In June 1974, a large and bulky ship, the Hughes Glomar Explorer, exited Long Beach, California, sailing westward into the Pacific.

Boasting an enormous drilling tower, and owned by the notorious and reclusive billionaire, Howards Hughes, the vessel was reportedly intended to recover thousands of tons per week of copper, nickel, manganese and cobalt from the floor of the Pacific.

These resources, real enough, exist in potato-sized nodules on the deep sea bed, way beyond any nation’s home waters.

Even by Hughes’s standards, a project to mine the deep seabed was intriguing.

Manganese, a light metal used in a variety of industrial contexts, commands a certain price in world commodity markets — though many doubted whether this could justify the massive costs of building the Hughes Glomar Explorer,particularly given how deep the Pacific’s seabed can be.

Indeed, in the waters off California, the Pacific floor soon drops to depths of 3,000 to 4,000 meters (1.8 to 2.4 miles).

Even assuming such a vessel need not reach the deepest parts of the Pacific seabed floor (such as the Mariana Trench, which can be in excess of 10,000 meters, or 6 miles), the required effort, in terms of capital, labor and know-how, required to reach the manganese nodules would have been both enormous and unprecedented.

Boasting an enormous drilling tower, and owned by the notorious and reclusive billionaire, Howards Hughes, the vessel was reportedly intended to recover thousands of tons per week of copper, nickel, manganese and cobalt from the floor of the Pacific.

These resources, real enough, exist in potato-sized nodules on the deep sea bed, way beyond any nation’s home waters.

Even by Hughes’s standards, a project to mine the deep seabed was intriguing.

Manganese, a light metal used in a variety of industrial contexts, commands a certain price in world commodity markets — though many doubted whether this could justify the massive costs of building the Hughes Glomar Explorer,particularly given how deep the Pacific’s seabed can be.

Indeed, in the waters off California, the Pacific floor soon drops to depths of 3,000 to 4,000 meters (1.8 to 2.4 miles).

Even assuming such a vessel need not reach the deepest parts of the Pacific seabed floor (such as the Mariana Trench, which can be in excess of 10,000 meters, or 6 miles), the required effort, in terms of capital, labor and know-how, required to reach the manganese nodules would have been both enormous and unprecedented.

Aerial photograph of ships in Suisun Bay, California, mothballed for future defense use by the US Navy.

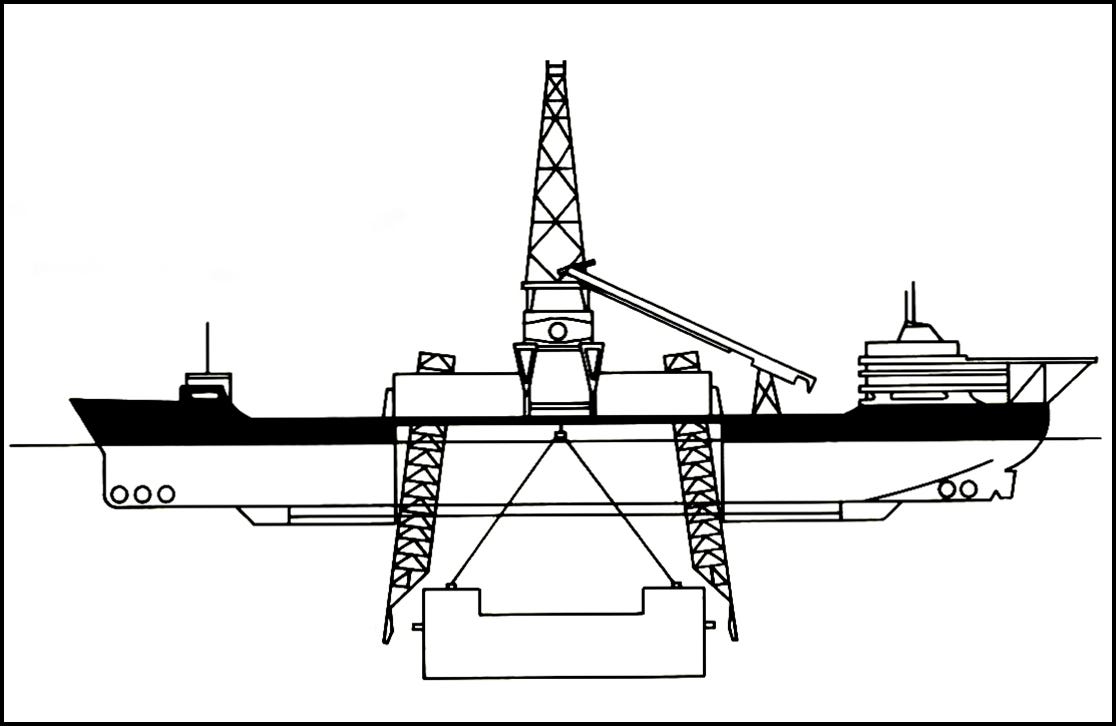

Aerial photograph of ships in Suisun Bay, California, mothballed for future defense use by the US Navy.At the bottom left is the Howard Hughes barge HMB-1 which was used with the Glomar Explorer, to transport defense-sensitive vessels in a manner protected from observation.

Wikimedia Commons

Legally too, the notion of mining the deep seabed (or “ocean floor”) was a novel topic.

Historically, the ocean floor was not the subject of significant commercial use, except for the laying of transoceanic submarine cables.

It was only charted in detail in the mid-1870s, by the British vessel HMS Challenger (in whose honor a space shuttle was later named).

Even with the laying of transoceanic cables — which began in the 1850s — this area did not receive much legal attention.

It was widely accepted that the deep seabed had essentially the same status as the high seas themselves — namely, that each state has the right to travel there, and no state can claim exclusive ownership over its resources.

It was thus recognized that the deep seabed was distinct –physically and legally — from the “continental shelf” (the area immediately alongside the coastal areas).

A 1958 convention provided that the continental shelf belonged to the appurtenant coastal state — but stopped short of regulating the deep seabed.

New technology changed the focus.

In 1960, in a project sponsored by the U.S. Navy, the bathyscaphe Trieste reached the ocean floor in part of the Mariana Trench, at a depth of 10,916 meters.

In the same decade, both the U.S. and Soviet navies fielded large submarine fleets, led by nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed boats on permanent rotation (albeit at far shallower depths than the Trieste).

Technology had by now confirmed that the seabed held potentially significant mineral deposits, as noted above.

Yet, legally, the seabed was still a “no man’s land.”

Things changed in 1967, when at the urging of the Maltese Ambassador to the United States, Arvid Pardo, the United Nations General Assembly established an ad hoc committee to study a legal regime that would ensure “that the exploration and use of the seabed and the ocean floor should be conducted in accordance with the principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations, in the interests of maintaining international peace and security and for the benefit of all mankind.”

Alongside these efforts, a separate U.N. committee became responsible for “seabed-related military and arms control issues.”

This had the enthusiastic support of the Nixon Administration.

On March 18, 1969, President Nixon supported efforts to ban deployment of nuclear weapons on the seabed, remarking that this would “prevent an arms race before it has a chance to start.”

This had the enthusiastic support of the Nixon Administration.

On March 18, 1969, President Nixon supported efforts to ban deployment of nuclear weapons on the seabed, remarking that this would “prevent an arms race before it has a chance to start.”

And on May 23, 1970, President Nixon proposed that “all nations adopted as soon as possible a treaty under which they would renounce all national claims over the natural resources of the seabed beyond the point where the high seas reach a depth of 200 meters (218.8 yards) and would agree to regard these resources as the common heritage of mankind.”

President Nixon further called for an international body to regulate mining of the deep seabed.

The first of these initiatives bore fruit almost immediately: in 1971, in recognition that “prevention of a nuclear arms race on the seabed and the ocean floor serves the interests of maintaining world peace,” the major powers signed the “Seabed Arms Control Treaty,” committing each party to refrain from placing on the seabed “any nuclear weapons or any other types of weapons of mass destruction as well as structures, launching installations or any other facilities specifically designed for storing, testing or using such weapons.”

The second Nixon proposal — a treaty to regulate the deep sea bed — had a promising start.

In 1970 the U.N. General Assembly had passed a resolution to establish a general “Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea” (“UNCLOS III”), to establish a new comprehensive treaty on the law of the sea.

UNCLOS III, which first met in 1973, became an ongoing convocation international lawyers and experts from 160 countries, whose mission was to formulate a “Law of the Sea Convention” (or “LOSC”).

For much of its nine years of activity, much of UNCLOS III’s work consisted of codifying existing rules (e.g., rights of navigation on the high seas and the rights of coastal states to exploit their adjacent continental shelf).

But on some issues, such as how and whether the deep seabed could be exploited — which formed “Part XI” of the draft Law of the Sea Convention, UNCLOS III’s delegates were grappling with new policy issues.

In early sessions of UNCLOS III, U.S. State Department negotiators favored a system that would give security of title, and a transparent regulatory system, for mining operators seeking to mine the deep seabed.

They sought to promptly conclude a treaty along those lines.

Meanwhile, some members of Congress, suspicious of this internationalist approach, sponsored unilateral legislation (a Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Act) that would explicitly permit mining under purely national regulations.

Despite bills being introduced between 1971 and 1975, none made it out of committee, apparently because of pressure from the Executive (which was negotiating at UNCLOS III).

Other countries’ negotiators had a quite different vision of how the deep seabed should be regulated, and in May 1974, a group of developing and landlocked states issued what become known as the “Kampala Declaration,” demanding that UNCLOS III take into account the needs of “landlocked and geographically disadvantaged States.”

The first of these initiatives bore fruit almost immediately: in 1971, in recognition that “prevention of a nuclear arms race on the seabed and the ocean floor serves the interests of maintaining world peace,” the major powers signed the “Seabed Arms Control Treaty,” committing each party to refrain from placing on the seabed “any nuclear weapons or any other types of weapons of mass destruction as well as structures, launching installations or any other facilities specifically designed for storing, testing or using such weapons.”

The second Nixon proposal — a treaty to regulate the deep sea bed — had a promising start.

In 1970 the U.N. General Assembly had passed a resolution to establish a general “Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea” (“UNCLOS III”), to establish a new comprehensive treaty on the law of the sea.

UNCLOS III, which first met in 1973, became an ongoing convocation international lawyers and experts from 160 countries, whose mission was to formulate a “Law of the Sea Convention” (or “LOSC”).

For much of its nine years of activity, much of UNCLOS III’s work consisted of codifying existing rules (e.g., rights of navigation on the high seas and the rights of coastal states to exploit their adjacent continental shelf).

But on some issues, such as how and whether the deep seabed could be exploited — which formed “Part XI” of the draft Law of the Sea Convention, UNCLOS III’s delegates were grappling with new policy issues.

In early sessions of UNCLOS III, U.S. State Department negotiators favored a system that would give security of title, and a transparent regulatory system, for mining operators seeking to mine the deep seabed.

They sought to promptly conclude a treaty along those lines.

Meanwhile, some members of Congress, suspicious of this internationalist approach, sponsored unilateral legislation (a Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Act) that would explicitly permit mining under purely national regulations.

Despite bills being introduced between 1971 and 1975, none made it out of committee, apparently because of pressure from the Executive (which was negotiating at UNCLOS III).

Other countries’ negotiators had a quite different vision of how the deep seabed should be regulated, and in May 1974, a group of developing and landlocked states issued what become known as the “Kampala Declaration,” demanding that UNCLOS III take into account the needs of “landlocked and geographically disadvantaged States.”

This agenda, which was taken up by the so-called “Group of 77” (a coalition of developing states), led their negotiators to urge for a strong central seabed authority with wide rule-making powers over seabed mining.

The developing states furthermore viewed the “common heritage of mankind” as meaning that deep seabed minerals were collectively owned by all countries.

In the words of one negotiator (a Sri Lankan diplomat), “[i]f you touch the nodules at the bottom of the sea, you touch my property.

If you take them away, you take away my property.”

The developing states furthermore viewed the “common heritage of mankind” as meaning that deep seabed minerals were collectively owned by all countries.

In the words of one negotiator (a Sri Lankan diplomat), “[i]f you touch the nodules at the bottom of the sea, you touch my property.

If you take them away, you take away my property.”

UNCLOS Maritime Zones

Things came to head in July 1977, with the release of the UNCLOS III “Informal Composite Negotiating Text” for the LOSC.

This text included a “Part XI” to regulate the deep seabed.

Under this text, the deep seabed (defined as “the Area”) was declared to the “common heritage of mankind.” It would be subject to regulation by a UN body, the International Seabed Authority, which would license commercial exploitation and collect royalties from operators.

So far, this was broadly consistent with the U.S. policy.

But, as proposed, this “Authority” also would operate its own company, identified as the “Enterprise,” to conduct deep seabed mining, alongside commercial operators.

“Enterprise” profits then would be distributed among member states on the basis of “equitable sharing,” with particular regard for the interests of developing and landlocked states.

Member states would be required to transfer their technology to this “Enterprise” and to “developing countries” to allow them to engage in seabed mining alongside established operators.

The then-chief negotiator for the United States at UNCLOS III, U.S. Ambassador Elliot Richardson (a former U.S. Attorney-General) declared these features “fundamentally unacceptable,” but remained at the UNCLOS III bargaining table, in the hopes of reaching better terms.

Meanwhile, members of Congress stepped up efforts to pass domestic legislation to permit deep seabed mining unilaterally, and in late 1977 the Carter Administration indicated it would support this.

In 1979, a robust bill allowing the U.S. government to license seabed mining was being actively considered by Congress.

Thus, in the space of fewer than 10 years, U.S. policymakers had shifted from supporting a multilateral treaty system for seabed mining, overseen by an international body (the Nixon proposal of 1972) to favoring a unilateral regulatory system, with the U.S. regulating U.S. mining activities on the deep seabed.

But, as will be seen, this did not prevent the rest of the world from moving forward with a comprehensive treaty, despite growing discomfort with that model within the U.S.

During the 1970s, a U.N. conference, “UNCLOS III,” was commissioned to draft a comprehensive Law of the Sea Convention, (“LOSC”), to regulate, among other things, the the deep seabed.

Though initially, this had White House support, things changed in 1977, when the treaty text took a leftward turn — providing for seabed mining to be governed by a central U.N.-affiliated “Authority,” whose “Enterprise” would also engage in mining itself, with profits distributed to developing states, on the basis that the seabed was the “common heritage of mankind.”

Members of Congress reacted by sponsoring legislation to regulate seabed mining unilaterally, via U.S.

government licensing.

In 1979, this legislation was being actively considered.

In that same year, yet another treaty text, from another UN body — the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs — sent critics of the draft LOSC into overdrive.

Titled the “Moon Agreement,” this too described both the Moon and all celestial bodies as “common heritage of mankind,” and envisaged a system whereby an international regulator would license and supervise the exploitation of outer space.

One U.S. critic (future Secretary of State Alexander Haig) complained that the treaty “would doom any private investment directed at space resource exploration.”

It was clear that attitudes towards the “common heritage of mankind” formula had changed.

In 1970, when the Nixon administration declared the deep seabed to be the “common heritage of mankind,” the phrase was little more than a political bromide.

By decade’s end, the phrase was viewed as socialistic.

Not that the Group of 77 was blind to market forces: Part XI of LOSC (both in its draft and final versions) included a carefully-crafted set of production ceilings for the minerals expected to be extracted from the deep seabed (namely, nickel, manganese, copper and cobalt).

This was apparently intended to protect developing countries from the adverse price effects (to their economies) from such minerals becoming more abundant.

It thus was not surprising that Congress enacted the “Deep Seabed Hardbed Mineral Resources Act” of 1980 to facilitate U.S. commercial mining on the ocean floor without U.N. or international approval, based on licenses issued by a U.S. regulator.

In 1982, President Reagan issued a national security directive stating that he would only support a treaty that “will not deter development of any deep seabed mineral resources to meet national and world demand” and “[would] give the United States a decision-making role in the deep seabed regime that fairly reflects and effectively protects its political and economic interests and financial contributions.”

government licensing.

In 1979, this legislation was being actively considered.

In that same year, yet another treaty text, from another UN body — the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs — sent critics of the draft LOSC into overdrive.

Titled the “Moon Agreement,” this too described both the Moon and all celestial bodies as “common heritage of mankind,” and envisaged a system whereby an international regulator would license and supervise the exploitation of outer space.

One U.S. critic (future Secretary of State Alexander Haig) complained that the treaty “would doom any private investment directed at space resource exploration.”

It was clear that attitudes towards the “common heritage of mankind” formula had changed.

In 1970, when the Nixon administration declared the deep seabed to be the “common heritage of mankind,” the phrase was little more than a political bromide.

By decade’s end, the phrase was viewed as socialistic.

Not that the Group of 77 was blind to market forces: Part XI of LOSC (both in its draft and final versions) included a carefully-crafted set of production ceilings for the minerals expected to be extracted from the deep seabed (namely, nickel, manganese, copper and cobalt).

This was apparently intended to protect developing countries from the adverse price effects (to their economies) from such minerals becoming more abundant.

It thus was not surprising that Congress enacted the “Deep Seabed Hardbed Mineral Resources Act” of 1980 to facilitate U.S. commercial mining on the ocean floor without U.N. or international approval, based on licenses issued by a U.S. regulator.

In 1982, President Reagan issued a national security directive stating that he would only support a treaty that “will not deter development of any deep seabed mineral resources to meet national and world demand” and “[would] give the United States a decision-making role in the deep seabed regime that fairly reflects and effectively protects its political and economic interests and financial contributions.”

Later that year, the United States signed a series of bilateral treaties with its major trading partners that provided for mutual recognition of their mining legislation and rights.

In December 1982, the final LOSC text was presented for signature at the ceremonial final meeting of UNCLOS III in Montego Bay.

Despite some modifications, Part XI of the text retained many controversial features from the 1977 draft– including the strong central Seabed Authority, its operating “Enterprise,” its profit redistribution rules, and mandatory “technology transfer” provisions obligating Western operators to share their seabed mining technology with the Enterprise and developing nations.

Many countries, including Western states, signed LOSC, but the United States did not.

For some, the U.S. refusal to sign LOSC was a disappointment, since LOSC had many features that were beneficial to U.S. maritime, naval and commercial interests.

Despite discomfort with Part XI, non-adherence came at a potentially heavy price, since it put U.S.

mining interests outside the treaty’s protection.

As the former U.S. chief negotiator, Elliot Richardson, pointed out in 1983:

Domestic United States law cannot confer on anyone a generally recognized legal right to exploit a defined area of the seabed.

But without such a right good for at least twenty years, no rational investor will gamble $1.5 billion on a deep seabed mining project.

It will not suffice for seabed mining claims to be recognized only by a handful of like-minded countries.

And even the seabed mining States concede that international law would not require non-members of the reciprocal regime to respect it.

As to Mr. Richardson’s estimate of a $1.5 billion dollar cost of seabed mining, it may have been conservative.

The supposedly original seabed drill ship, Hughes Glomar Explorer, cost over $800 million, if not more, in 1970s dollars.

In December 1982, the final LOSC text was presented for signature at the ceremonial final meeting of UNCLOS III in Montego Bay.

Despite some modifications, Part XI of the text retained many controversial features from the 1977 draft– including the strong central Seabed Authority, its operating “Enterprise,” its profit redistribution rules, and mandatory “technology transfer” provisions obligating Western operators to share their seabed mining technology with the Enterprise and developing nations.

Many countries, including Western states, signed LOSC, but the United States did not.

For some, the U.S. refusal to sign LOSC was a disappointment, since LOSC had many features that were beneficial to U.S. maritime, naval and commercial interests.

Despite discomfort with Part XI, non-adherence came at a potentially heavy price, since it put U.S.

mining interests outside the treaty’s protection.

As the former U.S. chief negotiator, Elliot Richardson, pointed out in 1983:

Domestic United States law cannot confer on anyone a generally recognized legal right to exploit a defined area of the seabed.

But without such a right good for at least twenty years, no rational investor will gamble $1.5 billion on a deep seabed mining project.

It will not suffice for seabed mining claims to be recognized only by a handful of like-minded countries.

And even the seabed mining States concede that international law would not require non-members of the reciprocal regime to respect it.

As to Mr. Richardson’s estimate of a $1.5 billion dollar cost of seabed mining, it may have been conservative.

The supposedly original seabed drill ship, Hughes Glomar Explorer, cost over $800 million, if not more, in 1970s dollars.

Glomar Explorer mothballed in Suisun Bay, California, during June 1993.

Glomar Explorer mothballed in Suisun Bay, California, during June 1993. During the 1980s and early 1990s, the United States’ “holdout” status was immaterial because the LOSC still had not been ratified by enough countries.

But on November 16, 1993, Guyana became the sixtieth state to ratify, meaning LOSC would take effect on November 16, 1994.

The Seabed Authority, and all of its associated treaty machinery, was to spring into life.

Having failed to stop the LOSC, and the Seabed Authority, from coming into existence, the U.S.

and other Western nations hurriedly negotiated a reconciliation package to ameliorate the more troublesome features of Part XI and the Seabed Authority structure, and thus enable the U.S. to enter the LOSC.

In June 1994, the U.S. and other countries endorsed an “Agreement on Implementation” of Part XI, creating a more market-friendly regime for the seabed.

This reduced the license application fee, reduced funding for the so-called “Enterprise,” abolished production ceiling rules, made seabed activity subject to GATT rules, and dropped mandatory technology transfer.

It further provided for voting on the Seabed Authority to be done in groups, with the U.S. virtually guaranteed a seat on such groups — and placed all key financial decisions in the hands of a Finance Committee, in which the largest donors would automatically be members and decisions would be based on consensus.

The Clinton Administration signed both the “Implementation Agreement” and the LOSC in mid-1994, in the hope that the Senate would soon ratify it.

This never occurred, however.

Despite bipartisan support for LOSC (including from the second Bush administration), it has continued to draw enough criticism to make a ratification vote nonviable.

In 2012, for example, over 33 Senators indicated they would oppose ratification, citing concerns over the Seabed Authority’s powers, as well as other objections to the LOSC.

Yet the LOSC exists, and since November 1994, the Seabed Authority has been the international regulator of the deep seabed.

Based in Montego Bay, and with all of the trappings of U.N. bureaucracy — an “Assembly,” a “Council” and its own Secretariat — the Seabed Authority has granted various licenses to explore for polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich ferromanganese, polymetallic sulfides.

Most of these licenses have centered in the zone of the Pacific known as the “Clarion-Clipperton Zone,” just southwest of Hawaii.

The Seabed Authority has yet to grant actual mineral exploitation licenses.

Its “Mining Code” — rules to govern the actual extraction of seabed minerals — has been the subject of ongoing internal debate since 2018.

Once finalized, however, the path will be open for mining licenses to issue.

Notably also, while some exploration contracts have gone to Western applicants (e.g., German and British operators), others have gone to applicants from or supported by Cuba, Russia and China (see https://isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/polymetallic-nodules).

U.S. players are conspicuously absent.

While the Seabed Authority’s work has largely escaped public attention, its work remains important, not just because of the intrinsic value of the minerals in question, but also because the environmental significance of the deep seabed, and its ecosystems, has come to be far better understood.

Critics have even accused the Seabed Authority of having an inherent conflict of responsibilities, in that it oversees both mining and environmental issues.

All of this, moreover, is occurring without active involvement of the U.S. — which, as a non-party to the LOSC, has no say in the Seabed Authority’s governance — all at a time when supply chain uncertainty and renewed international tensions have re-ignited concerns over access to natural resources.

What, then, became of the Hughes Glomar Explorer — the vessel whose 1974 expedition, for many, started the debate over deep seabed mining?

Did it find manganese nodules on the sea floor, and if so, did it extract and sell them?

How did the U.S. steal a sunken nuclear submarine?

Right out from under the nose of the Soviet Union...

Cool thumb details: The Hughes Mining Barge, or HMB-1, is a submersible barge about 99 m (324 ft) long, 32 m (106 ft) wide, and more than 27 m (90 ft) tall.

The HMB-1 was originally developed as part of Project Azorian (more widely, but erroneously, known as "Project Jennifer"), the top-secret effort mounted by the Central Intelligence Agency to salvage the remains of the Soviet submarine K-129 from the ocean floor.

The HMB-1 was designed to allow the device that would be used to grasp and lift the submarine to be constructed inside the barge and out of sight, and to be installed in the Glomar Explorer in secrecy.

This was done by towing the HMB-1, with the capture device inside, to a location near Catalina Island (off the coast of California), and then submerging it onto stabilizing piers that had been installed on the seafloor.

The Glomar Explorer was then maneuvered over the HMB-1, the retractable roof was opened, and the capture device lifted into the massive "moon pool" of the ship, all within clear sight of people on the beach ------- It’s March 1968.

An unexplained event causes a Soviet Golf-II submarine known as the K-129 to sink to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean while enroute to its patrol station off the coast of Hawaii.

Publicly, no one in the world knew what happened, where the submarine was, or what secrets might be hidden on board.

Behind the scenes, however, reporters caught wind of a classified US government operation to pry the wreckage from the floor with a giant claw and uncover whatever secret technology might be hidden within.

The mission was codenamed Project Azorian, and it was launched from a covert ship named the Glomar Explorer.

Pressed for comment on the operation, a US government spokesman flatly replied, [quote] “We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested but, hypothetically, if such data were to exist, the subject matter would be classified, and could not be disclosed…"

It was purpose-built by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency as part of “Project Azorian,” a covert, mission to find and raise a sunken Soviet nuclear submarine (the K-129) that had been lost in the North Pacific in 1969.

The mission was partly successful, with portions of the submarine raised in August 1974 — following which, the Glomar Explorer was mothballed.

The vast expense of the mission ( over $800 million) is still keenly debated among Cold War historians.

Despite its fanfare, therefore, the Hughes Glomar Explorer was not a pioneer of seabed mining.

Although large scale seabed mining has not begun, policymakers, including in the United States, will soon be faced with some hard questions.

The deep seabed covers literally two-thirds of the world’s surface.

If robotic technology continues to accelerate, if commodity prices rise and if supply chain uncertainty intensifies, the issue of how and whether to mine the ocean floor — and how to deal with rival attempts to mine it — may become a topic of real and pressing concern.

Although large scale seabed mining has not begun, policymakers, including in the United States, will soon be faced with some hard questions.

The deep seabed covers literally two-thirds of the world’s surface.

If robotic technology continues to accelerate, if commodity prices rise and if supply chain uncertainty intensifies, the issue of how and whether to mine the ocean floor — and how to deal with rival attempts to mine it — may become a topic of real and pressing concern.

Links :

- Business Insider : How the CIA teamed up with a reclusive billionaire for a secret mission to raise a Soviet submarine sunk 3 miles under the ocean

- Smithsonian : During the Cold War, the CIA Secretly Plucked a Soviet Submarine From the Ocean Floor Using a Giant Claw

- PopMechanics : 5 Things About America's Daredevil Mission to Salvage a Soviet Nuclear Sub

- WAMU : ‘The Taking Of K-129’: How The CIA Stole A Sunken Soviet Sub Off The Ocean Floor / How The CIA Found A Soviet Sub — Without The Soviets Knowing

- GeoGarage blog : The secret on the ocean floor : deep-sea mining / The future of technology is hiding on the ocean floor / The deep sea is filled with treasure, but it comes at a price /

Historic navy ship for sale

No comments:

Post a Comment