New research arried out in June 2018 to try to find the Cordelière, a flagship of the Franco-Breton fleet, missing at sea, during a battle against the English in 1512... !

500 years later, maritime history enthusiasts, in partnership with the Brittany region, still hope to find the wreck of this ship off Brest.

From BBC by Hugh Schofield

The spirit of famed French explorer Jacques Cousteau lives on in a mission to find the wrecks of two warships, one French and one English, that sank 500 years ago off the Brittany port of Brest.

Instead of Cousteau's old minesweeper Calypso, it is the French culture ministry's surveillance ship André Malraux and its doughty crew of scientists and divers.

André Malraux, DRASSM research vessel deploying various electronic detection means on the survey area necessary to characterize anomalies likely to indicate the wrecks sought.

Frédéric Osada / Images Explorations/ DRASSM

Today's adventure: to locate, excavate and eventually raise the wrecks of the Cordelière and the Regent - two behemoths of the Tudor seas that sank together in the Battle of Saint-Mathieu in 1512.

And filling the Cousteau role is Michel L'Hour, marine archaeologist extraordinaire and veteran of a thousand missions to explore France's underwater heritage.

"I have been obsessed with finding these ships for 40 years," he says, ruddy-faced and bearded like any proper sea-dog.

"I am not so young any more, and I think this may be my last mission.

If I can locate the ships, then leave them to my colleagues to excavate, I will be a happy man."

After initial unsuccessful searches between 1996 and 2001, a new three-week campaign will therefore begin around 20 June in an area of 25 km2 between the 'goulet de Brest' and Point Saint-Mathieu, in waters up to 40 metres deep.

visualization of the area with the GeoGarage platform (SHOM chart)

How the two ships were sunk

For the French, or rather for the people of Brittany, the Cordelière has mythic status.

She was the flagship of the duchy's last independent ruler and revered heroine, the Duchess Anne.

And she was captained up until the moment of sinking (and his death) by another Breton hero, Hervé de Portzmoguer, a kind of patriot-corsair.

His Frenchified name Primauguet is still given to vessels of the French navy to this day.

But the English have a hand in this tale too.

The André Malraux's crew scour the ocean floor with remote-controlled vehicles

The Regent was, in its day, every bit as important as its sister ship the Mary Rose, which was famously raised from the Solent 36 years ago and is now on display in Portsmouth.

If anything, the Regent was the bigger ship.

And if Henry VIII's Mary Rose is anything to go by, then this would be a stupendous find indeed.

The trouble is no-one knows exactly where the Battle of Saint-Mathieu took place.

It was during one of the lesser-known wars between England and an alliance of France and a still-independent Brittany.

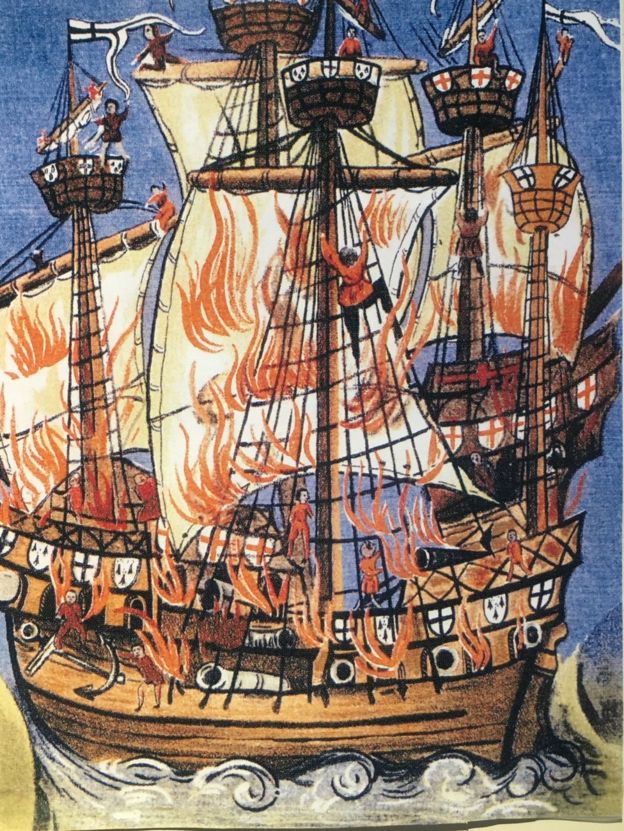

Hundreds died as the two ships caught fire and went down together

Contemporary picture of the Breton Marie-la-Cordelièreand the English Regent flagships ablaze.

The Cordelière flies the Kroaz Du, whilst the Regent flies St. George's Cross

On 10 August 1512, the Franco-Breton fleet was at anchor off Brest when it sighted the approaching English.Contemporary picture of the Breton Marie-la-Cordelièreand the English Regent flagships ablaze.

The Cordelière flies the Kroaz Du, whilst the Regent flies St. George's Cross

Most of the French ships made haste to get to safety through the mouth of the inner bay of Brest, a passage known as the goulet.

But the Cordelière and two other ships stayed to fight off the attack.

Brest Museum

The Regent bore down on the Cordelière and for two or three hours there was close-quarters fighting.

But then, and no-one knows why, it all ended with a massive explosion.

The two ships, entangled in battle, sank together to the bottom.

Hundreds died.

The simultaneous destruction of the Cordelière and the Regent

depicted by Pierre-Julien Gilbert

With backing from the French government, the Brittany region, universities and industry, Michel L'Hour has assembled a multidisciplinary team to find what he knows must be down there somewhere.

Tides and currents have been recalculated.

Previous efforts had failed to spot that the calendar changed in 1582.

Naval charts of the sea floor have been re-examined.

Historians are looking through the few contemporary accounts of the battle, and the search is on for clues from parish and other archives.

Christophe Cerino, of Brittany-South University, says diplomatic records in the UK will be a particular focus.

"We know that several hundred Englishmen were on the Regent, and many were of noble families.

After the battle their bodies will have washed up somewhere on the coast and been given burial," he says.

Research is based on the scant records available and the team is searching for more

"Somewhere in the archives there are bound to be requests from noble families asking for the repatriation of these bodies.

Those requests will contain names of places and parishes.

"Knowing where the bodies washed up, and the state of the currents, we may get a clearer picture where the battle took place."

Close, but no warship

For now Mr L'Hour is working on the theory that the French fleet was anchored near the goulet on the southern side of the outer bay, near the village of Camaret-sur-Mer.

This is based on a contemporary report that it was sheltering from a southerly wind, or auster.

The battle, he thinks, must have taken place in waters to the north of Camaret.

So that is where the André Malraux is now in a back-and-forth combing operation, dragging an array of sonar and magnetic detectors.

An undersea robot sends back video, and divers are ready to explore any find.

Michel L'Hour (director of DRASSM) Olivia Hulot, co-director of the Cordelière Project, Philippe Alain, product manager engineer at IXBlue, a partner in the project, and Luc Jaulin, professor of robotics at the ENSTA-Bretagne engineering school, facing control screens during the acquisition of prospecting data.

Photo credit: Frédéric Osada / Images Explorations/ DRASSM

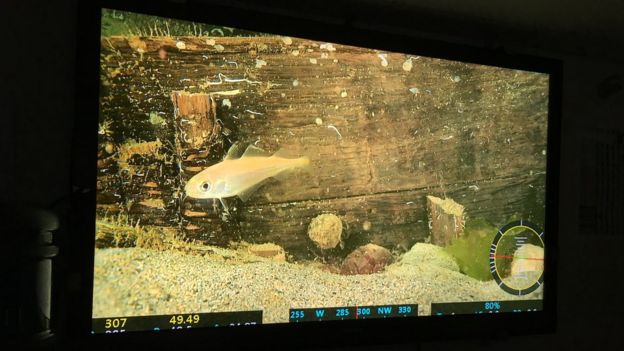

Video footage from the unmanned vehicles is pored over by the team back in the control room

In the operations room, the Cousteau-esque motif holds truer than ever, as the faithful team in identical Cordelière T-shirts (many have been with Michel L'Hour for years) pore over the incoming video and puzzle over recovered pieces of ceramic.

In fact, within the first days there has already been an interesting discovery.

A wreck has been located that is in the right zone.

It is big, and Mr L'Hour can tell from its clinker-built construction (with overlapping planks) that it is from the 15th or 16th Century.

At one point it even looks like there might be two wrecks lying together, which would be a clincher.

A fascinating discovery - but not the one the team was hunting for

But, alas, doubts set in.

If this is a warship, where are the cannon?

There are apparently none, which means it is probably only a commercial ship.

An important find, but not the one they were looking for.

Michel L'Hour is convinced that with all the technology now available the wrecks of the Cordelière and the Regent will eventually be found.

And afterwards who knows?

The dream is of a museum in Brest.

As for the Cousteau comparison, Mr L'Hour - who knew him - is bemused.

"You know that Cousteau was a hopeless archaeologist.

At one of his excavations in the Mediterranean, he completely failed to spot that he was dealing with not one shipwreck but two, one lying on top of the other.

"It was because of the mess he made, that the ministry created our outfit - the first ever government-funded undersea archaeological survey ship.

"But the team, the camaraderie, the seamanship - that I would be proud to share."

The hunt goes on.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment