Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Where are those shoes you ordered? Check the ocean floor

Maersk Eindhoven / Credit: Shipspotting

From Wired by Aarian Marshall

Since the end of November, this is some of what has sunk to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean: vacuum cleaners; Kate Spade accessories; at least $150,000 of frozen shrimp; and three shipping containers full of children’s clothes.

“If anybody has investments in deep-sea salvage, there's some beautiful product down there,” Richard Westenberger, chief financial officer of the children’s clothing brand Carter’s told a conference recently.

You can blame the weather, a surge in US imports tied to the pandemic, or a phenomenon known as parametric rolling.

All told, at least 2,980 containers have fallen off cargo ships in the Pacific since November, in at least six separate incidents.

That’s more than twice the number of containers lost annually between 2008 and 2019, according to the World Shipping Council.

Shipping companies tend to blame the weather.

Shipping companies tend to blame the weather.

The Maersk Essen, which lost 750 containers while sailing from China to Los Angeles in mid-January, “experienced heavy seas during her North Pacific crossing,” Maersk said in a press statement.

(The company didn’t respond to WIRED’s questions.)

The Maersk Eindhoven experienced “heavy weather” in mid-February that contributed to a shipwide blackout in the middle of a storm; it lost 260 containers.

The ONE Apus lost more than 1,800 containers during high winds and large swells in November, in what's expected to prove one of the costliest losses ever.

Photograph: Buddhika Weerasinghe/Bloomberg/Getty Images

The ONE Apus, bound for the port of Long Beach from southern China, lost more than 1,800 containers during what the company called “gale-force winds and large swells” in November.

That’s expected to prove one of the costliest losses ever.

The tough weather has been exacerbated by rising traffic to the US. US container imports grew 30 percent in December, compared with the same month a year earlier, according to IHS Markit.

“It’s a boom in import cargo beyond anything we've seen before,” says Lars Jensen, the CEO of SeaIntelligence Consulting, which advises clients in the container shipping industry.

That’s led to a shortage of containers, particularly empty containers stuck in North America when they’re needed in Asia.

So it’s possible that shippers have pressed older, well-used containers into service, which are more likely to have defective or corroded lashing or locking mechanisms, says Ian Woods, a marine cargo lawyer and a partner with the firm Clyde & Co.

Then you’ve got tired crews, stretched by the extra work so they’re not able to pack and secure the containers as well as they would if well rested.

“It’s a boom in import cargo beyond anything we've seen before.”

Lars Jensen, CEO, SeaIntelligence Consulting

Plus, the ships are packed. “Not only do we have large vessels, bad weather, but we have, in many cases, vessels that are chock-a-block full,” says Jensen, the shipping consultant.

A full container ship can be the length of four football fields, able to carry as many as 24,000 20-foot-long containers stacked five or six high.

These are more likely to experience a phenomenon called parametric rolling, a rare but scary violent motion that can send blocks of containers tumbling to deck—or into the sea.

Data from the space-based analytics company Spire shows the Maersk Eindhoven got caught in bad weather and high waves before losing power—and 260 containers.

Courtesy of Spire

Parametric rolling happens when the time that passes between two adjacent waves suddenly lines up with the natural roll frequency of a ship, something that’s more likely to happen in bad weather.

Adrian Onas, a professor of naval architecture at the Webb Institute, calls this a “heart attack of design”—difficult to detect when it’s beginning, and then devastating.

Onboard, parametric rolling feels like abrupt, terrifying side-to-side movement, which quickly changes from just a few degrees to up to 35 or 40 degrees in each direction.

Parametric rolling is a bigger deal in container ships than other vessels because they’re designed to move goods quickly across the ocean.

As a result, container ships aren’t always that stable, says Onas.

Add six stories of containers to 35-degree rolling motions, and you get extremely fast acceleration at the top of the container stack.

Containers aren’t secured to withstand such forces, Onas says.

So they begin to fall.

In general, parametric rolling is rare.

But a full container ship is more likely to experience the phenomenon, says Onas—which means that right now, the conditions are ripe.

Parametric rolling is like a “heart attack of design.”

Adrian Onas, professor of naval architecture, Webb Institute

Parametric rolling is like a “heart attack of design.”

Adrian Onas, professor of naval architecture, Webb Institute

Designing a ship to be less susceptible to the rolling, and training crews to interrupt the motion, would cost the industry in time and money; the International Maritime Organization, which is in charge of creating seaworthiness standards, has been considering the issue.

It will likely be months, and maybe even years, before anyone knows exactly what happened to the container ships in the Pacific.

“The investigation process is still underway and will be a long process,” says Michael Hird, the director of the recoveries and cargo casualty department at the marine insurer WK Webster, which is involved in many of the recent cargo loss incidents.

Some cases will likely lead to lawsuits, he says.

He declined to comment further.

In the meantime, engineers will pore over every bit of data about the incidents, with lawyers—for the shipping lines, the insurance companies, and the companies whose goods were lost—looking over their shoulders.

Regulators should be interested, too, says Jensen, the consultant. Might some rules about securing containers to ships need reevaluating?

“You’ll have a lot of people keenly interested in why this is happening,” he says.

What else might a deep-sea diver find?

A maritime trade analyst from Freightwaves, the logistics and supply chain data firm, suggested to a trade publication recently that other companies that suffered losses included Ikea, Williams-Sonoma, Adidas, Puma, and the children’s toy company Hasbro.

Monday, January 30, 2023

The legal implications of the 2022 Canada-Denmark/Greenland Agreement on Hans Island (Tartupaluk) for the Inuit peoples of Greenland and Nunavut

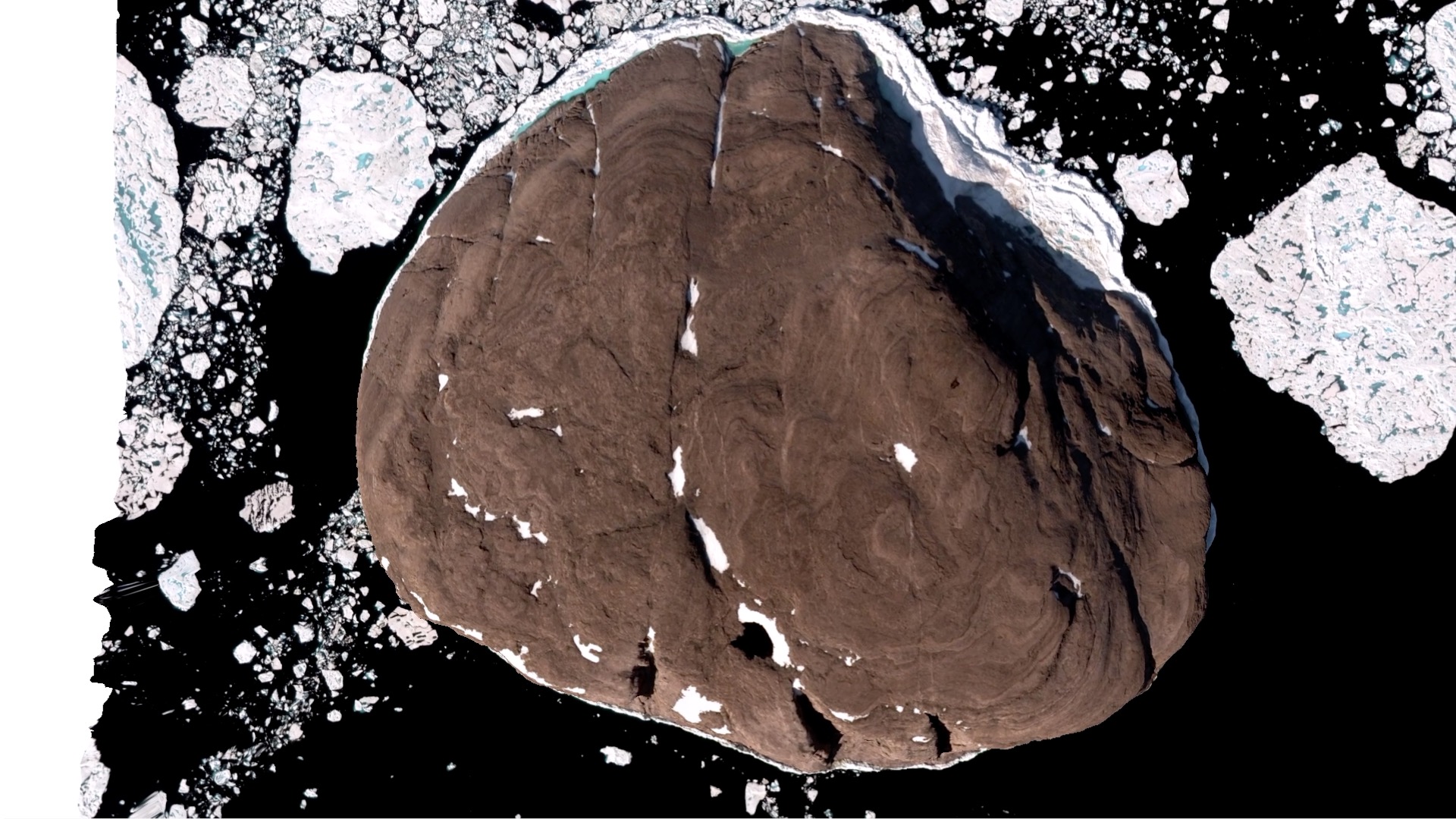

Hans Island (Tartupaluk) looking toward the west with Ellesmere Island in the background.

The newly established international border runs approximately from the top left to the lower right, with

Denmark/Greenland on the left and Canada on the right. In 2018 a expedition from Denmark and Greenland, including ArcticToday contributor Martin Breum, traveled to Hans Island in the Kennedy Channel between Greenland and Nunavut, Canada. (Copyright 2018 Martin Breum)

The newly established international border runs approximately from the top left to the lower right, with

Denmark/Greenland on the left and Canada on the right. In 2018 a expedition from Denmark and Greenland, including ArcticToday contributor Martin Breum, traveled to Hans Island in the Kennedy Channel between Greenland and Nunavut, Canada. (Copyright 2018 Martin Breum)

From The Arctic Institute by Apostolos Tsiouvalas & Endaew Lijalem Enyew

On June 14, 2022, Mélanie Joly, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada, Jeppe Kofod, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, along with Múte Bourup Egede, Prime Minister of Greenland, signed an Agreement in Ottawa resolving outstanding boundary issues between the sovereign states of Canada and the Kingdom of Denmark.

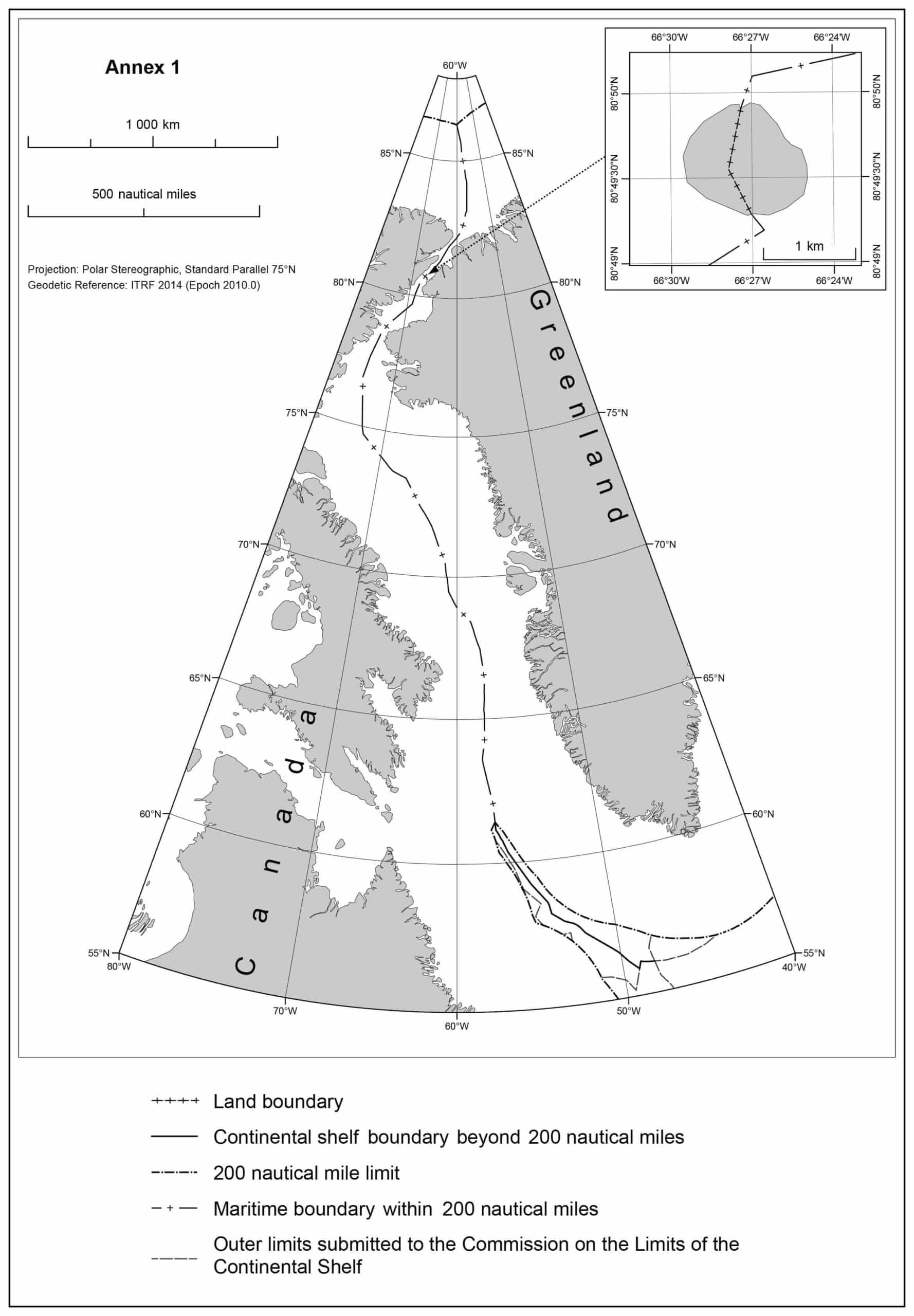

The new Agreement determines the maritime boundary on the continental shelf within 200 nautical miles, including the Lincoln Sea, the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles in the Labrador Sea, and resolves a nearly 50-year-old dispute over the limestone Hans Island (also known as Tartupaluk) covering 1.3 km², situated in the Kennedy Channel portion of Nares Strait – about 18 km to the coasts of Ellesmere Island and Northwest Greenland respectively.

Although uninhabited, Tartupaluk has historically been significant both to the Inughuit of Avanersuaq in Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) and to the Inuit of Nunavut, Canada.

As such, the 2022 Agreement constitutes a historic milestone for the future of Inuit rights in the region.

This blog post explores the legal implications of the Agreement on Tartupaluk for the traditional (fishing and hunting) rights of the Inuit Peoples of Greenland and Nunavut.

The post first provides an overview of the background of the dispute and the content of the 2022 Agreement.

It deals with the implication of the Agreement on the traditional rights of the Inuit people, followed by an examination of whether the recognition of Inuit rights under the Agreement is consistent with international law.

Although uninhabited, Tartupaluk has historically been significant both to the Inughuit of Avanersuaq in Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) and to the Inuit of Nunavut, Canada.

As such, the 2022 Agreement constitutes a historic milestone for the future of Inuit rights in the region.

This blog post explores the legal implications of the Agreement on Tartupaluk for the traditional (fishing and hunting) rights of the Inuit Peoples of Greenland and Nunavut.

The post first provides an overview of the background of the dispute and the content of the 2022 Agreement.

It deals with the implication of the Agreement on the traditional rights of the Inuit people, followed by an examination of whether the recognition of Inuit rights under the Agreement is consistent with international law.

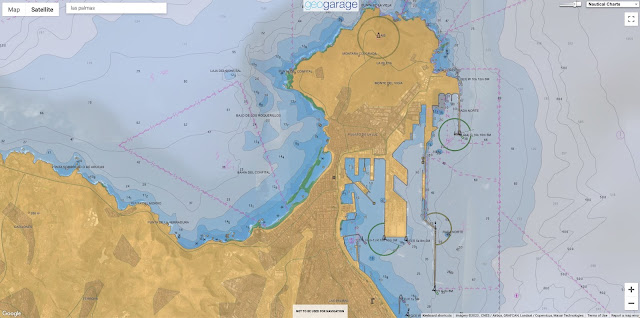

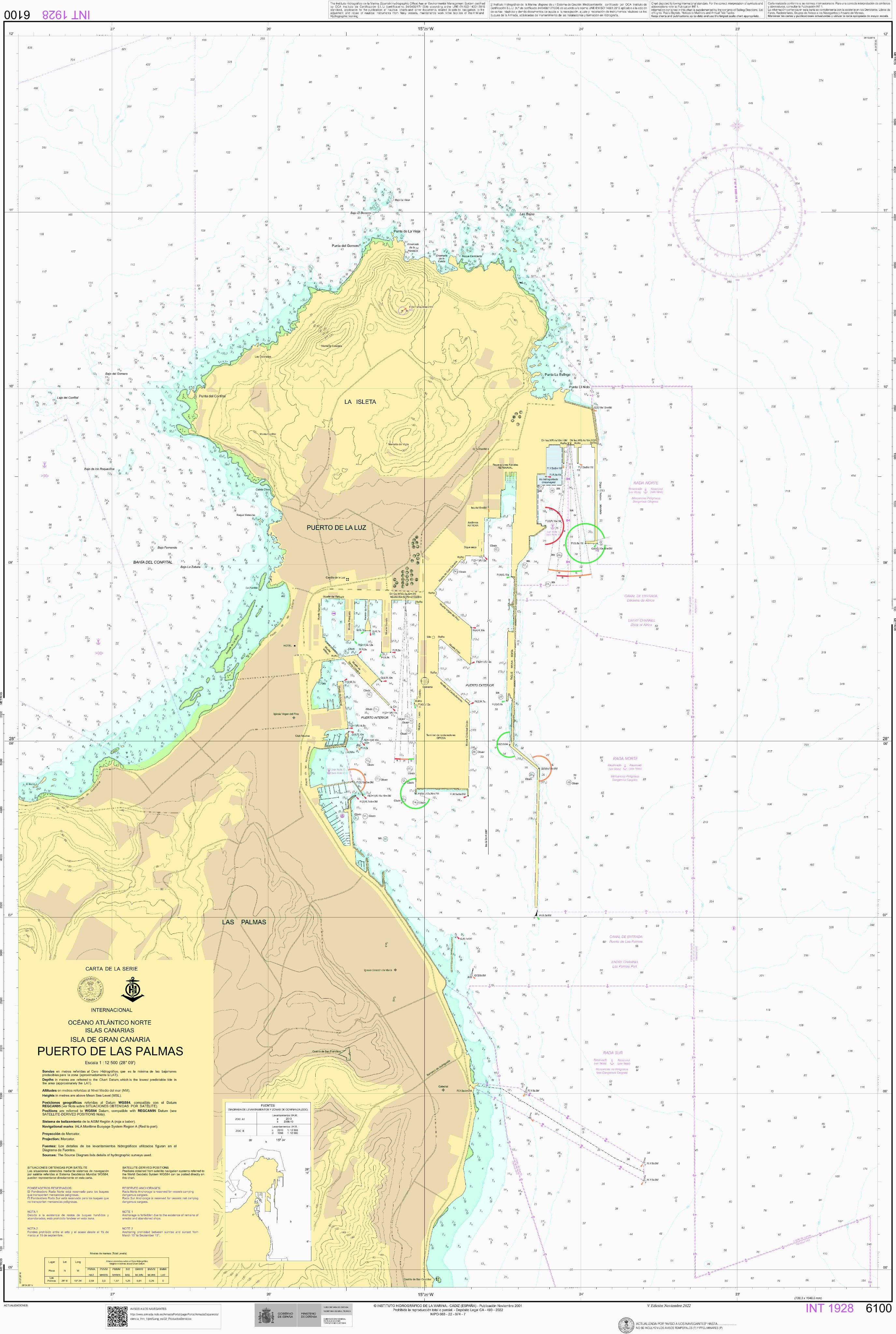

Localization of the Hans island in the GeoGarage platform (DGA nautical raster chart)

A satellite image of Hans Island shows a prominent rift that runs near the center of the Island. (Denmark Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Background of the Dispute

Tartupaluk – which means ‘kidney’ in the local Inuktun language – was unknown to the rest of the world until the 19th century, when European and American explorers attempted to first map the Arctic high north.

Several of these endeavors were guided by local Inuit hunters, such as Suersaq, a Northwest Greenlander who assisted on several missions.

Suersaq, who was later nicknamed Hans Hendrik by expedition members, joined American Charles Francis Hall’s Polaris expedition which was the first ever mapped Tartupaluk in 1872.

Tartupaluk – which means ‘kidney’ in the local Inuktun language – was unknown to the rest of the world until the 19th century, when European and American explorers attempted to first map the Arctic high north.

Several of these endeavors were guided by local Inuit hunters, such as Suersaq, a Northwest Greenlander who assisted on several missions.

Suersaq, who was later nicknamed Hans Hendrik by expedition members, joined American Charles Francis Hall’s Polaris expedition which was the first ever mapped Tartupaluk in 1872.

Expedition notes reveal that when the tiny limestone island was first mapped, it was named in honor of Hans Hendrik.

Eight years after the initial mapping of the island, on 1 September 1880, Canada established sovereignty over all Britain’s former Arctic possessions including Ellesmere Island, based on the British Adjacent Territories Order.

Fifty years after – following unsuccessful US claims in the northern portions of Greenland – with a 1933 decision of the Permanent Court of International Justice, Denmark also extended its sovereignty over the entirety of the island of Greenland and has maintained it as a semi-autonomous possession ever since.

The dispute over Hans Island began about 50 years ago when Canada and Denmark initiated negotiations to demarcate a 1,450-nm-long continental shelf boundary between Canada and Greenland without reaching an agreement concerning the title over Hans Island which lies midway between the two States.

Thus, the 1973 Delimitation Agreement deliberately left without a determined boundary the area between the geodetic points 122 and 123 where Hans Island is located.

The decades following the 1973 delimitation treaty triggered a rather political pseudo-confrontation regarding sovereignty over the island,4) with Canada and Denmark provoking each other by planting flags on the island, pursuing annual military visits, and exchanging bottles of whiskey and schnapps.

Fifty years after – following unsuccessful US claims in the northern portions of Greenland – with a 1933 decision of the Permanent Court of International Justice, Denmark also extended its sovereignty over the entirety of the island of Greenland and has maintained it as a semi-autonomous possession ever since.

The dispute over Hans Island began about 50 years ago when Canada and Denmark initiated negotiations to demarcate a 1,450-nm-long continental shelf boundary between Canada and Greenland without reaching an agreement concerning the title over Hans Island which lies midway between the two States.

Thus, the 1973 Delimitation Agreement deliberately left without a determined boundary the area between the geodetic points 122 and 123 where Hans Island is located.

The decades following the 1973 delimitation treaty triggered a rather political pseudo-confrontation regarding sovereignty over the island,4) with Canada and Denmark provoking each other by planting flags on the island, pursuing annual military visits, and exchanging bottles of whiskey and schnapps.

Within these political debates, the Danish side often invoked the historical Inughuit presence on the island, mainly through the Danish Minister for Greenland, a post which was laid down in 1987.

6) Similar arguments have been also echoed by the Canadian side, which often attributes Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic to the historical Inuit use and occupancy of the entire Canadian archipelago.

6) Similar arguments have been also echoed by the Canadian side, which often attributes Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic to the historical Inuit use and occupancy of the entire Canadian archipelago.

Canada-Denmark/Greenland Hans Island boundary agreed to on June 14, 2022.

The 2022 Agreement on Tartupaluk

To resolve the pending border questions, the two close NATO allies convened a joint task force in 2018, which eventually led to the 2022 Agreement.

The Agreement ended the long-standing dispute over the legal status of the island and signaled the establishment of the first land border between Canada and Denmark/Greenland, which was celebrated with the last symbolic exchange of liquor during the negotiations.

Based on the 2022 Agreement, Tartupaluk, which lies within Canada’s territorial sea and Greenland’s EEZ (given that the territorial sea in Greenland is so far limited to 3 nm) will thus be divided along a natural ridge with about 60% of the area being allocated to Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) and the remainder of the area to Canada following the natural gully vertically cutting through the island.

Drawing an equidistance line through the middle of shorelines from both sides is often considered the most convenient way for adjacent sovereign states to determine borders in order to achieve an equitable result, and this was the case for Tartupaluk.

The Agreement further led to a delimitation of the remaining maritime border in the Lincoln and Labrador seas, while the parties agreed that a “practical and workable border-implementation regime” shall be established to manage visitors, tourism and trade across Canada and Denmark’s newest land border.

The Agreement meant the creation of a total of 3,962 km length maritime boundary, which is so far the longest in the world consisting of 179 coordinates.

Implications of the Agreement on Tartupaluk for the Inuit people

The closest existing Inughuit hamlet Siorapaluk in Avanersuaq, North Greenland, lies 349 km (217-mile) south of Tartupaluk and the closest Inuit settlement in Canada, Ausuittuq (Grisefjord), lies 603 km on the southwest.

The island was used by the Inughuit Greenlanders for centuries as a staging point when hunting polar bears and other game, while until recently the island’s cliffs served as observatory spots in identifying marine mammals on the surrounding sea-ice.

Implications of the Agreement on Tartupaluk for the Inuit people

The closest existing Inughuit hamlet Siorapaluk in Avanersuaq, North Greenland, lies 349 km (217-mile) south of Tartupaluk and the closest Inuit settlement in Canada, Ausuittuq (Grisefjord), lies 603 km on the southwest.

The island was used by the Inughuit Greenlanders for centuries as a staging point when hunting polar bears and other game, while until recently the island’s cliffs served as observatory spots in identifying marine mammals on the surrounding sea-ice.

While the direct implications of the Agreement may at first glance seem of a more pragmatic value for the Inughuit of Greenland, whose settlements are geographically located closer to the boundary, the Agreement has undoubtedly far-reaching importance for the Inuit of both sides.

Prior to the conclusion of the Agreement, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) developed and implemented a broad consultation plan for talks with Inuit in Canada to discuss policy and border processing options that will ensure their continued historic and traditional access to Hans Island.

Prior to the conclusion of the Agreement, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) developed and implemented a broad consultation plan for talks with Inuit in Canada to discuss policy and border processing options that will ensure their continued historic and traditional access to Hans Island.

Denmark also pursued consultations with the Inughuit of Northwest Greenland (Municipality of Avannaata).

For a discussion of whether these consultations are in accordance with the commitments of both States under international law.

The Agreement’s provisions further ensured rights for the Inuit of both Nunavut and Greenland to freedom of movement throughout the island for “hunting, fishing and other related cultural, traditional, historic and future activities”.

For a discussion of whether these consultations are in accordance with the commitments of both States under international law.

The Agreement’s provisions further ensured rights for the Inuit of both Nunavut and Greenland to freedom of movement throughout the island for “hunting, fishing and other related cultural, traditional, historic and future activities”.

The premier of Nunavut praised the level of Inuit participation in the negotiations of the Agreement and stated that for Inuit, “lands, waters and ice form a singular homeland…used, crossed and inhabited freely before formal boundaries were created by political jurisdictions”.

Although the establishment of a free movement regime is only applicable to a tiny uninhabited territory of 1.3 km², relatively far from existing Inuit settlements and does not extend to the water/sea-ice surrounding the island, it holds a significant symbolic value for the Inuit of both sides, since it demonstrates the integrity of Inuit traditional areas that extend beyond state-established sovereign borders.

Largely dependent on traversing the sea-ice to hunt birds and marine mammals such as seals, walruses, polar bears and narwhals, the Inuit of the region – predominantly the adjacent Greenlandic Inughuit – were historically living as semi-nomadic peoples, moving between different settlements at certain seasons of the year for hunting purposes and to visit family members.

Largely dependent on traversing the sea-ice to hunt birds and marine mammals such as seals, walruses, polar bears and narwhals, the Inuit of the region – predominantly the adjacent Greenlandic Inughuit – were historically living as semi-nomadic peoples, moving between different settlements at certain seasons of the year for hunting purposes and to visit family members.

In this context, traditional Inughuit hunting grounds extended on Tartupaluk and throughout the entire coast of northwest Greenland, and often included sites over the coast of Umimmaat Nunaat (Ellesmere Island) in Canada.

Although Inughuit hunting mobility patterns have nowadays been decreased in response to political and socioecological changes in the region, the general understanding of seasonal migration is still pertinent to their livelihoods, as many ‘great hunters’ (Piniatorsuaq) still pursue long trips in search of prey.

Despite the Inughuit self-identify as a distinct group of the Kalaallit (Greenlanders), the Kingdom of Denmark accepts the existence of only one Indigenous people, the Inuit of Greenland.

In the court case Hingitaq 53 v. Denmark the Greenlandic government formally declared that the Inughuit “do not constitute a tribal people or a particular Indigenous people within Greenland but are part of the Greenlandic people as a whole”.

Institutionalizing the acknowledgment of the immemorial Inuit use of Tartupaluk may thus manifest a step further towards the ongoing struggle of the Inughuit for recognition as a distinct Indigenous group within Greenland largely connected to Avanersuaq’s particular socio-ecological system.

Maintaining hunting rights and freedom of movement on the entirety of Tartupaluk island for the purpose of traditional activities may further signify a first step towards the acknowledgment of the overall integrity of Inuit territories that extends across the borders of Greenland and Canada and may prompt future negotiations all the way south to Baffin Bay where Inuit presence is much stronger in both sides.

Inuit communities’ subsistence in northern Baffin Bay has always been closely dependent on the adjacent North Water Polynya (Pikialasorsuaq) ecosystem that lies between the two states and constitutes the most biologically productive region northern of the Arctic Circle.

Characterized by impressive migratory patterns of birds and mammals tightly linked to the Polynya’s morphology, Pikialasorsuaq has shaped Inuit activities in the sea/sea-ice for centuries.

To address the future of Pikialasorsuaq in light of a changing Arctic and negotiate an Inuit-led co-management regime for the Polynya, the Inuit Circumpolar Council of Greenland (ICC Greenland) together with the respective department of Canada (ICC Canada) established in January 2016 the Pikialasorsuaq Commission, through a project funded for 3 years.

Despite the Inughuit self-identify as a distinct group of the Kalaallit (Greenlanders), the Kingdom of Denmark accepts the existence of only one Indigenous people, the Inuit of Greenland.

In the court case Hingitaq 53 v. Denmark the Greenlandic government formally declared that the Inughuit “do not constitute a tribal people or a particular Indigenous people within Greenland but are part of the Greenlandic people as a whole”.

Institutionalizing the acknowledgment of the immemorial Inuit use of Tartupaluk may thus manifest a step further towards the ongoing struggle of the Inughuit for recognition as a distinct Indigenous group within Greenland largely connected to Avanersuaq’s particular socio-ecological system.

Maintaining hunting rights and freedom of movement on the entirety of Tartupaluk island for the purpose of traditional activities may further signify a first step towards the acknowledgment of the overall integrity of Inuit territories that extends across the borders of Greenland and Canada and may prompt future negotiations all the way south to Baffin Bay where Inuit presence is much stronger in both sides.

Inuit communities’ subsistence in northern Baffin Bay has always been closely dependent on the adjacent North Water Polynya (Pikialasorsuaq) ecosystem that lies between the two states and constitutes the most biologically productive region northern of the Arctic Circle.

Characterized by impressive migratory patterns of birds and mammals tightly linked to the Polynya’s morphology, Pikialasorsuaq has shaped Inuit activities in the sea/sea-ice for centuries.

To address the future of Pikialasorsuaq in light of a changing Arctic and negotiate an Inuit-led co-management regime for the Polynya, the Inuit Circumpolar Council of Greenland (ICC Greenland) together with the respective department of Canada (ICC Canada) established in January 2016 the Pikialasorsuaq Commission, through a project funded for 3 years.

The Pikialasorsuaq Commission addressed emerging issues pertinent to the region’s people, advocating inter alia for ‘unrestricted’ Inuit movement across and around the Polynya and concluding with three main recommendations for policy makers.

Almost concurrently with the signing of the Tartupaluk Agreement, ICC Greenland entered into a cooperation agreement with Oceans North Kalaallit Nunaat and a task force was established with the aim of promoting the work of the Pikialasorsuaq Commission and ensuring its recommendations are recognized and eventually implemented by the Greenlandic government.

While the implementation phase of Pikialasorsuaq Commission’s work has nowadays started and negotiations on freedom of movement for Inuit to visit friends and family are underway, cross-border hunting for the Inuit of both sides has not yet been established by state law and is nowadays limited to each state’s EEZ and remains strictly controlled by domestic hunting legislations.

While the implementation phase of Pikialasorsuaq Commission’s work has nowadays started and negotiations on freedom of movement for Inuit to visit friends and family are underway, cross-border hunting for the Inuit of both sides has not yet been established by state law and is nowadays limited to each state’s EEZ and remains strictly controlled by domestic hunting legislations.

Is the recognition of the traditional rights of the Inuit peoples over Tartupaluk consistent with international law?

Traditional fishing and hunting rights are rights of artisanal/indigenous coastal communities to trans-maritime-boundary access and exploitation of resources acquired through long usage/ immemorial fishing and hunting practices in a specific area of ocean space.

The material content of traditional fishing and hunting rights is not limited to fishing and hunting practices, but also includes other activities traditionally associated with such practices, such as unimpeded passage from base stations to the traditional fishing and hunting ground, the use of islands for temporary shelter, or for drying and salting of the harvested fish, or for repairing hunting and fishing tools.

Since marine areas are not only economic spaces but also social spaces for Indigenous peoples, traditional fishing and hunting rights also encompass access to such areas to conduct traditional, spiritual, and cultural activities.

The crucial proposition of traditional fishing and hunting rights is the principle of continuity, which posits that allocation/delimitation of a certain marine area under the sovereignty or jurisdiction of a coastal state does not extinguish entitlements of Indigenous peoples based on prior/traditional use.

That is, existing traditions remain undisturbed by the change in the status of the ocean space.

The right of Indigenous peoples to trans-maritime boundary access and utilization of marine resources is recognized under international law, both in international human rights law and the law of the sea.

It is a well-established rule that coastal states are obligated to recognize the human rights of all persons (individuals as well as communities) within their territory or subject to their jurisdiction, irrespective of ‘their nationality or statelessness’.

This implies that relevant human rights norms require a coastal state to respect the traditional fishing and hunting rights of neighboring Indigenous communities conducted within waters under the jurisdiction of such a coastal state.

Article 14(1) of the ILO Convention 169, which protects the rights of nomadic Indigenous communities ‘to use lands [and marine areas] not exclusively occupied by them, but to which they have traditionally had access for their subsistence and traditional activities’, is particularly relevant in this context.

Since marine areas are not only economic spaces but also social spaces for Indigenous peoples, traditional fishing and hunting rights also encompass access to such areas to conduct traditional, spiritual, and cultural activities.

The crucial proposition of traditional fishing and hunting rights is the principle of continuity, which posits that allocation/delimitation of a certain marine area under the sovereignty or jurisdiction of a coastal state does not extinguish entitlements of Indigenous peoples based on prior/traditional use.

That is, existing traditions remain undisturbed by the change in the status of the ocean space.

The right of Indigenous peoples to trans-maritime boundary access and utilization of marine resources is recognized under international law, both in international human rights law and the law of the sea.

It is a well-established rule that coastal states are obligated to recognize the human rights of all persons (individuals as well as communities) within their territory or subject to their jurisdiction, irrespective of ‘their nationality or statelessness’.

This implies that relevant human rights norms require a coastal state to respect the traditional fishing and hunting rights of neighboring Indigenous communities conducted within waters under the jurisdiction of such a coastal state.

Article 14(1) of the ILO Convention 169, which protects the rights of nomadic Indigenous communities ‘to use lands [and marine areas] not exclusively occupied by them, but to which they have traditionally had access for their subsistence and traditional activities’, is particularly relevant in this context.

Article 25 of the UNDRIP, which obliges states to recognize the rights of indigenous peoples to ‘maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual [and cultural] relationship with their traditionally… used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources’ is equally important.

More specifically, Article 32 of the ILO Convention 169 and Article 36(1) of UNDRIP impose obligations on states to recognize cross-border traditional activities.

Article 32 of the ILO Convention 169, to which Denmark is a party, provides that governments: “shall take appropriate measures, including by means of international agreements, to facilitate contacts and cooperation between Indigenous and tribal peoples across borders, including activities in the economic, social, cultural, spiritual and environmental fields”.

Similarly, Article 36(1) of the UNDRIP, which is endorsed both by Canada and Denmark, stipulates that: “Indigenous peoples, in particular those divided by international borders, have the right to maintain and develop contacts, relations and cooperation, including activities for spiritual, cultural, political, economic and social purposes, with their own members as well as other peoples across borders”.

To give effect to the above substantive rights, the coastal state is also required to consult the concerned indigenous communities (or the State of their nationality) before taking measures that may affect their traditional fishing and hunting rights, pursuant to Article 6 of ILO 169 and Articles 18, 19, 32 of the UNDRIP.

The LOSC also recognizes traditional rights in certain maritime zones.

The LOSC explicitly acknowledged traditional fishing rights in archipelagic waters under Article 51(1).

Although the LOSC does not expressly recognize such rights in the territorial sea (TS), international tribunals have characterized traditional fishing rights as ‘vested rights’ falling within the renvoi ‘other rules of international law’ under Article 2(3) of the LOSC (see for example, the South China Sea Arbitration, [808]).

The South China Sea Tribunal further concluded that the ‘attention paid to traditional fishing rights in international law stems from the recognition that traditional livelihoods and cultural patterns are fragilein the face of development and modern ideas of interstate relations and warrant particular protection’.

Article 32 of the ILO Convention 169, to which Denmark is a party, provides that governments: “shall take appropriate measures, including by means of international agreements, to facilitate contacts and cooperation between Indigenous and tribal peoples across borders, including activities in the economic, social, cultural, spiritual and environmental fields”.

Similarly, Article 36(1) of the UNDRIP, which is endorsed both by Canada and Denmark, stipulates that: “Indigenous peoples, in particular those divided by international borders, have the right to maintain and develop contacts, relations and cooperation, including activities for spiritual, cultural, political, economic and social purposes, with their own members as well as other peoples across borders”.

To give effect to the above substantive rights, the coastal state is also required to consult the concerned indigenous communities (or the State of their nationality) before taking measures that may affect their traditional fishing and hunting rights, pursuant to Article 6 of ILO 169 and Articles 18, 19, 32 of the UNDRIP.

The LOSC also recognizes traditional rights in certain maritime zones.

The LOSC explicitly acknowledged traditional fishing rights in archipelagic waters under Article 51(1).

Although the LOSC does not expressly recognize such rights in the territorial sea (TS), international tribunals have characterized traditional fishing rights as ‘vested rights’ falling within the renvoi ‘other rules of international law’ under Article 2(3) of the LOSC (see for example, the South China Sea Arbitration, [808]).

The South China Sea Tribunal further concluded that the ‘attention paid to traditional fishing rights in international law stems from the recognition that traditional livelihoods and cultural patterns are fragilein the face of development and modern ideas of interstate relations and warrant particular protection’.

Such conclusion conforms with existing state practice and scholarly writings.

As for the continuity of traditional fishing rights within the EEZ, the jurisprudence on the matter is inconsistent, scholars remain divided, and the existing state practice is limited.

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the LOSC does not preclude states from recognizing and protecting traditional fishing rights within the EEZ by mutual agreement.

Thus, this indicates that coastal states have an obligation to take measures to continue recognizing the traditional rights of indigenous peoples while delimiting their maritime boundaries.

In this respect, the recognition of the traditional rights of the Inuit peoples over Tartupaluk resonates with the obligation of states under international law.

Regulating cross-border traditional activities on the entirety of Tartupaluk seems to be aligned with the relevant provisions of the instruments discussed above.

Nonetheless, the Agreement suffers from certain limitations.

The free movement regime established by the Agreement is applicable only to a tiny uninhabited territory of 1. 3 km², as the Agreement does not expressly extend such rights to the water/sea-ice surrounding the island.

Moreover, while Canada and Denmark consulted their respective Inuit people under their domestic law, the Inuit peoples from both sides did not directly take part in the negotiations leading to the 2022 Agreement.

This approach also raises questions as to its consistency with Canada’s commitment under para. 5.9.2 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, which requires the Government of Canada to include Inuit representatives when negotiating an international agreement relevant to Inuit wildlife harvesting rights in the Nunavut Settlement Area.

Nor does the 2022 Agreement establishes an institutional framework that monitors the implementation of Inuit rights recognized by the Agreement, and that allows for the continued participation and consultation of the Inuit peoples on matters that may affect their rights.

For example, such mechanisms include liaison offices, or a common forum for the Inuit peoples from both sides, or a joint commission that includes representatives of the Inuit peoples.

These types of creative participatory and consultative approaches exist in state practices in the Indo-Pacific region, such as the Torres Strait Treaty.

As for the continuity of traditional fishing rights within the EEZ, the jurisprudence on the matter is inconsistent, scholars remain divided, and the existing state practice is limited.

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the LOSC does not preclude states from recognizing and protecting traditional fishing rights within the EEZ by mutual agreement.

Thus, this indicates that coastal states have an obligation to take measures to continue recognizing the traditional rights of indigenous peoples while delimiting their maritime boundaries.

In this respect, the recognition of the traditional rights of the Inuit peoples over Tartupaluk resonates with the obligation of states under international law.

Regulating cross-border traditional activities on the entirety of Tartupaluk seems to be aligned with the relevant provisions of the instruments discussed above.

Nonetheless, the Agreement suffers from certain limitations.

The free movement regime established by the Agreement is applicable only to a tiny uninhabited territory of 1. 3 km², as the Agreement does not expressly extend such rights to the water/sea-ice surrounding the island.

Moreover, while Canada and Denmark consulted their respective Inuit people under their domestic law, the Inuit peoples from both sides did not directly take part in the negotiations leading to the 2022 Agreement.

This approach also raises questions as to its consistency with Canada’s commitment under para. 5.9.2 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, which requires the Government of Canada to include Inuit representatives when negotiating an international agreement relevant to Inuit wildlife harvesting rights in the Nunavut Settlement Area.

Nor does the 2022 Agreement establishes an institutional framework that monitors the implementation of Inuit rights recognized by the Agreement, and that allows for the continued participation and consultation of the Inuit peoples on matters that may affect their rights.

For example, such mechanisms include liaison offices, or a common forum for the Inuit peoples from both sides, or a joint commission that includes representatives of the Inuit peoples.

These types of creative participatory and consultative approaches exist in state practices in the Indo-Pacific region, such as the Torres Strait Treaty.

Conclusion

The resolution of the last sovereignty-related territorial dispute over the Arctic circle meant a historic deal for the sovereign states of Canada and the Kingdom of Denmark, and not least for the Inuit on both sides who saw the integrity of the traditional territories being to some extent recognized.

Yet, the acknowledgement of the integrity of Inuit territories is limited to a small uninhabited island and does not extend to marine areas.

The agreement may thus have a more symbolic rather than pragmatic value for traditional activities, even more for the Inuit of Canada.

What is most important though is that maintaining the traditional, symbolic, and historic significance of Tartupaluk both to the Inughuit of Avanersuaq and to the Inuit of Nunavut constitutes the very first step towards the acknowledgment of the entirety of the traditional territories of an Indigenous people currently spread among four Arctic sovereign states.

With the Arctic warming several times faster than the rest of the world, and both human and animal traffic gradually moving northwards, the Tartupaluk island itself could potentially become a more attractive site for subsistence hunting activities in the North and the 2022 Agreement a point of departure for future transboundary legal developments.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Canada's territorial disputes

- NYTimes : Canada and Denmark Fight Over Island With Whisky and Schnapps

- WP : Ukraine war brings peace — between Canada and Denmark

- ArticToday : Canada, Denmark agree on a landmark deal over disputed Hans Island

- BusinessInsider : The Whisky War: Why history's most polite territorial conflict rages on

- LOC : The Hans Island “Peace” Agreement between Canada, Denmark, and Greenland

- Big Thinjk : On tiny Hans Island, Denmark and Canada create world’s newest land border

Sunday, January 29, 2023

Tempete sur Le Four

On the morning of 22 November 2022, the wind was still blowing at over 40 knots in the Le Four channel.

source : Nautimages

17 January 2018. After the passage of the storm Fionn, the sea remains very rough and huge waves break on the Four lighthouse in the Iroise Sea.

The lighthouse's lantern is 31 metres high (plus 4 metres because it is low tide), the height of a 12-storey building...

Wind gusts of over 100 km/h cause the tripod to vibrate in ways that are impossible to control.

Wind gusts of over 100 km/h cause the tripod to vibrate in ways that are impossible to control.

source : Christian Kerglonou

Localization with the GeoGarage platform (SHOM raster chart)

Saturday, January 28, 2023

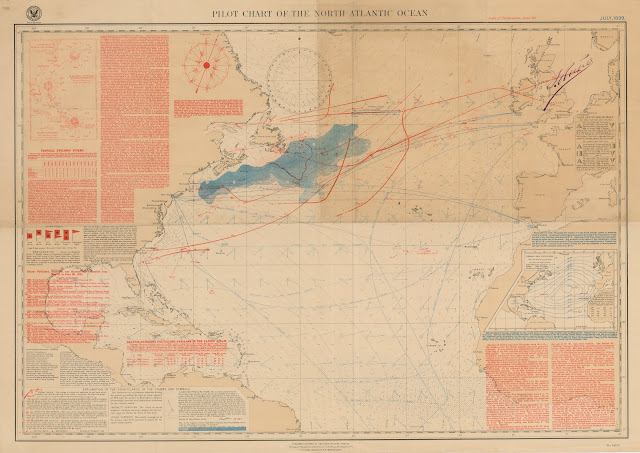

Pilot chart of the North Atlantic Ocean (1899)

source : NGA

Pilot Charts depict averages in prevailing winds and currents, air and sea temperatures, wave heights, ice limits, visibility, barometric pressure, and weather conditions at different times of the year.

The information used to compile these averages was obtained from oceanographic and meteorologic observations over many decades during the late 18th and 19th centuries.

The Atlas of Pilot Charts set is comprised of five volumes, each covering a specific geographic region.

The Atlas of Pilot Charts set is comprised of five volumes, each covering a specific geographic region.

Each volume is an atlas of twelve pilot charts, each depicting the observed conditions for a particular month of any given year.

The charts are intended to aid the navigator in selecting the fastest and safest routes with regards to the expected weather and ocean conditions.

The charts are intended to aid the navigator in selecting the fastest and safest routes with regards to the expected weather and ocean conditions.

The charts are not intended to be used for navigation.

Friday, January 27, 2023

Sailor Isabelle Autissier: ‘The ocean is the axis around which my life has turned’

The legendary yachtswoman on sailing the globe single-handed, near-death experiences in the Southern Ocean — and why our approach to the environment is all wrong

More than half a century ago on a winter’s day in the English Channel, a 10-year-old French girl stood half-frozen on the deck of a sailing boat, mesmerised by the sight of snow falling into the sea and dissolving in the waves off the coast of Jersey.

She had vowed that one day she would sail around the world alone and was braving the cold and the snow to prepare for the icy Southern Ocean.

That girl was Isabelle Autissier and she has more than fulfilled her wish, she tells me shortly after we have collided at the entrance to Les 4 Sergents, the restaurant she has chosen for our lunch, near her home in the Atlantic port of La Rochelle.

Her shock of curly hair and wry smile are instantly recognisable to those who follow sailing.

She has been around the world four times under sail, and in the course of becoming one of the best-known sportswomen in France — the nation most fanatical about single-handed sailing — she broke records, became the first woman to circumnavigate solo in a race and was twice rescued from the mountainous seas that encircle the South Pole.

Today she is a prominent novelist, broadcaster and environmentalist seeking to preserve the seas that enchanted her as a child.

And she still sails regularly in the remote polar regions.

“The ocean is the axis around which my life has turned since the beginning, since I’ve begun thinking about it, from a very young age.

Sailing is at the heart of it,” she says as we take our places under the restaurant’s elegant glass and metal canopy, manufactured at Gustave Eiffel’s workshop.

It covers what used to be a garden and is now the dining room.

(The four sergeants were Bonapartists guillotined in 1822, and legend has it that two of them briefly escaped from prison in the nearby Tour de la Lanterne and hid here.) The charts are wrong, so you end up in places where you have no idea where you’re going . . . It’s pretty exciting in terms of navigation — and it’s magnificent I am eager to ask Autissier not just about her sailing feats but also about her life as a writer — she has even done an opera libretto — and as a leader of the World Wide Fund for Nature who says our planet should be called the Sea, not the Earth.

But, as a timid sailor myself, I have to know about her experiences in the Southern Ocean: once she waited four days with her wrecked boat before being rescued by an Australian navy helicopter, and in another race she was lucky to be found and plucked to safety from her overturned yacht by fellow sailor Giovanni Soldini.

Back in 1997, Canadian skipper Gerry Roufs died in the Vendée Globe race when violent winds and waves overturned his boat and Autissier was unable to find him.

Autissier is phlegmatic about her shipwrecks and matter-of-fact about the possibility of dying.

“It’s true that I’ve twice found myself in these situations but these things can happen.

On the first occasion, I was dismasted, stopped at Kerguelen, built a jury-rig mast and set off again before being completely turned over by a huge wave.

“The boat was really destroyed, it ripped off the cabin top.

But on both occasions I felt more or less the same thing.

I didn’t panic — I am not saying that to . . .

it’s just that I was immediately pragmatic.

The first time my boat rolled over and came back I saw it was full of water.

I took a bucket and emptied it.

And then I started to think, what should I do? That was when I set off the distress beacon.

“I think I’m pretty optimistic.

The idea is to fix things.

If there is a problem to solve, you solve it.

And if you don’t, well, life ends some day.

Better later than sooner, but there you are . . . When you are sailing, you always think about what could happen in two hours, in six hours, in 24 hours.

And you think about Plan A, Plan B and Plan C.

What do I do if this doesn’t work, or if that breaks?

You have a kind of mental machinery that prepares you.”

That makes you a good skipper, I say, as we embark on our entrées — butternut velouté for Autissier and a delicate crabmeat starter with a hint of wasabi for me.

We are engrossed in our conversation, and she is as matter-of-fact about food as she is about sailing and death.

When I urge her to comment on her dish in keeping with the traditions of Lunch with the FT, she briskly describes the soup in one word as “delicious” but remarks that she once had a “blind meal” that proved how hard it is to tell the difference between carrots and potatoes when you cannot see what you are eating.

She has stronger opinions about the wine, immediately choosing a glass of Bourgueil red for herself and commenting on my choice of a white from the local Vendée region: “They’ve got a hell of a lot better — 15 years ago they were awful.”

We are engrossed in our conversation, and she is as matter-of-fact about food as she is about sailing and death.

When I urge her to comment on her dish in keeping with the traditions of Lunch with the FT, she briskly describes the soup in one word as “delicious” but remarks that she once had a “blind meal” that proved how hard it is to tell the difference between carrots and potatoes when you cannot see what you are eating.

She has stronger opinions about the wine, immediately choosing a glass of Bourgueil red for herself and commenting on my choice of a white from the local Vendée region: “They’ve got a hell of a lot better — 15 years ago they were awful.”

This lunch on a rainy winter’s day in La Rochelle has been many months in the making because Autissier always seems to be away sailing.

She has just returned from the Leeward Islands in French Polynesia but suggests it was too easy and comfortable to be the kind of “challenging” (she uses the English word) expedition she favours.

So where is she going next?

Now 66, she has given up single-handed racing and prefers exploring “in absolute freedom” in the company of scientists (she initially studied crustaceans and first came to La Rochelle as a fisheries researcher), as well as artists and mountaineers who need a ride to difficult places without airports or roads.

“I do what I want, with whom I want, where I want,” she says.

Her own boat these days is not a lightweight racing machine but a robust aluminium yacht that does not depend on corporate sponsors and that she describes as an off-road “mountain bike of the sea”.

The boat is in Iceland and her next trip is to Greenland.

“I do what I want, with whom I want, where I want,” she says.

Her own boat these days is not a lightweight racing machine but a robust aluminium yacht that does not depend on corporate sponsors and that she describes as an off-road “mountain bike of the sea”.

The boat is in Iceland and her next trip is to Greenland.

Why are we in this absolute denial about where we are and where we’re going?

Autissier grew up in the Paris region and was introduced to sailing by her parents, who owned dinghies and then a keelboat that her father shared with 16 partners to reduce the cost and keep the boat sailing through the year — not just for the typical two weeks in the summer.

“They were écolos [greens] before their time,” she says with a grin.

“When I was little, I got tired of dolls pretty quickly.

Tool boxes, on the other hand, I adored.” In her early twenties, she made her own yacht in the old warehouse area of La Rochelle after buying a steel hull “like a rusty bathtub”.

She quit her job, set off to Africa and Brazil with friends and insisted on returning single-handed across the Atlantic from the Caribbean.

She was hooked.

“They were écolos [greens] before their time,” she says with a grin.

“When I was little, I got tired of dolls pretty quickly.

Tool boxes, on the other hand, I adored.” In her early twenties, she made her own yacht in the old warehouse area of La Rochelle after buying a steel hull “like a rusty bathtub”.

She quit her job, set off to Africa and Brazil with friends and insisted on returning single-handed across the Atlantic from the Caribbean.

She was hooked.

That all makes sense to an amateur who sails for pleasure, but why the urge to go to the extreme and frigid latitudes near the poles?

First, she explains patiently to someone who has never seen an iceberg, it is the breathtaking landfalls, and the angle and unpolluted clarity of the polar light.

Then there’s the ice and unspoilt beauty of the landscape, and the lack of fear among the wild animals that elsewhere flee at the sight of humans.

Then there’s the ice and unspoilt beauty of the landscape, and the lack of fear among the wild animals that elsewhere flee at the sight of humans.

Finally, for a woman whose achievements include smashing the speed record for the 19th-century gold rush sailing route from New York around Cape Horn to San Francisco, there is that matter of the challenge:

“It’s more fun.The charts are wrong, so you end up in places where you have no idea where you’re going . . . It’s pretty exciting in terms of navigation — and it’s magnificent.” I am thinking that it also sounds cold and frightening, but having read several of her books in recent weeks to prepare for our lunch, I turn to her second career as a successful novelist and suggest that her strong, solitary female characters are in her own image: the young eco-activist Léa, for example, in Le Naufrage de Venise (“The Sinking of Venice”, a futuristic tale published last year about a climate-related disaster), or Louise, one half of the sailing couple stranded on an abandoned whaling island in Soudain, Seuls (“Suddenly Alone”), her most successful novel so far.

It makes me sad to say that we have to suffer in order to stop being idiots

“People have told me I write feminist novels.

Well, that’s great but I didn’t ...”

Well, that’s great but I didn’t ...”

She pauses and I suggest she did not do it deliberately.

“No,” she agrees.

“What I did do somewhat deliberately in Soudain, Seuls, for example, was to try not to fall into the cliché where it’s the man who braves the elements and solves the problems and everything.

“From a novelistic point of view it was more interesting that it should be this apparently physically frail young woman . . . And also, why not? When you look at women in the world, many of them have extraordinary courage and tenacity, and it’s often those with the least resources who end up alone with a child and no money.

It’s not genetic in my opinion, it’s cultural.

Women tend to end up in more difficult and demanding situations than men.” She has no children herself, but enjoys her six nieces and nephews and was partner for a time of a man who had two children.

“No,” she agrees.

“What I did do somewhat deliberately in Soudain, Seuls, for example, was to try not to fall into the cliché where it’s the man who braves the elements and solves the problems and everything.

“From a novelistic point of view it was more interesting that it should be this apparently physically frail young woman . . . And also, why not? When you look at women in the world, many of them have extraordinary courage and tenacity, and it’s often those with the least resources who end up alone with a child and no money.

It’s not genetic in my opinion, it’s cultural.

Women tend to end up in more difficult and demanding situations than men.” She has no children herself, but enjoys her six nieces and nephews and was partner for a time of a man who had two children.

She has no regrets now that she spent her childbearing years sailing around the world.

“I have friends who were very attracted by motherhood, who want that experience of being pregnant, but it didn’t really grab me.” As for Soudain, Seuls, a modern Robinson Crusoe story with a woman protagonist, it has been or is being translated into 10 languages and will come out soon as a film.

And she likes to try new things.

The other day, I saw her on stage at a small Paris theatre telling tales of the sea.

And she wrote a “slightly wacky” climate-themed opera called Homo Loquax with her musical partner Pascal Ducourtioux, performed by Radio France and in provincial theatres, in which the words used by people over the centuries are released from the melting ice caps and fly back to be heard in the places where they were first spoken.

Ours turns out to be a typically French two-hour lunch, but we are making quick work of our main courses — a vegetarian platter with risotto for her and a rather chewy baked monkfish for me (I should have remembered that is the nature of the lotte) — and I want to ask about her life as an environmentalist before we get to the coffee.

For obvious reasons, sailors often turn to green causes — think of the UK’s Ellen MacArthur and her campaigns against plastic waste — and I worried when I started reading Le Naufrage de Venise that it would be a kind of angry environmentalist tract thinly disguised as fiction.

Instead, while the climate message is unmistakable, I found it well plotted and the characters engaging.

After surviving the Venice disaster, the feisty and solitary Léa remains estranged from her mercenary politician father and faces an uncertain future on the mainland.

“She’ll become a climate activist and perhaps you’ll see her chucking pots of mayonnaise at famous paintings,” Autissier says with a laugh.

Like me, Autissier is baffled that global warming — for which she sees the evidence in the melting ice of the Arctic and the Antarctic — has become a divisive political issue, a phenomenon that climate-change deniers see as a matter of faith rather than simply a reality we need to address.

Why, she wonders, did it take the Ukraine war to persuade Europeans to save energy and invest more in renewable energy? “It makes me sad to say that we have to suffer in order to stop being idiots.

I would prefer that we be idiotic for as short a time as possible.

The idea of sustainable development as a kind of equal interaction between economics, society and the environment is all wrong “On Venice [and sea-level rise], one of the questions I asked myself was about denial.

Why are we in this absolute denial about where we are and where we’re going? It’s not as if we don’t have the facts.

The IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] has been telling us everything for 40 years . . . It’s incredibly clear.”

She adds that the idea of sustainable development as a kind of equal interaction between economics, society and the environment is all wrong, because the reality is more like a multi-tiered wedding cake with the planet and its physical functioning at the base and everything else on top.

If you destroy the environment, the rest, including human society, collapses.

Talk of Ukraine leads to a discussion of cold childhood homes and how much more economical our prewar parents’ generation were than their children and grandchildren — and to dessert.

If you destroy the environment, the rest, including human society, collapses.

Talk of Ukraine leads to a discussion of cold childhood homes and how much more economical our prewar parents’ generation were than their children and grandchildren — and to dessert.

She picks the lime pudding, while the three homemade sorbets I choose — fig, red fruits and pear — were by a long way my best course and come close to the perfection of Vivoli’s gelato in Florence.

Over coffee I realise that instead of arguing, we seem to agree on just about everything — the joy of night sailing and looking at the stars, a preference for paper over electronic nautical charts, the folly of Brexit, the failure of France’s Emmanuel Macron to go down in history as an environmental president even though he makes a lot of speeches — so I bring her back to the question of the oceans and the planet and what any of us can actually do to save them.

“There is a lack of scientific culture, and a lack of contact with nature.

When you are in the natural world you can say what you like but nature has the last word: if it’s cold, it’s cold, and if it’s hot it’s hot, whether it suits you or not.

So people take refuge a lot in the virtual world, live virtual lives.

All that means a lack of understanding, a lack of rigour, and we get emotion and all kinds of nonsense instead, to the extent that people think the opinion of a physics professor with 30 years of research is no more valid than that of my neighbour who walks outside and says it’s cold today so there can’t be any global warming.” As a scientist by training, she chose WWF, where she was president in France and is now honorary president, as the vehicle for her environmental work because of its focus on science.

“I try to be active. Being optimistic or pessimistic doesn’t help anyone — that’s my pragmatic side — so I do things instead.

And that is important to me because it helps escape the distress.

It’s terrible to see the world collapsing around us or, when I’ve got nephews and nieces — I’m even a great-aunt now — to think about this bad news all the time.”

How long can she go on sailing and campaigning?

“I’m 66, so it’s still fine, although of course like everyone there will come a day when I can’t any more.

I reckon I’ve got at least 10 more years, and after that, we’ll see.”

I reckon I’ve got at least 10 more years, and after that, we’ll see.”

With that, we say our farewells and she rides off on her bicycle to prepare for the next adventure.

Thursday, January 26, 2023

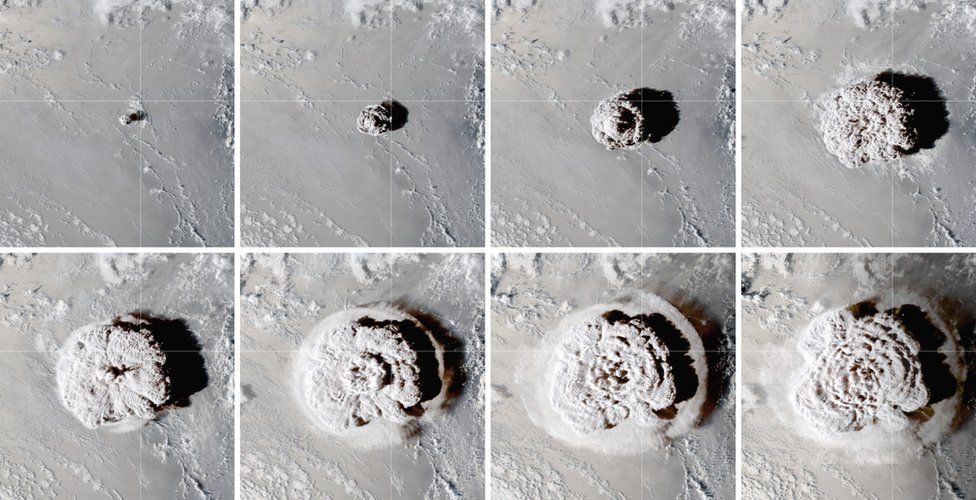

The Tonga eruption is still revealing new volcanic dangers

NASA / Science photo Library

One year later, researchers are still marveling at the power of the Hunga Tonga explosion—and wondering how to monitor hundreds of other undersea volcanoes.

Last year, Larry Paxton was looking at the edge of space when he saw something he shouldn’t.

A physicist at Johns Hopkins University, Paxton uses satellite-based instruments that look down on the region of space just above the atmosphere.

They see in spectrums of light that we can’t, like the far ultraviolet, monitoring for things like odd space weather.

But in late January, his team observed something unusual on a scan: Part of the map had gone dark.

The rays of far UV light were being absorbed by molecules of some sort, resulting in a dim splotch roughly the size of Montana.

The source soon became clear: the Hunga Tonga volcano, which had just erupted in the South Pacific.

Those molecules—enough water, Paxton’s team later determined, to fill 100 Olympic swimming pools—had been jettisoned skyward faster than the speed of sound by an explosion unlike anything previously recorded on Earth.

“This is an enormous amount of water to get injected that high,” says Paxton, who presented his research a few weeks ago at the American Geophysical Union.

“It’s an extraordinary thing.”

One year later, scientists studying virtually every facet of the Earth, from the mantle to the oceans to the ionosphere, have had a moment similar to Paxton’s, stunned by some superlative discovery generated by the Hunga eruption.

In recent months, scientists have observed new vibrational waves that ricocheted around the globe, triggering tsunamis in distant ocean basins, and seen the highest concentration of lightning ever recorded.

The newly cosmic water molecules represented the very top of an enormous plume that filled the upper atmosphere with enough water to trap heat underneath, likely warming the Earth slightly for the next few years, according to Holger Vömel, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The January 15, 2022 explosion was obviously strange.

But now researchers are asking: Just how singular was it? The answer has implications for the hundreds of underwater volcanoes dotting the Earth’s oceans.

“The Hunga eruption highlights a new type of volcano, and new types of underwater threats,” says Shane Cronin, a volcanologist at the University of Auckland.

And yet only a handful of underwater volcanoes have been the site of extensive research.

Those include the Axial seamount, which lies a few hundred miles off the coast of Oregon and has been studied since the 1970s, and the long-active Kick ’em Jenny near the Caribbean nation of Grenada.

Both receive regular visits from research cruises and are covered with sensors that monitor for rumbles.

But many more are found in remote arcs of the Pacific, far from big cities or ports where research vessels make harbor.

Their closest neighbors are small island nations, like Tonga, that don’t have dedicated volcano-monitoring programs or much capacity to install seismic monitors.

That’s in part due to geographical problems.

Tonga, for example, is a line of islands, which isn’t great for triangulating the sources of seismic waves—and staffing and funds can be scarce in countries where the population is similar in size to a large US town.

There are international options, like the US Geological Survey’s Seismic Monitoring Network, that offer global coverage for unusual geologic activity, but the stations are generally too few and far between to pick up the softer rumbles foretelling a coming undersea eruption, says Jake Lowenstern, director of the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program at USGS.

Most of those eruptions have no chance of matching the explosiveness of Hunga Tonga.

But the event awakened the world to the possibile activity of these volcanoes, says Sharon Walker, an oceanographer at the Pacific Marine Environment Laboratory.

“While events like this don’t happen very often, my feeling is that we do not want them to happen on our watch,” she says.

It’s clear that Hunga involved an unusually explosive recipe that may not be easily replicated.

For about a month, the eruption had progressed as expected—moderately violent, with gas and ash, but manageable.

Then everything went sideways.

That appears to be the result of at least two factors, Cronin says.

One was the mixing of sources of magma with slightly different chemical compositions down below.

As these interacted, they produced gasses, expanding the volume of the magma within the confines of the rock.

Under tremendous pressure, the rocks above began to crack, allowing the cold seawater to seep in.

“The seawater added the extra spice, if you like,” Cronin says.

A massive explosion ensued—two of them actually—which blew trillions of tons of material straight out through the top of the caldera, some of it apparently all the way to space.

Both of those explosions produced big tsunamis.

But the biggest wave came later—potentially caused, Cronin thinks, by water flooding into the kilometer-deep hole suddenly dug out of the seafloor.

“That’s something really new for us,” he says—a new type of threat to consider elsewhere.

Previously, scientists thought that this kind of volcano could only really produce a big tsunami if a side of a caldera collapsed.

The bottom line, he says, is that submarine volcanoes are more diverse, and in some cases more capable of extreme behavior, than anyone thought.

But the process of piecing the eruption together has also highlighted the challenges of studying submarine volcanoes.

A typical mapping expedition will involve a large, fully crewed research vessel, equipped with multibeam sonar that maps the seafloor for changes and a battery of water sampling instruments that search for chemical signs of ongoing activity.

But taking a boat over a potentially active caldera is risky—not so much because the volcano might blow, but because the gas bubbles burbling up might cause a ship to sink.

In Tonga, researchers solved that problem with smaller ships and an autonomous vessel.

Even Tonga, which has been visited four times in the past year due to an influx of research funding to groups studying the eruption, isn’t likely to get another big crewed mission in the next few years, Cronin says.

The cost is just so high.

It would likely take decades to survey every volcano in detail, even just those in the Tongan arc.

This is a shame, Walker says, because those kinds of expeditions are one of the few ways scientists get close enough to actually see how volcanoes are behaving.

An ideal scenario would involve more funding for those missions, as well as investment in improving new technology, like the autonomous vessels, which can be tricky to operate in the treacherous open ocean.

Without them, scientists are stuck watching from a distance.

This is hard to do when you’re trying to observe underwater events—but not impossible.

Satellite technology can spot objects known as pumice rafts—sheets of buoyant volcanic rock that bob on the water’s surface—as well as algal blooms, which are nurtured by the minerals released by volcanoes.

And the USGS, as well as counterparts in Australia, are in the process of installing a network of sensors around Tonga that can better detect volcanic activity, combining seismic stations with sound sensors and webcams that watch for active explosions.

Ensuring it stays up and running will be a challenge, Lowenstern says—a matter of keeping the systems connected to data and to power sources and ensuring Tonga can staff the facilities.

He adds that Tonga is just one of many Pacific nations that could use the help.

But it’s a start.

One of the benefits of studying the Hunga volcano so closely is that researchers have now identified new volcanic features to watch out for.

Over the next few years, Cronin foresees a process of identifying which volcanoes require more attention.

On their final Hunga voyage of 2022, Cronin’s team made use of the time on the ship to visit two other submarine volcanoes in the area, including one about 100 miles north with a mesa-like topography that resembles Hunga before its eruption.

The maps will be a baseline for future surveys that manage to get out on the water, a way for researchers to figure out how much action is happening underneath sea and rock.

So far, Cronin reports, the ocean is quiet.

Links :

- NASA : Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai Erupts

- BBC : Tonga volcano eruption continues to astonish

- Reuters : One year after volcanic blast, many of Tonga's reefs lie silent

- Forbes : Tonga Marks The First Anniversary Of The Devastating Hunga Eruption And Tsunami

- Chemistry World : One year on from massive eruption in South Pacific, the atmosphere is still feeling the effects

- Space : Hunga Tonga undersea volcano eruption likely to make ozone hole larger in coming years

- CNRS : Learning the lessons of the Hunga Tonga eruption

- GeoGarage blog : Tonga eruption confirmed as largest ever recorded

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

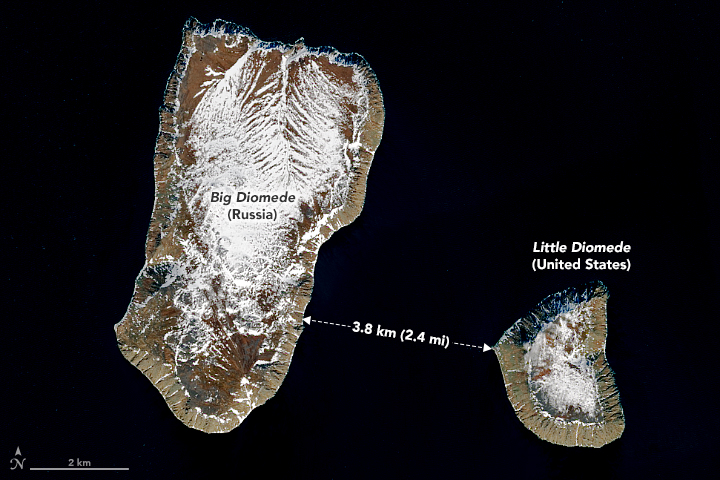

Yesterday and Tomorrow islands (Dioméde islands)

June 2, 2017

June 1, 2017

From NASA by Kathryn Hansen

Today’s caption is the answer to our January 2018 puzzler.

Here’s a bit of trivia to challenge your geography knowledge:

Which country is closest to the continental United States without sharing a land border?

The answer is revealed in the top image, which shows the eastern part of Russia and western part of the United States.

The answer is revealed in the top image, which shows the eastern part of Russia and western part of the United States.

This image was acquired on June 2, 2017, by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NASA-NOAA Suomi NPP satellite.

At the narrowest part of the Bering Strait, about 82 kilometers (51 miles) is all that separates Cape Dezhnev on the Chukotka Peninsula and Cape Prince of Wales on mainland Alaska.

But Russia’s Big Diomede Island is even closer to mainland Alaska, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) away, making it the closest non-border-sharing country to the continental U.S.

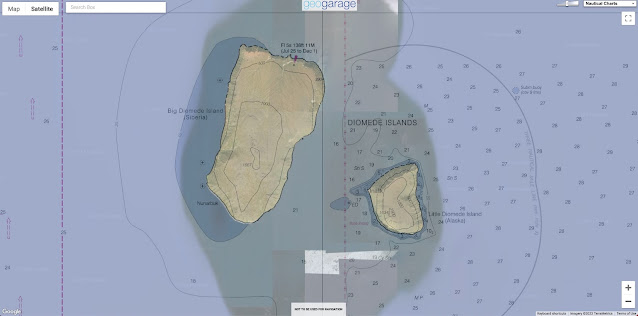

Diomede islands with NOAA nautical raster charts in the GeoGarage platform

The distance between the two countries is actually much smaller.

Just 3.8 kilometers (2.4 miles) separate Big Diomede Island (Russia) and Little Diomede Island (U.S.).

The island pair is visible in the detailed image, acquired on June 6, 2017, by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8.

Summer temperatures on the islands average about 40 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

Wintertime is even colder, averaging between 6 and 10°F.

Each year, Arctic sea ice extends southward into the strait from the Bering and Chukchi seas.

By June, however, melting usually causes the ice edge to retreat northward, leaving open water that appears black in these images.

The water between the two islands is bisected by the maritime border of the two countries.

The water between the two islands is bisected by the maritime border of the two countries.

The passage was historically nicknamed the “ice curtain,” which had more to do with Cold War tensions than climate.

Today, Little Diomede has a small permanent community—about 115 people according to the 2010 U.S. census.

The town is located on a small beach on the island’s western side, meaning that Russia’s Big Diomede and even the mainland are visible from the homes.

RU4OH1S0 ENC Bering Sea- Bering Strait - Diomede Islands - Approaches to Ratmanov Island (1:22,000)

Another invisible line runs between the islands and inspired the nicknames “Yesterday” and “Tomorrow” islands.

Big Diomede and Little Diomede sit on opposite sides of the International Date Line.

International border and date line

Big Diomede is almost a day ahead of Little Diomede, but not completely; due to locally defined time zones, Big Diomede is only 21 hours ahead of Little Diomede (20 in summer).

Diomede Islands: Little Diomede Island or Kruzenstern Island (left)

and Big Diomede Island or Ratmanov Island in the Bering Sea. Photo is

from the north.

photo : Dave Cohoe

photo : Dave Cohoe

As Earth Observatory reader Jim Andersen commented on our blog: “When you look at the Big Diomede Island, you’re looking into the future!”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and VIIRS data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and VIIRS data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership.

Links :

- Douglas, D.C. (2010) Arctic sea ice decline: Projected changes in timing and extent of sea ice in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report, 2010-1176, 32 p.

- Kawerak, Inc. (2013) Diomede Local Economic Development Plan 2012-2017. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- The New York Times (1988, October 23) Lifting the Ice Curtain. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- BBC : The ice curtain that divides US families from Russian cousins

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

After 20 years of service, AIS is about to get a big upgrade

From Maritime Executive

The Automated Identification System (AIS) has served the maritime industry for more than 20 years, and it has revolutionized the way that mariners, regulators and industry stakeholders do business.

AIS makes it easy for watchstanders to identify a target and make passing arrangements, and it gives Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) operators the transparency they need to ensure safety on busy waterways.

Thanks to satellite- and shore-based AIS reception, commodity traders and researchers can study marine traffic patterns for insight into the movements of global commerce.

AIS makes it easy for watchstanders to identify a target and make passing arrangements, and it gives Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) operators the transparency they need to ensure safety on busy waterways.

Thanks to satellite- and shore-based AIS reception, commodity traders and researchers can study marine traffic patterns for insight into the movements of global commerce.

However, the industry has gotten bigger and busier over the past two decades, and it's time for an update.

In some coastal areas - the Singapore Strait, China's megaports, parts of Japan - there are so many vessels that the performance of AIS has been affected.

As traffic density goes up, the system's range goes down, and the frequency of updates becomes more random.

This has the biggest impact on shoreside observers like VTS operators, according to engineers for leading VDES system developer Saab TransponderTech.

The fix is to update classic AIS with a new digital system, something more robust and capable of handling more bandwidth.

After years of consultation, maritime technology experts and regulators have come up with a solution: VDES (VHF Data Exchange System), a new system which will give operators higher security and reliability.

VDES will operate on additional new frequencies and will use them more efficiently, enabling 32 times as much bandwidth for secure communications and e-navigation.

It will be able to handle higher traffic density and more frequent vessel movement updates, and it is designed to meet the needs of maritime users for the next 20 years.

It also has new features which AIS lacks.

When two ships get close to each other, they will automatically exchange data on their future routes, not just their current positions.

This will increase situational awareness and reduce ambiguity in traffic situations.

Shoreside authorities can use the same data-transfer capabilities to broadcast digital updates, like safety-related text messages and boundary lines for cautionary areas.

VDES is also purpose-built for communication with low earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations, ensuring genuine over-the-horizon connectivity from the start.

Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) operators will be among the biggest beneficiaries, as satellite functionality will extend the range of reception and enable supervision over a larger area.

Cybersecurity is also enhanced thanks to VDES' ability to send encrypted positions, reducing the chance of spoofing.

Onboard position tampering to disguise the ship's movements - a common technique used by vessel operators for sanctions violations, illegal fishing and smuggling - can be detected and thwarted.

In some coastal areas - the Singapore Strait, China's megaports, parts of Japan - there are so many vessels that the performance of AIS has been affected.

As traffic density goes up, the system's range goes down, and the frequency of updates becomes more random.

This has the biggest impact on shoreside observers like VTS operators, according to engineers for leading VDES system developer Saab TransponderTech.

The fix is to update classic AIS with a new digital system, something more robust and capable of handling more bandwidth.