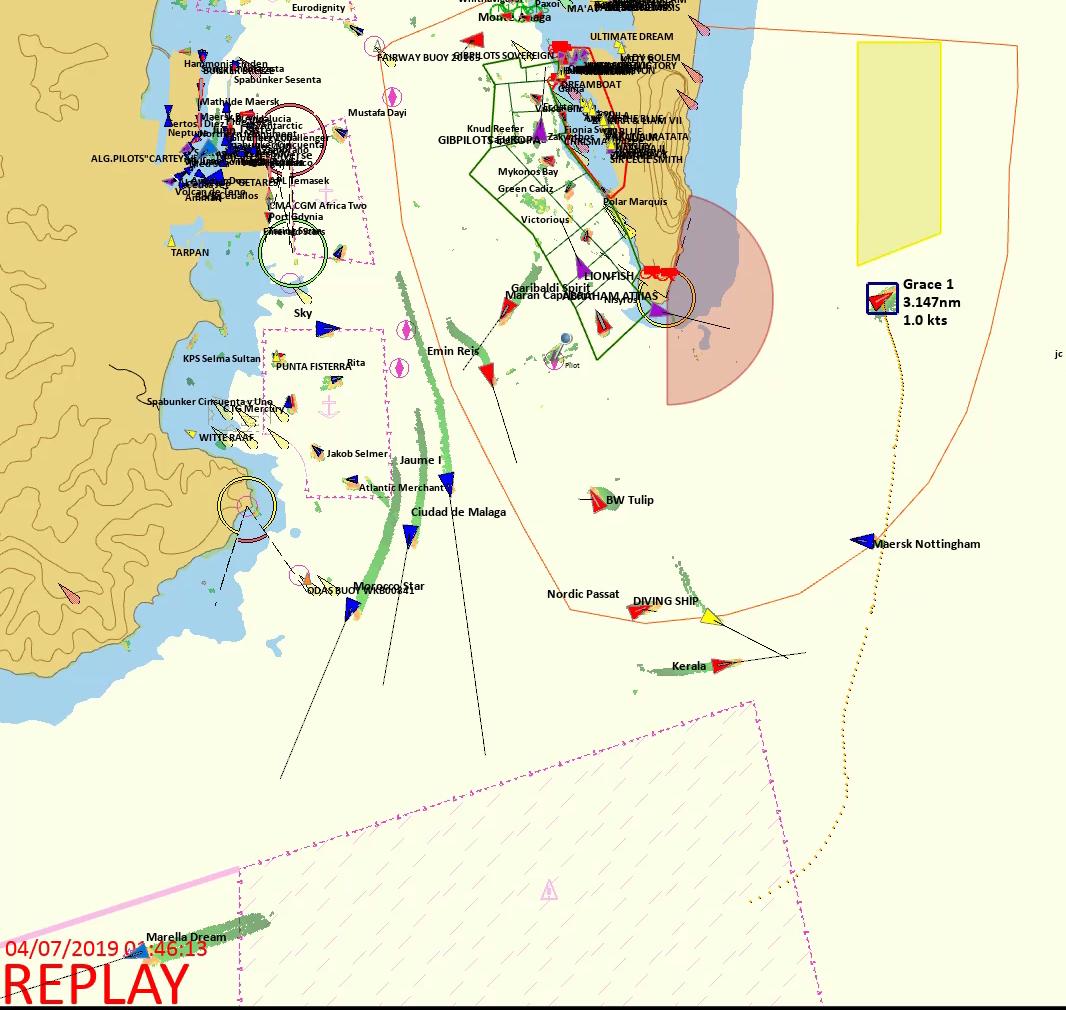

A British Royal Navy patrol vessel guards the oil supertanker Grace 1, that’s on suspicion of carrying Iranian crude oil to Syria, as it sits anchored in waters of the British overseas territory of Gibraltar, historically claimed by Spain, July 4, 2019.

From Windward by Omer Primor

Panamanian flag, Singaporean manager, Iranian oil: six words and three countries that tell the multinational story of the Grace 1, the oil tanker detained in Gibraltar by the UK earlier this week for violating EU sanctions.

Less than 24 hours later, Tehran admitted being the real owner of the vessel carrying some two million barrels of sanctioned, Iranian oil, disguised as being of Iraqi origin.

The supertanker Grace 1 off the coast of Gibraltar, on July 6, 2019.

AFP

But the case of the Grace 1 is about more than just Iran.

It goes to the heart of the challenges of enforcing sanctions today.

The rules of the game have changed, and those attempting to evade sanctions are increasingly doing so using “innocent” ships.

Gone are the days of sanctioned trade being carried by the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC), or by vessels flying the North Korean flag.

In the past 60 days, Iranian-flagged tankers made less than a handful of port calls outside their home country.

North Korean tankers had none.

Ties to Iran

So what exactly were the Grace 1’s ties to Iran? Investigating its ownership would lead nowhere.

According to Equasis, it is owned and managed by Singaporean companies, its real, beneficial owner remains unknown, passing screening against databases of sanctioned entities (such as SDN lists) and rules relating to the country of registration.

Grace 1 Ownership Details. Source: Equasis

Ownership databases also show a connection between the Grace 1’s registered owner and manager: both are listed under the same address in Singapore.

In fact, the two share contact information with three other companies, each listed as a registered owner of a ship managed by the same manager.

Going beyond ownership to investigate the vessel’s port calls and historical locations would also lead to a dead end.

The Grace 1 was last detected in port almost two years ago, in Qingdao, China.

Since then, it’s been operating continuously at sea; any port calls it may have made have been masked by turning off its mandatory AIS transmissions.

The Grace 1’s recent history of port calls: Source: Windward

Grace 1 of Many

What’s perhaps even more troubling is that the Grace 1 isn’t alone.

In May, 19 crude oil tankers (3% of all crude tankers operating in the Gulf) went dark while operating in the area, behavior indicative of sanctions evasion.

While eight of those were Iranian flagged and obviously a no-go for trade, the other 11 aren’t as easy to screen: seven were Panamanian, two Liberian and two Vietnamese.

None of them is registered by an Iranian Company or made port calls in Iran, making them almost impossible to detect using existing vessel tracking and list-based screening.

Image showing 18 dark activities by the 11 tankers in May.

Source: Windward

What’s more, these 11 tankers went on to make 68 ship-to-ship meetings offshore Fujairah, in the UAE, in May-June.

There, they received logistical support and transhipped cargoes to other tankers.

In one incident, a crude carrier picked up cargo from the Grace 1 offshore Fujairah and carried it to Singapore, very possibly without knowing cargo’s origin.

Image showing 68 ship-to-ship meeting offshore Fujairah in May -June by the 11 tankers.

Source: Windward

As with the recent case of the Pacific Bravo, the use of front companies, transshipments, dark operations, and identity changes creates new risks for the entire maritime supply chain – ports and terminals, traders, bunkering services providers, financial institutions, and even governments – which are now required by OFAC to go beyond existing vessel tracking and list-based screening.

Shipping has always been a complex industry.

Tax structures and other considerations dictate the use of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) for ownership of every vessel.

It’s clear the vast majority of players aren’t interested in trading in sanctioned cargoes.

However, at a time when the business climate is becoming increasingly complex, and with so much attention on every ship movement and every cargo, many companies are left wondering how should they implement these new regulations – especially when existing compliance controls are losing their effectiveness at a rate of knots.

Refinitiv Oil Research has been tracking the Iranian VLCC Grace1

. She departed Iran on 17/04 and remained floating off UAE for 23 days before departing on 13/05. With no access to SUMED she had to pass around the Cape

source : Refinitiv

Grace 1 tanker movement between Iraq, Iran and the UAE

source : CTRM center

Business as Usual

So what can the maritime ecosystem do in order to keep business running as usual? The strongest signals indicating vessels may be violating sanctions come from behavioral analysis.

For the Grace 1, the signs have been there for at least six months – almost coinciding with the November reimposition of sanctions by the U.S.

For example, from mid-December 2018 to mid-January 2019 the ship anchored offshore Asaluyeh, Iran.

In April, it went dark for 10 days near Bushehr, also in Iran.

Image showing the Grace I anchored offshore Asaluyeh, Iran,

for a month, Jan. 2019.

Source: Windward

Behavioral analytics is key to effectively screening against vessels potentially engaged in sanctions evasion.

Even the best tools that screen against lists, port calls and ownership data fall short when they come up against today’s elaborate schemes employed by those interested in evading sanctions.

Links :

- Euronews : Iranian cleric says UK should be 'scared' of Tehran's response over ...

- CNN : Gibraltar seizes Iranian oil tanker bound for Syria / Adviser warns Tehran could seize UK oil tanker if Iranian ship not ...

- The Guardian : Iran fury as Royal Marines seize tanker suspected of carrying oil to Syria

- Aljazeera : BP oil tanker sheltering in Gulf over fear of Iran attack

- Teheran Times : Seizing Grace 1 tanker: An outright theft with no legal justification

- Bloomberg : What's Next for the Oil Tanker Seized by British Forces

- The Times : BP oil tanker sheltering in Gulf amid fears it could be seized by Iran

- Business Insider : A seized Iranian tanker took a several-thousand-mile detour around Africa in a possible attempt to sneak a shipment of crude oil to Syria

- Lloyds : Gibraltar tanker seizure triggers Iran-UK diplomatic row / Iranian tanker seizure could face legal challenge, say shipping lawyers

No comments:

Post a Comment