From The Atlantic by Hannah Hoag

A consortium of countries are meeting in Iceland, where they hope to strike a deal that protects the newly accessible ecosystem.

The Arctic Ocean has long been the least accessible of the world’s major oceans.

But as climate change warms the Arctic twice as fast as anywhere else, the thick sea ice that once made it so forbidding is now beating a hasty retreat.

Since 1979, when scientists began using satellites to track changes in the Arctic sea-ice expanse, its average summertime volume has dropped 75 percent from 4,000 cubic miles to 1,000 cubic miles.

By September, the Arctic Ocean will have swapped nearly 4 million square miles of ice for open ocean.

This accelerated transformation has troubled scientists, conservationists and government officials who are anxious about the fate of the fish that may live in these waters—and for the entire ecosystem itself.

At the center of the Arctic Ocean is a 1.1 million square-mile “donut hole,” surrounded by Canada, the Danish territory of Greenland, Norway, Russia and the United States.

The donut hole does not fall under any country’s jurisdiction, and it may well be the last unexploited fishery on Earth.

According to international law, anyone could fish these newly opening high seas, if they desired, and thanks to the retreating ice, they may soon have their chance.

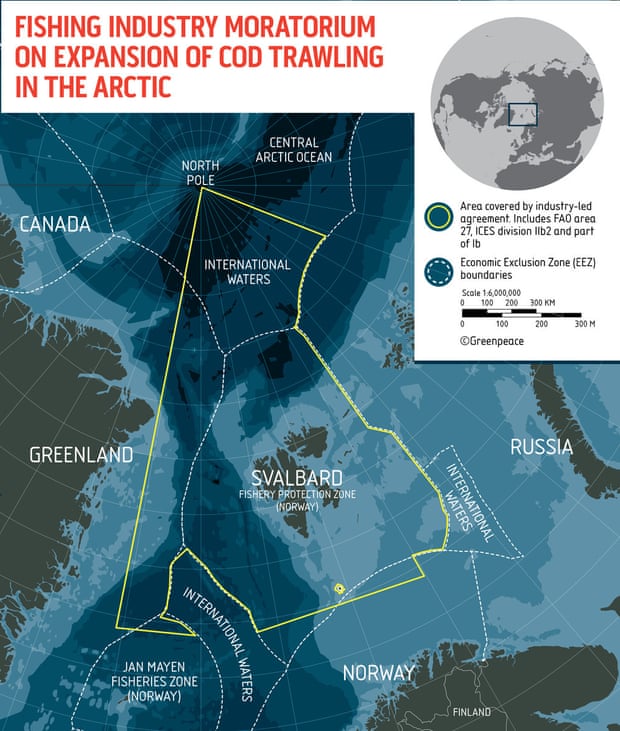

Map of the area of northern Barents Sea including the waters around Svalbard where some of the world’s largest seafood and fishing companies have committed not to expand their search for cod into.

Image : Greenpeace

“It’s my hope that we will actually bring this home, find some compromises on the key issues and produce an agreement that everyone can go ahead and sign,” says Ambassador David Balton, the deputy assistant secretary for Oceans and Fisheries at the U.S. Department of State, who is chairing the talks.

Baffin Fisheries' MV Sivulliq

The agreement aims to avoid the tragedy that occurred in the Bering Sea in the 1980s.

At the time, the U.S. and the Soviet Union fished for pollock within their respective waters.

Almost no one believed there were fish—or foreign fleets—in the international waters between them, says David Benton, a retired fisheries manager from Alaska and a member of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission.

Map of temperature anomalies from average during February 2017

credit NASA

A pair of Alaskan fishermen who thought otherwise chartered an airplane to fly over the donut hole and spotted close to 100 working vessels.

At its height, fishing fleets from Japan, China, Poland, South Korea and others were drawing more than a million of tons of pollock from the waters annually.

“It wasn’t illegal fishing because it was international waters,” says Benton, who is advising the U.S. delegation. But it was unregulated.

A fishing boat cruises in the Ilulissat fjord, on Greenland's western coast.

An international treaty was quickly negotiated, but it was too late.

By the early 1990s, the pollock stock had collapsed.

Twenty-five years later it has still not recovered.

Compared with the donut hole in the Bering Sea, which clocks in close to 50,000 square miles, the one in the Arctic Ocean is enormous.

“There has been a lot of discussion about shipping in the Arctic Ocean, but in my experience the first people into an ocean are the fishermen,” says Peter Harrison, an Arctic policy and fisheries expert at Queen’s University in Canada, and a former deputy minister of Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Lately, as much as 42 percent of the central Arctic Ocean is open water during the summer months.

Links :

- The Guardian : Major fishing deal offers protection to Arctic waters

- Arctic : Federal Agency for Fishery: A new organization may be created to regulate Arctic fishing

- ScienceDaily : Acidification of Arctic Ocean may threaten marine life, fishing industry

- Scientific American : Arctic Sea Ice Sets Record-Low Peak for Third Year

No comments:

Post a Comment