From The Register by Gareth Corfield

Following the Fleet Navigating Officers' course

The art of not driving your warship into the coast or the seabed is a curious blend of the ancient and the very modern, as The Regdiscovered while observing the Royal Navy's Fleet Navigating Officers' (FNO) course.

Safe navigation at sea is vital for all mariners and the Admiralty manual of navigation captures centuries of @RoyalNavy experience in this field.

Held aboard HMS Severn, "sea week" of the FNO course involves taking students fresh from classroom training and putting them on the bridge of a real live ship – and then watching them navigate through progressively harder real-life challenges.

"It's about finding where the students' capacity limit is," FNO instructor Lieutenant Commander Mark Raeburn told The Register.

Safety comes first: the Navy isn't interested in having navigators who can't keep up with the pressures and volume of information during pilotage close to shore – or near enemy minefields.

"It's about finding where the students' capacity limit is," FNO instructor Lieutenant Commander Mark Raeburn told The Register.

Safety comes first: the Navy isn't interested in having navigators who can't keep up with the pressures and volume of information during pilotage close to shore – or near enemy minefields.

So the student navigator hopes, anyway.

Driving (all of the officers we spoke to aboard Severn referred to it as driving and not sailing or steaming) a warship, as we reported during the course itself, is a highly skilled art that depends on precisely planning what you want the ship to do – and then having a clear enough mind to modify that plan on the fly depending on what the outside world is doing.

Second Officer Will Salloway, 26, a Royal Fleet Auxiliary* student on the FNO course, told The Register: "There's a lot of planning to do in a short timeframe.

That can be quite tough, coming out with a safe plan which has everything you need in it while being able to manage the pressures… you spend three hours on bridge managing the runs, on top of that and planning you've gotta eat and sleep."

"It's probably 20 times as much planning to execution."

Bobbin' on the oggin'

The essence of the FNO course is safely taking the ship to and from an anchorage, or navigating through tricky inshore waters, while maintaining appropriate safety margins.

For a surface ship this means staying away from a not-quite-imaginary line of critical importance: the Limiting Danger Line, or LDL.

The LDL is a depth that must never be passed in case the ship runs aground.

It's calculated by adding the ship's keel depth plus the squat for her planned speed** plus a margin on top, and then drawing "do not cross" lines on the chart.

Each FNO student plans and carries out six live navigation runs in control of the Severn: three "development" passages with FNO instructors coaching them throughout and giving them feedback, and three exam runs where assessors specially embarked for the course quietly watch the students going through their paces and decide if they pass or fail.

The ship herself travelled along Britain's south coast, dipped in and out of Plymouth and then dropped south to the Channel Islands' large tides and tidal stream variations before returning to her home base at Portsmouth.

The course concentrates on navigating a ship without GPS.

Taking away the external you-are-here service leaves the navigator aboard Severn with three manually sighted gyro-compasses*** and the heart of naval navigation, the Warship Electronic Chart Display and Information System (WECDIS, pronounced by all as "weck-diss").

Naval pilotage means planning a precise track from a position out at sea to an anchorage – or from an anchorage back out to sea, following a marked channel or passing through an area with a strong tidal stream and lots of other maritime traffic.

The navigator then keeps the ship to within yards of her planned track and turning points along the track.

On top of that, the navigator also plans wheel-over points; the spot where the wheel must be turned to a set angle so the ship precisely meets the next planned leg.

In this regard, naval pilotage planning is an exacting science.

Contact with the real world's weather and tides introduces an element of "fun" as one instructor whimsically observed.

For the student navigator, fixing your position means putting two of your fellow students on the external gyro-compasses to call out bearings, a third on the surface radar and a fourth on the WECDIS console, mounted in Severn behind the central gyro-compass on the ship's pelorus.

That team then works the maths and the technology together, all in perfect harmony with the navigator's prepared passage plan.

Taking bearings off shore landmarks or nautical navigation marks (lighthouses and prominent buildings by day, flashing lights by night) with a gyro-compass hasn't changed much since compasses were introduced to seafaring: you look down the compass towards the mark, read off the bearing and record it.

Severn's concession to modernity is that her gyro-compasses have a modest internal telescope and illumination for night readings.

Yet in modern naval navigation, that ancient art of eyeballing the bearings is married to a modern computer system that constantly integrates and updates bearings to produce a live plot of where the ship ought to be.

It's a curious blend of an old art with up-to-date technology that complements both: for eyes used to instantly seeing the answers to life, the universe and everything presented on a computer, the digital displays telling the bridge crew where the ship is located are curiously reassuring.

Reading bearings to navigation marks would be equally familiar to sailors from the mid-19th century.

During the course safety comes first: the captain and instructors can see a GPS-enabled WECDIS display showing precisely where the ship is, and can intervene if something unsafe is about to happen.

We've got windows – glass ones, not the operating system

Although the FNO course is usually loaded with eight students, during the week that El Reg joined the Severn we had just four: two from the surface fleet; one from submarines; and one from the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA).

Severn's captain, Commander Philip Harper, mused that each student's professional naval experience brought something different to their navigational technique.

For example, submarine navigation normally takes place underwater, so submariner students on the FNO course tend to start off by gazing at the screens on the bridge instead of looking outside.

Lieutenant Jack Crallan, a 32-year-old submariner who was a physics teacher before joining the Navy, agreed: "Biggest difference for me is being able to see things! I'm usually looking at my notebook and listening to the numbers and not looking out of the window.

But on a submarine the only information you have is bearings."

Although the process of pilotage (navigation close to shore) is inherently mathematical, the FNO students insisted you didn't need to be a numerical genius to keep the ship safe ("I got a U in A-level maths," joked one).

Lieutenant Matt Cavill, 29, who has a degree in molecular cell biology, said of the above quick-reference tables: "When someone works out a distance off track or a distance to run, that's all done off a single bearing in their notebook most likely.

When someone works out a time to regain, or a distance to regain, then they are using mental maths but it's fairly basic – some people can do speed/distance/time [on the fly], it comes relatively easily to me.

I do have a note of easy numbers, though!"

Fellow student Lt Crallan added: "There are a lot of maths tricks as well.

We tend to do something of 12 or 15 or 30 very easily; that's the sine rule.

You can do trigonometry in your head if you pick the right numbers."

Staying in clear water

On the FNO course it's not enough to leave the maths to WECDIS.

From watching the navigation runs, it was clear that whoever was navigating was expected to use the electronic plot to help them form their own mental picture of where the ship was at any given moment, not as a crutch for leaning on.

To the non-nautical observer, RN pilotage is a bewildering verbal stream of bearings, marks, yards, chains, timings, and jargon.

The WECDIS operator is constantly updating bearings on his console behind the navigator, who occasionally darts from the pelorus to a bridge window or shouts "heads" so everyone in front of him ducks while he's taking a sighting.

Outside the bridge his fellow students use loudspeakers to call bearings in – whether once, on request when two landmarks pass in transit (in line with each other) or (most often) in a regular stream.

Beside the navigator, in a large and comfortable chair, sits the captain – or his right-hand man, the ship's executive officer, with whom he alternates during FNO runs and debriefs.

The navigator's job is to keep the captain updated on what he's doing; RN captains are often not qualified navigators themselves.

Salloway explained: "If you're the nav of a ship, that's what it's like for real.

If your CO [commanding officer] is busy… all while you're driving a possibly inexperienced team, going into a port you're not familiar with where there could be certain risks or threats.

Being able to be in the position we're in now, a safe training environment… It's really helpful for the future."

As well as the "simple" navigation challenge, the course puts its students through a serious test of nerve in the Solent.

On a calm and sunny Friday this stretch of sea, captured between the Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and Southampton, plays host to scores of small sailing boats and powered vessels.

Keeping to the planned navigation track in the Solent becomes an exercise in instinctively knowing the nautical Rules of the Road, keeping radio calls to, from and between other traffic in mind – and knowing how to navigate back on track after cutting a corner or extending a leg to safely avoid another vessel.

The students made it look effortless even as your correspondent tried and failed to follow the basic navigation plot by gazing at the WECDIS screen.

"Why am I doing this, or why would I do this in future?" mused Lt Dom Jacobs, 24, one of the FNO students.

"If you're running along an enemy coastline, blacked out, running along so you can get the main weapon into arcs so you can shoot [along] that river or feature… it gives us confidence.

It's all good things to help build capacity for when it all goes wrong – or we're at war.

Because that's what we're here for."

It might seem from an outside glance that naval navigation would depend on technology but, putting aside the speed and spare mental capacity that WECDIS gives the navigator, it's really a very low-tech endeavour.

"You should see the specialist navigator course," remarked one of the FNO instructors during a night-time run.

"They use sextants."

Perhaps if there's a next time...

The Register thanks the Royal Navy, in particular: Commander Philip Harper, CO of HMS Severn; the warm and welcoming ship's company of HMS Severn; and the ever-patient students and directing staff of the Fleet Navigating Officer's Course.

Bootnotes

RN Navigation Training Unit

Driving (all of the officers we spoke to aboard Severn referred to it as driving and not sailing or steaming) a warship, as we reported during the course itself, is a highly skilled art that depends on precisely planning what you want the ship to do – and then having a clear enough mind to modify that plan on the fly depending on what the outside world is doing.

HMS Severn's pelorus, mounted centrally on the bridge

Second Officer Will Salloway, 26, a Royal Fleet Auxiliary* student on the FNO course, told The Register: "There's a lot of planning to do in a short timeframe.

That can be quite tough, coming out with a safe plan which has everything you need in it while being able to manage the pressures… you spend three hours on bridge managing the runs, on top of that and planning you've gotta eat and sleep."

"It's probably 20 times as much planning to execution."

Bobbin' on the oggin'

The essence of the FNO course is safely taking the ship to and from an anchorage, or navigating through tricky inshore waters, while maintaining appropriate safety margins.

For a surface ship this means staying away from a not-quite-imaginary line of critical importance: the Limiting Danger Line, or LDL.

The LDL is a depth that must never be passed in case the ship runs aground.

It's calculated by adding the ship's keel depth plus the squat for her planned speed** plus a margin on top, and then drawing "do not cross" lines on the chart.

Each FNO student plans and carries out six live navigation runs in control of the Severn: three "development" passages with FNO instructors coaching them throughout and giving them feedback, and three exam runs where assessors specially embarked for the course quietly watch the students going through their paces and decide if they pass or fail.

The ship herself travelled along Britain's south coast, dipped in and out of Plymouth and then dropped south to the Channel Islands' large tides and tidal stream variations before returning to her home base at Portsmouth.

The view down HMS Severn's pelorus-mounted gyrocompass

The course concentrates on navigating a ship without GPS.

Taking away the external you-are-here service leaves the navigator aboard Severn with three manually sighted gyro-compasses*** and the heart of naval navigation, the Warship Electronic Chart Display and Information System (WECDIS, pronounced by all as "weck-diss").

Naval pilotage means planning a precise track from a position out at sea to an anchorage – or from an anchorage back out to sea, following a marked channel or passing through an area with a strong tidal stream and lots of other maritime traffic.

The navigator then keeps the ship to within yards of her planned track and turning points along the track.

On top of that, the navigator also plans wheel-over points; the spot where the wheel must be turned to a set angle so the ship precisely meets the next planned leg.

In this regard, naval pilotage planning is an exacting science.

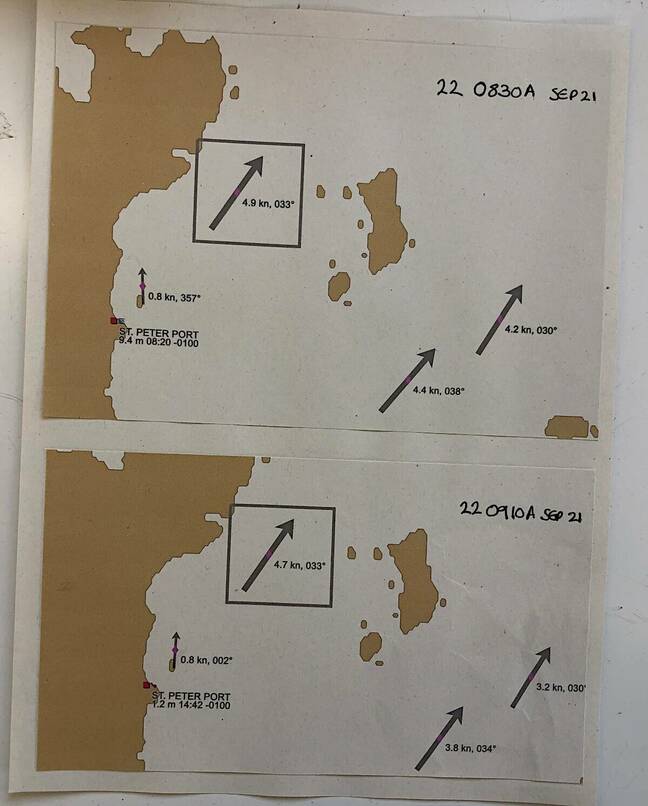

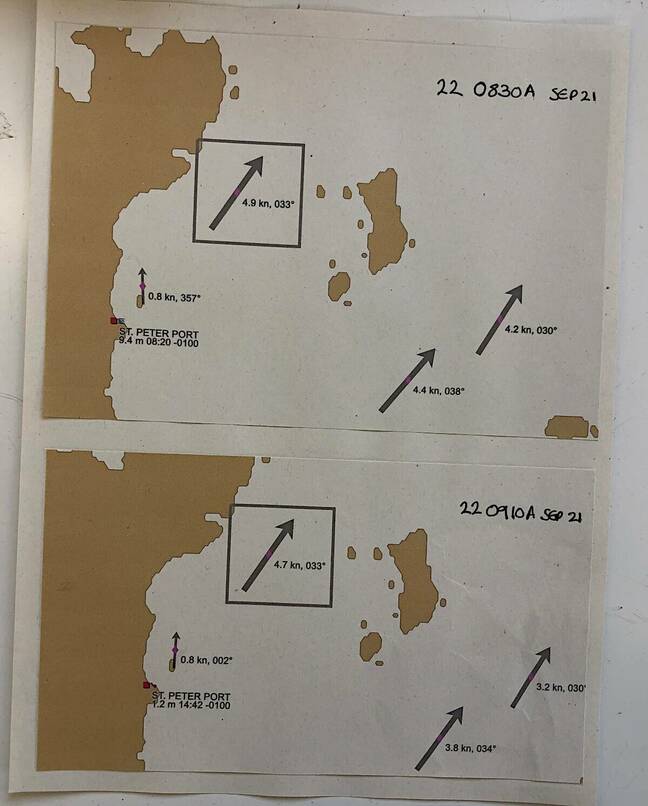

Tidal stream predictions off St Peter Port, Guernsey

Contact with the real world's weather and tides introduces an element of "fun" as one instructor whimsically observed.

For the student navigator, fixing your position means putting two of your fellow students on the external gyro-compasses to call out bearings, a third on the surface radar and a fourth on the WECDIS console, mounted in Severn behind the central gyro-compass on the ship's pelorus.

That team then works the maths and the technology together, all in perfect harmony with the navigator's prepared passage plan.

HMS Severn's bridge radar plot.

One of the FNO students keeps an eye on nearby ships and the coast, seen as the big yellow line

One of the FNO students keeps an eye on nearby ships and the coast, seen as the big yellow line

Taking bearings off shore landmarks or nautical navigation marks (lighthouses and prominent buildings by day, flashing lights by night) with a gyro-compass hasn't changed much since compasses were introduced to seafaring: you look down the compass towards the mark, read off the bearing and record it.

Severn's concession to modernity is that her gyro-compasses have a modest internal telescope and illumination for night readings.

A navigation buoy marking the channel into Plymouth harbour

Yet in modern naval navigation, that ancient art of eyeballing the bearings is married to a modern computer system that constantly integrates and updates bearings to produce a live plot of where the ship ought to be.

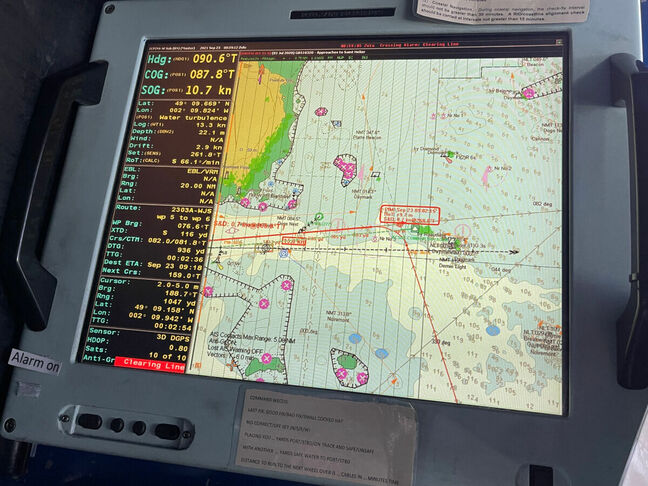

A WECDIS screen aboard HMS Severn.

It's a curious blend of an old art with up-to-date technology that complements both: for eyes used to instantly seeing the answers to life, the universe and everything presented on a computer, the digital displays telling the bridge crew where the ship is located are curiously reassuring.

Reading bearings to navigation marks would be equally familiar to sailors from the mid-19th century.

During the course safety comes first: the captain and instructors can see a GPS-enabled WECDIS display showing precisely where the ship is, and can intervene if something unsafe is about to happen.

We've got windows – glass ones, not the operating system

Although the FNO course is usually loaded with eight students, during the week that El Reg joined the Severn we had just four: two from the surface fleet; one from submarines; and one from the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA).

Severn's captain, Commander Philip Harper, mused that each student's professional naval experience brought something different to their navigational technique.

For example, submarine navigation normally takes place underwater, so submariner students on the FNO course tend to start off by gazing at the screens on the bridge instead of looking outside.

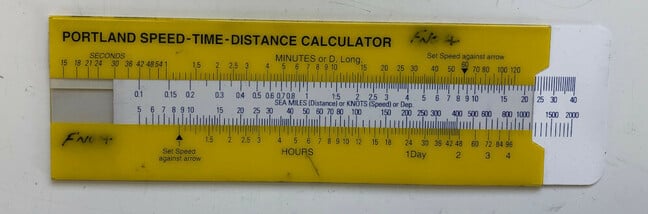

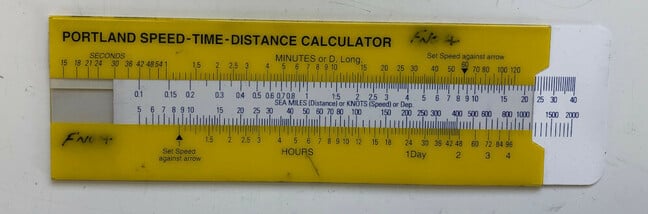

Portland speed/distance/time analogue calculator, used on the FNO course

Lieutenant Jack Crallan, a 32-year-old submariner who was a physics teacher before joining the Navy, agreed: "Biggest difference for me is being able to see things! I'm usually looking at my notebook and listening to the numbers and not looking out of the window.

But on a submarine the only information you have is bearings."

Although the process of pilotage (navigation close to shore) is inherently mathematical, the FNO students insisted you didn't need to be a numerical genius to keep the ship safe ("I got a U in A-level maths," joked one).

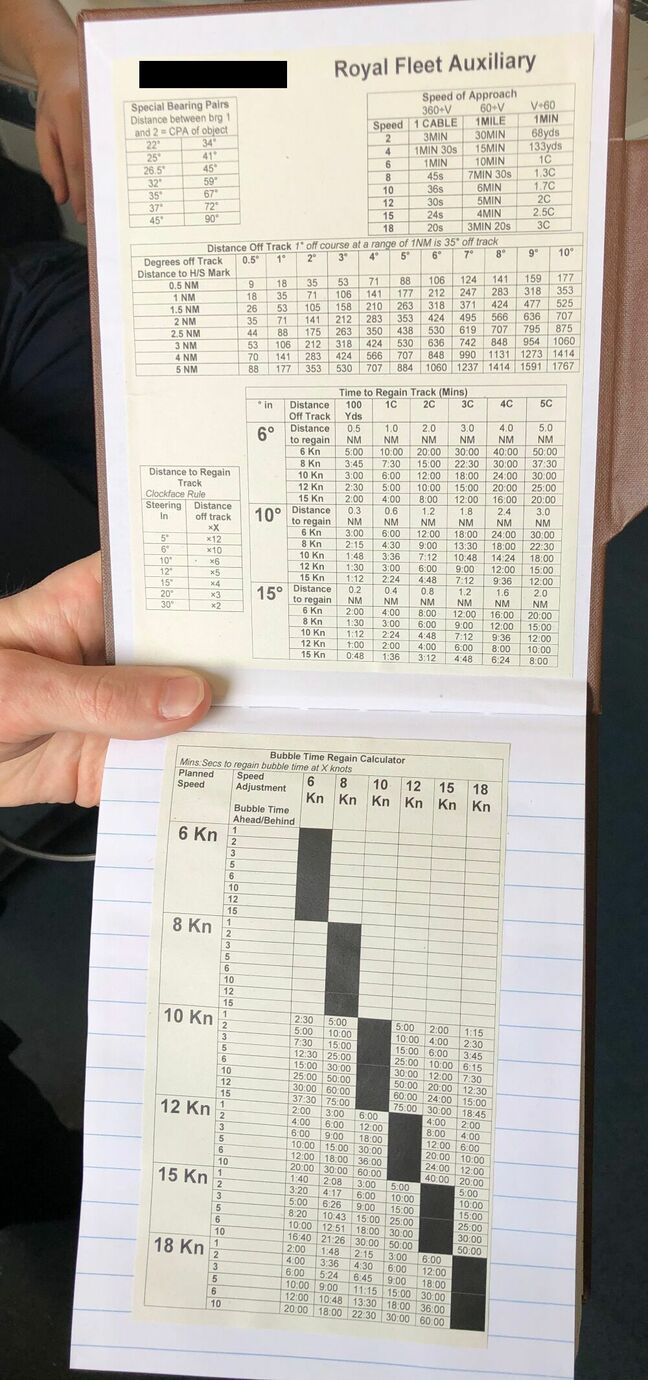

Royal Fleet Auxiliary navigator's notebook and quick-reference table

Lieutenant Matt Cavill, 29, who has a degree in molecular cell biology, said of the above quick-reference tables: "When someone works out a distance off track or a distance to run, that's all done off a single bearing in their notebook most likely.

When someone works out a time to regain, or a distance to regain, then they are using mental maths but it's fairly basic – some people can do speed/distance/time [on the fly], it comes relatively easily to me.

I do have a note of easy numbers, though!"

Fellow student Lt Crallan added: "There are a lot of maths tricks as well.

We tend to do something of 12 or 15 or 30 very easily; that's the sine rule.

You can do trigonometry in your head if you pick the right numbers."

Staying in clear water

On the FNO course it's not enough to leave the maths to WECDIS.

From watching the navigation runs, it was clear that whoever was navigating was expected to use the electronic plot to help them form their own mental picture of where the ship was at any given moment, not as a crutch for leaning on.

To the non-nautical observer, RN pilotage is a bewildering verbal stream of bearings, marks, yards, chains, timings, and jargon.

The WECDIS operator is constantly updating bearings on his console behind the navigator, who occasionally darts from the pelorus to a bridge window or shouts "heads" so everyone in front of him ducks while he's taking a sighting.

Outside the bridge his fellow students use loudspeakers to call bearings in – whether once, on request when two landmarks pass in transit (in line with each other) or (most often) in a regular stream.

HMS Severn's captain, Cdr Philip Harper, observes a nearby ship.

Note the "cone of shame" over the ship's master GPS-enabled WECDIS plot so the student navigator (standing behind Cdr Harper) can't cheat

Note the "cone of shame" over the ship's master GPS-enabled WECDIS plot so the student navigator (standing behind Cdr Harper) can't cheat

Beside the navigator, in a large and comfortable chair, sits the captain – or his right-hand man, the ship's executive officer, with whom he alternates during FNO runs and debriefs.

The navigator's job is to keep the captain updated on what he's doing; RN captains are often not qualified navigators themselves.

Salloway explained: "If you're the nav of a ship, that's what it's like for real.

If your CO [commanding officer] is busy… all while you're driving a possibly inexperienced team, going into a port you're not familiar with where there could be certain risks or threats.

Being able to be in the position we're in now, a safe training environment… It's really helpful for the future."

As well as the "simple" navigation challenge, the course puts its students through a serious test of nerve in the Solent.

On a calm and sunny Friday this stretch of sea, captured between the Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and Southampton, plays host to scores of small sailing boats and powered vessels.

An RAF-liveried motor launch passes HMS Severn on the Solent in September 2021

Keeping to the planned navigation track in the Solent becomes an exercise in instinctively knowing the nautical Rules of the Road, keeping radio calls to, from and between other traffic in mind – and knowing how to navigate back on track after cutting a corner or extending a leg to safely avoid another vessel.

The students made it look effortless even as your correspondent tried and failed to follow the basic navigation plot by gazing at the WECDIS screen.

"Why am I doing this, or why would I do this in future?" mused Lt Dom Jacobs, 24, one of the FNO students.

"If you're running along an enemy coastline, blacked out, running along so you can get the main weapon into arcs so you can shoot [along] that river or feature… it gives us confidence.

It's all good things to help build capacity for when it all goes wrong – or we're at war.

Because that's what we're here for."

It's not all work and no joy aboard the Severn.

Here is the location on the Isle of Wight where Britain's Black Arrow rocket testing programme was based

Here is the location on the Isle of Wight where Britain's Black Arrow rocket testing programme was based

It might seem from an outside glance that naval navigation would depend on technology but, putting aside the speed and spare mental capacity that WECDIS gives the navigator, it's really a very low-tech endeavour.

"You should see the specialist navigator course," remarked one of the FNO instructors during a night-time run.

"They use sextants."

Perhaps if there's a next time...

The Register thanks the Royal Navy, in particular: Commander Philip Harper, CO of HMS Severn; the warm and welcoming ship's company of HMS Severn; and the ever-patient students and directing staff of the Fleet Navigating Officer's Course.

Bootnotes

*The Royal Fleet Auxiliary is the nominally civilian arm of Britain's Naval Service, the military arm being the RN itself.

The RFA runs the Ministry of Defence's fleet of tankers and naval supply vessels that feed, rearm and refuel the Navy at sea.

**When a boat or ship propels herself through water, her stern sinks lower than the rest of the hull depending how fast she's going.

This can be precisely calculated and the Royal Navy has tables for all of its ships giving the squat at known speeds.

***Severn has a sextant hanging on her bridge.

Your correspondent managed to clonk his head on it, mercifully while everyone else was looking the other way.

The RFA runs the Ministry of Defence's fleet of tankers and naval supply vessels that feed, rearm and refuel the Navy at sea.

**When a boat or ship propels herself through water, her stern sinks lower than the rest of the hull depending how fast she's going.

This can be precisely calculated and the Royal Navy has tables for all of its ships giving the squat at known speeds.

***Severn has a sextant hanging on her bridge.

Your correspondent managed to clonk his head on it, mercifully while everyone else was looking the other way.

Links :

- Maritime Executive : UK Integrates Armed, Autonomous Boat Into a Warship's Operations

No comments:

Post a Comment