Watch as surface and subsurface ocean temperature anomalies in the Pacific

show the rise and fall of an El Niño.

NASA Earth Observatory visualization by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Global Data and Assimilation Office.

Caption by Mike Carlowicz.

Note: The following is an excerpt from El Niño: Pacific Wind and Current Changes Bring Warm, Wild Weather.

The ocean is not uniform.

Temperature, salinity, and other characteristics vary in three dimensions, from north to south, east to west, and from the surface to the depths.

With its own forms of underwater weather, the ocean has fronts and circulation patterns that move heat and nutrients around its basins.

Changes near the surface often start with changes in the depths.

Spanning one-third of Earth’s surface, the tropical Pacific Ocean receives more sunlight than any other region on Earth, and much of this energy is stored in the ocean as heat.

Under neutral, normal conditions, the waters near southeast Asia, Indonesia, and Australia are warmer and sea level stands higher than in the eastern Pacific; this warm water tends to get pushed west and held there by easterly trade winds.

But every two to seven years, this pattern is disrupted.

During El Niño events, the surface waters of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean become significantly warmer than usual and wind patterns change.

Easterly trade winds (which usually blow from the Americas toward Asia) falter and can even turn around into westerlies.

This allows great masses of warm water to slosh from the western Pacific toward the Americas.

The arrival of this warm water reduces the upwelling of cooler, nutrient-rich waters from the deep—shutting down or reversing ocean currents along the equator and along the west coast of South and Central America.

The “western Pacific warm pool” and the waves that propagate from it can extend down to 200 meters in depth, a phenomenon that can be observed by moored or floating instruments in the ocean: satellite-tracked drifting buoys, moorings, gliders, and Argo floats that cycle from the surface to great depths.

These in situ instruments (more than 3,000 of them) record temperatures and other traits in the top 300 meters of the ocean.

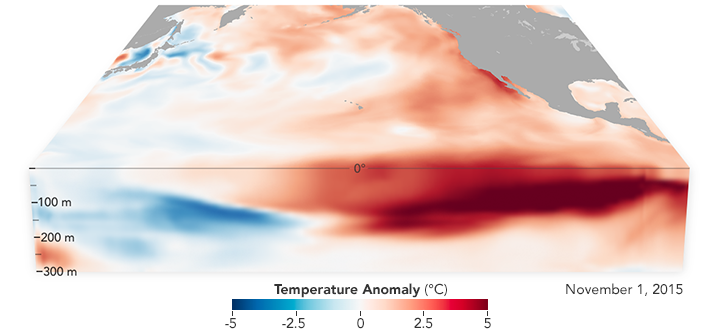

The still image at the top shows a cross-section of the Pacific Ocean in November 2015, near the peak of the most recent El Niño event.

Based on data from the Global Data and Assimilation Office, the map shows temperature anomalies; that is, how much the temperatures at the surface and in the depths ranged above or below the long-term averages.

The animation shows the changes in the Pacific from January 2015 through December 2016.

Note the warm water in the depths starting to move from west to east after March 2015 and peaking near the end of 2015. (The western Pacific grows cooler than normal.)

By March 2016, cooler water begins moving east, sparking a mild La Niña in the eastern Pacific late in 2016, while the western Pacific begins to warm again.

Data collected Feb. 28 - March 12, 2017, by the U.S./European Jason-3 satellite show near-normal ocean surface heights in green, warmer areas in red and colder areas in blue.

Ocean surface height is related in part to its temperature, and thus is an indicator of how much heat is stored in the upper ocean.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

El Niño’s episodic shifts in winds and water currents across the Pacific can cause floods in the South American desert while stalling and drying up the monsoon in Indonesia and India.

The atmospheric circulation patterns promote hurricanes and typhoons in the Pacific while knocking them down over the Atlantic.

Fish populations in one part of the ocean might crash, while others thrive and spread well beyond their usual territory.

El Niño is one of the most important weather-producing phenomena on Earth, a “master weather-maker,” as author Madeleine Nash once called it.

Learn more about the phenomenon in our feature story El Niño: Pacific Wind and Current Changes Bring Warm, Wild Weather.

Links :

- Phys : Could leftover heat from last El Nino fuel a new one?

- Washington Post : The unnamed phenomenon behind Peru’s extraordinary flooding

- New Scientist : Indian Ocean version of El Niño behind drought in East Africa

- The Guardian : Australia placed on El Niño 'watch' as weather bureau puts chance at 50% for 2017

- GeoGarage blog : El Niño unveiled in incredibly detailed animation / La Niña might not be coming after all / One year time lapse of the 2015-2016 El Niño event / Environmental records shattered as climate change ... / NASA examines El Niño's impact on ocean's food source / The strongest El Niño on record may be brewing in the ... / Studying the heart of El Niño, where its weather begins / A still-growing El Niño set to bear down on U.S.

NASA : 2015-2016 El Niño Provided ‘Natural Experiment’ on the Effects of Warming Seas

ReplyDelete