A rendering of the Floating Island Project in French Polynesia.

Blue Frontiers will build and operate the islands, with the goal of building about a dozen by 2020, including homes, hotels, offices and restaurants, at a cost of about $60 million.

CreditBlue Frontier

From New York Times by David GellesIt is an idea at once audacious and simplistic, a seeming impossibility that is now technologically within reach: cities floating in international waters — independent, self-sustaining nation-states at sea.

Long the stuff of science fiction, so-called “seasteading” has in recent years matured from pure fantasy into something approaching reality, and there are now companies, academics, architects and even a government working together on a prototype by 2020.

Seasteading is accelerating.

News reports can't keep up and frankly don't have a clue.

Want the real story?

Want to know who, why, and how?

Meet some of the leading seasteaders making it happen.

It's even more exciting than you think.

Joe Quirk is solely responsible for this video's content, especially the crazy stuff at the end.

At the center of the effort is the Seasteading Institute, a nonprofit organization based in San Francisco.

Founded in 2008, the group has spent about a decade trying to convince the public that seasteading is not an entirely crazy idea.

That has not always been easy.

At times, the story of the seasteading movement seems to lapse into self parody.

Burning Man gatherings in the Nevada desert are an inspiration, while references to the Kevin Costner film “Waterworld” are inevitable.

The project is being partially funded by an initial coin offering, a new concept sweeping Silicon Valley and Wall Street in which money can be raised by creating and selling virtual currency.

And yet in 2017, with sea levels rising because of climate change and established political orders around the world teetering under the strains of populism, seasteading can seem not just practical, but downright appealing.

A fully autonomous floating city was once just a libertarian fantasy,

but is now just a few years shy of becoming reality.

Earlier this year, the government of French Polynesia agreed to let the Seasteading Institute begin testing in its waters.

Construction could begin soon, and the first floating buildings — the nucleus of a city — might be inhabitable in just a few years.

“If you could have a floating city, it would essentially be a start-up country,” said Joe Quirk, president of the Seasteading Institute.

“We can create a huge diversity of governments for a huge diversity of people.”

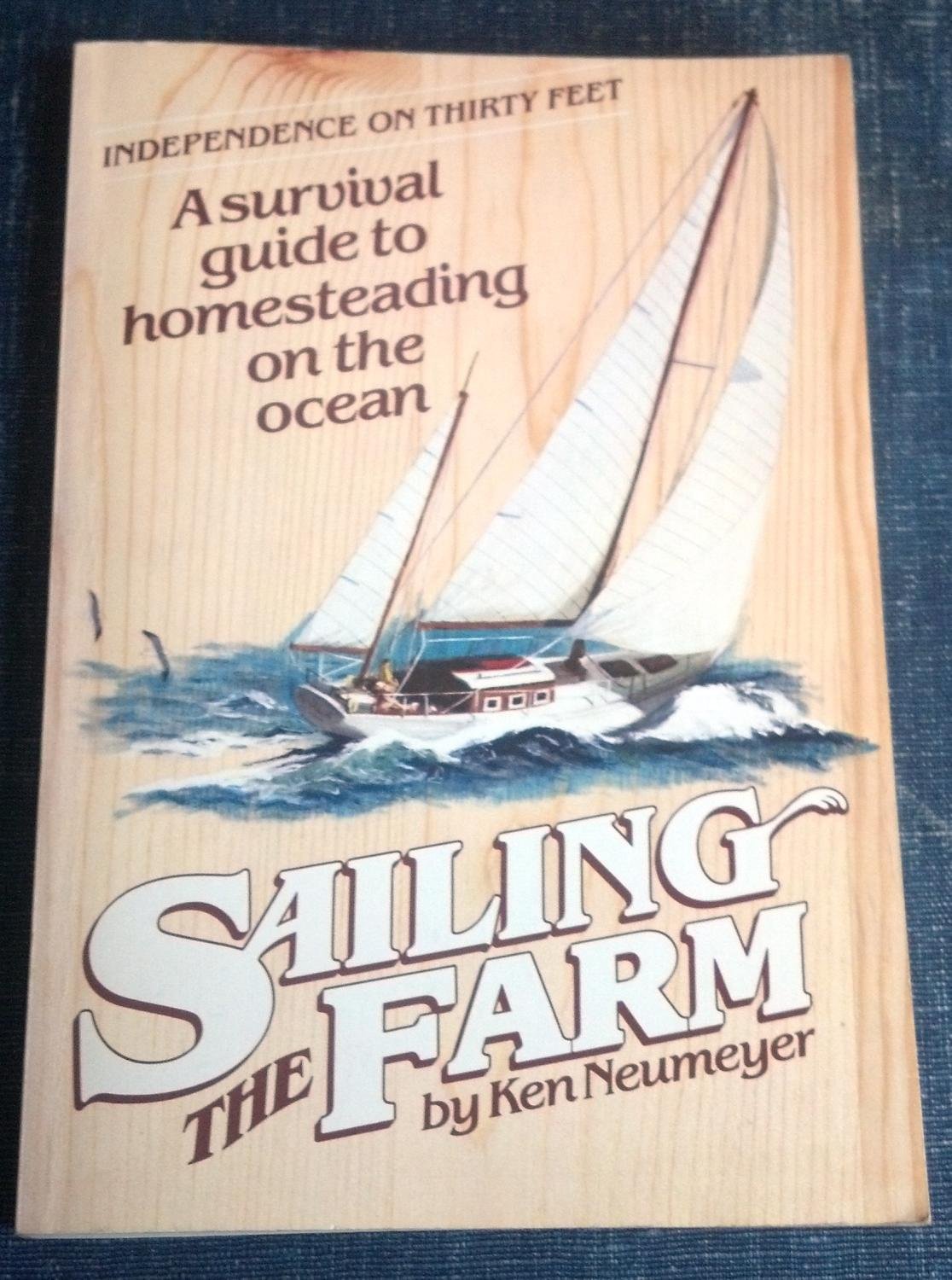

The term seasteading has been around since at least 1981, when the avid sailor Ken Neumeyer wrote a book, “Sailing the Farm,” that discussed living sustainably aboard a sailboat.

Two decades later, the idea attracted the attention of Patri Friedman, the grandson of the economist Milton Friedman, who seized on the notion.

Mr. Friedman, a freethinker who had founded “intentional communities” while in college, was living in Silicon Valley at the time and was inspired to think big.

So in 2008 he quit his job at Google and co-founded the Seasteading Institute with seed funding from Peter Thiel, the libertarian billionaire.

In a 2009 essay, Mr. Thiel described seasteading as a long shot, but one worth taking.

“Between cyberspace and outer space lies the possibility of settling the oceans,” he wrote.

The investment from Mr. Thiel generated a flurry of media attention, but for several years after its founding, the Seasteading Institute did not amount to much.

A prototype planned for San Francisco Bay in 2010 never materialized, and seasteading became a punch line to jokes about the techno-utopian fantasies gone awry, even becoming a plotline in the HBO series “Silicon Valley.”

But over the years, the core idea behind seasteading — that a floating city in international waters might give people a chance to redesign society and government — steadily attracted more adherents.

In 2011, Mr. Quirk, an author, was at Burning Man when he first heard about seasteading.

He was intrigued by the idea and spent the next year learning about the concept.

Based on designs by DeltaSync, a Dutch engineering firm specializing on floating urbanization, this video by Roark3D at Fort Galt illuminates our plan for the Floating City Project, the first floating city with significant political autonomy.

For Mr. Quirk, Burning Man, where innovators gather, was not just his introduction to seasteading.

It was a model for the kind of society that seasteading might enable.

“Anyone who goes to Burning Man multiple times become fascinated by the way that rules don’t observe their usual parameters,” he said.

The next year, he was back at Burning Man speaking about seasteading in a geodesic dome.

Soon after that, he became involved with the Seasteading Institute, took over as president and, with Mr. Friedman, wrote “Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore The Environment, Enrich The Poor, Cure The Sick and Liberate Humanity From Politicians.”

Seasteading is more than a fanciful hobby to Mr. Quirk and others involved in the effort.

It is, in their minds, an opportunity to rewrite the rules that govern society.

“Governments just don’t get better,” Mr. Quirk said.

“They’re stuck in previous centuries.

That’s because land incentivizes a violent monopoly to control it.”

No land, no more conflict, the thinking goes.

Even if the Seasteading Institute is able to start a handful of sustainable structures, there’s no guarantee that a utopian community will flourish.

People fight about much more than land, of course, and pirates have emerged as a menace in certain regions.

And though maritime law suggests that seasteading may have a sound legal basis, it is impossible to know how real governments might respond to new neighbors floating offshore.

Mr. Quirk and his team are focusing on their Floating Island Project in French Polynesia.

The government is creating what is effectively a special economic zone for the Seasteading Institute to experiment in and has offered 100 acres of beachfront where the group can operate.

Mr. Quirk and his collaborators created a new company, Blue Frontiers, which will build and operate the floating islands in French Polynesia.

The goal is to build about a dozen structures by 2020, including homes, hotels, offices and restaurants, at a cost of about $60 million.

To fund the construction, the team is working on an initial coin offering.

If all goes as planned, the structures will feature living roofs, use local wood, bamboo and coconut fiber, and recycled metal and plastic.

“I want to see floating cities by 2050, thousands of them hopefully, each of them offering different ways of governance,” Mr. Quirk said.

“The more people moving among them, the more choices we’ll have and the more likely it is we can have peace, prosperity and innovation.”

Links :

- The Independant : World's first floating city to be built off the coast of French Polynesia by 2020

- DailyMail : Billionaire Barry Diller revives ambitious plans for $250m floating island park in New York City after he spiked it due to rising costs and legal challenges

- NYTimes : As Climate Change Accelerates, Floating Cities Look Like Less of a Pipe Dream

- The Guardian : Seasteading: tech leaders' plans for floating city trouble French Polynesians

- Reason : 20,000 Nations Above the Sea (2009)

- GeoGarage blog : Has the time come for floating cities? / Freedom Ship concept : How floating cities ... / Ocean living: A step closer to reality? / This floating platform could filter the ... / ‘I rule my own ocean micronation’ /As seas rise, future floats / Artificial island could be solution for ... / A floating artificial reef would let you ... /

No comments:

Post a Comment