Nevertheless, the Four Sha theory indicates a desire to claim internal waters within such baselines, which, if successful, would entitle China to full sovereignty over the area rather than the limited sovereign rights afforded in other maritime zones such as the exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

The third concerning element of China’s lawfare strategy is the use of domestic law to justify double standards in implementing principles of freedom of navigation.

For example, the U.S. interpretation that innocent passage includes warships without prior notification is not universally shared.

Some legal scholars argue that the assertion of greater security rights at sea is a sign of creeping jurisdiction by coastal states .

For example, Beijing asserts its right to regulate foreign military activities in its claimed exclusive economic zone, contrary to widespread understandings of UNCLOS provisions.

Beijing has presented the South China Sea as a sui generis area subject to Chinese domestic law, rather than international law, which constitutes a form of jurisdictional exceptionalism.

Yet in the Arctic Ocean, Beijing has continued to adhere to the agreed international legal architecture, despite its increased footprint and interest in the region.

Like the South China Sea, the international shipping routes emerging from the melting Arctic zone are eyed by Beijing as a key component of the Polar Silk Road aspect of their Belt and Road Initiative.

For now, China looks to use the most viable Asia-to-Europe shipping passage — the Northeast Passage.

A large section of the Northeast Passage is Russia’s Northern Sea Route, an international waterway defined by Russian law.

In the Northern Sea Route, Russia has somewhat mimicked China’s jurisdictional exceptionalism in the South China Sea.

Russia argues that the Northern Sea Route constitutes “straits used for internal navigation,” and is thus not subject to all UNCLOS rights like innocent passage.

Russia’s application of UNCLOS Article 234 (commonly known as the ice law) stipulates that states can enhance their sovereignty and control over an exclusive economic zone if the area is subject to ice coverage or grounds for intensified environmental management.

Moscow has long applied this entirely legal approach and developed deeper jurisdictional exceptionalism in recent years.

Russia has crafted domestic laws and implemented strategies for the management of the Northern Sea Route.

Examples include laws requiring Russian pilotage of all vessels transiting through the Northern Sea Route, toll fees, and prior warning or indication of plans to use the route.

The United States makes its own tantalizing jurisdictional exceptionalism effort by refusing to ratify UNCLOS while expecting others to conform to it.

In a broad sense, the three great powers across these maritime regions — the United States, China, and Russia — appeal to jurisdictional exceptionalism, but such great-power privileges are applied inconsistently according to geography and interests.

Such exceptionalism has worrying implications for the capacities of global governance regimes to enforce global standards that apply to all states.

China defends its jurisdictional exceptionalism in the South China Sea, yet is slowly starting to reject Russia’s application of the same exceptionalism and historical argument for its Arctic exclusive economic zone.

This is particularly the case for the Northern Sea Route.

Beijing is increasingly opting not to refer to the Northern Sea Route at all, speaking merely in terms of the Northeast Passage.

While double standards are nothing new in international politics, it is interesting to witness the ways in which states pick and choose, manipulate, and artfully interpret international law to fit agendas.

It’s Geography, Stupid

There are clear indicators of Chinese revisionism at sea extending beyond the South China Sea into the Arctic.

Both regions are a portent for how agreed-upon international rules are applied in divergent ways across different settings toward diverse strategic outcomes.

Lumping the Arctic and South China Sea into one basket as theaters hosting Chinese maritime revisionism, as if the exact same strategy is unleashed in all maritime strategy, clouds the reality of the two regions’ distinct strategic environments.

A constant across both flashpoints is the significant role that geography plays.

Geographical proximity has allowed China to use the nine-dash line to justify an extension of its land boundaries out to sea.

This is a form of mapped territorialization which is now even implicating popular culture and media.

This is possible in large part due to the proximity of the South China Sea to mainland China.

Russia has also used geographical proximity to bolster domestic narratives of Arctic greatness and to justify its Northern Sea Route exceptionalism.

China’s 2018 Arctic Strategy flagged Beijing’s “near-Arctic” identity and has cemented Beijing’s strategic interest in the region, yet it is unlikely that a mapped territorialization will result in the Arctic.

Beijing’s lack of proximity to the Arctic is somewhat a revenge of geography that not only curtails China’s ability to legitimize itself amongst Arctic-rim powers, but is also a constraining factor for any domestic public relations agenda in China.

China’s Four Sha strategy is based on an assumption of sovereign ownership of contested land features in the South China Sea.

Russia, too, bases its extended continental shelf claim on contested features of the Arctic.

This claim is currently under consideration at the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf .

The underwater ridge which Russia argues is an extension of the Siberian continental shelf extends up to the North Pole along the Arctic Ocean seabed.

This ridge is also claimed by Denmark (by way of Greenland) and Canada.

The three states will likely deliberate between themselves any extended exclusive economic zone claims, given that the commission is unable to award territory and merely rules on the scientific evidence presented.

Contested land features are a hallmark of the current overlapping claims to the North Pole, but there is no avenue for China to tap into this particular contest of land features in the Arctic.

There is, however, the potential for China to claim ice floes in the high seas region of the Arctic Ocean — perhaps to even fortify or build its own floating feature in this region, climate change allowing.

In reality, this is unlikely due to the sheer operational challenges, none the least periods of 24-hour darkness, and a harsh operational environment which makes no commercial sense nor provides any limited strategic pay-off to repeating its South China Sea approach in the Arctic.

Overall, the South China Sea and the Arctic are very different maritime regions with distinct geopolitical characteristics.

China is clearly borrowing from the great-power exceptionalism playbook in the South China Sea.

Yet while Beijing has articulated a clear strategic interest in the Arctic, a replication of its South China Sea play book in the Arctic is highly unlikely.

Maritime exceptionalism in approaches to UNCLOS are localized and interest-based according to geography, rather than generalized and values-based seeking wholescale revision of the “rules-based international order.”

Beginning in 2014, China engaged in rapid, large-scale militarization and artificial island-building in the South China Sea, raising alarm about its capacities and willingness to restrict navigation and exert sea control of this localized area.

Despite pledging not to militarize the islands, China took advantage of the geographic isolation and limited surveillance of these remote features to build three large, mid-ocean airfields suitable for military aircraft in 2016.

While some other claimant states also engaged in artificial island-building and militarization activities, China played a substantial role in militarizing the South China Sea, for example in emplacing anti-ship missiles and long-range surface-to-air missiles on artificial islands, contesting the transit of warships, and using maritime paramilitary forces for surveillance and intimidation of non-Chinese vessels.

These activities have precipitated new concerns about China’s intentions, including whether it wants to push the United States out of the first island chain.

These actions have precipitated concerns that China aims to revise and supplant or ignore maritime rules, with follow-on consequences for regional order more generally.

They directly challenge U.S. naval supremacy in the region.

China’s actions threaten U.S. interests in freedom of navigation and undermine the global maritime order, which has enabled the U.S. Navy to project power and enforce free transit for decades.

By contrast, in the Arctic, balance-of-power realities and great-power politics are not new.

The region is no stranger to geopolitical competition — it was a crucial battleground during the Cold War, as it is the shortest distance for missiles to fly between the United States and Soviet Union.

Further, the Arctic represented a key flank for NATO and strategically critical sea line of communication for wartime replenishment between Europe and North America.

Since the Cold War, regional cooperation and U.S.-Russian ties have remained somewhat siloed from tensions beyond the Arctic.

While new players and prizes have emerged in the Arctic “great game,” regional cooperation remains.

Of course, the preexisting U.S.-Russian power balance in the Arctic is an important consideration when adding Beijing to the Arctic power mix.

U.S. Arctic policy in recent years has been revived as part of a broader focus on renewed great-power competition.

Under the Trump administration, there has been a litany of Arctic updates — the Department of Defense, Air Force, and Coast Guard have all tabled new arctic strategies.

Increasingly, China is employing geoeconomics, rather than rapid militarization as seen in the South China Sea, to tilt the balance of power in the Arctic.

Beijing uses campaigns targeted toward the Nordic states and within the resource sector to increase influence, legitimacy, and engagement in the Arctic region.

Chinese economic engagement in Greenland’s resource sector, as well as its growing (albeit ever so slightly) economic ties in Iceland and Norway, are illustrative of China’s efforts to expand its role in the Arctic economy.

Much of China’s foreign investment in Arctic energy ventures is targeted at the Russian Arctic zone — particularly the liquefied national gas projects on the Yamal Peninsula.

However, Kremlin awareness of the potential debt-trap diplomacy Beijing undertakes has resulted in a unified Russian policy to curtail majority ownership by China of any Russian Arctic ventures.

Efforts in the South China Sea to increase cooperation — such as code of conduct negotiations between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or joint development plans — are failing to develop robust cooperative mechanisms for the management or resolution of maritime and territorial disputes.

In contrast, Washington’s balance-of-power considerations for the Arctic region tend to overstate the conflictual nature of the region — which, unlike its Cold War predecessor, is an environment characterized by international cooperation.

The U.S. interests are also different across the maritime theaters: In the South China Sea, the America’s primary interest has traditionally been cast as freedom of navigation and maintaining the capacity to maneuver within the first island chain, although recent diplomatic efforts have seen the United States provide more public support for the maritime rights of Southeast Asian claimant states.

In the Arctic, U.S. interests are primarily territorial, as it is one of five Arctic Ocean coastal states.

The Arctic is also a region through which Washington shares a border with Russia in the Bering Strait.

Additionally, there are vast resource interests in the Alaskan Arctic sector, an indigenous population, and strategic basing interests for power projection into the North Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific Oceans.

Hydrocarbon (oil and natural gas) resource exploitation is a clear driver of the South China Sea and Arctic “great games.” The Arctic is often touted, as per the U.S. Geological Survey, to hold an estimated 30 percent of the world’s remaining gas and 13% of its untapped oil reserves.

Of course, the majority of these estimates fall within zones of the Arctic which are not disputed, clearly within delineated territories.

On the high seas of the Arctic Ocean, Chinese activity remains focused on scientific and research priorities, at least for now.

China is party to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, and while it is legally allowed to exploit the Central Arctic Ocean region, Beijing has continued to abide by the fisheries ban.

In the South China Sea, on the other hand, China has been aggressively attempting to deny Southeast Asian claimant states their legal entitlements to maritime resources under UNCLOS.

One of the contemporary challenges posed in the South China Sea are the so-called “gray zone tactics” employed by China’s paranaval forces to assert its claims to disputed land features and adjacent waters.

Described as a “cabbage strategy,” China’s maritime coast guard, fishing fleets, and maritime militia form layers of pressure that constitute its first line of maritime defense.

China’s proximity to the South China Sea allows it to use its growing number of maritime assets to implement its gray zone tactics to advance its claims.

In contrast, China’s naval capabilities are not yet advanced enough to project power in the more distant and complex Arctic high seas environment.

International Legal Norms

Distorting international legal norms is a central element of China’s South China Sea approach.

Although it has engaged in a “lawfare” strategy to support its territorial and maritime interests in the South China Sea, many of its pseudo-legal arguments are inconsistent with UNCLOS.

Possibly the highest profile are Beijing’s claims to “historic rights” inside the nine-dash line, which would give China sovereignty over land features as well as sovereign rights to fishing, navigation, and exploration and exploitation of resources.

This argument was rejected by an Arbitral Tribunal instituted under UNCLOS in 2016, which Beijing has refused to acknowledge as binding or legitimate.

The second ambit claim is China’s Four Sha (four sands) strategy, which involves constructing straight archipelagic baselines around the island groups of the Pratas Islands, Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands, and Macclesfield Bank.

Here, Beijing lawyers and academics have developed a new legal theory that the Four Sha are China’s historical territorial waters and part of its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, even though the offshore archipelagos do not conform with standards for drawing straight archipelagic baselines set out in Article 47 of UNCLOS, which states that the ratio of the area of the water to the area of the land must be between one to one and nine to one.

In these South China Sea island groups, the water area is too large to meet these requirements.

Nevertheless, the Four Sha theory indicates a desire to claim internal waters within such baselines, which, if successful, would entitle China to full sovereignty over the area rather than the limited sovereign rights afforded in other maritime zones such as the exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

The third concerning element of China’s lawfare strategy is the use of domestic law to justify double standards in implementing principles of freedom of navigation.

For example, the U.S. interpretation that innocent passage includes warships without prior notification is not universally shared.

Some legal scholars argue that the assertion of greater security rights at sea is a sign of creeping jurisdiction by coastal states .

For example, Beijing asserts its right to regulate foreign military activities in its claimed exclusive economic zone, contrary to widespread understandings of UNCLOS provisions.

Beijing has presented the South China Sea as a sui generis area subject to Chinese domestic law, rather than international law, which constitutes a form of jurisdictional exceptionalism.

Yet in the Arctic Ocean, Beijing has continued to adhere to the agreed international legal architecture, despite its increased footprint and interest in the region.

Like the South China Sea, the international shipping routes emerging from the melting Arctic zone are eyed by Beijing as a key component of the Polar Silk Road aspect of their Belt and Road Initiative.

For now, China looks to use the most viable Asia-to-Europe shipping passage — the Northeast Passage.

A large section of the Northeast Passage is Russia’s Northern Sea Route, an international waterway defined by Russian law.

In the Northern Sea Route, Russia has somewhat mimicked China’s jurisdictional exceptionalism in the South China Sea.

Russia argues that the Northern Sea Route constitutes “straits used for internal navigation,” and is thus not subject to all UNCLOS rights like innocent passage.

Russia’s application of UNCLOS Article 234 (commonly known as the ice law) stipulates that states can enhance their sovereignty and control over an exclusive economic zone if the area is subject to ice coverage or grounds for intensified environmental management.

Moscow has long applied this entirely legal approach and developed deeper jurisdictional exceptionalism in recent years.

Russia has crafted domestic laws and implemented strategies for the management of the Northern Sea Route.

Examples include laws requiring Russian pilotage of all vessels transiting through the Northern Sea Route, toll fees, and prior warning or indication of plans to use the route.

The United States makes its own tantalizing jurisdictional exceptionalism effort by refusing to ratify UNCLOS while expecting others to conform to it.

In a broad sense, the three great powers across these maritime regions — the United States, China, and Russia — appeal to jurisdictional exceptionalism, but such great-power privileges are applied inconsistently according to geography and interests.

Such exceptionalism has worrying implications for the capacities of global governance regimes to enforce global standards that apply to all states.

China defends its jurisdictional exceptionalism in the South China Sea, yet is slowly starting to reject Russia’s application of the same exceptionalism and historical argument for its Arctic exclusive economic zone.

This is particularly the case for the Northern Sea Route.

Beijing is increasingly opting not to refer to the Northern Sea Route at all, speaking merely in terms of the Northeast Passage.

While double standards are nothing new in international politics, it is interesting to witness the ways in which states pick and choose, manipulate, and artfully interpret international law to fit agendas.

It’s Geography, Stupid

There are clear indicators of Chinese revisionism at sea extending beyond the South China Sea into the Arctic.

Both regions are a portent for how agreed-upon international rules are applied in divergent ways across different settings toward diverse strategic outcomes.

Lumping the Arctic and South China Sea into one basket as theaters hosting Chinese maritime revisionism, as if the exact same strategy is unleashed in all maritime strategy, clouds the reality of the two regions’ distinct strategic environments.

A constant across both flashpoints is the significant role that geography plays.

Geographical proximity has allowed China to use the nine-dash line to justify an extension of its land boundaries out to sea.

This is a form of mapped territorialization which is now even implicating popular culture and media.

This is possible in large part due to the proximity of the South China Sea to mainland China.

Russia has also used geographical proximity to bolster domestic narratives of Arctic greatness and to justify its Northern Sea Route exceptionalism.

China’s 2018 Arctic Strategy flagged Beijing’s “near-Arctic” identity and has cemented Beijing’s strategic interest in the region, yet it is unlikely that a mapped territorialization will result in the Arctic.

Beijing’s lack of proximity to the Arctic is somewhat a revenge of geography that not only curtails China’s ability to legitimize itself amongst Arctic-rim powers, but is also a constraining factor for any domestic public relations agenda in China.

China’s Four Sha strategy is based on an assumption of sovereign ownership of contested land features in the South China Sea.

Russia, too, bases its extended continental shelf claim on contested features of the Arctic.

This claim is currently under consideration at the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf .

The underwater ridge which Russia argues is an extension of the Siberian continental shelf extends up to the North Pole along the Arctic Ocean seabed.

This ridge is also claimed by Denmark (by way of Greenland) and Canada.

The three states will likely deliberate between themselves any extended exclusive economic zone claims, given that the commission is unable to award territory and merely rules on the scientific evidence presented.

Contested land features are a hallmark of the current overlapping claims to the North Pole, but there is no avenue for China to tap into this particular contest of land features in the Arctic.

There is, however, the potential for China to claim ice floes in the high seas region of the Arctic Ocean — perhaps to even fortify or build its own floating feature in this region, climate change allowing.

In reality, this is unlikely due to the sheer operational challenges, none the least periods of 24-hour darkness, and a harsh operational environment which makes no commercial sense nor provides any limited strategic pay-off to repeating its South China Sea approach in the Arctic.

Overall, the South China Sea and the Arctic are very different maritime regions with distinct geopolitical characteristics.

China is clearly borrowing from the great-power exceptionalism playbook in the South China Sea.

Yet while Beijing has articulated a clear strategic interest in the Arctic, a replication of its South China Sea play book in the Arctic is highly unlikely.

Maritime exceptionalism in approaches to UNCLOS are localized and interest-based according to geography, rather than generalized and values-based seeking wholescale revision of the “rules-based international order.”

This has implications for understanding challenges to multilateral governance of the global commons, particularly for how states seeking to preserve norm-based standards should calibrate their policies according to specific geographical regions, rather than relying upon a generic appeal to a “rules-based order.”

Links :

- The organization for World peace : Climate Change, Geopolitics And The Arctic

No comments:

Post a Comment