Satellites are spying illegal fishing from space

From Hakai Magazine by Mara Johnson-Groh

Five hundred kilometers off the coast of Ecuador, the American Eagle, a purse seiner, meets a refrigerated cargo ship.

The two ships drift slowly together in the tropical water for eight hours.

Encounters like this are common practice, allowing ships on long fishing voyages to refuel and transfer their catch—likely what the two ships were doing.

But the practice, called transshipment, can also disguise nefarious acts, such as smuggling illegally caught fish or even human trafficking.

In the Indian Ocean, off the remote Saya de Malha bank, the refrigerated cargo vessel (reefer) Leelawadee was seen with two unidentified likely fishing vessels tied alongside.

Image Captured by DigitalGlobe on Nov. 30, 2016.

Credit: DigitalGlobe © 2017

Ship to ship transfers can be made quickly and covertly on the high seas, leaving law enforcement officials unaware of the passage of illegal cargo in this watery Wild West.

And it’s no small problem: a 2014 study found that up to a third of wild-caught seafood sold in the United States was harvested illegally.

To combat this shadowy business, Global Fishing Watch, is monitoring the world’s fishing fleets by satellites, hoping to cast light on the dark places beyond national borders.

Global Fishing Watch uses Google Cloud technology to publish fishing efforts around the globe using machine learning.

Everyone can help to observe fishing vessel operators which might practice illegal activity from The Global Fishing Watch map.

With Indonesian Government, Global Fishing Watch overlaps Indonesian Fishing Activity Layer with Global Fishing Activity Layer, which enrich our views and analysis on fishing activities inside and outside Indonesian water.

Everyone can help to observe fishing vessel operators which might practice illegal activity from The Global Fishing Watch map.

With Indonesian Government, Global Fishing Watch overlaps Indonesian Fishing Activity Layer with Global Fishing Activity Layer, which enrich our views and analysis on fishing activities inside and outside Indonesian water.

Global Fishing Watch monitors the positions of boats by tracking the broadcasts from their onboard automated identification system (AIS) transponders.

All passenger ships and vessels larger than 300 gross tonnage are required by the International Maritime Organization to transmit their position.

The system’s main purpose is to reduce the likelihood of collisions between ships, but Global Fishing Watch analysts found they can follow a vessel, decipher its fishing activity, and see where it meets other ships.

The Hai Feng 648 is with an unidentified fishing vessel off the coast of Argentina.

There is a large mostly Chinese squid fleet just beyond the EEZ boundary.

The Hai Feng 648 was previously with the squid fleet at the edge of the Peruvian EEZ and in 2014 took illegally processed catch from the Lafayette into port in Peru.

This image was acquired on Nov. 30, 2016.

Credit: DigitalGlobe © 2017

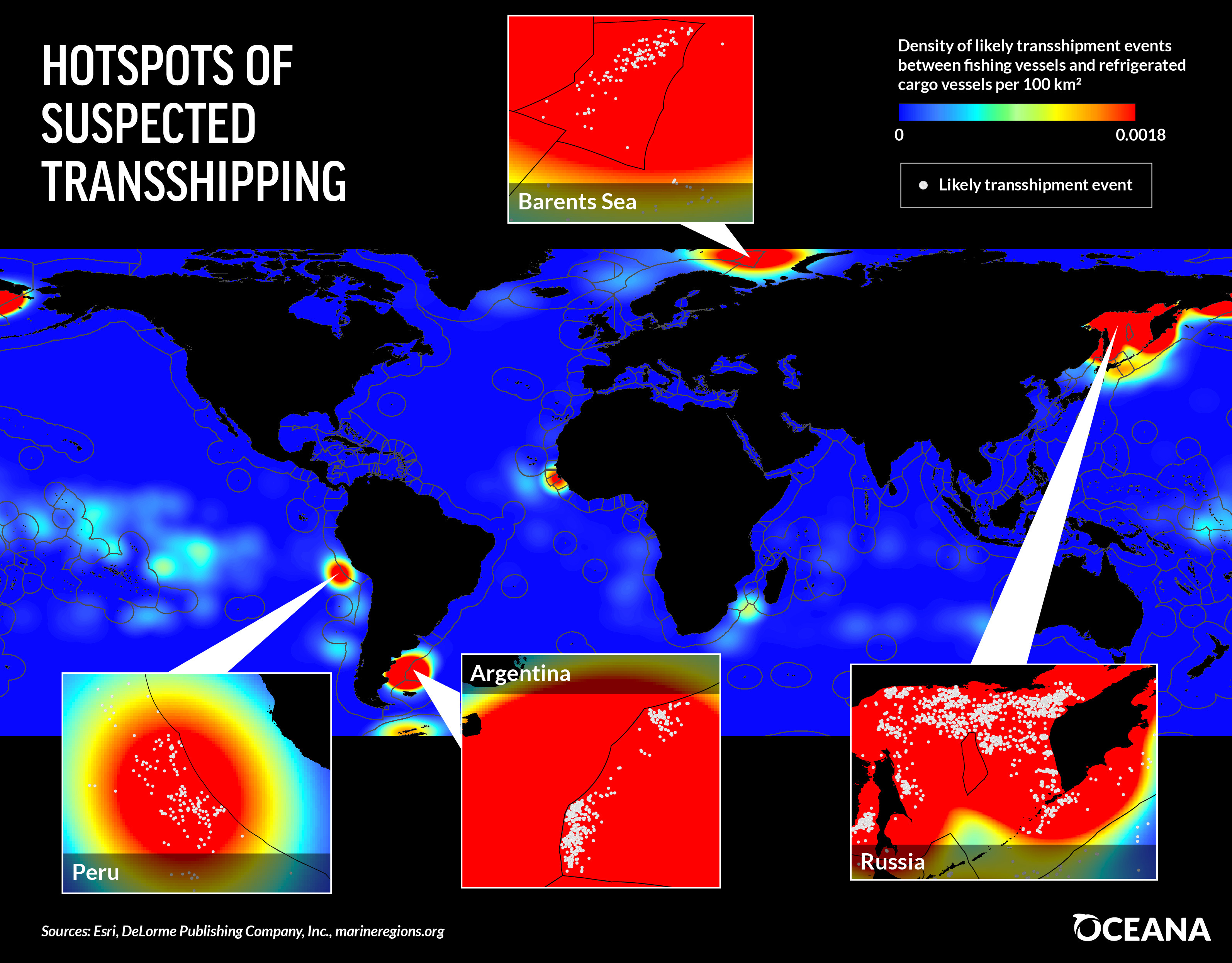

With data from AIS and other satellite tracking systems, the team has created a global map of transshipping activity.

They’ve found that ships cluster outside the boundaries of exclusive economic zones—areas where marine resources are regulated—raising suspicions that the transshipments are associated with illegal fishing.

From 2012 to 2016 researchers identified 5,000 likely cases of transshipment—meetings between fishing vessels and reefers.

They also found an additional 86,000 cases where two reefers met at sea, which may also indicate smuggling.

Despite the extensive vessel tracking, the team can’t say for sure what ships like the American Eagle are up to.

“We may be talking about the issue of transshipment, but what we’re detecting really are what we call vessel rendezvous,” says Nathan Miller, a data scientist with Global Fishing Watch.

“These are two vessels that get close to each other and potentially meet. We don’t even know if they actually meet—all we can detect is they get very, very close together for an extended period of time.”

Global Fishing Watch Reveals a Fisheries Management Success in the Phoenix Islands (Kiribati)

The best they can do, says Bjorn Bergman, a data analyst with the project, is provide the data for authorities to dig into further.

Recently, Global Fishing Watch data was passed to Ecuadorian authorities looking into the transportation of an illegal shark catch near the Galapagos Islands.

“The high seas present a big challenge because that’s where most of the slavery and much of the illegal fishing is, so [Global Fishing Watch] is fantastic to have,” says Daniel Pauly, a fisheries scientist at the University of British Columbia.

“This gives additional weapons to hard-pressed authorities in various countries.”

All of Global Fishing Watch’s data is publicly available on their website, where it’s posted just days after the signals are received.

Automated notifications available through the website can help port authorities, marine conservationists, and other interested parties monitor specific regions for suspicious behavior.

The data is also valuable to companies that want to tell consumers where their seafood comes from.

“Everything that we’re doing … is really about transparency,” says Miller.

“That’s going to be the way in which positive change happens.”

Links :

- Phys : Hidden no more: First-ever global view of transshipment in commercial fishing industry

- UCN : Oceana: 50% of suspected global transshipping events in Russian waters

- Oceana : Report on transshipping

- Francisco Blaha blog : Inroads into illegal transhipments analysis

- GeoGarage blog : The fishing wars are coming / Getting serious about overfishing / How satellite technology is helping to ...

No comments:

Post a Comment