HMS Enterprise H88, a Royal Navy 'Echo' Class Hydrographic Oceanographic Survey Vessel

3 years on operations traveling over 150,000 Nm and visiting 20 countries,

equivalent of circumnavigating the globe 7 times

(pictured alongside at the port of Kristiansund, Norway)

From The Register by Gareth Corfield

Warships don't only sink the nation's enemies, you know

You may think of a warship as a vessel that sails the Seven Seas, bristling with missiles and guns, ready to deal out death and destruction to Her Majesty's enemies.

In fact, warships do many other jobs too – such as HMS Enterprise's routine but vital task of seabed surveying.

Your correspondent spent most of last week aboard the Enterprise, boldly going from Kristiansund to Trondheim via the Arctic Circle.

I was welcomed aboard by the ship's captain, Commander Phil Harper, a veteran sailor with 28 years of Royal Navy service.

Cdr Harper was proud to tell me what his ship does: seabed survey.

This means sailing around designated parts of the world's oceans and using different types of sonar to find out how deep it is and precisely what lies beneath.

While the majority of the sea looks like this...

A relatively calm Arctic Sea, with the USS New York as a distant blot on the horizon

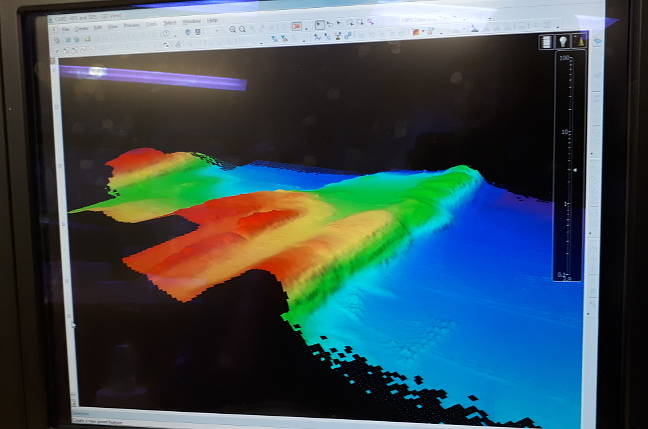

... underneath, it can be just as dramatic as the Grand Canyon:

A portion of the Norwegian seabed, as scanned by the ship's sonar

"It needs constant updating," said Cdr Harper, referring to the maritime charts that tell seafarers where they are and how deep the water is underneath their ships.

"Just 10 per cent of the world's oceans have been surveyed."

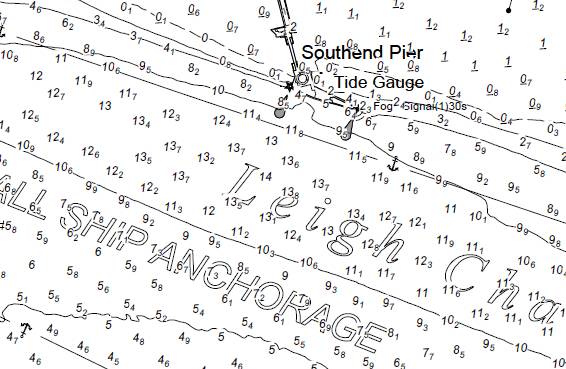

Much like the way a hiker will have a map of the area he intends to walk over, complete with contour lines and points of interest marked on the map, seafarers also need similar maps, or charts.

Modern technology hasn't advanced too far beyond the age-old concept of sending a ship and her crew out to survey a particular part of the sea.

A sample of a British nautical chart, in this case prepared by the Port of London Authority for the area covering Southend Pier.

The big numbers are depth in metres; the small ones decimetres (tens of centimetres).

Contour lines are drawn on at intervals.

On UKHO charts, colours are used for different contours to aid depth perception.

Southend Pier with the GeoGarage platform (UKHO nautical chart)

Southend Pier with the GeoGarage platform (UKHO nautical chart)

During a comprehensive tour of Enterprise's survey data processing gear, one of her hydrographers, Petty Officer Adam Coleman-Smith, explained: "The Hydrographic Office (UKHO) develops the ship's tasking, the areas she goes to."

Broadly speaking, the British government's maritime charting agency, the UKHO, tells the Navy's three-strong survey fleet what parts of the world's oceans need surveying.

Along with her sister ship HMS Echo and the new inshore survey vessel HMS Magpie, the ship is equipped to scan the seabed and generate reams of data that the UKHO turns into its famous Admiralty charts.

Enterprise herself carries a Kongsberg EM-710 multibeam sonar, capable, as PO Coleman-Smith described, of putting out 254 separate sonar beams to scan the seabed.

Unlike her sister ships in the Navy's mine-sweeping flotilla, which also use sonar for detecting items under water, PO Coleman-Smith said: "Whereas the minehunters are looking for object detection, we're looking at safe navigation."

The ship also carries a sound velocity probe, which is winched out of her Baltic Room and lowered until it is just above the seabed, with operators taking readings at intervals of what the hydrographers call the water column, which is the area of water directly beneath Enterprise.

The three-foot SV probe is lowered from Enterprise into the icy waters of the Arctic

A straightforward affair in the calm seas of an early Arctic afternoon – if it's too choppy then the device cannot be deployed.

Underwater physics – rocket scientists, eat your hearts out

When surveying a particular piece of the ocean, Enterprise's crew works out survey lines for the ship to follow.

She then sails up and down those lines with the sonar switched on, having first ensured no marine wildlife is nearby that would be distressed by the sonar.

Thanks to physics, "the deeper the seabed, the more coverage you get".

At its simplest, seabed sonar works by transmitting a sonar pulse from the unit slung below Enterprise's hull.

The sound wave reflected from the seabed is received by the unit, meaning you can work out the depth from the time taken for the wave to reach the seabed and return to the ship.

So far, so simple: the speed of sound in water is 1,500m/s, as Cdr Harper told me.

It gets more complex when you consider the physics of sea water.

Unlike your bath, the sea is not homogenous; it is salty, some areas more so than others, and its temperature varies.

HMS Echo: the survey ship and her role

"Have you heard of the afternoon effect?" asked Cdr Harper, going on to explain that during the Second World War, naval analysts noticed that many fewer enemy submarines were detected in afternoons when compared to mornings.

This is because the sun heats the upper few metres of the sea.

At the point where that heating effect ends, you get a change in water density.

That also causes a change in the speed of sound through the water, which refracts the sonar's sound waves in a slightly different direction.

Instead of tracing a nice straight line from seabed and back, the sound waves emitted by the sonar bend at that density change point, like how a straw in a half-full glass of water looks "bent".

In turn, that means you need a computer and software which can calculate precisely how much those waves have bent.

Coleman-Smith described the "tidal stream data, DGPS, temperatures, salinity" and more that Enterprise's systems take into account when figuring that out.

"It's all algorithms, really."

Doing that needs a fair amount of computing grunt available: while the ship's onboard IT runs a motley collection of early 2000s operating systems, your correspondent noted one of the survey department's data-crunching machines had a whopping 128GB of RAM available to it.

Cdr Harper said: "It's nearly terabytes we are looking at uploading now.

Back in 2012 we were sending off one or two hard drives of up to a GB each."

Enterprise turning at the end of a survey line, while somewhere in the Arctic

Just to make sure, when surveying, Enterprise doubles up on each survey line ("200 per cent coverage," said Coleman-Smith) in order to gather the best available data for her surveyors to tease out the anomalies.

Thanks to her differential GPS fit, the ship can achieve a positional accuracy of 20cm, sailing at speeds of 6-8 knots (nautical mph).

While all the data processing gear is highly technological, Coleman-Smith is philosophical about the future being automated and free from humans.

"I can't see in my time it needs fully replacing.

You still need to program the missions and you still need to download it when the craft return.

It's still not autonomous.

As surveyors, our autonomous underwater vehicles do not give us that accuracy we need because they don't take a GPS reading with them."

He stood, rooted to the floor of the survey chart room as the ship rolled over a wave like an elephant getting out of bed, sending both a chair and your correspondent flying from one end of the compartment to the other.

"You'll still need people there."

Not all the seabed surveying is about finding underwater mountains, though.

Coleman-Smith told us that in 2012 "I found a landing craft down there" in Weymouth harbour, which meant "we had to raise a notice to mariners" warning sailors not to sail over that spot or drop anchor on it.

He added: "You've got HMS Hood [the First World War era vessel] down there, she was sunk deliberately to block entrances."

It's a broad and varied job, charting the oceans - and definitely not the sort of thing you normally associate with the term "warship".

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment