Venice, one of the cities most at risk, has already installed submerged floodgates aimed at combating flooding, but it’s one of the few to take such preventative action

(Jenny Kim/Public domain)

(Jenny Kim/Public domain)

From Scientific American by Chelsea Harvey

The canals of Venice and an ancient Phoenician city are among the historic sites imperiled by sea level rise and coastal erosion

Climate change is already threatening some of the Mediterranean’s most treasured historical sites, from the iconic Venice canals to the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre.

A jarring new study, published yesterday in the journal Nature Communications, found that more than 90 percent of the region’s World Heritage sites are at risk now from sea-level rise and coastal erosion.

By the end of the century, 47 of the Mediterranean’s 49 sites—and some of the oldest remaining markers of the history of human civilization—will be in jeopardy.

The research highlights the fact that climate change isn’t just a problem for the future and makes the case for more immediate adaptation measures to protect these vulnerable areas.

In some high-risk cases, the scientists suggest governments may even want to consider the possibility of relocating moveable World Heritage sites.

This photo shows the old town of Dubrovnik from a hill above the city.

(Darko Bandic/AP)

The World Heritage, a project of the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), identifies locations around the world that have great cultural or international significance.

They are often areas that stand as testaments to outstanding architectural or technological innovation, artistic achievement, or cultural traditions; that document significant phases in human history; or that possess great natural beauty or ecological importance.

Once a location is designated a World Heritage site, it’s considered a protected area by the United Nations—but its management is up to the nations in which it’s located.

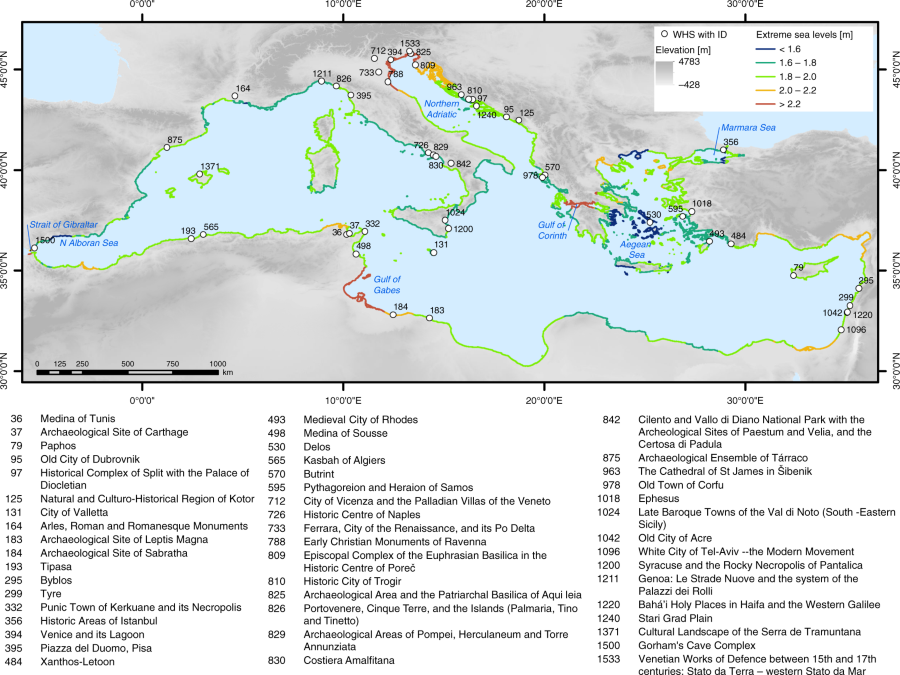

UNESCO cultural World Heritage sites located in the Mediterranean Low Elevation Coastal Zone (LECZ). All sites are shown with their official UNESCO ID and name.

The map also shows extreme sea levels per coastal segment based on the Mediterranean Coastal Database under the high-end sea-level rise scenario in 2100

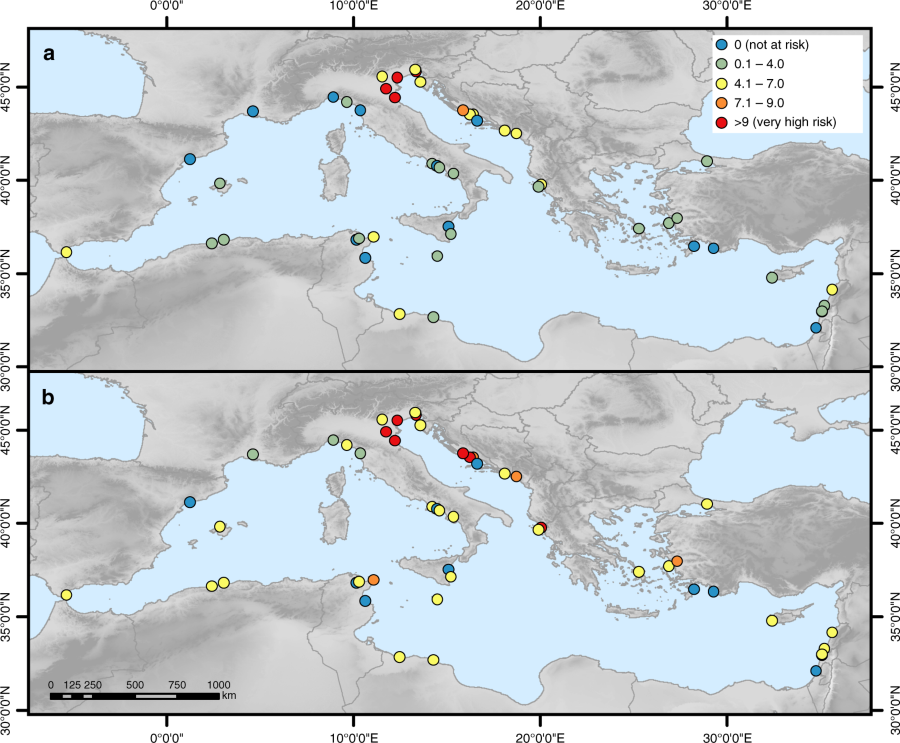

Flood risk index at each World Heritage site under current and future conditions.

a In 2000 and b in 2100 under the high-end sea-level rise scenario

In the new study, the researchers, led by Lena Reimann of Kiel University in Germany, assessed the risk of flooding and coastal erosion at all 49 Mediterranean World Heritage sites under a variety of potential future climate scenarios through 2100.

When considering flooding threats, they evaluated sites based on their risk of experiencing a 100-year flood—that is, a flooding event severe enough that it has only a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year.

Erosion risks were primarily based on a site’s distance from the coastline.

The scientists found that almost all the sites will be at risk, to some extent, from one threat or the other.

The most vulnerable sites to sea-level rise include picturesque Venice, with its network of intersecting canals, as well as the Italian city of Ferrara, a lasting testament to Renaissance culture and urban planning, and the ancient Basilica in the Italian city of Aquileia.

The site most at risk from coastal erosion is the Lebanese city of Tyre, an ancient Phoenician metropolis and cultural hub, which sits on a tiny peninsula jutting directly into the Mediterranean Sea.

Most sites, though, are at risk from both flooding and erosion.

And most sites facing risks in the future are in trouble now.

Those risks will continue to rise throughout the end of the century, particularly under the more severe climate scenarios.

The research underscores several major points, the scientists say.

Large-scale global climate action will be necessary to avoid extreme climate scenarios and prevent as much additional risk to the World Heritage sites as possible.

But immediate adaptation measures—those intended to protect coastal areas from the ongoing influence of sea-level rise and erosion—may also be called for in many locations.

Some of the areas on the list have already begun designing their own adaptation strategies.

The Italian government began work on a system of retractable floodgates in the Venetian Lagoon more than a decade ago.

It’s designed to protect Venice from the impact of storm surge.

But whether it will succeed is another question: The project has been fraught with delays and has yet to be completed.

As time ticks on, the need for concrete action may only become more urgent.

And it’s not just the Mediterranean whose history is at risk of being washed away.

UNESCO began preparing reports and case studies on climate change and global World Heritage sites as far back as 2006 and published a guide for adaptation in 2014.

Other studies have also focused on the effects of climate change on culturally important sites around the world.

One 2014 study in Environmental Research Letters suggests that about 19 percent of World Heritage sites around the world would be threatened by sea-level rise with a temperature increase of 3 degrees Celsius—the warming that might be expected under the current commitments to the Paris climate agreement.

That’s compared with 6 percent with no additional warming.

Other research has taken a more local approach not necessarily limited to UNESCO sites.

A 2014 report published by the Union of Concerned Scientists compiled a collection of case studies focusing on how U.S. national landmarks—including sites such as Ellis Island and Cape Canaveral—might be affected by climate change impacts including sea-level rise and an increase in wildfires.

“As the impacts of climate change continue, we must make hard choices now and take urgent steps to protect these sites and reduce the risks,” the report said.

Links :

- WP : The latest thing climate change is threatening is our history /We’re Covering Heritage Sites Threatened by Climate Change. The List Just Got Longer

- EcoWatch : 8 World Cities That Could Be Underwater as Oceans Rise / Sea Level Rise Could Put 2.4 Million U.S. Coastal Homes at Risk

- Smithsonian : Rising Seas Pose Imminent Threat to Dozens of Historical Sites Across the Mediterranean

- The Verge : The science behind New York City's rising seas

- CityLab : The Dutch Can't Save Us From Rising Seas

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/41/cc/41cc8c31-b809-4bd1-a24d-53bd85e910ca/looking-at-the-grand-canal-of-venice-in-modern-times.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment