:focal(512x385:513x386)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/e5/59e5589d-51cb-4cb2-bedb-95fe374c9292/searle_2in_deepworker_copy_tim_taylor.jpg) Marine Biologist Sylvia Earle in a DeepWorker submersible.

Marine Biologist Sylvia Earle in a DeepWorker submersible.Tim Taylor, Mission Blue

For International Women and Girls in Science Day, the museum’s Ocean Portal spoke with “Her Deepness” about science, seaweed and the planet’s future

Hidden from public view at the National Museum of Natural History is a massive room filled with rows and rows of storage shelves.

Each holds stacks of thousands of herbarium sheets – dried samples of plant species from around the world.

Within this sprawling assemblage of plastered plants is a set of algae sheets with a very important history — they are the life’s work of Sylvia Earle.

This past November, “Her Deepness” returned to the museum and visited the specimens she collected half a century ago.

Earle is one of the great naturalists of the last century, often mentioned among the likes of David Attenborough and Jane Goodall.

She was the first woman to lead the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, holds the record for the deepest untethered dive and has led countless expeditions across the globe.

One of her most famous missions was leading an all-female expedition inside the Tektite Habitat, an underwater laboratory, during a time when women were often excluded from similar opportunities.

Born in 1935, Earle continues to passionately advocate for ocean conservation.

In 1999, Earle donated her life’s work to the museum, which is home to the United States National Herbarium.

She felt it was important that her specimens remained preserved in the “central headquarters for keeping the history of life intact.” The Earle collection includes over 6,000 herbarium sheets with meticulously preserved algae and seagrass specimens from across the globe.

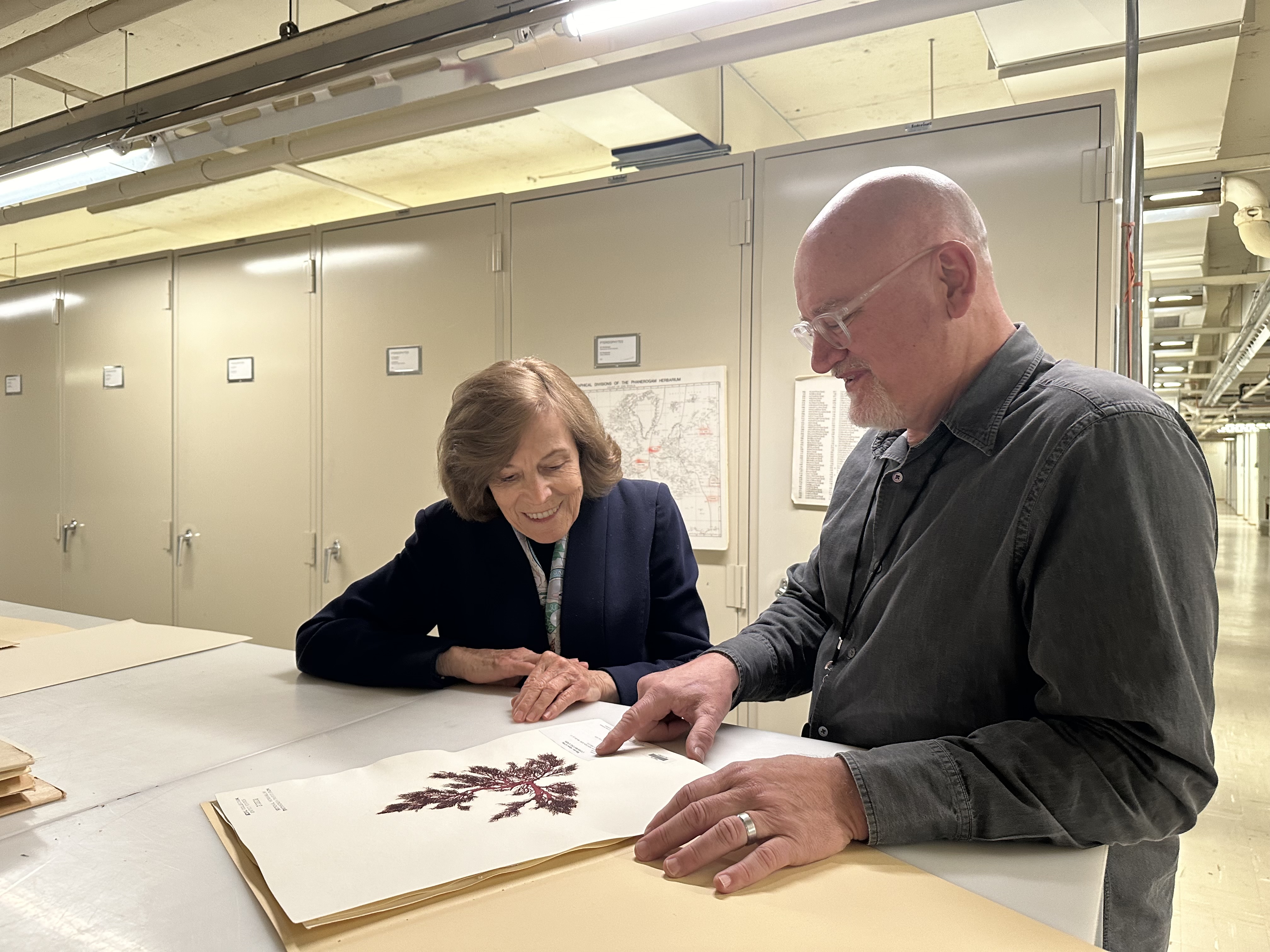

Earle (left) speaks with Danielle Olson in the National Museum of Natural History’s collection space in late 2024.

Emma Saaty, NMNH

During her 2024 visit, Earle had a chance to sit down with Danielle Olson, the managing editor of the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal.

As a child Olson dressed up as Earle for a school wax museum project and, like many young girls, she was inspired by Earle to pursue a career in the marine sciences.

In the interview below, Olson asked Earle about her pioneering career and some of the seaweed she has collected along the way.

The following is from their discussion and has been edited for length and clarity.

Danielle Olson (DO): Your parents instilled a love for the ocean and the natural world.

Why did you gravitate toward algae?

Sylvia Earle (SE): Why not? I had my eyes opened to the amazing diversity, beauty, wonder and importance of the photosynthesizers in the sea, what we call seaweeds or algae and seagrasses, by my major professor Harold Humm during a summer class in marine biology at Florida State University.

We literally immersed ourselves in the ocean.

Harold’s passion for seaweed was contagious.

I think I was the only one of the eight students who stuck with it.

I had already been splashing around a bit in the Gulf of Mexico but had not appreciated the seagrasses and algae.

I was initially more intrigued by the fishes and invertebrates— the crab and the sea cucumbers—and other things where I lived in Clearwater Bay.

DO: Using scuba gear to conduct research was very new when you did your PhD work.

What went into your decision to use the gear and how did that affect what you were able to do?

SE: Before I even started my doctoral program, it was difficult to find out who knew what about life in the Gulf of Mexico.

There was one publication in 1954 that tried to pull together as much as was then known about the [Gulf’s] biology, geology and the currents and tides.

A very small portion was about marine plants and algae written by William Randolph Taylor, which summarized all that was known then.

It wasn’t very much.

Most was derived from what could be either dragged from the ocean using a net or trawl or picked up off the beach.

People just did not get into the water.

Having a facemask and fins, that was in itself a breakthrough.

But scuba had also come along.

That class I took in marine biology in the summer of 1953 was my first introduction to scuba.

Harold Humm had somehow managed to get two of the first scuba tanks with regulators that were intended for Navy diving, which we used for the summer class.

We also had a compressor that had a cable attached to it with a mask and a regulator.

The compressor stayed on the surface on the boat and one person at a time could dive down to the length of the hose.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/a4/58a4a2a7-0369-4c0b-a1c0-a5d636ffdbb6/sylvia_earle-nur08002.jpg) During a dive, Earle (left) displays samples to a colleague inside a submersible.

During a dive, Earle (left) displays samples to a colleague inside a submersible.NOAA Photo Library

The beauty of scuba is that you’re free.

It was transformative for me.

Before I could take a breath and stay down for half a minute.

But with scuba, I could stay [underwater] longer and go deeper.

The biggest breakthrough as far as I’m concerned was the facemask, so that you could see clearly underwater.

It makes all the difference.

The next big breakthrough was being able to breathe underwater.

Unlike my predecessors who were exploring the Gulf of Mexico looking at seaweeds [at the surface], I could actually see where they were growing.

Like taking a walk in a forest, I could stroll through these underwater gardens.

It was the first time, literally, that anyone was at the places that I was diving.

DO: You have been studying the ocean for roughly 7 decades.

What are some key takeaways you’ve learned over that time?

SE: So little of the ocean is explored.

It’s easy to find new species underwater.

It’s easy to find new species underwater.

It’s a mystery to me that in the twenty first century it is obvious that the ocean dominates the Earth — without the ocean, life could not exist — and yet we take it for granted.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/70/c070947c-2154-4b6b-a770-a9bee4851e0a/president_barack_obama_visits_midway_atoll_-_dpla_-_3b1620f7acd0163b3f1e77a4cb9476a4.jpg) Earle speaks with President Barack Obama during a 2016 visit to Midway Atoll.

Earle speaks with President Barack Obama during a 2016 visit to Midway Atoll.Earle is holding a photo of a recently discovered species of fish native to Midway waters.

Barack Obama Presidential Library

or anyone who has been around for a while and paying attention, it’s obvious that we have displaced, consumed and otherwise lost so much of the [terrestrial] system.

The ocean has not been as obvious, but it has been as comprehensive.

We have a different attitude about ocean life and land life.

I think everyone should know what air is, know the basics of what keeps every one of us alive.

We live on a miracle.

Earth is a miracle.

Look around the universe, there is nothing like Earth and nothing like what we take for granted, the ocean.

It’s a living ocean, not just rocks and water.

It has taken 4.5 billion years to form this planet into what we take for granted today.

Much of the heavy lifting, in terms of turning rocks and water into a habitable planet has been made possible by the creatures we call algae.

DO: I want to talk about your algae collection.

Where are some of the places that you collected?

SE: From Chile, Ecuador, California and Alaska.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1d/b7/1db76319-dd2f-4fff-a719-d398ab6f9485/ark__65665_m373b5da2789374a8a952fcb2190c1b133.jpg)

An algae specimen from the herbarium that Earle collected in 1966 near Santa Barbara.National Museum of Natural History

Algae — they are ancient.

They go back in time long before there were dinosaurs, before there were fish.

We’re talking half a billion years ago [these algae arose], and they are still in reasonably unchanged form.

Some are the green algae that form a calcareous matrix that enables them to be preserved as fossils, others are soft and haven’t been retained.

[Algae are] the forms of life that have helped shape the planet into a habitable place, and we should show them some respect.

DO: How do you hope your collection will be used by future scientists?

SE: I regard myself as a witness to change over time.

I experienced decades of change.

Some of the changes are really good and some of them are not so good.

I have lived the better part of a century.

The collections are like a silent witness to this change, and they will persist far beyond my time.

They are a record life as it is now and as it was decades ago.

If others keep this tradition of maintaining a record of life, it will be one of the most valuable records of insight that we have.

You cannot extract DNA from a photograph.

We have taken pains over the ages to take a reference piece of the environment and tuck it away so that at any time in the future, we can ask new questions that we don’t even know how to answer today.

If you don’t have knowledge of the past, it is hard to understand the present let alone anticipate the future.

Algae — they are ancient.

They go back in time long before there were dinosaurs, before there were fish.

We’re talking half a billion years ago [these algae arose], and they are still in reasonably unchanged form.

Some are the green algae that form a calcareous matrix that enables them to be preserved as fossils, others are soft and haven’t been retained.

[Algae are] the forms of life that have helped shape the planet into a habitable place, and we should show them some respect.

DO: How do you hope your collection will be used by future scientists?

SE: I regard myself as a witness to change over time.

I experienced decades of change.

Some of the changes are really good and some of them are not so good.

I have lived the better part of a century.

The collections are like a silent witness to this change, and they will persist far beyond my time.

They are a record life as it is now and as it was decades ago.

If others keep this tradition of maintaining a record of life, it will be one of the most valuable records of insight that we have.

You cannot extract DNA from a photograph.

We have taken pains over the ages to take a reference piece of the environment and tuck it away so that at any time in the future, we can ask new questions that we don’t even know how to answer today.

If you don’t have knowledge of the past, it is hard to understand the present let alone anticipate the future.

Earle and Barrett Brooks, a botanical researcher at the museum, examine one of Earle’s algae specimens in the National Herbarium.

Earle and Barrett Brooks, a botanical researcher at the museum, examine one of Earle’s algae specimens in the National Herbarium.Danielle Olson, NMNH

Going back to when I began exploring the ocean, we did not have the technologies that now enable us to go deeper and explore longer.

To have the kind of insights that we take for granted on land.

You can go camping in the desert or climb mountains.

In the ocean if you are going to study mountains you start at the top and you work your way down.

The deeper you go the less we know.

This is the most exciting time right now.

I am thrilled at what I was able to gather in my early years as an oceanographer, botanist, seaweed person, ecologist, whatever you want to call it — it has an enduring value.

We really need the physical evidence.

DO: Which algae are your favorite?

SE: My favorite ones are the living ones.

I feel that sense of wonder every time that I am privileged to get out there and down there.

You realize that you are looking at living history.

The creatures who are here peacefully changing rocks and water into a habitable planet for the likes of us.

They are still here; I can still salute them.

"If you don’t have knowledge of the past, it is hard to understand the present, let alone anticipate the future." — Sylvia Earle

DO: There are many women inspired to study the ocean due to your success.

How does that make you feel?

SE: I realize that there is a gender mismatch in terms of opportunity, but there are so many reasons why people will tell you that you can’t do something.

You’re too tall, you’re too short, you speak the wrong language, the color of your skin doesn’t suit the job we have in mind.

There are plenty of excuses for why you can say “I can’t do this.” Somehow, we must get over excuses and get on with it.

And I just did.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9e/30/9e30752f-fad3-4cbd-b074-b349e7f96f1c/sylvia_earle-nur09015.jpg) Earle (far right) and the rest of the all-female Tektite team learn how to use a rebreather in 1970.

Earle (far right) and the rest of the all-female Tektite team learn how to use a rebreather in 1970.NOAA Photo Library

I wanted to be a part of the team of aquanauts that lived underwater, but I couldn’t go with the team that I originally planned to because it was men and women living together underwater, which was not acceptable [at the time].

But instead of giving up I changed direction and instead we had a team of just women.

Nobody planned that in advance, but it evolved as a solution to what seemed to be a gender problem.

There are so many ways to go around, under or sometimes right through.

DO: What advice do you have for aspiring marine scientists?

SE: Go for it.

Don’t let anyone steal your dream.

Don’t be afraid to be first, somebody has to get out there.

One of the best reasons to go do something is because nobody has done it before.

Links:

No comments:

Post a Comment