From Gizmodo by Maddie Stone

In October 2012, just a few days before Hurricane Sandy slammed into New Jersey, it was churning north past the narrow strip of white sand beach separating NASA’s most celebrated spaceport from the sea.

For several days and nights, heavy storm surge pounded the shoreline, flattening dunes and blowing sand right up to the launchpads.

A stone’s throw away from the spot where a Saturn V rocket sent the first humans to the Moon, the ocean took a 100-foot bite out of the beach.

“I think the telling story is that the storm was almost 230 miles offshore, and it still had an impact,” Don Dankert, an environmental scientist at NASA, tells me as we stand with ecologist Carlton Hall atop a rickety metal security tower overlooking Space Coast.

It is a hot, breathless day, and the surf laps gently at the deserted shore.

“It makes you wonder what would happen if a storm like that came in much closer, or collided with the coast,” Dankert adds.

Space Coast with the GeoGarage platform (NOAA chart)

That’s a troubling question for NASA, an agency whose most valuable piece of real estate—the $10.9 billion sandbar called Kennedy Space Center—is also its most threatened.

The beating heart of American spaceflight since the Apollo program, Kennedy was, and still is, the only place on US soil where humans can launch into orbit.

Today, the center is enjoying a revival, following a few dark years after the space shuttle program was mothballed and crewed launches were outsourced to Russia.

The shuttle’s former digs, Launch Pad 39A, is being renovated by commercial spaceflight company SpaceX for the Falcon Heavy, a beast of a rocket designed to ferry astronauts into orbit and beyond.

A few miles up the road, Launch Pad 39B is being modified for the SLS rocket, which NASA hopes will send the first humans to Mars.

But a glorious future of bigger and badder rockets is by no means assured. In fact, that future is gravely threatened, not by the budget cuts that NASA speaks speaks often and candidly about, but by climate change.

If humans keep putting carbon in the atmosphere, eventually, Kennedy won’t be sending anybody into space.

It’ll be underwater.

Aerial view of Kennedy Space Center’s two Launch Pads, 39A and 39B,

along with the Launch Control Center, which includes the Vehicle

Assembly Building. Launch Pad 41b is located at Cape Canaveral Air Force

Station.

Image: Josh Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory/USGS

“We are acutely aware that, in the long-term sense, the viability of our presence at Space Coast is in question,” says Kim Toufectis, a facilities planner in NASA’s Office of Strategic Infrastructure.

There’s a very good reason NASA built Kennedy Space Center, along with four other launch and research facilities, on the edge of the sea. If rockets are going to explode (and in 2016, they still do), we’d rather them explode over water than over people. “To launch to space safely, you have to be at the coast,” says Caroline Massey, assistant director for management operations at Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia.

Kennedy’s location, at the southern end of the Merritt Island wildlife refuge and just northwest of Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, has a few other perks.

Launch pads and other resources are shared with the Air Force, and weather conditions are good year-round.

Being close to the equator allows rockets to snag a bigger velocity boost from the rotation of the Earth.

And yet, even as architects were drawing up plans for Kennedy in the early 1960s, NASA knew the spaceport’s exposure—to rising sea levels, hurricanes, and the general wear and tear of the ocean—might one day cause catastrophic damage.

“They were absolutely concerned about it,” says Roger Launius, associate director at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and former chief historian for NASA.

“But they wanted to launch over water. You don’t want to drop first stages over cities.”

Aerial view of Kennedy Space Center’s shoreline before any launchpads

were installed, left (1943) and in modern history (2007).

Photos

Courtesy John Jaeger.

Globally, sea levels have gone up about eight inches since the early 1900s.

For the past two decades, the pace of rise has been quickening, in step with accelerated melting on the Greenland ice sheet.

At Kennedy, conservative climate models project 5 to 8 inches of sea level rise by mid-century, and up to 15 inches by the 2080s.

Models that take changing ice sheet dynamics into account predict as much as fifty inches (4.2 feet) of rise by the 2080s.

In an even more dire scenario, Space Coast sees over six feet of rise by the end of the century, causing many of the roads and launchpads, not to mention sewers and buried electrical infrastructure, to become swamped.

“I hope we don’t go there,” Hall said.

On top of rising seas, Kennedy faces a stormier future—more extreme hurricanes in the summer and nor’easters in the winter.

“We started to notice a real issue with coastal erosion following the 2004 hurricanes,” says John Jaeger, a coastal geologist at the University of Florida.

Jaeger is part of a team of scientists who’ve been studying long-term shoreline recession at Space Coast, which can be traced back to the 1940s through aerial photographs.

But while natural erosion has been reshaping Kennedy’s sandy fringes for decades, a recent uptick in powerful storms has Jaeger worried for the future.

“As geologists, we know it’s these big events that do all the work,” he says.

NASA’s Climate Adaptation Sciences Investigators Workgroup (CASI) shares this concern.

In a recent review of the space agency’s climate vulnerability, this team of in-house Earth scientists and facilities managers cited extreme weather and flooding as major hazards to future operations at Kennedy.

Even under modest sea level rise scenarios, ten-year flood events are expected to occur two to three times as often by mid-century.

And the more the ocean rises, the easier it’ll be for storms to cause flooding.

“I use the metaphor that a small change in the average can lead to a big change in extremes,” says Ben Strauss, vice president for sea level rise and climate impacts at Climate Central.

“In basketball, it’s pretty hard to get a slam dunk, but if you raised the floor a foot, they would happen all the time.”

In other words, the coastal damage caused by Sandy may be a small taste of what Kennedy Space Center is in for.

After soaking in the view for a few moments, Dankert, Hall and I climb down from the watchtower and drive south to Kennedy’s dune restoration site, which was completed in 2014 with federal Hurricane Sandy relief funds.

Stretching a little over a mile between Launch Complexes 39A and 39B, the dune’s grassy slopes rise like lightly yeasted bread over the sprawling beach.

If you didn’t know better, you might think the shoreline had looked this way for centuries.

View along the beach of Kennedy Space Center’s dune restoration site in 2014.

Photo Courtesy Dan Casper/NASA.

“We’re drawing a line in the sand,” Dankert says.

“The dune not only prevents storm surge from plowing inland, it’s a sand source that replenishes the beach.”

It’s an astonishingly low-tech barrier when you consider the artificial pumping systems installed at Miami Beach to keep the ocean at bay, or the enormous seawalls some experts think we’ll need to save Manhattan.

But in protecting its shoreline, NASA is trying to be considerate of all of its residents.

In addition to rockets, Kennedy is home to a stunning array of wildlife, from bobcats and coyotes to southeastern beach mice, scrub jays, and gopher tortoises.

It’s a major nesting site for protected leatherback, green, and loggerhead sea turtles, with thousands of baby turtles born on this small stretch of beach each year.

“We are a wildlife refuge—that is a huge part of our program,” Dankert says, adding that in addition to maintaining the shoreline, Kennedy’s newly-restored dune blocks artificial light from the launch pads, which can disorient female sea turtles as they’re coming ashore to nest.

For the past few years, the dune has held strong, preventing the ocean from spilling over onto the historic shuttle railroad that traces along the coast.

Eventually, NASA would like to put in another two miles of dune, fortifying the entire shoreline between Launch Complexes 39A and 39B.

As with all government projects, the hang-up is funding.

The post-Sandy dune reconstruction was completed for a cool $3 million, using beach-quality sand trucked up from Cape Canaveral.

“We got really lucky—that sand was a big cost-saver,” Hall says, noting that the bill might have run in the tens of millions had NASA been forced to dredge sand from offshore.

An Atlas V rocket lifts off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station’s

Launch Complex 41, illumining nearby Kennedy Space Center’s dune

restoration site.

Photo Courtesy Tony Gray/NASA.

“To rebuild a pad is a few billion dollars,” Hall says.

“To spend a few million every few years instead is a pretty good investment.”

Although Kennedy is NASA’s most threatened asset, all of the space agency’s properties—some $32 billion worth of infrastructure used for scientific research, aeronautics testing, astronaut training, deep space missions, and vehicle assembly—face challenges in a changing climate.

Sea levels at the Johnson Research Center in Texas are rising at a whopping 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) per decade, faster than any other coastal center by a factor of two or three.

The Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans sits below sea level, surrounded by 19 foot-high levees, on rapidly-sinking ground. Inland facilities are bracing for more excessively hot days, and the Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley is preparing for a future of drought.

“This is a very large concern for our agency as a whole,” Toufectis says.

And given our growing need to go into space, not just for scientific research, but to harness new resources, colonize other worlds, and monitor and study the one overburdened biosphere we’ve got, anything that threatens future operations and NASA threatens the entire nation.

At Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s eastern shore, climate change isn’t some existential problem for the future—it’s reality.

The center’s sounding rocket launch pads, which have sent countless aircraft models and science experiments into suborbital space, sit on a six square-mile barrier island just a few hundred feet from the ocean, alongside two Virginia-owned pads used for satellite launches and ISS resupply runs.

Sea levels are rising, storms are getting fiercer, and protective beaches are eroding rapidly.

“We live with climate change every day,” Massey says.

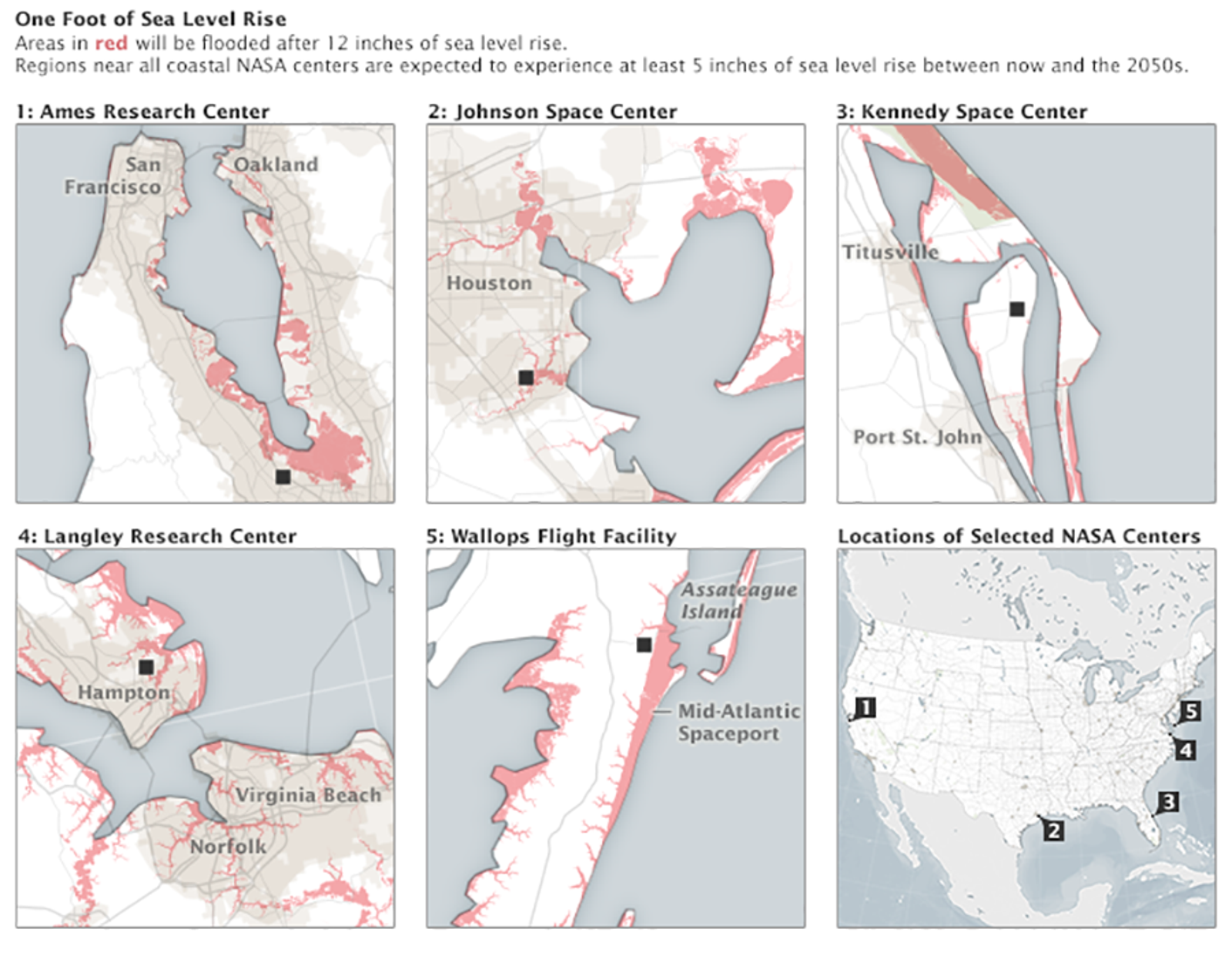

Areas around five coastal NASA centers that would be inundated by 12

inches (30 cm) of sea level rise (red).

Image: Josh Stevens/NASA Earth

Observatory

But while the wall initially helped to reduce storm damage, the beach beyond it was soon worn to shreds.

By the mid 2000s, storm waves were breaking directly against the wall, causing sections to crumble into the sea.

And so, in the spring of 2012 and the summer of 2014, with a $54 million investment from Congress, NASA and the US Army Corps of Engineers dredged almost 4 million cubic yards of sand from offshore, and a new beach was built beyond the wall.

The impact was sudden and dramatic.

“When Hurricane Irene hit in 2011, Wallops [Island] was flooded, we had $3.8 million in storm damage, and we couldn’t work there for a few weeks,” Massey says.

But when Sandy, virtually the same strength as Irene, blew past Virginia’s coastline a year later?

“There was no island flooding to speak of, and we could have kept the power on the entire time,” Massey says.

“The only difference was our shoreline protection program.”

At Wallops as at Kennedy, shoring up the shoreline every few years is considered an economical way to manage the risk right now.

But looking out toward the late 21st century and beyond, NASA may be forced to leave some of these launchpads behind.

“In the long-term, I would be shocked if we don’t see more than six feet of sea level rise,” Strauss says.

“That amount may simply be incompatible with a lot of NASA’s coastal infrastructure.”

Picking up and moving inland, or “managed retreat” in the urban planning parlance, is the last thing the space agency wants to do.

Ironically, it probably won’t be a major storm or flood that forces NASA’s hand.

It’ll be its employees.

You can’t have rocket launches on Space Coast if you can’t find engineers, mission directors and launch personnel willing to run them—which is to say, people willing to live and work in an increasingly hostile environment.

“The point at which we get serious about moving is the point at which the community is no longer viable,” Toufectis said.

Full-scale withdrawal at any of NASA’s centers is probably decades away.

But at Wallops, the seeds of a managed retreat mentality are already starting to sink in.

There’s now an intensive screening process for what can be built on the island: “It has to be something we can only do safely over water,” says Josh Bundick, program manager for management operations at Wallops.

Island operations are run by a skeleton crew, while the vast majority of Wallops employees work at the facility’s main base a few miles inland.

NASA hasn’t broken off its relationship with Wallops Island, but it is creating distance.

As I head back to Kennedy’s visitor center, ogling the tremendous Vehicle Assembly Building where the Saturn V rocket was put together, I can’t help but feel a strange sense of cognitive dissonance.

Here I am, at a place that radiates optimism, that flaunts the raw power of human technology that was built to explore the infinite, only to learn of man’s essential helplessness in the face of nature.

The sense of two parallel realities grows stronger as I return to my hotel in Titusville, where gaggles of tourists take selfies with replica astronaut suits and locals share beers over the latest SpaceX gossip.

This isn’t a community with any intention of going anywhere.

But no matter what the future holds for Space Coast, one thing is clear: defending this shoreline now isn’t a waste.

Places on the front lines of climate change have lessons to teach us about standing one’s ground, and deciding when the ground can no longer stand.

And those lessons may wind up being more valuable than a hundred launchpads.

“But that doesn’t stop us from leading meaningful lives. I could tell you that the barrier islands on the Atlantic coast may not survive this century and almost certainly won’t survive the next, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make good use of them now. We just have to keep our eyes open.”

Links :

- Military : Key Navy Base at Risk from Rising Seas: Mabus

- Musings on Maps blog : We Think Our Shores Are Stable,–but Need to Know that They Are Not

No comments:

Post a Comment