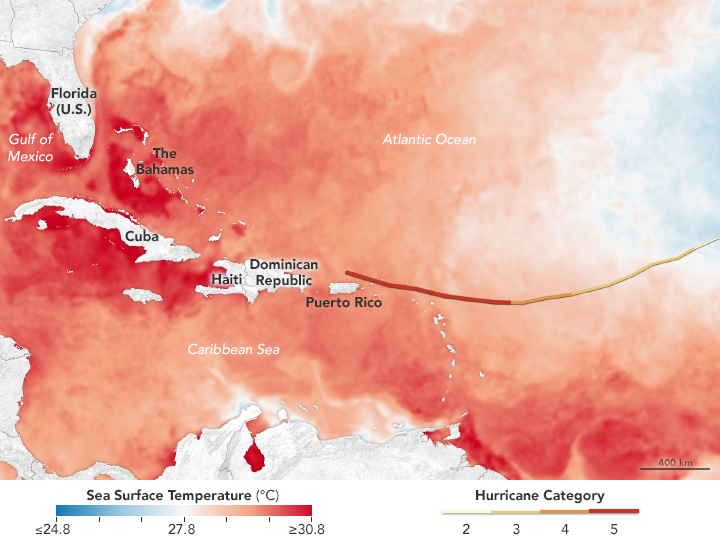

The map above shows sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean,

Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico on September 5, 2017.

The data were

compiled by Coral Reef Watch,

which blends observations from the Suomi NPP, MTSAT, Meteosat, and GOES

satellites and computer models.

The mid-point of the color scale is

27.8°C, a threshold that scientists generally believe to be warm enough

to fuel a hurricane.

The yellow-to-red line on the map represents Irma’s

track from September 3–6.

From New Scientist by Michael Le Page

It’s a monster.

As the eye of Hurricane Irma approached the tiny island of Barbuda this morning, wind speeds soared to 250 kph before the instrument broke.

On September 6, 2017, Hurricane Irma slammed into the Leeward Islands on

its way toward Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the U.S. mainland.

As the

category 5 storm approaches the Bahamas and Florida in the coming days,

it will be passing over waters that are warmer than 30 degrees Celsius

(86 degrees Fahrenheit)—hot enough to sustain a category 5 storm.

Warm

oceans, along with low wind shear, are two key ingredients that fuel and

sustain hurricanes.

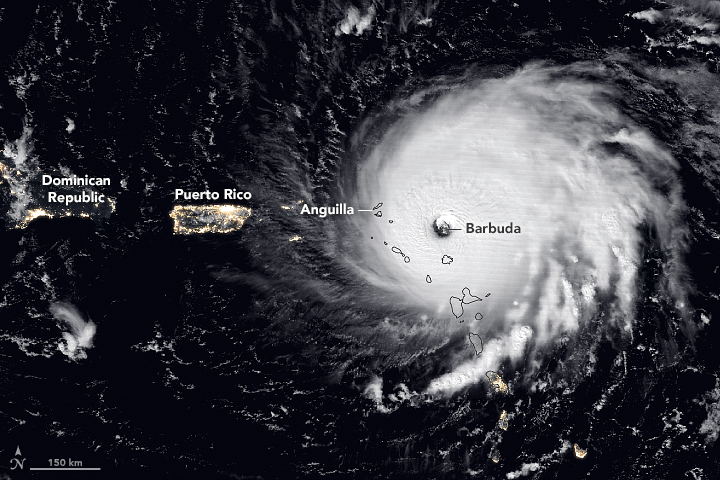

The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite captured a nighttime view of the storm at 1:35 a.m. local time (05:35 Universal Time) on September 6 as the eye was over the island of Barbuda.

The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite captured a nighttime view of the storm at 1:35 a.m. local time (05:35 Universal Time) on September 6 as the eye was over the island of Barbuda.

The image was acquired by the VIIRS “day-night band,”

which detects light in a range of wavelengths from green to

near-infrared and uses filtering techniques to observe signals such as

city lights, auroras, wildfires, and reflected moonlight.

In this case,

the clouds were lit by the full Moon.

The image is a composite, showing

storm imagery combined with VIIRS imagery of city lights.

But already reports of severe destruction are coming in from other islands in Irma’s path.

The destruction could be extreme.

Hurricane Irma has the strongest winds of any hurricane to form in the open Atlantic, with sustained wind speeds of 295 kph.

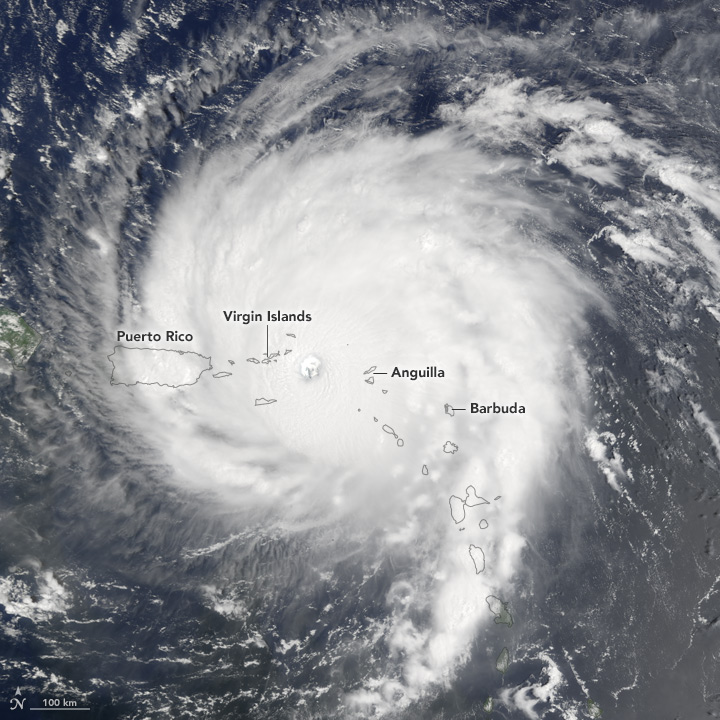

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer

(MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired the third image at 10:35

a.m. local time (14:35 Universal Time) on September 6, 2017.

By then,

the storm had also hit Anguilla and was poised to strike the Virgin

Islands.

The strongest winds are limited to a relatively small area around its centre, but hurricane-force winds of 118 kph or more extend out 85 kilometres from its eye.

Irma could yet grow stronger and is going to graze or directly hit many densely-populated islands in the Caribbean before possibly making landfall in Florida on Sunday – but there is still a lot of uncertainty about its path and intensity this far ahead.

NASA SPoRT Sea Surface Temperature product shows warm water along projected path of Hurricane Irma, favorable for maintaining strength.

Warmer waters

So why did Irma grow so strong?

Most likely because climate change is making Atlantic waters ever warmer.

Tropical cyclones are fuelled by warm surface waters of around 26°C or more.

They draw in moist air from all around them, and as it rises, the water vapour condenses out and releases latent heat, which drives further uplift. Irma’s clouds are 20 kilometres high.

However, as tropical cyclones grow stronger they churn up the ocean and bring deeper water to the surface.

Usually this deeper water is cooler, and cuts off the energy supply.

The strongest hurricanes, then, can only grow if warm waters extend down to depth of 50 or 100 metres – conditions normally only found in the Gulf or Caribbean.

In 1990, Hurricane Allen reached 305 kph winds, fuelled by these warmer waters.

In 2017’s warmer world, Irma began growing way out in the Atlantic, thanks to sea surface temperatures that were more than 1°C above average.

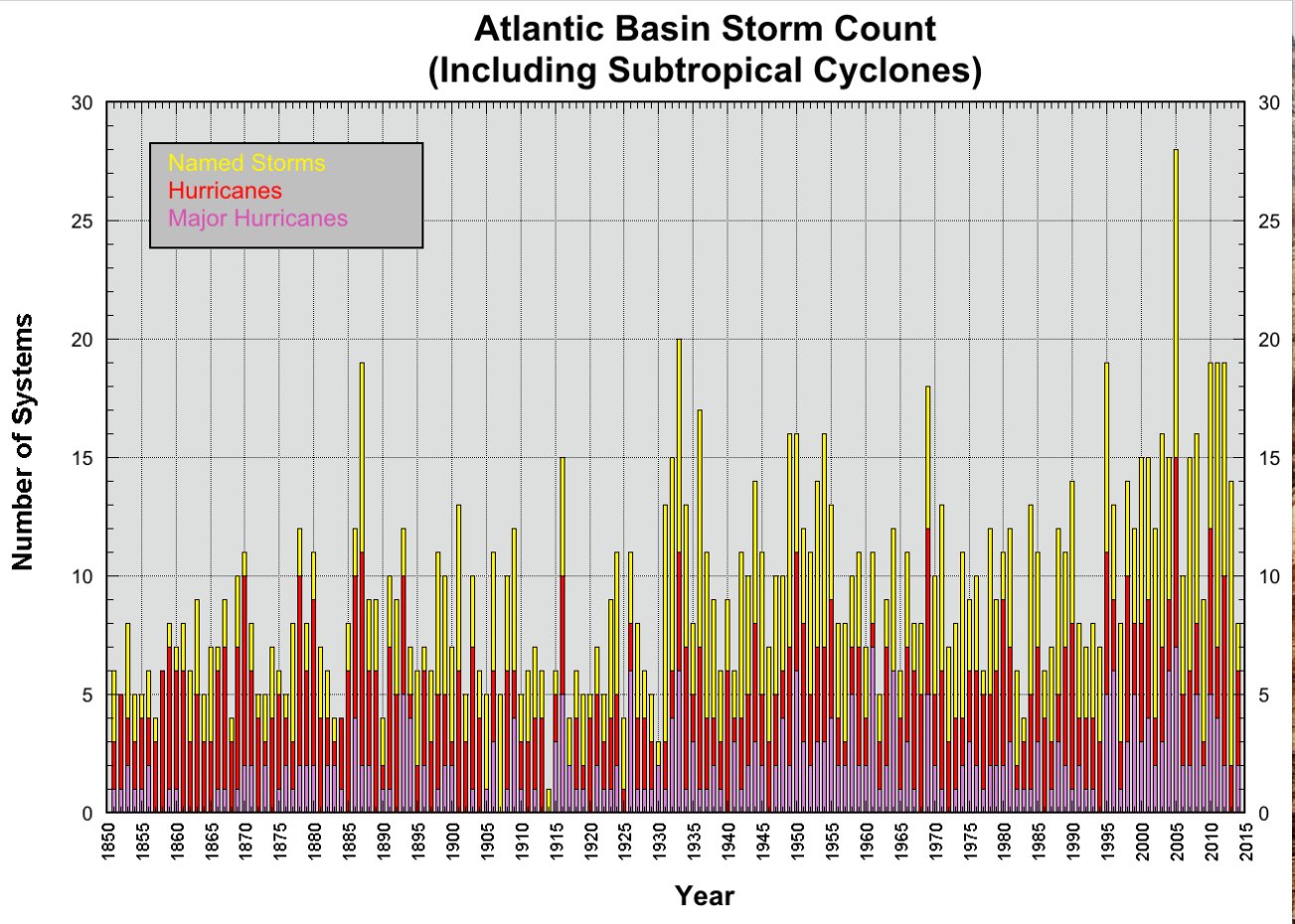

Bars depict number of named systems (yellow), hurricanes (red), and category 3 or greater (purple), 1850-2014

Stronger storms

Hurricane intensity depends on many other factors, too, though.

For instance, winds high in the atmosphere are often faster than those lower down, blowing away rising air and preventing hurricanes from forming, or growing very strong.

Low wind shear helped Irma grow into a perfect storm.

Computer models suggest global warming is likely to increase wind shear over the Atlantic, meaning there could no more or fewer hurricanes overall, but that storms grow stronger when they do form.

While tropical cyclones are currently ranked according to their wind speed, storm surges and flooding from high rainfall typically cause most of the damage, as we saw with Harvey.

The height of a storm surge depends not just on the strength of winds, but on their extent.

Hurricane Sandy’s winds were not that strong but the size of the storm piled up the huge storm surge that caused most of the damage in New York and elsewhere.

So strong winds don’t necessarily mean big damage.

The record is held by Hurricane Patricia in the eastern Pacific in 2015, with sustained winds of 345 kph.

Fortunately Patricia was small, weakened dramatically before landfall and struck a sparsely populated area.

Irma, ominously, is both big and intense, and could cause big storm surges in highly populated places. Barbuda recorded a storm surge of 2.4 metres.

The amount of rainfall dumped by hurricanes can also vary widely depending both on a storm’s intensity, local factor and how fast it moves.

Harvey produced huge amounts of rain because it barely moved for days.

Irma, thankfully, is moving faster – but its behaviour more than two or three days ahead remains highly uncertain.

Links :

- NASA : Hot Water Ahead for Hurricane Irma

- Climate Central : Warmer Air Means More Evaporation and Precipitation

Washington Post :

ReplyDeleteIrma and Harvey should kill any doubt that climate change is real