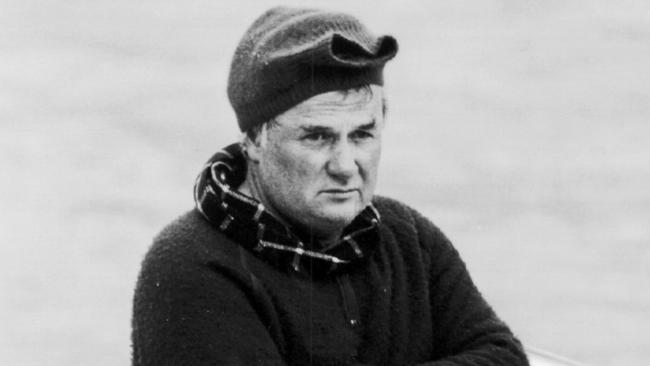

Illustration of John Quinn overboard Ale+Ale/Morgan Gaynin

From Sailing World by Mark Chisnell

How John Quinn survived nearly six hours in the Bass Strait and lived to tell about it is a miracle, but in the miracle there are lessons.

In Sydney, Australia, it’s called a southerly change, and it does what it says on the tin.

It’s a shift from a northeasterly summer sea breeze to a southerly wind, often driven by the arrival of a cold front and an associated low-pressure system sweeping up from the Southern Ocean.

The waves meet the shallowing floor of the Bass Strait, and the southerly wind meets the East Australian Current, flowing south at around 2 knots along Australia’s east coast.

The combination can make the ocean off the southeastern tip of Australia one of the roughest pieces of water in the world.

And as it’s about halfway between Sydney and Hobart, the words “southerly change” can have an ominous ring for sailors preparing for the start of the annual Sydney Hobart Yacht Race.

John Quinn was lucky to survive after he fell overboard during the 1993 race.

“When we saw the race [weather] briefing, it was a little bit fuzzy,” Hobart veteran John Quinn says.

He had been speaking to me earlier this year but recalling events almost three decades ago, back in 1993.

“It could have been tough; they were a bit uncertain.”

He had been speaking to me earlier this year but recalling events almost three decades ago, back in 1993.

“It could have been tough; they were a bit uncertain.”

The crew’s biggest concern the morning of the start was the new mainsail.

“We were tossing up whether to use it or not, and we came to the decision to use it.

As it turned out, the [southerly change and accompanying low-pressure system] was a lot worse than what we thought it was going to be.”

“We were tossing up whether to use it or not, and we came to the decision to use it.

As it turned out, the [southerly change and accompanying low-pressure system] was a lot worse than what we thought it was going to be.”

With winds reaching over 70 knots, it was equivalent to a low‑grade hurricane, and Quinn and the crew aboard his J/35, MEM, hit the full force of the storm in the Bass Strait on Monday night, December 27, 1993.

Before midnight, a wave came out of nowhere.

“It came from an odd direction. It was a big wave. Picked us up, threw us straight over on her side. We had three down below, fortunately. All of us on deck, I think bar one, went over the side. I got washed straight out of the cockpit. And when my weight hit the harness, it busted. It was a harness inside the jacket that had been well cared for; it must’ve split the webbing or whatever happened. But anyway, I ended up in the water,” Quinn says.

The crew hit the man-overboard button and recorded the yacht’s position, which was transmitted with the mayday call, and the search started.

The water temperature was about 18 degrees C.

The predicted time to exhaustion and unconsciousness is between two and seven hours at that temperature, with the outside survival time at 40 hours.

It was the only thing he had going for him.

“We’re talking about seas of on average 8 meters, and they’re breaking,” Quinn says.

“So, the chances of seeing one individual off a yacht in that sort of condition in the middle of the night—and it was in the middle of the night—are sweet f— all.”

It was around 5 a.m.

on Tuesday morning when the oil tanker Ampol Sarel arrived at the search zone.

The captain, Bernie Holmes, started at the original point where Quinn had gone overboard, then shut down the engines and let the ship drift downwind.

He turned on all the lights so she would coast silently through the search area lit up like a Christmas tree.

Brent Shaw, a seaman aboard the tanker, heard Quinn’s cries.

“I was on the wing of the bridge, portside lookout, wearing my raincoat and rain hat when I thought I heard a scream,” he told reporters.

“With all the wind and rain, I wasn’t sure, so I took off my hat, and then I positively heard the scream.

I directed my searchlight toward the area—and there he was, waving and screaming.”

Quinn was about 20 meters away from the 100,000-ton tanker.

“The scary part was we spotted him, and then he drifted out of the searchlight, and then he was in the dark again,” Shaw said.

The Ampol Sarel crew radioed to other search boats that they had seen Quinn, and one that heard the message was the 40-footer Atara.

Its crew had already had their own share of adventure that night.

One of the crew was 21-year-old Tom Braidwood, who would go on to a career with America’s Cup and Volvo Ocean Race teams.

“It got to that stage where you couldn’t see the waves in the troughs. The white foam was filling all the troughs up. And the only way we knew—you’d hear the wave coming like a train and you’d be like, ‘Here we go.’”

Eventually, one of those waves had rumbled in and hit the sails of Atara with such force that it snapped the rig.

They cut it away, but not before it smashed a hole in the hull.

Atara was now in serious trouble.

They started pulling the bunks off the side of the boat and using them to try to shore up the structure because it was caving in under the wave motion.

It was at this moment that they heard about Quinn and diverted to the search area—even as they struggled to keep their own boat afloat.

“We got to the area, and we’re all on deck with torches down each side of the boat.

And we’re motoring around and next thing you know, we saw him and it was like… Talk about the luckiest guy on Earth. Well, unlucky falling in, but…”

They struggled to get him out of the water, lost him once, and had to do a couple of passes to get back to him.

“He was drifting on and off the boat, and it’s hard to keep him there,” Braidwood says.

“I had a harness on, so I turned around to the guys and said, ‘I’m going to go get him.’ I had my harness tied to a rope as well. I dove in and swam out to him. And as soon as I got him, it was like, uuuuhhhh, you know, like complete collapse.”

Braidwood got him back to the boat, and after an immense struggle, they got him on board.

“We dragged him down below, and he was hypothermic because all he had on was thermals and a dinghy vest, like a little life jacket, a bit padded.

That’s the thing that saved his life, you know, because he didn’t have a jacket, a wet-weather jacket, or anything.”

I first heard this story in Sydney, not long after that Hobart, which I had raced aboard Syd Fischer’s 50-foot Ragamuffin.

It took me nearly 30 years to get around to tracking down Quinn and asking him what he was doing in the water in hurricane conditions with no life jacket on.

The flotation vest Quinn was wearing enabled him to handle the breaking waves—so long as he was strong enough to keep himself afloat with its limited support.

Quinn was no naive newbie to sailing, neither the Hobart nor the risks.

He was brought up in Sydney and spent his childhood in and around the water.

“I did my first Hobart race at the age of 21, so I started ocean racing probably about the age of 18,” he told me.

By the time he was in his late 20s, he was part owner of a 33-footer, his first ocean racing boat, and over the next two decades he upgraded a couple of times, did a lot more Hobarts, and then bought MEM.

“I had on a Musto flotation vest. They were more for warmth, but they gave you a little bit of flotation.

I also had on a normal jacket, but it was weighing me down, so I got rid of it. And I had sea boots on, which I got rid of.”

But what about the life jacket?

Before midnight, a wave came out of nowhere.

“It came from an odd direction. It was a big wave. Picked us up, threw us straight over on her side. We had three down below, fortunately. All of us on deck, I think bar one, went over the side. I got washed straight out of the cockpit. And when my weight hit the harness, it busted. It was a harness inside the jacket that had been well cared for; it must’ve split the webbing or whatever happened. But anyway, I ended up in the water,” Quinn says.

The crew hit the man-overboard button and recorded the yacht’s position, which was transmitted with the mayday call, and the search started.

The water temperature was about 18 degrees C.

The predicted time to exhaustion and unconsciousness is between two and seven hours at that temperature, with the outside survival time at 40 hours.

It was the only thing he had going for him.

“We’re talking about seas of on average 8 meters, and they’re breaking,” Quinn says.

“So, the chances of seeing one individual off a yacht in that sort of condition in the middle of the night—and it was in the middle of the night—are sweet f— all.”

It was around 5 a.m.

on Tuesday morning when the oil tanker Ampol Sarel arrived at the search zone.

The captain, Bernie Holmes, started at the original point where Quinn had gone overboard, then shut down the engines and let the ship drift downwind.

He turned on all the lights so she would coast silently through the search area lit up like a Christmas tree.

Brent Shaw, a seaman aboard the tanker, heard Quinn’s cries.

“I was on the wing of the bridge, portside lookout, wearing my raincoat and rain hat when I thought I heard a scream,” he told reporters.

“With all the wind and rain, I wasn’t sure, so I took off my hat, and then I positively heard the scream.

I directed my searchlight toward the area—and there he was, waving and screaming.”

Quinn was about 20 meters away from the 100,000-ton tanker.

“The scary part was we spotted him, and then he drifted out of the searchlight, and then he was in the dark again,” Shaw said.

The Ampol Sarel crew radioed to other search boats that they had seen Quinn, and one that heard the message was the 40-footer Atara.

Its crew had already had their own share of adventure that night.

One of the crew was 21-year-old Tom Braidwood, who would go on to a career with America’s Cup and Volvo Ocean Race teams.

“It got to that stage where you couldn’t see the waves in the troughs. The white foam was filling all the troughs up. And the only way we knew—you’d hear the wave coming like a train and you’d be like, ‘Here we go.’”

Eventually, one of those waves had rumbled in and hit the sails of Atara with such force that it snapped the rig.

They cut it away, but not before it smashed a hole in the hull.

Atara was now in serious trouble.

They started pulling the bunks off the side of the boat and using them to try to shore up the structure because it was caving in under the wave motion.

It was at this moment that they heard about Quinn and diverted to the search area—even as they struggled to keep their own boat afloat.

“We got to the area, and we’re all on deck with torches down each side of the boat.

And we’re motoring around and next thing you know, we saw him and it was like… Talk about the luckiest guy on Earth. Well, unlucky falling in, but…”

They struggled to get him out of the water, lost him once, and had to do a couple of passes to get back to him.

“He was drifting on and off the boat, and it’s hard to keep him there,” Braidwood says.

“I had a harness on, so I turned around to the guys and said, ‘I’m going to go get him.’ I had my harness tied to a rope as well. I dove in and swam out to him. And as soon as I got him, it was like, uuuuhhhh, you know, like complete collapse.”

Braidwood got him back to the boat, and after an immense struggle, they got him on board.

“We dragged him down below, and he was hypothermic because all he had on was thermals and a dinghy vest, like a little life jacket, a bit padded.

That’s the thing that saved his life, you know, because he didn’t have a jacket, a wet-weather jacket, or anything.”

I first heard this story in Sydney, not long after that Hobart, which I had raced aboard Syd Fischer’s 50-foot Ragamuffin.

It took me nearly 30 years to get around to tracking down Quinn and asking him what he was doing in the water in hurricane conditions with no life jacket on.

The flotation vest Quinn was wearing enabled him to handle the breaking waves—so long as he was strong enough to keep himself afloat with its limited support.

Quinn was no naive newbie to sailing, neither the Hobart nor the risks.

He was brought up in Sydney and spent his childhood in and around the water.

“I did my first Hobart race at the age of 21, so I started ocean racing probably about the age of 18,” he told me.

By the time he was in his late 20s, he was part owner of a 33-footer, his first ocean racing boat, and over the next two decades he upgraded a couple of times, did a lot more Hobarts, and then bought MEM.

“I had on a Musto flotation vest. They were more for warmth, but they gave you a little bit of flotation.

I also had on a normal jacket, but it was weighing me down, so I got rid of it. And I had sea boots on, which I got rid of.”

But what about the life jacket?

“We had normal life jackets. You remember how bulky those things were. You can’t get around the boat on them. They’re terrible things.”

The life jackets on board MEM were of the type that relies on closed-cell polyethylene foam for buoyancy.

They were big and could be awkward to wear, and made it difficult to move around the boat.

So, Quinn decided not to wear it—despite the fact that if ever there was a time to be wearing a life jacket, this was it.

“We were relying on our safety harnesses really. You don’t expect to end up in the water if you’re using a safety harness, not when you’re clipped on,” he says.

He chose the harness as his personal safety gear, and now the harness had failed him.

He tried a couple of survival techniques he had picked up, including sealing the foul-weather jacket and filling it with air to provide buoyancy.

“There’s no way that that will work in real life,” he says.

He also tried pulling into a fetal position to protect himself as the waves hit him.

“That was one of the worst ideas they ever came up with because you get one of these waves that picks you up and it chucks you around—you get a roller coming up, and it just picks you up and it just throws you. I mean, it’ll throw a 4-ton yacht. I tried that first, decided that was a really bad idea.”

The problem was the breaking waves, the dangerous part being the white water.

“What I ended up doing was […] what we always used to do when the waves came at us when we were surfing: I just dived under it. The flotation vest wasn’t so buoyant that it stopped me [from] doing that, so I was able to get through them. I was looking around for lights all the time, of course. Doing a fair bit of praying, remembering all the fine things at home, and wondering what the hell I’m doing there, that sort of stuff.”

This technique would have been impossible in one of the life jackets aboard MEM.

“[They’re] very buoyant—I would’ve hated to have been out there with one of those things on,” he says.

The flotation vest Quinn was wearing enabled him to handle the breaking waves—so long as he was strong enough to keep himself afloat with its limited support.

“I was getting toward the end of it. I’d been through the shakes. I started to shiver and shake pretty badly, and the shakes were just going, and then all of a sudden, I saw all these lights, and I swam toward the lights. As it turned out, it was a great big oil tanker, and she was coming down at me. And I yelled, and then I realized this thing’s going to run over the top of me, so I ended up swimming away.”

There was another bad moment when the Ampol Sarel’s searchlight lost him.

“No sooner had the light gone off me and I remember going, ‘Oh, s—,’ and looking around, and then I saw the port and starboard lights of Atara.”

It was 5:09 a.m. when Quinn was pulled out of the water, five hours and 27 minutes after he went overboard.

“How could anyone do that?” Braidwood asks, reflecting on Quinn’s feat of endurance.

Exhausted and hypothermic, the crew of Atara got him into a bunk with one of the only crew who was still dry.

“We had the space blankets around him, jamming cups of tea into him,” as they resumed the passage home, Braidwood says.

They were ready for this—they had the equipment and knew what to do.

Quinn was lucky—lucky the flotation vest had allowed him to handle the waves, lucky to be found before he ran out of the strength needed to help its limited buoyancy keep him afloat, and lucky to be found by a well-crewed and prepared boat.

But again, only just… “Atara was in a total mess,” Quinn says.

“I don’t know what they were doing there. The mast had come down. She was totally delaminated. I mean, she was a total wreck.”

Braidwood was just as aware of the frailty of their position.

“I remember he came to, and he just turns around and he goes, ‘Oh, thanks guys.

Thanks fellas.’ You know, and I turned around and I said, ‘Well, don’t thank us yet mate because your ambulance is about to sink.’”

The indomitable streak that had got Quinn to that point came out in his reply.

“When they told me that the ambulance wasn’t in too good a shape, I think I said something rude.

Like, ‘Can I wait for the next one?’

“The first thing I did when I came back was I threw out all the life jackets,” he says.

“And I put inflatable life jackets on board the boat for everybody.

Because inflatable life jackets allow you to control your buoyancy in the same way as a diver can control their buoyancy.

And that I regard as absolutely critical because I think with a full life jacket [and] those waves picking you up, I don’t think you’d last very long.

“I made a number of fundamental mistakes,” he continues.

“The first thing is that I shouldn’t have been racing a boat that night in the Sydney to Hobart Race.

[It’s] a beautiful little coastal racing boat, the J/35, magnificent little boat, but [it’s] not designed to go into that sort of weather.

The second mistake I made was when I realized we were going into that sort of weather, I should have pulled the plug and just simply peacefully sailed into Twofold Bay.

Shouldn’t have allowed myself to get out of control, I know better than that.

They were the two fundamental mistakes.”

These mistakes all had a theme.

We could call it overconfidence—a deep belief that things were going to be all right, that nothing really bad was going to happen.

It allows us to do things that, in hindsight, particularly after our luck has run out, seem reckless.

At one point in the worst of the weather during that Hobart, I had unclipped my harness on the weather rail and slid down across the aft deck to get to the leeward runner.

My luck held and I got away with it, but not everyone does.

There is an innate bias to overconfidence in all of us, and it’s so hard to overcome because it’s instinctive—we don’t stop to think things through properly.

It would only have taken a moment’s pause to realize how foolish it was to be sliding around the open aft deck of a 50-footer without being clipped.

I did not pause.

I just acted because I had this inner innate confidence that it would be all right.

This instinctive overconfidence is a cognitive bias.

These biases (and there are many of them) are hard-wired predispositions to types of behavior.

The head of the TED organization, Chris Anderson, interviewed Daniel Kahneman (the Nobel Prize winner who, along with Amos Tversky, was responsible for the original work on cognitive bias) and asked if Kahneman could inject one idea into the minds of millions of people, what would that idea be? Kahneman replied, “Overconfidence is really the enemy of good thinking, and I wish that humility about our beliefs could spread.”

There is an innate bias to overconfidence in all of us, and it’s so hard to overcome because it’s instinctive—we don’t stop to think things through properly.

In the conclusion to his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman says: “Except for some effects that I attribute mostly to age, my intuitive thinking is just as prone to overconfidence, extreme predictions and the planning fallacy as it was before I made a study of these issues.

I have improved only in my ability to recognize situations in which errors are likely.

And I have made much more progress in recognizing the error of others than my own.”

Despite Daniel Kahneman’s pessimism—and speaking as someone who has made some bad choices—I’m going to keep trying to do better.

It’s surprising how often we can mitigate risks with little more than a moment’s thought.

It can be as simple as putting a strobe light in the pocket of your foul-weather gear.

Or as simple as throwing a shovel and a couple of blankets in the back of the car at the start of the winter.

There are a few strategies we can employ to help us overcome the pernicious bias of overconfidence, ways to learn to slow down and pay better attention.

One of them is to build habits to review risk whenever there’s time to do so.

I sailed in the 1993 Hobart Race with Neal McDonald, who went on to sail with six Volvo Ocean Race teams, twice as skipper, leading Assa Abloy to a second-place finish.

He developed the habit of playing a “what if” game during any pause in the action.

At any moment, he could start a pop quiz: “What do we do if that sail breaks?” or “What’s the repair if the steering gear fails?”

McDonald was constantly looking for solutions to problems he did not yet have, and it’s a powerful tool in raising everyone’s awareness of risk.

A more formal mechanism that does much the same job is the pre-mortem, an idea that came from research psychologist Gary Klein.

The principle is straightforward: Before any major decision goes forward, all the people involved in it gather for a pre-mortem in which they project forward a year after the decision was enacted.

The basis for the meeting is that the decision was a disaster, and everyone must explain why.

Klein thinks that it works because it frees people to speak up about the weaknesses of a project or plan.

While McDonald’s “what if” game and the pre-mortem are good at revealing what might otherwise be hidden risks—like the bulky life jackets—there is another strategy that can force a rethink on what’s an acceptable risk and what’s not.

This one was prevalent within the OneWorld America’s Cup team in the early 2000s, where almost any assertion could be met with the riposte, “You wanna put some money on that?”

The life jackets on board MEM were of the type that relies on closed-cell polyethylene foam for buoyancy.

They were big and could be awkward to wear, and made it difficult to move around the boat.

So, Quinn decided not to wear it—despite the fact that if ever there was a time to be wearing a life jacket, this was it.

“We were relying on our safety harnesses really. You don’t expect to end up in the water if you’re using a safety harness, not when you’re clipped on,” he says.

He chose the harness as his personal safety gear, and now the harness had failed him.

He tried a couple of survival techniques he had picked up, including sealing the foul-weather jacket and filling it with air to provide buoyancy.

“There’s no way that that will work in real life,” he says.

He also tried pulling into a fetal position to protect himself as the waves hit him.

“That was one of the worst ideas they ever came up with because you get one of these waves that picks you up and it chucks you around—you get a roller coming up, and it just picks you up and it just throws you. I mean, it’ll throw a 4-ton yacht. I tried that first, decided that was a really bad idea.”

The problem was the breaking waves, the dangerous part being the white water.

“What I ended up doing was […] what we always used to do when the waves came at us when we were surfing: I just dived under it. The flotation vest wasn’t so buoyant that it stopped me [from] doing that, so I was able to get through them. I was looking around for lights all the time, of course. Doing a fair bit of praying, remembering all the fine things at home, and wondering what the hell I’m doing there, that sort of stuff.”

This technique would have been impossible in one of the life jackets aboard MEM.

“[They’re] very buoyant—I would’ve hated to have been out there with one of those things on,” he says.

The flotation vest Quinn was wearing enabled him to handle the breaking waves—so long as he was strong enough to keep himself afloat with its limited support.

“I was getting toward the end of it. I’d been through the shakes. I started to shiver and shake pretty badly, and the shakes were just going, and then all of a sudden, I saw all these lights, and I swam toward the lights. As it turned out, it was a great big oil tanker, and she was coming down at me. And I yelled, and then I realized this thing’s going to run over the top of me, so I ended up swimming away.”

There was another bad moment when the Ampol Sarel’s searchlight lost him.

“No sooner had the light gone off me and I remember going, ‘Oh, s—,’ and looking around, and then I saw the port and starboard lights of Atara.”

It was 5:09 a.m. when Quinn was pulled out of the water, five hours and 27 minutes after he went overboard.

“How could anyone do that?” Braidwood asks, reflecting on Quinn’s feat of endurance.

Exhausted and hypothermic, the crew of Atara got him into a bunk with one of the only crew who was still dry.

“We had the space blankets around him, jamming cups of tea into him,” as they resumed the passage home, Braidwood says.

They were ready for this—they had the equipment and knew what to do.

Quinn was lucky—lucky the flotation vest had allowed him to handle the waves, lucky to be found before he ran out of the strength needed to help its limited buoyancy keep him afloat, and lucky to be found by a well-crewed and prepared boat.

But again, only just… “Atara was in a total mess,” Quinn says.

“I don’t know what they were doing there. The mast had come down. She was totally delaminated. I mean, she was a total wreck.”

Braidwood was just as aware of the frailty of their position.

“I remember he came to, and he just turns around and he goes, ‘Oh, thanks guys.

Thanks fellas.’ You know, and I turned around and I said, ‘Well, don’t thank us yet mate because your ambulance is about to sink.’”

The indomitable streak that had got Quinn to that point came out in his reply.

“When they told me that the ambulance wasn’t in too good a shape, I think I said something rude.

Like, ‘Can I wait for the next one?’

“The first thing I did when I came back was I threw out all the life jackets,” he says.

“And I put inflatable life jackets on board the boat for everybody.

Because inflatable life jackets allow you to control your buoyancy in the same way as a diver can control their buoyancy.

And that I regard as absolutely critical because I think with a full life jacket [and] those waves picking you up, I don’t think you’d last very long.

“I made a number of fundamental mistakes,” he continues.

“The first thing is that I shouldn’t have been racing a boat that night in the Sydney to Hobart Race.

[It’s] a beautiful little coastal racing boat, the J/35, magnificent little boat, but [it’s] not designed to go into that sort of weather.

The second mistake I made was when I realized we were going into that sort of weather, I should have pulled the plug and just simply peacefully sailed into Twofold Bay.

Shouldn’t have allowed myself to get out of control, I know better than that.

They were the two fundamental mistakes.”

These mistakes all had a theme.

We could call it overconfidence—a deep belief that things were going to be all right, that nothing really bad was going to happen.

It allows us to do things that, in hindsight, particularly after our luck has run out, seem reckless.

At one point in the worst of the weather during that Hobart, I had unclipped my harness on the weather rail and slid down across the aft deck to get to the leeward runner.

My luck held and I got away with it, but not everyone does.

There is an innate bias to overconfidence in all of us, and it’s so hard to overcome because it’s instinctive—we don’t stop to think things through properly.

It would only have taken a moment’s pause to realize how foolish it was to be sliding around the open aft deck of a 50-footer without being clipped.

I did not pause.

I just acted because I had this inner innate confidence that it would be all right.

This instinctive overconfidence is a cognitive bias.

These biases (and there are many of them) are hard-wired predispositions to types of behavior.

The head of the TED organization, Chris Anderson, interviewed Daniel Kahneman (the Nobel Prize winner who, along with Amos Tversky, was responsible for the original work on cognitive bias) and asked if Kahneman could inject one idea into the minds of millions of people, what would that idea be? Kahneman replied, “Overconfidence is really the enemy of good thinking, and I wish that humility about our beliefs could spread.”

There is an innate bias to overconfidence in all of us, and it’s so hard to overcome because it’s instinctive—we don’t stop to think things through properly.

In the conclusion to his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman says: “Except for some effects that I attribute mostly to age, my intuitive thinking is just as prone to overconfidence, extreme predictions and the planning fallacy as it was before I made a study of these issues.

I have improved only in my ability to recognize situations in which errors are likely.

And I have made much more progress in recognizing the error of others than my own.”

Despite Daniel Kahneman’s pessimism—and speaking as someone who has made some bad choices—I’m going to keep trying to do better.

It’s surprising how often we can mitigate risks with little more than a moment’s thought.

It can be as simple as putting a strobe light in the pocket of your foul-weather gear.

Or as simple as throwing a shovel and a couple of blankets in the back of the car at the start of the winter.

There are a few strategies we can employ to help us overcome the pernicious bias of overconfidence, ways to learn to slow down and pay better attention.

One of them is to build habits to review risk whenever there’s time to do so.

I sailed in the 1993 Hobart Race with Neal McDonald, who went on to sail with six Volvo Ocean Race teams, twice as skipper, leading Assa Abloy to a second-place finish.

He developed the habit of playing a “what if” game during any pause in the action.

At any moment, he could start a pop quiz: “What do we do if that sail breaks?” or “What’s the repair if the steering gear fails?”

McDonald was constantly looking for solutions to problems he did not yet have, and it’s a powerful tool in raising everyone’s awareness of risk.

A more formal mechanism that does much the same job is the pre-mortem, an idea that came from research psychologist Gary Klein.

The principle is straightforward: Before any major decision goes forward, all the people involved in it gather for a pre-mortem in which they project forward a year after the decision was enacted.

The basis for the meeting is that the decision was a disaster, and everyone must explain why.

Klein thinks that it works because it frees people to speak up about the weaknesses of a project or plan.

While McDonald’s “what if” game and the pre-mortem are good at revealing what might otherwise be hidden risks—like the bulky life jackets—there is another strategy that can force a rethink on what’s an acceptable risk and what’s not.

This one was prevalent within the OneWorld America’s Cup team in the early 2000s, where almost any assertion could be met with the riposte, “You wanna put some money on that?”

And I can tell you, the prospect of losing cold, hard cash forces one to reconsider any misguided optimism very quickly.

Annie Duke, a former professional poker player, goes into this strategy in some detail in her book Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts.

Along with Don Moore’s Perfectly Confident: How to Calibrate Your Decisions Wisely, it’s an excellent book to help understand our disposition for risk-taking—no bad thing when you consider the consequences of hauling up an anchor or untying the dock lines.

For all its wonder and immense beauty, the sea is fundamentally hostile to human life; without the support of a ship or boat, our survival has a limited time horizon.

If you’re not convinced, just ask John Quinn.

Annie Duke, a former professional poker player, goes into this strategy in some detail in her book Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts.

Along with Don Moore’s Perfectly Confident: How to Calibrate Your Decisions Wisely, it’s an excellent book to help understand our disposition for risk-taking—no bad thing when you consider the consequences of hauling up an anchor or untying the dock lines.

For all its wonder and immense beauty, the sea is fundamentally hostile to human life; without the support of a ship or boat, our survival has a limited time horizon.

If you’re not convinced, just ask John Quinn.

Links :

- Sailing World : Crew Overboard: Four Recovery Methods

- The lucky yachtsman

- GeoGarage blog : Drowning doesn't look like drownin / The cold shocking truth…. about cold water shock

No comments:

Post a Comment