source : MarineTraffic

From The Economist by G.D.

Immigration checks are almost non-existent, but turbulent waters bring other problems

Stand on Britain’s southern shore, looking towards France, and your gaze will settle upon the world’s busiest shipping lane.

Over 600 cargo ships pass through the English Channel each day.

A maritime version of Guernica realized by Javcho Savov

Many are heading to and from London or Rotterdam, separated by what amounts to a motorway-style central reservation that they may not cross (see image).

Adding to the traffic are more than 60 daily cross-Channel ferry services, as well as fishermen and private recreation vessels that can number in the thousands on a summer weekend.

To date, only small numbers of migrants have tried to reach Britain this way, but their numbers are rising: 539 migrants attempted the journey last year, according to figures from the Home Office, but around 80% of these attempts were made in the last three months of 2018.

Is Brexit driving the surge in migrants crossing the English Channel by boat?

photo : AFP

What are the risks and rewards of making the crossing?

The risks are clear: this is a testing crossing even for an experienced sailor with a seaworthy boat.

It is not just maritime collisions that skippers have to think about.

Tides in the Channel are among the biggest in the world.

The island of Jersey has a maximum tidal range of over 12m (39ft).

At low tide up to 3km of beach and rock can be exposed.

The channel goes from 240km at its widest point to 33km at its narrowest, which is why tidal races such as the Alderney Race, a strait just off the Cotentin Peninsula of France, or the waters just off Portland Bill near Weymouth are so notorious.

These can create treacherous seas even on the calmest of days.

Then there are sandbanks, shoals, isolated rocks and other dangers to negotiate—and that’s before the weather plays its unpredictable part.

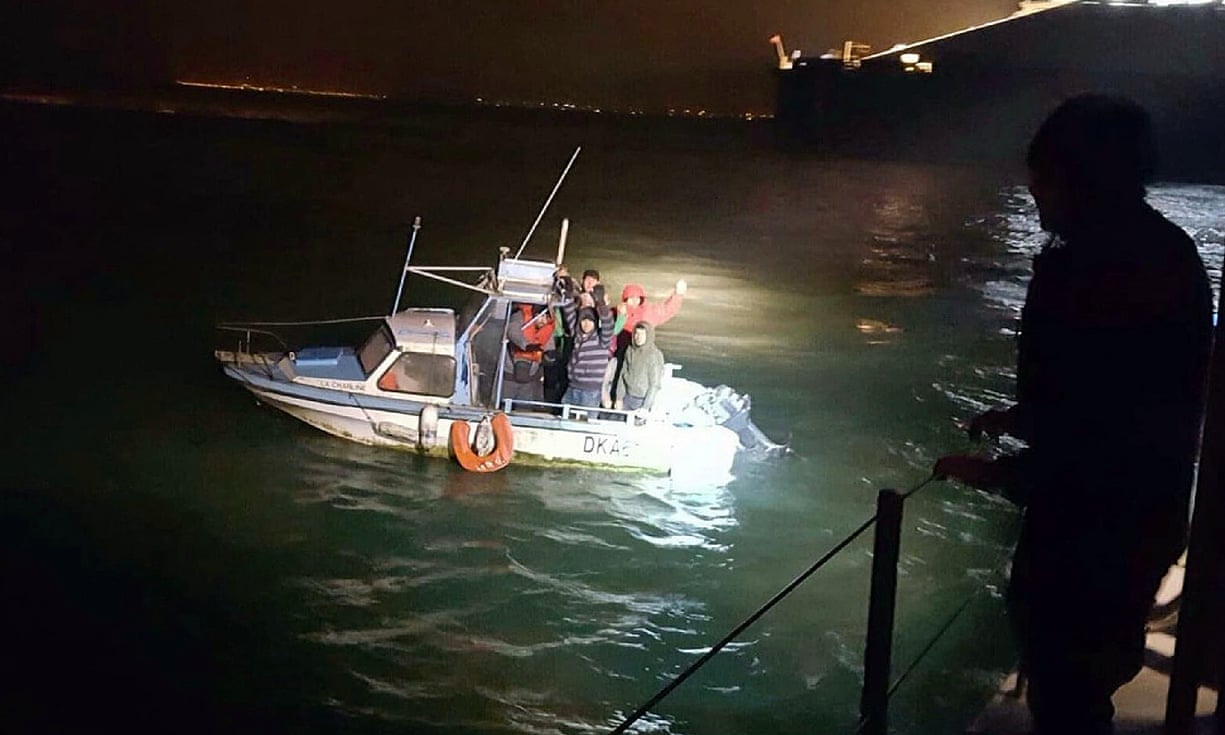

Iranian migrants being picked up by the Gendarmerie Maritime in Calais.

Photograph: Gendarmerie Maritime

Yet for migrants and traffickers this particular route also has a definite upside.

Perhaps because of longstanding assumptions about the sea’s effectiveness as a barrier, there is little in the way of security controlling the movement of pleasure craft.

Many hundreds of ports along Britain’s south coast can be entered by small boats, which are greeted by little more than a poster (see image) suggesting that a phone call to the authorities or the national yachtline may be required to declare the immigrant status of certain sailors.

Official ports of entry such as Portsmouth or Southampton are for ferries and commercial traffic and a world away from an unmanned wooden jetty or marina berth where people come and go at all hours.

The traditional flag etiquette for those arriving from a foreign trip was to fly a yellow quarantine (Q) flag before getting the all-clear from officials who would check on travellers’ health and customs matters.

The flying of the flag is still a requirement for ships coming to Britain from outside the EU (owing to concerns about disease more than migrants), but small boats do not always adhere to the rule.

And a craft registered within the EU and wishing to enter another EU port need not show the Q flag at all, so there is no indication whether it has come from abroad or from just up the coast.

On many occasions your correspondent has enjoyed a breezy daytime crossing, a berth in a French port, steak frites on shore, and a jaunt back home the next day, with never a form filed or passport asked for.

Britain

will recall two overseas border patrol boats in response to a spike in

migrants attempting to cross the English Channel in dinghies.

Britain’s Border Force has four cutters that are unlikely to patrol en masse in the Dover Strait.

They may not be enough.

Links :

- DailyMail : Border Force catch nine migrants off Dover coast bringing total attempting Channel crossing to 44 in two days

- SkyNews : Rough crossings / Dozens of migrants picked up crossing Channel in boats

- CNN : Migrants risk death at sea to reach Britain as prices spike on traditional routes

- The Guardian : Channel migrant crossings: who is coming and why?

No comments:

Post a Comment