Perhaps no event in the last 50 years, aside from man’s

landing on the moon, has stirred the imaginations of people everywhere

as much as the famous transatlantic flight of Captain Charles A.

Lindbergh on the 20th of May 1927.

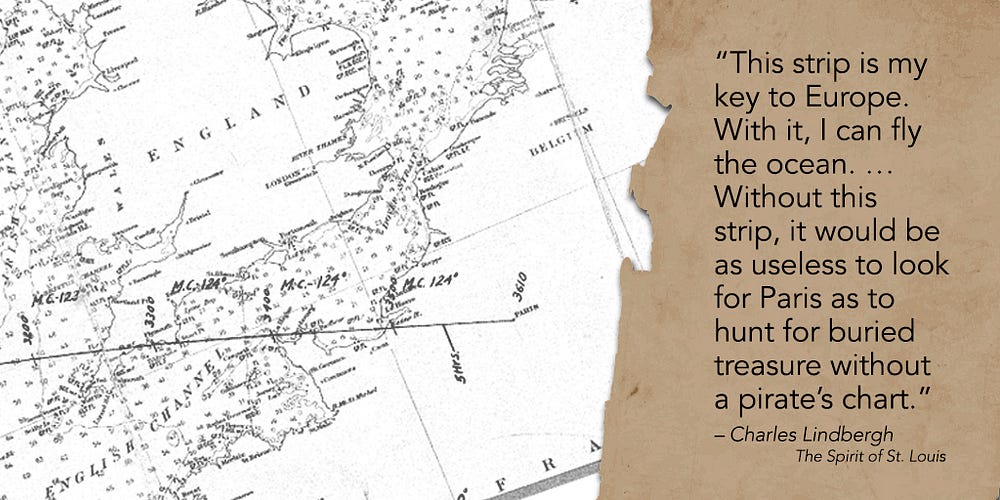

Map image provided by the Missouri History Museum.

Graphic by Beth Neise, NGA Office of Corporate Communications

From Medium by Jessica Daues, NGA Office of Corporate CommunicationsMap image provided by the Missouri History Museum.

Graphic by Beth Neise, NGA Office of Corporate Communications

Ninety years later, a look at an NGA predecessor organization’s contributions to the first solo transatlantic flight

Ninety years ago this May, Charles Lindbergh landed a single-engine monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, at Le Bourget airport northeast of Paris among more than 25,000 cheering spectators. Lindbergh emerged as the first pilot to complete a solo, transatlantic flight and the first pilot to fly nonstop from North America to mainland Europe.

Lindbergh’s flight made him an international sensation, popularized the concept of air travel and showed the world the potential of aviation.

And as Lindbergh landed in France, tucked away in his cockpit was the chart he used to navigate from New York to Paris — a chart made by the U.S. Hydrographic Office, an NGA predecessor agency.

Before Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, the public perception of aviation was that of a risky, expensive novelty. Lindbergh, a former U.S. Army pilot, wanted his flight to Paris to change that.

“Businessmen think of aviation in terms of barnstorming, flying circuses, crashes and high costs per flying hour,” Lindbergh wrote in his book, The Spirit of St. Louis.

“Somehow they must be made to understand the possibilities of flight.”

Skeptics told Lindbergh that a solo trip across the Atlantic on a single-engine plane would be hazardous, if not suicidal.

Airplane companies dismissed the idea of an unknown airmail pilot from St. Louis achieving what no one had before.

But Lindbergh rallied support from the fledgling aviation community in St. Louis for his idea and raised money from local businessmen to purchase a plane custom-built for the trip, named the Spirit of St. Louis.

But could he find his way from New York to Paris?

Until his famous flight, Lindbergh had navigated only across land, not large bodies of water.

He had used landmarks on the ground — rivers, towns, lakes, railroad tracks — to help him determine where he was, Lindbergh wrote in his book.

To fly the Atlantic, Lindbergh decided he would have to navigate like a ship captain at sea.

To do that, he would need a set of charts that covered the Atlantic Ocean.

Lindbergh was in California at the time, with the engineers building his plane.

In a store in San Pedro, Lindbergh found exactly what he needed.

“The salesman pulls out two oblong sheets,” he wrote in The Spirit of St. Louis.

“They’re Mercator’s projections, and — yes, I’m in luck — they extend inland far enough to include New York and Paris.”

A Mercator’s projection is a map in which the meridians and the parallels of latitude are straight lines, intersecting each other at right angles.

Because of the spherical shape of the Earth, distortion increases as distance from the equator increases.

At least one, and likely both, of those charts were created by the Hydrographic Office.

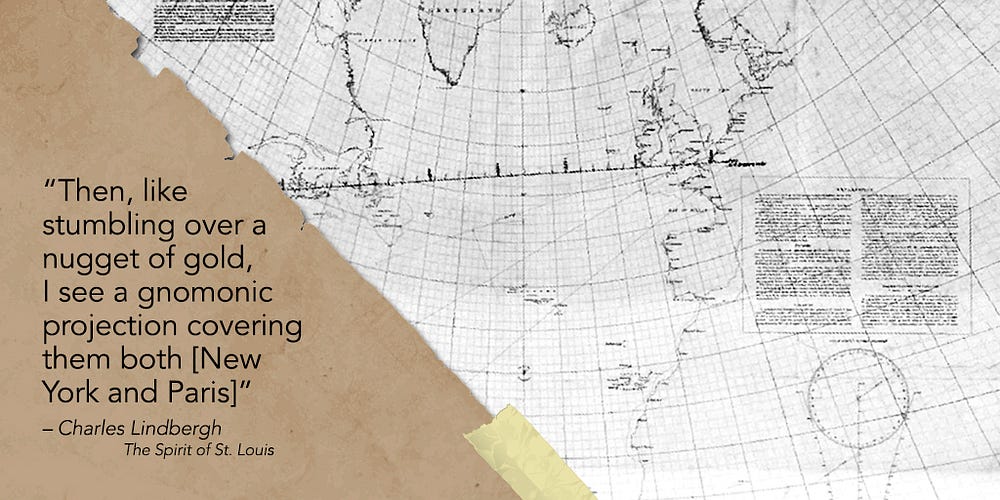

“Then, like stumbling over a nugget of gold, I see a gnomonic projection covering them both [New York and Paris],” he wrote.

This gnomonic projection, also created by the Hydrographic Office, showed a projection of the Atlantic in which the eye is imagined to be at the center of the Earth sphere.

Lindbergh recalled his military training and knew he would need both charts to accurately navigate from New York to Paris.

“‘A great circle on the Earth’s surface translates into a curve on a Mercator’s chart, but it becomes a straight line on a gnomonic projection’ — I remember learning that in the Army’s navigation class,” he wrote.

“Why? Because all maps are distorted in one way or another. You can’t just skim the surface off a globe and flatten it out neatly on a table.”

see UWM Library

Lindbergh chart Variations of the compass for the year 1925

se UWM Library

Maps from the U.S. Hydrographic Office, an NGA predecessor organization,

consulted by Charles Lindbergh during the planning of the first solo

transatlantic flight.

Images courtesy of American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin — Milwaukee Libraries

In addition to the gnomonic and Mercator projections of the Atlantic, Lindbergh also purchased a chart for magnetic variation and a time-zone chart, both also created by the Hydrographic Office, and some others showing the prevailing winds across the Atlantic during the spring.

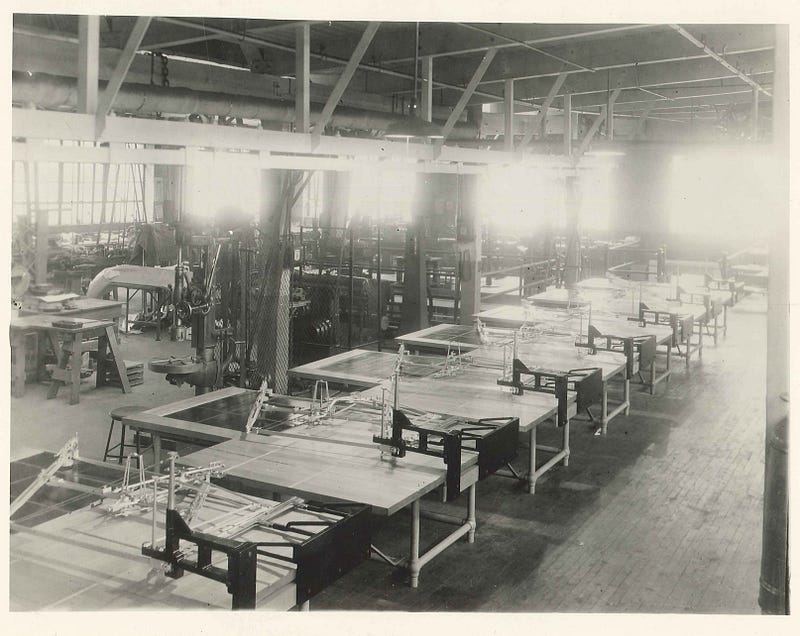

An undated photo of the U.S. Hydrographic Office.

Image courtesy of NGA’s Historical Research Center.

The Hydrographic Office began in 1830 as the Depot for Charts and Instruments.

It was the first U.S. government entity to take responsibility for the mapping of oceans, lakes and rivers, or hydrographic charting.

Pilot Chart of

the North Atlantic Ocean.

June 1923 issue of the monthly aid to marine

navigation published by the U.S. Hydrographic Office.

In 1842, the office began to implement an extensive system for collecting hydrographic information — ocean currents, winds, air pressure and temperature, water temperature and more — from mariners. It used this information to create accurate charts with exactly the information mariners most needed.

The program was so successful that the Hydrographic Office earned an international reputation for excellence in charting, wrote Mitchell Kalloch in A Concise History of the U.S. Hydrographic Office.

Lindbergh brought his Hydrographic Office charts back to the factory where his airplane was being built.

He settled into a drafting room and went to work.

“It’s a dusty, uninspiring place, with damp-spotted walls and [an] unshaded light bulb hanging down on a wire cord from the ceiling’s center,” he wrote.

“But there’s enough room to spread out sheets of charts and drawings.”

from slides

In his book, Lindbergh described how he charted his course: On the gnomonic projection, he drew a straight line between New York and Paris.

Then he transferred points from that line, at 100-mile intervals, to the Mercator’s projection, and connected those points with straight lines to create a curved course, connecting the two cities.

At each point, Lindbergh marked the distance from New York and determined how to adjust his course to remain on his route and account for the magnetic variations he would find as he traveled across the Atlantic.

Lindbergh’s straight-line route on a gnomic projection became curved

when translated to a Mercator projection.

Lindbergh cut out the relevant

strips from his Mercator projections and used them to navigate to

Paris.

Finished with his course, Lindbergh admired the arc he had created.

“It’s fascinating, that curving, polygonic line, cutting fearlessly over thousands of miles of continent and ocean,” Lindbergh wrote. “It curves gracefully northward through New England, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, eastward over the Atlantic, down past the southern tip of Ireland, across a narrow strip of England, until at last it ends sharply at the little dot inside France marked ‘Paris’.”

Lindbergh decided to chart the route again using trigonometry, just to double-check his work.

After teaching himself the math from library books and spending several days performing calculations, Lindbergh was satisfied: His course was correct.

Map image courtesy of the Missouri History Museum.

Graphic by Beth Neise, NGA Office of Corporate Communications

With him, he carried his arc, sketched on the Hydrographic Office Mercator’s projection between the continents.

A couple hours later, as he flew over Massachusetts and started over the Atlantic, he pulled out his route and checked his compass.

“This strip is my key to Europe,” he wrote in his book.

“With it, I can fly the ocean. … Without this strip, it would be as useless to look for Paris as to hunt for buried treasure without a pirate’s chart.”

After flying over Newfoundland, Lindbergh spent about 16 bleary hours over the Atlantic.

Then he spotted land on his horizon: the southwestern coast of Ireland!

At 10:22 p.m. French time, 33 ½ hours after taking off from New York, Lindbergh landed in Paris.

He had traveled 5,790 kilometers, nonstop, alone, in a little over a day, with a chart and a compass.

The significance of the successful flight was recognized immediately.

The exhausted Lindbergh emerged from his plane to face an effusive, nearly hysterical crowd.

He hadn’t slept for more than 63 hours.

“Twenty hands reached for him and lifted him out like he was a baby,” wrote Edwin James that day for The New York Times.

“He had strength enough, however, to smile and waved his hand to the crowd.”

Two French pilots quickly whisked Lindbergh away as the crowd surged.

Onlookers tore off pieces of his Spirit of St. Louis plane as souvenirs.

Newspaper reporters gathered at the U.S. Embassy, waiting for Lindbergh to arrive.

A painting by former employee shows the Spirit of St. Louis flying close

to the water on its trip across the Atlantic.

It was painted in the

1970s to decorate the agency’s Lindbergh dining room, which is now part

of the Building 1 Conference Center at NGA’s St. Louis campus.

The

painting currently hangs in NGA’s St. Louis museum.

Fortunately, among the chaos, Lindbergh’s Hydrographic Office charts survived.

Lindbergh donated the charts he used during the flight to the Missouri History Museum.

He donated the charts he used to plan the fight — the gnomonic, magnetic variation and time-zone maps — to the American Geographical Society, and they are now housed at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

The United States eventually folded the Hydrographic Department into the Defense Mapping Agency in 1972.

In 1978, the agency merged the Hydrographic Center with the Topographic Center, creating the Defense Mapping Agency Hydrographic/Topographic Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

In 1996, it became part of the National Imagery and Mapping Agency, which became NGA in 2003.

Despite the name changes, NGA employees continue the legacy of the Hydrographic Office even today.

NGA analysts, scientists and cartographers still deliver information that American airmen use to navigate safely.

NGA provides digital data used in navigation equipment in airplane cockpits and in mobile devices.

Map showing the overland and overseas flights of Charles A. Lindbergh, Colonel and flight comdr 110th observation Sqdn. Missouri Nat. Guard (1928)

courtesy of Univ. Hawaii

They also still create hard-copy paper maps, similar to the ones consulted by Lindbergh to achieve the transatlantic flight once thought impossible.

“I can hardly believe it’s true,” he wrote.

“I’m almost exactly on my route, closer than I hoped to come in my wildest dreams.”

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment