The pipeline that leaked oil into the ocean off Orange County in early October 2021 may have been damaged in more than one incident, and as early as months ago, U.S. Coast Guard investigators said. (Photo from video taken by Petty Officer 1st Class Richard Brahm, U.S. Coast Guard)

From The OCR by Brooke Staggs

With a ship anchor suspected in the oil spill off Huntington Beach, and with record volumes of traffic in San Pedro Bay, some local leaders demand a new offshore survey.

More than four decades ago, Shell Oil Company submitted blueprints for a 17-mile-long pipeline to connect its oil processing platform off the coast of Huntington Beach with a pumping station at the Port of Long Beach.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration took Shell’s drawings and used them to add the pipeline to the nautical charts all vessels still use when navigating coastal waters.

The last time NOAA surveyed the waters off the coast of Southern California — to verify that the now 41-year-old pipeline and other possible hazards, including ocean depths, is accurate on nautical charts — was in 2013.

The last time NOAA surveyed the waters off the coast of Southern California — to verify that the now 41-year-old pipeline and other possible hazards, including ocean depths, is accurate on nautical charts — was in 2013.

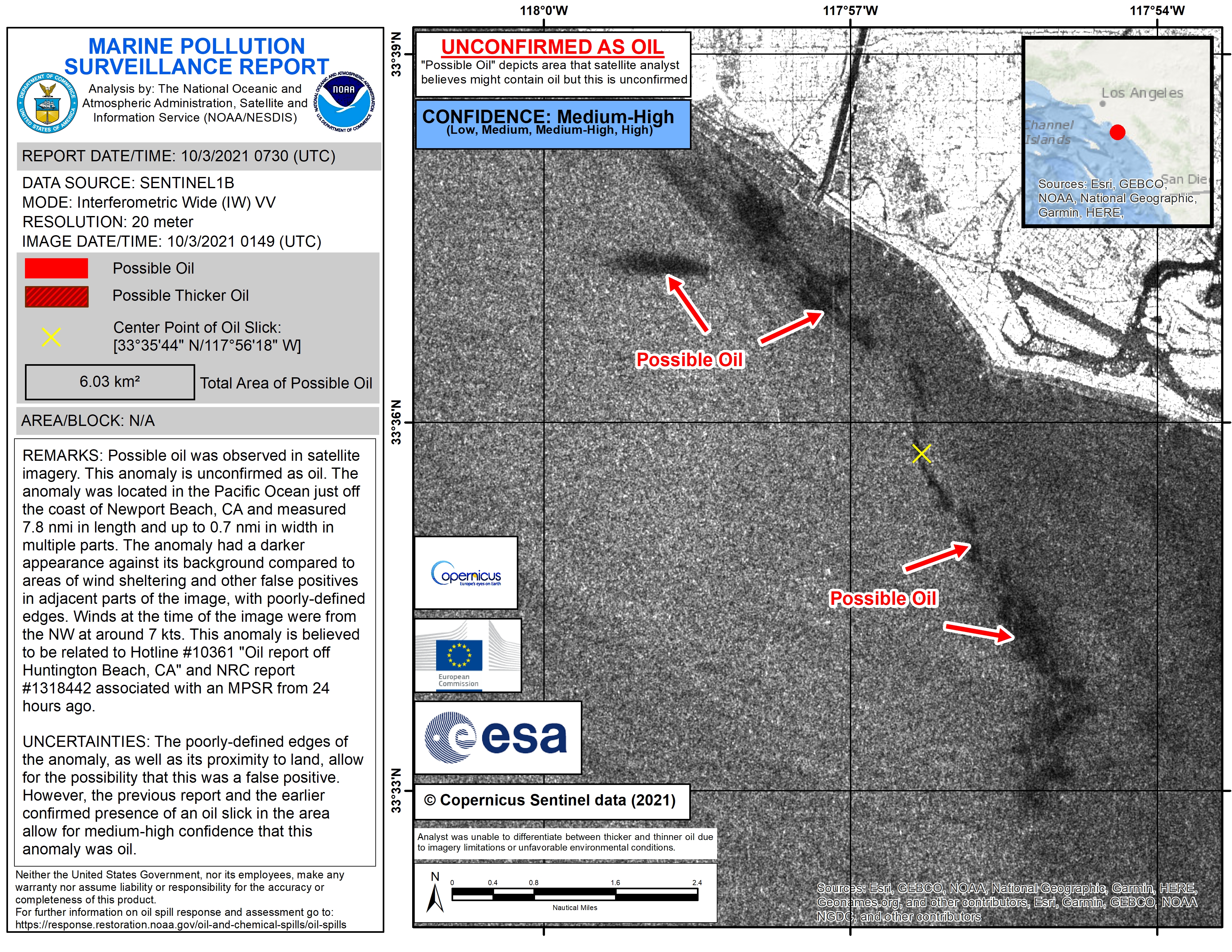

NASA/NOAA Marine Pollution Response Report, Sentinel 1B Imagery (October 3, 2021)

Since then, per NOAA, no surveys have been ordered and no changes have been made to the local nautical charts.

But initial U.S. Coast Guard investigations suggest that in January a ship’s anchor dragged Shell’s pipeline, now operated by a subsidiary of Amplify Energy, more than 100 feet, meaning that pipeline’s location isn’t listed accurately on any existing chart.

That event might have triggered damage that eventually caused the pipeline to rupture and spill an estimated 25,000 gallons into the ocean in early October.

There also are a record number of ships anchoring and loitering in the San Pedro Bay this year due to gridlock at the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles.

There also are a record number of ships anchoring and loitering in the San Pedro Bay this year due to gridlock at the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles.

Those ships can’t all fit at approved anchorage spots.

They also move massive volumes of water as they come in and out of the bay — a phenomenon that according to James Fawcett, an environmental studies professor at USC who specializes in maritime policy, can shift enough sediment to change ocean depths.

That’s why Rep. Michelle Steel, R-Seal Beach, whose 48th District includes beaches most affected by the October oil spill, sent a letter Oct. 14 calling for NOAA and the Coast Guard to immediately survey waters off the coast of Orange County and make any necessary updates to nautical charts.

That’s why Rep. Michelle Steel, R-Seal Beach, whose 48th District includes beaches most affected by the October oil spill, sent a letter Oct. 14 calling for NOAA and the Coast Guard to immediately survey waters off the coast of Orange County and make any necessary updates to nautical charts.

A bipartisan group of 10 state, county and local leaders, plus three coastal cities, signed on in support of Steel’s letter, which also asked for additional resources to address the effects of the oil spill.

“Any moment wasted is a moment too long if existing pipelines are mapped improperly or moved,” Steel said during an Oct. 22 hearing of the House Transportation and Infrastructure committee.

As of Friday, Steel’s office said they hadn’t yet received any response from NOAA or the Coast Guard.

“Any moment wasted is a moment too long if existing pipelines are mapped improperly or moved,” Steel said during an Oct. 22 hearing of the House Transportation and Infrastructure committee.

As of Friday, Steel’s office said they hadn’t yet received any response from NOAA or the Coast Guard.

While the investigation into the cause of the spill continues, the incident has sparked debate about whether offshore waters should be surveyed more often, whether federal authorities are overly reliant on oil companies to self-report potential problems, and if larger buffers between pipelines and anchor spots are needed.

How do offshore pipelines, including the one that leaked off Huntington Beach last month, end up on nautical charts?

NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey uses final construction drawings from pipeline owners to add pipeline locations to navigation charts, according to the agency. NOAA regularly reviews permit requests submitted to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement for new and modified pipelines, then updates charts based on drawings submitted by the pipeline owner.

During the Oct. 22 Transportation and Infrastructure hearing, Vice Admiral Scott Buschman with the U.S. Coast Guard said they confirmed that the pipeline that leaked in early October was included on nautical charts.

No pipeline location on NOAA ENC

Relying on oil companies to supply pipeline locations for nautical charts doesn’t worry Fawcett.

The process of installing pipelines is intricate, and requires the company to work with multiple federal agencies, the USC professor noted.

The process of installing pipelines is intricate, and requires the company to work with multiple federal agencies, the USC professor noted.

Plus, he said, pipelines are only allowed in areas believed to be safe from marine traffic and other hazards.

Pipeline owners don’t want to put them outside of safe zones because of the risk of potentially expensive damage.

Does anyone verify the location of those pipelines and check on them over time?

NOAA generally checks pipeline locations only when they lie within an area otherwise approved for a hydrographic survey, the agency said.

There is no set schedule for NOAA to conduct new surveys.

Does anyone verify the location of those pipelines and check on them over time?

NOAA generally checks pipeline locations only when they lie within an area otherwise approved for a hydrographic survey, the agency said.

There is no set schedule for NOAA to conduct new surveys.

The agency’s Office of Coast Survey generally conducts them in response to requests when there’s heightened concern about risks due to issues such as dense traffic or reported ship groundings.

And they prioritize requests based on a variety of conditions, such as proximity to marine sanctuaries and what models show about likelihood of changes on the sea floor.

Everyone seems to agree that more frequent surveys would be helpful.

Everyone seems to agree that more frequent surveys would be helpful.

But the process is pricey, and so, under the Hydrographic Services Improvement Act of 1998, NOAA is required to get such data from the private sector “to the greatest extent practicable and cost-effective.”

Earlier this year — prior to the spill off Orange County — the agency announced a matching funds program to encourage private entities to help expand coastal survey efforts.

The last time NOAA surveyed the San Pedro Bay was in 2013 after the agency said it received requests “from the Port of Los Angeles, the Port of Long Beach and the pilots who maneuver increasing large oil tankers and cargo ships through the area’s crowded shipping lanes.”

The last time NOAA surveyed the San Pedro Bay was in 2013 after the agency said it received requests “from the Port of Los Angeles, the Port of Long Beach and the pilots who maneuver increasing large oil tankers and cargo ships through the area’s crowded shipping lanes.”

Before that, a survey was conducted in 2010.

In 2013, the agency said NOAA Ship Fairweather confirmed the San Pedro Bay pipeline was charted in the location that matched the chart.

In 2013, the agency said NOAA Ship Fairweather confirmed the San Pedro Bay pipeline was charted in the location that matched the chart.

And NOAA said it recently reviewed charts off Orange County, comparing them with BSEE pipeline permits and hydrographic survey data from 2013, and said the pipelines have been accurately charted to current standards.

NOAA declined to say how much it would cost to conduct a new survey offshore Orange County, but estimated it would take 12 hours with three survey launches to complete.

But while NOAA surveys don’t happen often, Fawcett said pipelines and most other underwater hazards don’t typically move much, and anchor drags by large ships aren’t common.

NOAA declined to say how much it would cost to conduct a new survey offshore Orange County, but estimated it would take 12 hours with three survey launches to complete.

But while NOAA surveys don’t happen often, Fawcett said pipelines and most other underwater hazards don’t typically move much, and anchor drags by large ships aren’t common.

He noted there also are other ways that authorities might still learn about a pipeline moving from its charted location.

“Generally — especially in this area, where there is a lot of marine traffic — there is a lot of underwater surveillance for one reason or another,” Fawcett said. With this pipeline on the surface of the ocean floor, he said, “You can see it on sonar if anybody is looking for it.”

Inspection is a separate issue.

“Generally — especially in this area, where there is a lot of marine traffic — there is a lot of underwater surveillance for one reason or another,” Fawcett said. With this pipeline on the surface of the ocean floor, he said, “You can see it on sonar if anybody is looking for it.”

Inspection is a separate issue.

Oil companies are required to inspect their pipelines on dictated schedules. In the case of the local line that ruptured, pipeline owner Amplify has alternated internal and external inspections annually, each no more than 13 months apart.

The last external inspection of the line was conducted in October 2020, perhaps three months before a ship struck the pipe and a full year before the rupture that caused the spill.

What happens if a pipeline moves?

What happens if a pipeline moves?

How are maps updated?

If a pipeline is found to have moved from its original location during an NOAA survey, that new information is reported to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

If a pipeline is found to have moved from its original location during an NOAA survey, that new information is reported to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

And “if the change poses a threat to navigational safety, NOAA will update its nautical chart.”

If an oil company or anyone else detects a change in the pipeline at any point, NOAA said the information should be reported to them and they’ll update electronic navigational charts of the area accordingly.

“We have not received new information that would indicate that the pipelines have moved,” NOAA told the Register last week.

“If a new survey is soon required,” NOAA said, “this would likely be done by the pipeline owner.”

If an oil company or anyone else detects a change in the pipeline at any point, NOAA said the information should be reported to them and they’ll update electronic navigational charts of the area accordingly.

“We have not received new information that would indicate that the pipelines have moved,” NOAA told the Register last week.

“If a new survey is soon required,” NOAA said, “this would likely be done by the pipeline owner.”

The agency said it would then use that information provided by Amplify Energy to update its nautical charts.

But when asked about notifying NOAA of its moved pipeline, Amplify Energy spokesmen said the estimated 100 feet of movement is still well within a 200-foot-wide right-of-way federal authorities permitted in 1998, so they don’t believe the shift triggered reporting requirements.

The company, which already is the target of multiple lawsuits over the spill, also pointed out the responsibility ships face in these situations.

How do ships navigate around pipelines in coastal waters?

But when asked about notifying NOAA of its moved pipeline, Amplify Energy spokesmen said the estimated 100 feet of movement is still well within a 200-foot-wide right-of-way federal authorities permitted in 1998, so they don’t believe the shift triggered reporting requirements.

The company, which already is the target of multiple lawsuits over the spill, also pointed out the responsibility ships face in these situations.

How do ships navigate around pipelines in coastal waters?

And are larger buffers needed?

All large vessels, like those waiting to enter the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, are required to refer to electronic navigational charts maintained by NOAA that include pipeline locations.

When it comes to anchoring offshore, the Marine Exchange of Southern California assigns ships particular anchorage points that have long been designated as safe.

All large vessels, like those waiting to enter the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, are required to refer to electronic navigational charts maintained by NOAA that include pipeline locations.

When it comes to anchoring offshore, the Marine Exchange of Southern California assigns ships particular anchorage points that have long been designated as safe.

Ships are required to drop anchor — and, more importantly, volumes of heavy chain fixed to that anchor — in the dead center of these anchorage points, Fawcett explained.

The weight of the chain and anchor then allows the ship to drift only in a fixed circle and stay within the designated safety zone.

But with global supply chain issues this year creating delayed cargo traffic — and dozens of huge ships unable to get into local ports — some vessels have been directed to anchor in non-typical locations. That’s where accuracy of NOAA’s nautical maps becomes key, so everyone can be sure ships steer clear of pipelines and other hazards.

It’s not clear if there’s a specific fixed distance that’s required between oil pipelines and permitted anchorage points. Federal agencies didn’t respond to requests for that information.

Still, early investigations suggest it wasn’t a problem with nautical maps or anchor placement that might have triggered the October oil spill.

But with global supply chain issues this year creating delayed cargo traffic — and dozens of huge ships unable to get into local ports — some vessels have been directed to anchor in non-typical locations. That’s where accuracy of NOAA’s nautical maps becomes key, so everyone can be sure ships steer clear of pipelines and other hazards.

It’s not clear if there’s a specific fixed distance that’s required between oil pipelines and permitted anchorage points. Federal agencies didn’t respond to requests for that information.

Still, early investigations suggest it wasn’t a problem with nautical maps or anchor placement that might have triggered the October oil spill.

Instead, Coast Guard investigations suggest one or more ships dragged anchor during unusually strong winds in January, eventually moving a 4000-foot section of Amplify Energy’s pipeline out of place by 100 to 150 feet.

They believe that an anchor damaged a concrete casing around the pipe, which started leaking Oct. 1.

It’s not common for ships to drag anchor.

It’s not common for ships to drag anchor.

Fawcett said it generally only happens during strong winds. And ships are required to have a crew member on watch at all times and to quickly report incidents where they’ve dragged anchor and crossed into pipeline rights of way.

With those investigations ongoing, Fawcett said it’s tough to know whether larger buffers between anchor points and pipelines — or any other changes to maritime policy — could have prevented the spill.

“I suspect there will be recommendations once the reports come out,” he said.

With those investigations ongoing, Fawcett said it’s tough to know whether larger buffers between anchor points and pipelines — or any other changes to maritime policy — could have prevented the spill.

“I suspect there will be recommendations once the reports come out,” he said.

“But right now I think it’s premature.”

Links :

Links :

- CBS : Huntington Beach Oil Spill: Section Of Pipeline Found Damaged, Moved More Than 100 Feet Along Ocean Floor

- NOAA : Update on NOAA Support for California Oil Spill

- NPR : The California oil spill was about 25,000 gallons — one-fifth what officials feared

- CNN : In pictures: Oil spill in Southern California

- The Guardian : Why California’s enormous oil spill won’t be its last / California justice department to investigate enormous oil spill

- LA Times : Will those responsible for O.C. oil spill pay for the damage? It could be a battle

No comments:

Post a Comment