People looking at the Huang-Ming Yitong Da Tu (Unified Atlas of the August Ming) at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, part of an exhibition called “The World on Paper: From Square to Sphericity”. Photo: Antony Dickson

From South China Morning Post by Stuart Heaver- A show of 80 historic maps and charts reveal China’s view of itself over the centuries and give clues on why the country now conducts business as it does

- The exhibition at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum also shows that the West’s view of China was long distorted

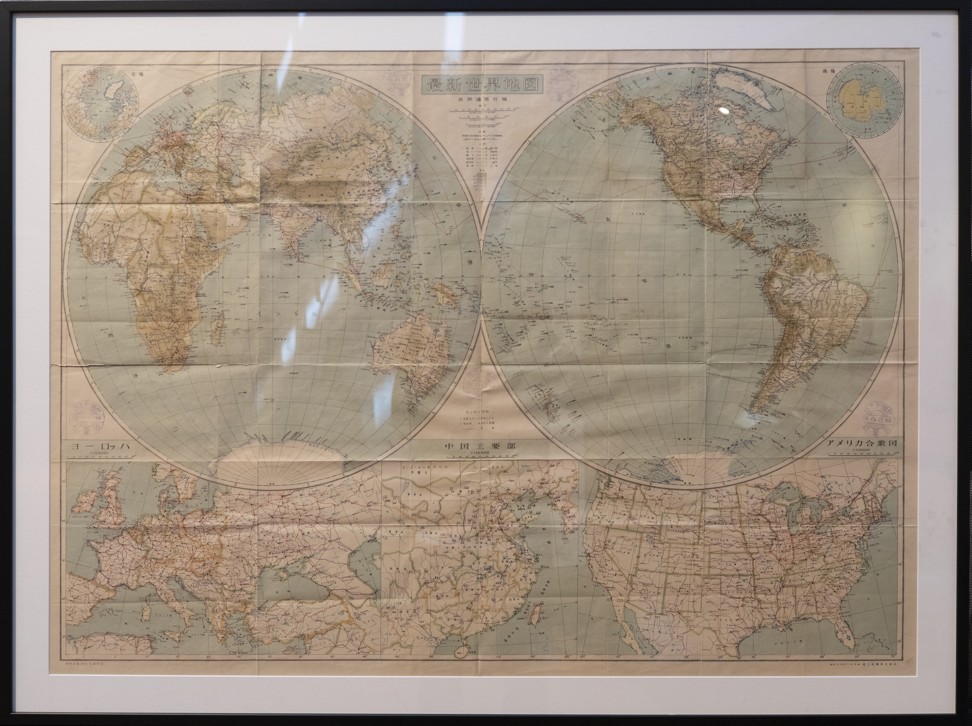

The map, whose title translates as the Unified Atlas of the August Ming, is one of 80 historic maps and nautical charts on display at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum as part of an exhibition called “The World on Paper: From Square to Sphericity”.

“Maps both reflect history and are a record of history,” says collector Tam Kwong-lim, who helped curate the exhibition.

Running until February 24, the exhibition not only follows the evolution of Chinese navigation and cartography, but reveals how China saw itself in the world and how the rest of the world perceived China.

Tam Kwong-lim at the exhibition at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum.

Photo: James Wendlinger

Tam bought his first old map of China in a second-hand bookshop in Tokyo while working in the city as a shipping executive in the 1970s.

He has since been an avid collector and is now recognised as an authority on antique maps and charts, which, he points out, still influence modern geopolitical and territorial disputes.

He points to a 1951 Japanese chart showing the South China Sea that is clearly marked in red ink as “China”.

Another Japanese chart, produced in 1943 and including the Philippines, shows a thick boundary line drawn around the

hotly disputed Spratly Islands, excluding them from control of the Philippines, which was occupied by the Japanese at the time.

Museum director Richard Wesley says the old maps help shed light on how the modern Chinese state goes about its business.

“China is now recognised as a global economic superpower, but to better understand the Chinese approach to international trade and diplomacy, it can be helpful to examine how they saw the world and how they mapped it,” he says.

A Japanese map produced in 1951 at the exhibition which shows the South China Sea as clearly belonging to China.

Photo: Antony Dickson

Although China had been producing maps since the Han dynasty (206BC-AD220), there was no attempt to accurately chart its national boundaries or undertake scientific surveys of its territory, Tam says.

It didn’t need to.

Traditional Chinese thinking was greatly influenced by the concept of a “canopy heaven” represented by a spherical heaven and flat Earth.

Everything inside China was ruled over by the emperor.

Everything outside that empire was the world of barbarians and hardly worth bothering about.

Even as trade routes to the Arabian Peninsula developed in the Song dynasty (960-1279), this self-centric view of China at the centre of the heavenly universe remained firmly in place.

Early maps of China had more of a municipal function, showing settlements, roads and geographical features, often with great artistic flourish.

“The maps were drawn like Chinese paintings, depicting rivers and mountains – what was important was the distribution of cities and centres of population density, because they had more of an administrative purpose than a navigational purpose,” Tam says.

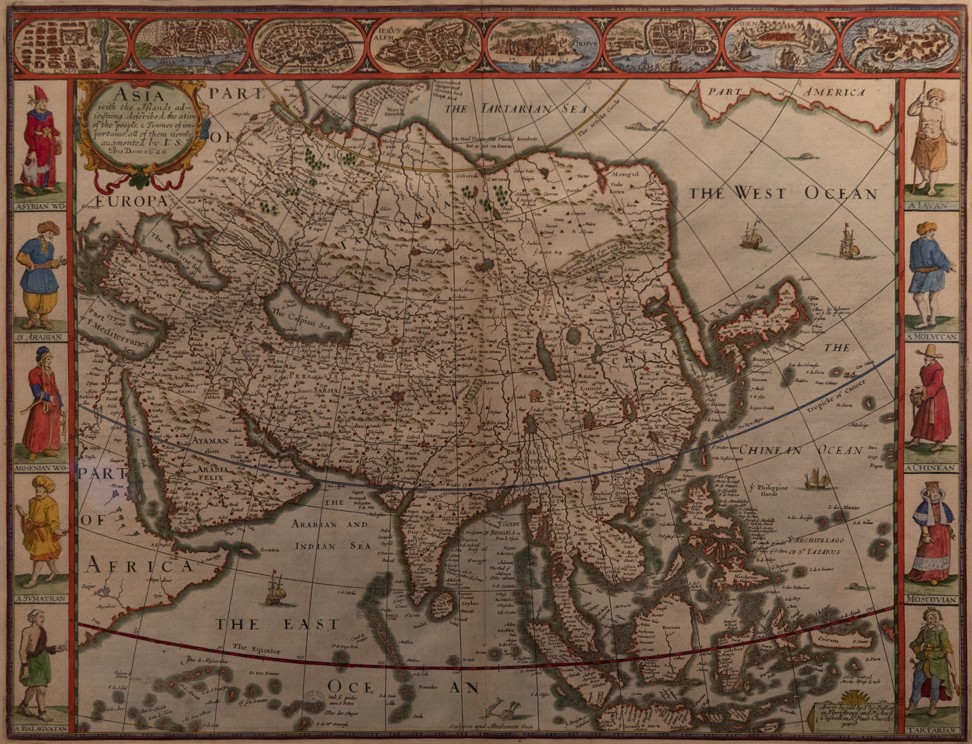

A map by Englishman historian and cartographer John Speed, published in 1676, at the exhibition, which includes depictions of indigenous people from major countries in the region.

Photo: Antony Dickson

Close-up of John Speed’s map, which shows a tall, white-bearded gentleman wearing a red monk’s robe and a large brown wide-brimmed cowboy hat described as a “Chinean” – revealing the paucity of information about China in the late 17th century.

The exception was maritime charts, which were needed to guide Chinese junks safely between ports.

One exhibition highlight is a beautiful nautical chart thought to represent the sixth voyage of the Chinese fleet of imperial treasure junks, commanded by Zheng He.

The Muslim admiral led seven diplomatic expeditions from China’s eastern city of Nanjing to the coast of east Africa between 1405 and 1433.

Though the chart depicts islands, harbours, navigational hazards and sailing routes, it was actually compiled some 200 years after Zheng He’s famous voyages were completed.

The expeditions described in the chart represented a high point in terms of official Chinese engagement with the barbarian world, though Tam notes that Zheng was not the first to sail between China and the Persian Gulf and eastern Africa.

Numerous sailors and merchants had been doing this since the eighth century – possibly earlier.

While Chinese junk captains traditionally hugged the coast, it was their Arab counterparts who held the key to celestial navigation – using the stars and planets to determine position and heading.

It is likely that Zheng employed experienced Arab mariners as pilots and that much of the information on the chart was derived from Arab sources.

Zheng is often cited as the historical symbol of the Maritime Silk Road, which is the inspiration for Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “belt and road” trade and diplomatic initiative.

However, the ancient chart suggests that China could not have navigated very far along the Maritime Silk Road without Islamic knowledge and technology.

It was the arrival of Western technology and knowledge introduced by European missionaries that persuaded the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) to undertake large-scale, detailed surveys of its recently expanded Chinese territory.

In 1708, the 47th year of the Kangxi reign, a team of Jesuit missionaries and scholars were recruited to undertake a comprehensive and highly ambitious cartographic survey of China and the surrounding region.

The map, which is called Huang Yu Quan Lan Tu (Kangxi Imperial Atlas of China), took more than 10 years to complete and covered all Chinese territory plus Tibet and the Korean peninsula.

According to Professor Mario Cams at the University of Macau, at the time this map was produced the Qing empire was almost at the height of its territorial reach.

It had conquered much of the vast Mongolian steppes and parts of Taiwan.

Qing China was sending armies into Tibet and towards the deserts in the far west – today’s Xinjiang region – and laying the foundations for the territory of the modern People’s Republic of China.

People walking past the “Complete Map of the Unified Great Qing” at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum.

Photo: Antony Dickson

The 41 sheets of the copperplate atlas together constitute one large map of continental East Asia, from Lake Baikal (north) to Sakhalin (northeast) and Taiwan (east), and from Hainan Island (south) to Kashgar (west).

It has sometimes been called the “Jesuit map of China”, but Cams says that title underestimates the contribution of Chinese officials and scholars.

This enormous atlas of Qing China, printed in several versions, resulted in the largest mapping project of the early modern world and is unique in a number of ways, Cams says.

First, it was largely based on field surveys conducted by mixed teams of Qing officials and European missionaries.

Second, it is probably the most important example of early modern state-sponsored cartography.

Third, it is a product of the creative integration of two different cartographic practices, European and East Asian.

Globes on display at the exhibition.

Photo: James Wendlinger

It was not until 1899 that China produced its first modern map without Western help and referenced to latitude and longitude with a conical projection, according to Tam, but the central meridian remained in Beijing.

Called the Daqing Huangyu Quan Tu (Imperial Atlas of China), the map is remarkable because the external land boundaries are deliberately left ambiguous, Tam says.

“So many Western powers wanted a slice of China [by this time] that they could not define their own boundaries because, diplomatically, China could not afford to upset any third-party power,” says Tam, standing by the 1909 edition of the map on display at the exhibition, which still has the purchase price of 1.20 Chinese dollars displayed in the bottom corner.

In less than a century, China had regressed from an empire under heaven, so self-confident that it did not feel the need to define its boundaries, to a nation that could not afford to define them for fear of upsetting aggressive foreign powers.

Tam says this was part of the process of the “100 years of humiliation” that still informs contemporary foreign policy in Beijing.

“I think it must influence modern Chinese diplomacy,” Tam says, adding that it may be one reason Beijing is still so sensitive about issues of sovereignty.

Maps, charts and globes on display at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum.

Photo: James Wendlinger

The first Chinese map with a complete border was not completed until 1905, as part of the self-strengthening movement to modernise and industrialise China to compete with Western hegemony.

Tam describes it as China’s “joining point with modernity”.

It is also apparent that while China needed Western and Islamic technology to inform its traditional view of the world, the Western view of China was distorted and inaccurate until relatively recently.

China is featured in Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published in 1570 and thought to be the first true modern atlas.

Many places in China are marked on this map, but the landscape is shown as a rectangle and some coastlines are wrongly drawn.

Meanwhile, a map of Asia by English historian and cartographer John Speed published in 1676 includes depictions of indigenous people from major countries in the region.

A tall, white-bearded gentleman wearing a red monk’s robe and a large brown wide-brimmed cowboy hat is described as a “Chinean” and reveals the paucity of information about China in the late 17th century.

“Maps and charts offer a new dimension and angle on Chinese history,” Tam says.

Links :

- SCMP : The South China Sea: Conflicting Claims

- GeoGarage blog : Collector's 400 years of China maps and nautical charts up for ... / New map boosts China's maritime claims / Ancient map irrefutable evidence that the ... / Battle of the South China Sea charts / China revises mapping law to bolster claims ...

No comments:

Post a Comment