Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise in Charlotte Bay, Antarctic peninsula.

Photograph: Christian Åslund/Greenpeace

From The Guardian by Javier Bardem, Oscar-winning actor and an Antarctic ambassador for Greenpeace

The ocean is threatened by climate change, pollution and fishing.

I urge world leaders to agree to establish a sanctuary

I thought it would be cold.

Not just cold, but colder than anything I had experienced in my life.

I had visions of bedraggled explorers in blizzards with ice-covered beards.

But standing there, in the bright Antarctic sun, watching creaking blue icebergs, penguins bursting in and out of the water, I felt utterly content in this glistening wilderness.

A perfectly formed iceberg pictured soon after it broke away from the Larsen C ice shelf

What I hadn’t thought about was the dark.

And not the dark of night – although as a European, that brought a dazzling new astronomy of the southern hemisphere to me – but the dark of the deep, icy, ocean depths.

I was going almost half a kilometre down to the Antarctic seafloor.

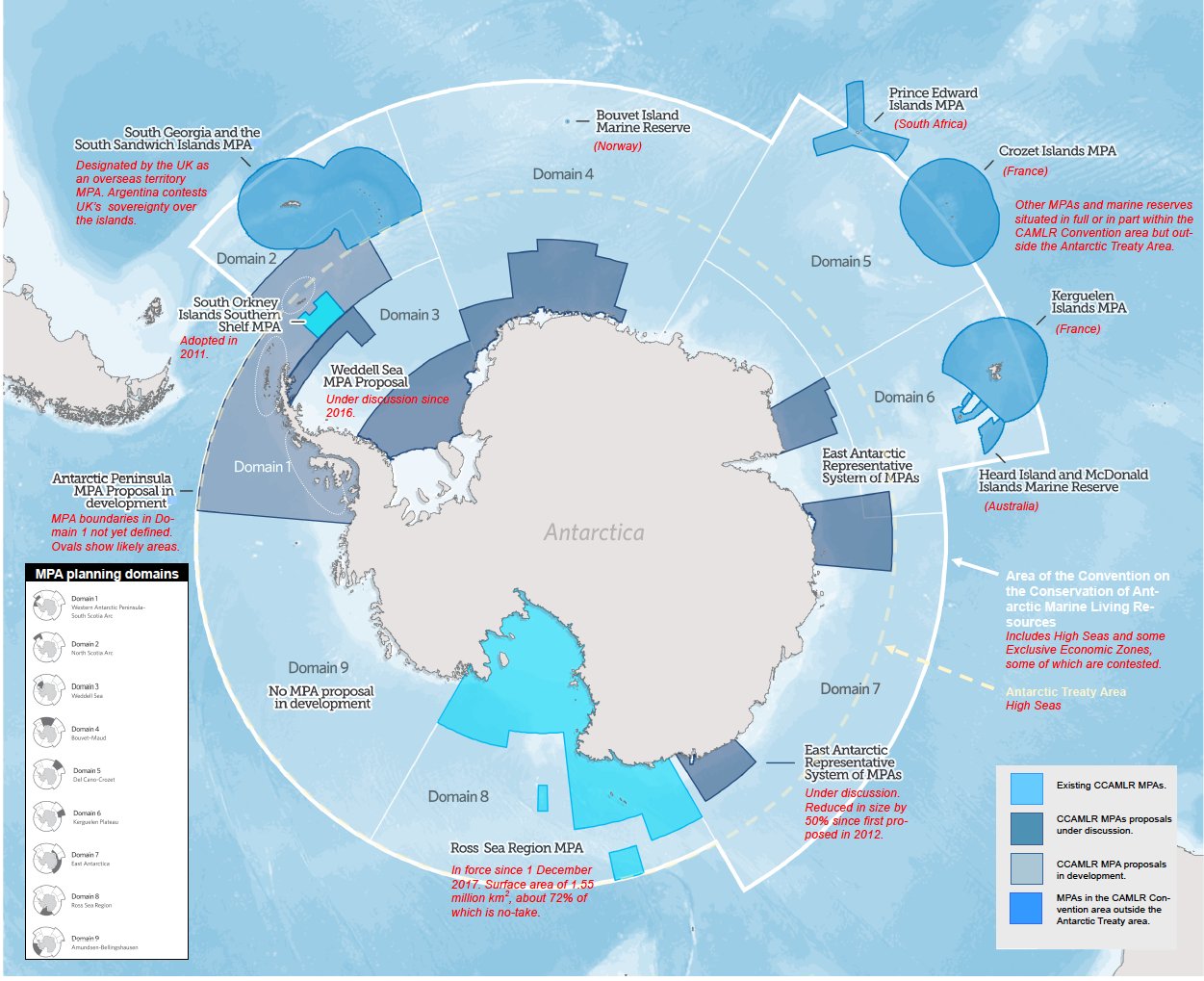

Antarctica MPAs

It was back in January of this year, and I had joined a Greenpeace research expedition as part of a campaign to create a vast Antarctic ocean sanctuary.

At 1.8m square kilometres, it would be five times the size of Germany.

If it’s created, which it could be when governments meet in the next few weeks, it would be the largest protected area anywhere on Earth.

I am one of two million people who want it to happen.

A fracture in the sea ice that is partially refrozen and continuing to re-freeze, known as a lead (Picture: NASA)

Scientists on the ship were using tiny submersibles to go where humans had never been before to explore ecosystems we know so little about: deep habitats they had been looking at on screens all their working lives but had never seen with their own eyes.

The excitement was more arresting than the cold of the Antarctic summer.

So there I was, descending, in a small, two-person submarine to the frontiers of human knowledge.

The light faded, and the sea around us turned a heavy blue.

As we sank to hundreds of metres below the surface, I was surrounded by a thick blackness.

It was a colour that I had no idea the ocean could turn.

Pitch black.

Chinstrap penguins at Orne harbour in the Antarctic.

Photograph: Christian Åslund/Greenpeace

A torch at the front of the submarine shone like a night-light for a child afraid of the dark.

It showed the way to the seabed.

The sight as it came into view was staggering.

Out of the dark and freezing depths emerged a moving, crawling, vibrant mass of life.

The temperature is so low that vegetation barely survives down here.

Nearly everything is an animal: bizarre and ghostly icefish that are semi-transparent; sea spiders that look like something out of a science-fiction film; colourful, tendrilled, feather stars, basket stars, corals, sponges.

I’m told that more people have been to the moon than have been to the bottom of the Antarctic ocean.

Maybe that’s apocryphal, but it certainly feels like it.

We know precious little about this alien environment, which is why it is so crucial to protect it before it is too late.

Emerging back into the light at the surface, the bubbles of the submarine hull clearing, it was like waking from a dream, the intangible creatures of the abyss left far behind.

I had truly seen the light and the dark of the Antarctic.

At its surface, penguin colonies stretch for miles on snow-capped islands, with millions of breeding pairs across the region, raising their chicks in this inhospitable environment.

Enormous whales surface all around, feeding on huge pink clouds of the small shrimp-like krill, which nearly all wildlife here relies on.

Fur seals and elephant seals lounge on drifting blocks of ice.

While below, another world goes on existing in dark vitality.

Underwater view of the submarine Little Planet, part of the Greenpeace expedition.

Photograph: Greenpeace

So often, we lament the destruction of the environment once it has taken place.

And it is true that wildlife in the Antarctic is facing threats from climate change, pollution and industrial fishing.

But this area still remains one of the least-touched regions on the planet.

Right now, we have an opportunity to protect this place.

The governments responsible for conservation of the Antarctic’s waters meet in Hobart, Australia, in the second half of October.

What better conservation of the Antarctic ocean could there be than the creation of the largest protected area on Earth at its heart, in the Weddell sea.

It would put the area off-limits to future human activity, protect wildlife such as penguins, seals and whales, and help to tackle climate change.

The pizza berg in the Weddell Sea with grease ice forming (Picture: Nasa)

I am proud to stand as one person in a movement of more than two million that has come together this year to demand world leaders protect the Antarctic.

Most of these people will never visit the Antarctic, but their passion for protecting it inspires me.

Across the world, people have written to their politicians; they have encouraged their friends and family to take action; they have dressed up as penguins and danced on ice to raise awareness from the streets of Buenos Aires to Beijing; they have installed penguin sculptures from Johannesburg to Seoul.

This is a global movement for a region that belongs to us all.

The mass of the Antarctic ice sheet has changed over the last several years.

Research based on observations from NASA’s twin NASA/German Aerospace Center’s twin Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites indicates that between 2002 and 2016, Antarctica shed approximately 125 gigatons of ice per year, causing global sea level to rise by 0.35 millimeters per year.

These images, created with GRACE data, show changes in Antarctic ice mass since 2002.

Orange and red shades indicate areas that lost ice mass, while light blue shades indicate areas that gained ice mass.

White indicates areas where there has been very little or no change in ice mass since 2002.

In general, areas near the center of Antarctica experienced small amounts of positive or negative change, while the West Antarctic Ice Sheet experienced a significant ice mass loss (dark red) over the fourteen-year period.

Floating ice shelves whose mass GRACE doesn't measure are colored gray.

Now, as governments prepare to meet at the Antarctic ocean commission there are millions of eyes watching them and urging them to act.

To secure the Antarctic for future generations.To allow its abundance of wildlife to flourish and its migratory species to thrive between the world’s oceans.

To help create healthy oceans that contribute to global food security.

To preserve the Antarctic ocean’s functions as one of the world’s largest carbon stores.

Because, truly, what happens in the Antarctic affects us all.

Links :

PopSciences : This geometric iceberg will soothe your soul

ReplyDeleteYouTube : Flight Over a Rectangular Iceberg in the Antarctic (NASA)

ReplyDelete